(c) National Media Museum

Ever since technology has allowed people to capture pictures, photographers have been using photo-editing techniques to trick people. One of the most fascinating early examples is spirit photography.

William Hope (c) National Media Museum

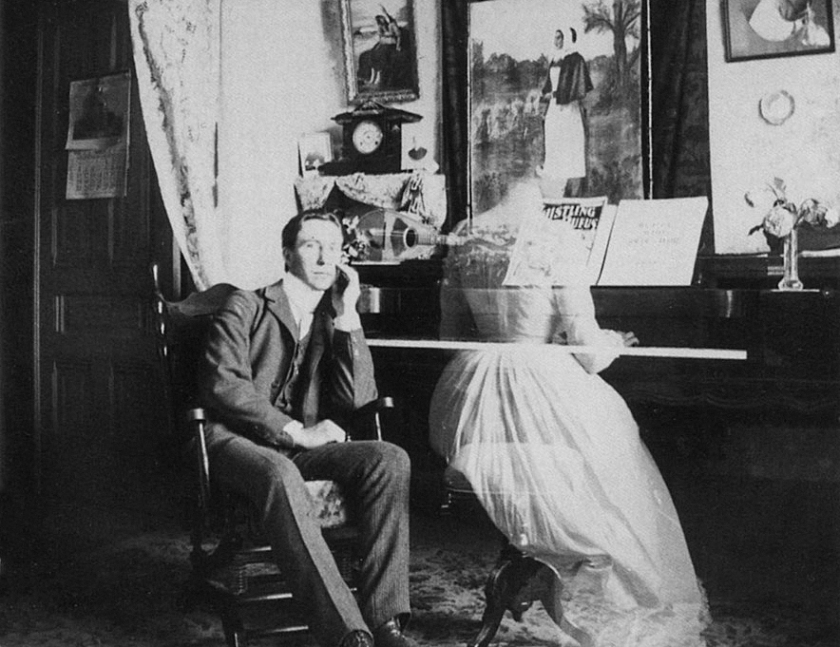

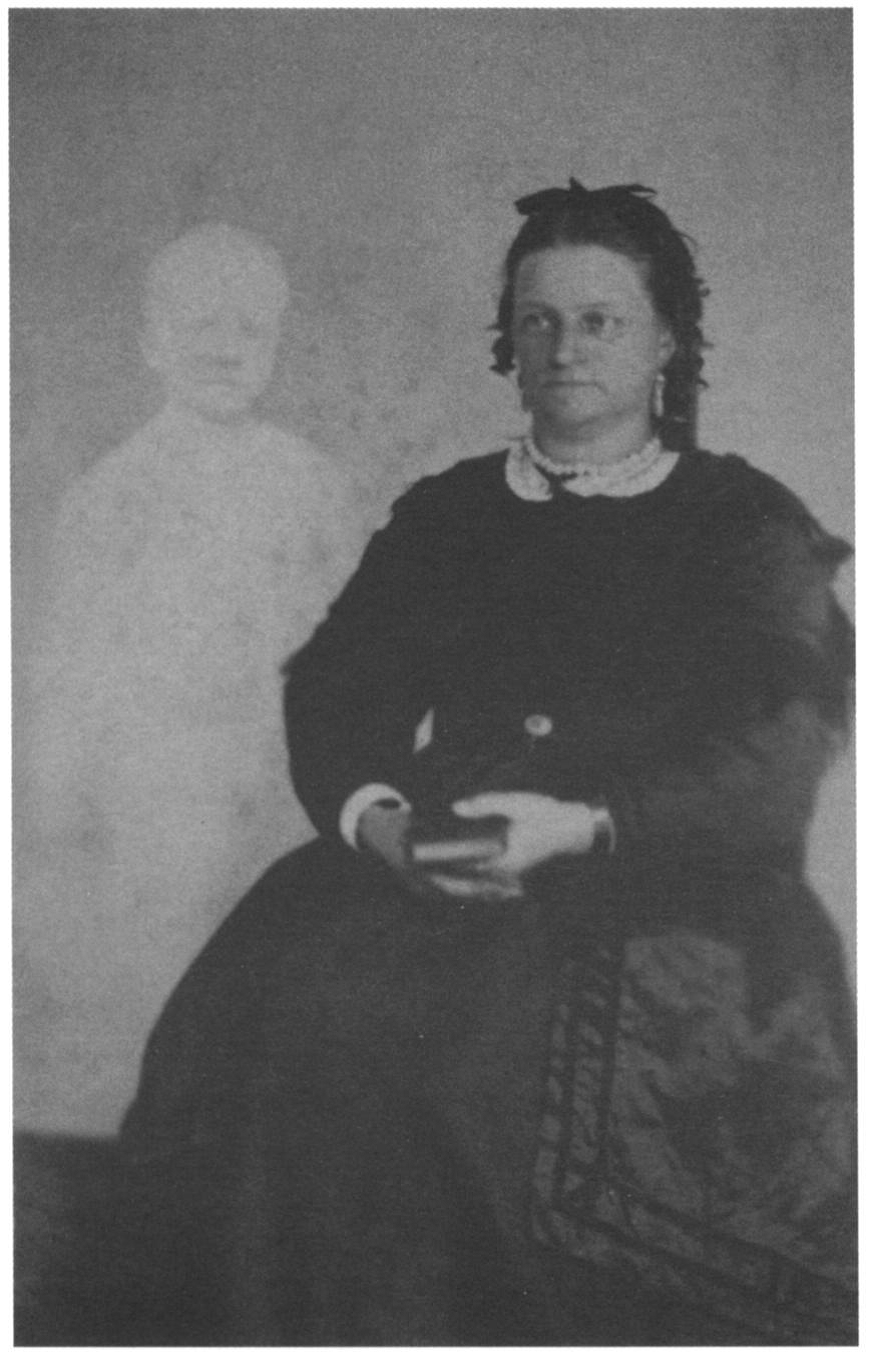

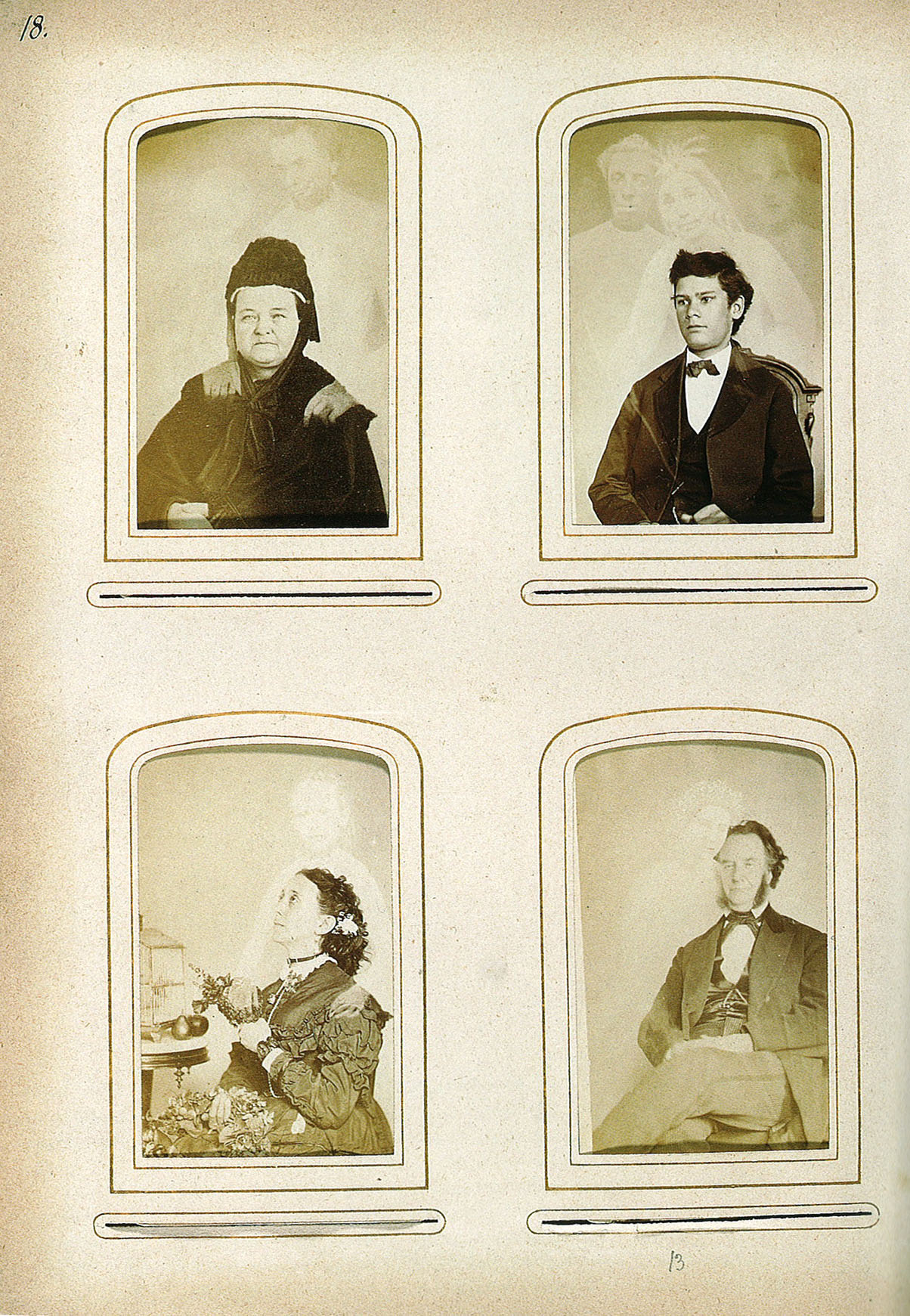

Spirit photography was a trend in which a photographer edited pictures to make ghosts or spirit-like figures appear alongside the human subjects. These pictures were often made using a double exposure technique, where one exposure is layered on top of another. Customers believed that the spirits of lost loved ones were communicating with them through these photographs.

Photograph by William Hope (c) National Media Museum

Communicating with the dead was important to Victorians because it seemed like death was all around them. In America, many lost people in the Civil War, and in other countries, mortality rates were generally high. Diseases such as tuberculosis spread, and life for the growing urban working class was harsh in the pre-sanitary revolution era. The mid-to-late 1800s were also a time of rapid industrialization and progress, so connecting with the dead allowed people to feel tied to the past, and new religious movements incorporated spiritualism.

An image of ‘Mrs French’ with a ghost circa 1868 by William H. Mumler

The first spirit photographer was William Mumler, who discovered a double exposure technique in the 1860s that made ghostlike figures appear in photographs. Mumler was a jewelry engraver and amateur photographer who was developing a self-portrait when he noticed an apparition that was supposedly his cousin who had died 12 years earlier.

Becoming a full-time spirit photographer, Mumler conducted his business alongside his wife, a well-known healing medium. He would take pictures of people and then alter the negatives using other pictures to make “spirits” appear with the living subjects.

Becoming a full-time spirit photographer, Mumler conducted his business alongside his wife, a well-known healing medium. He would take pictures of people and then alter the negatives using other pictures to make “spirits” appear with the living subjects.

Mumler (pictured above in a self-portrait with the “ghost of his cousin”) was eventually exposed as a fraud after living residents of Boston were identified as “spirits” in his pictures.

He was also accused of breaking into people’s houses to steal photos of the deceased to put into the pictures.

In 1869, Mumler was tried for fraud. One critic who testified against him was circus founder (and hoax promoter) P.T. Barnum, who argued that Mumler was taking advantage of people whose judgment was clouded by grief. In the end, there wasn’t enough evidence to convict Mumler, however, his career was ruined in the aftermath of the scandal.

Mumler’s most famous picture shows Mary Todd Lincoln with what is supposed to be the ghost of her deceased husband, Abraham Lincoln (top left). There are two different accounts of how the image came to be. According to one, Mary Todd Lincoln was using the pseudonym “Mrs. Tundall” when she had her picture taken, and Mumler did not figure out who she was until after the picture was developed. In another, the picture was taken in the early 1870s with Mrs. Lincoln using the name “Mrs. Lindall,” and Mumler’s wife encouraged her to identify her husband’s figure in the photo. It continues to be circulated despite being recognized as a fake.

via

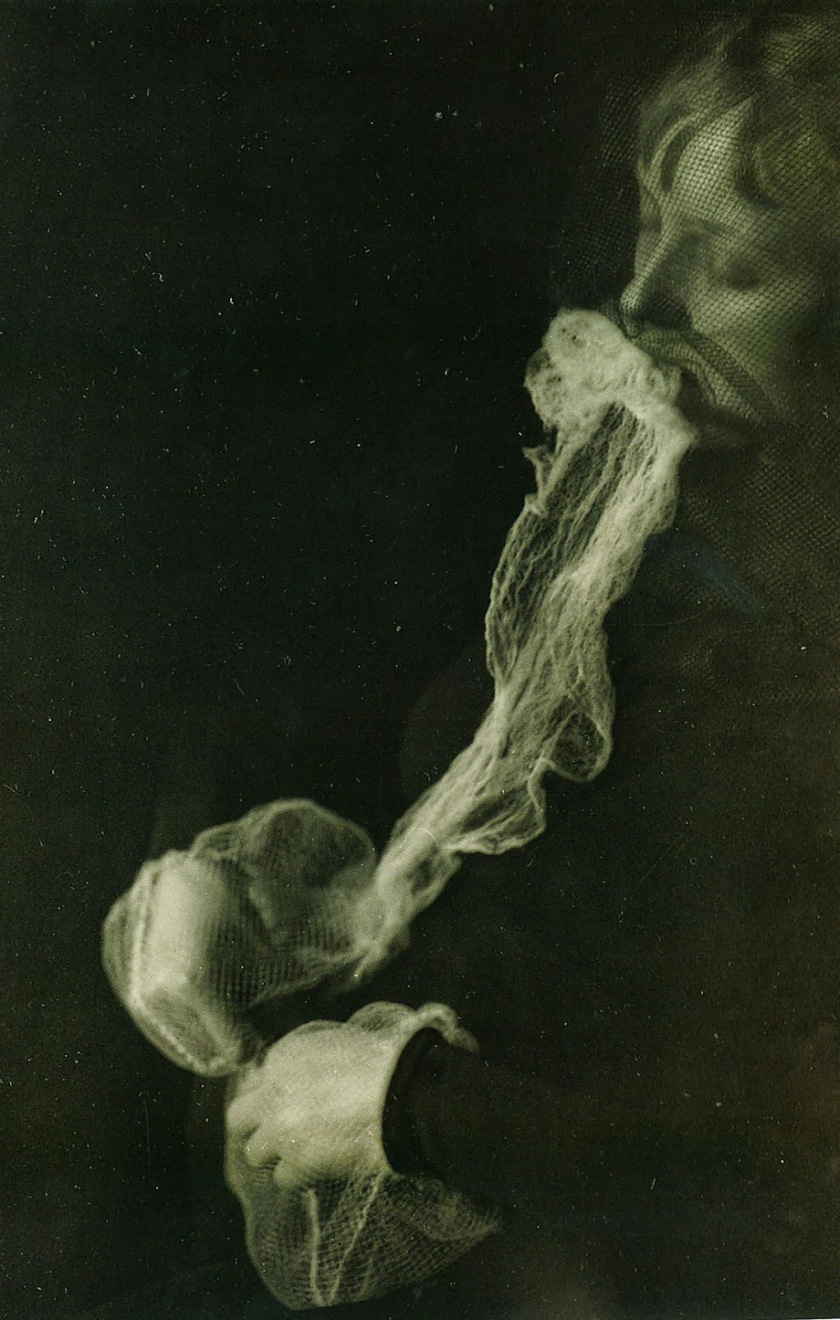

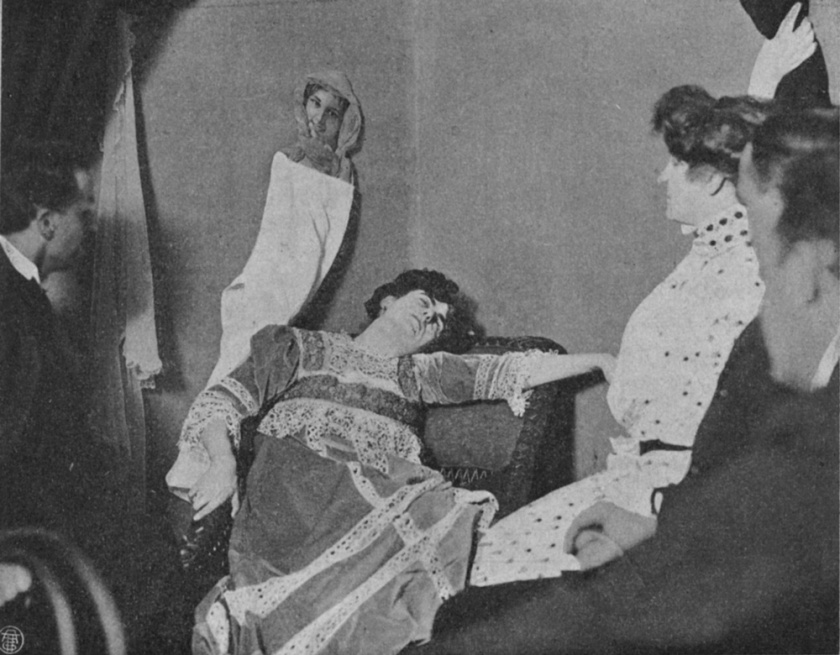

By the 1870s, spirit photography spread to Europe, where it took on an even more disturbing shape. Spirit photography was being endorsed by spiritual mediums, but also by some of society’s prominent scientists. Some claimed that spirits could take form through a substance called ectoplasm, a term that was coined by a Nobel prize-winning scientist no less, French physiologist, Charles Richet.

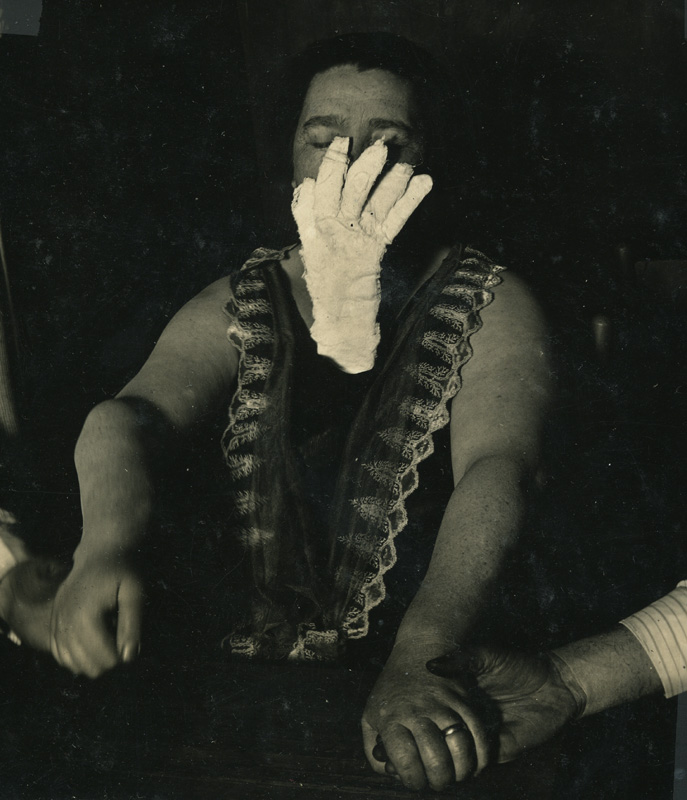

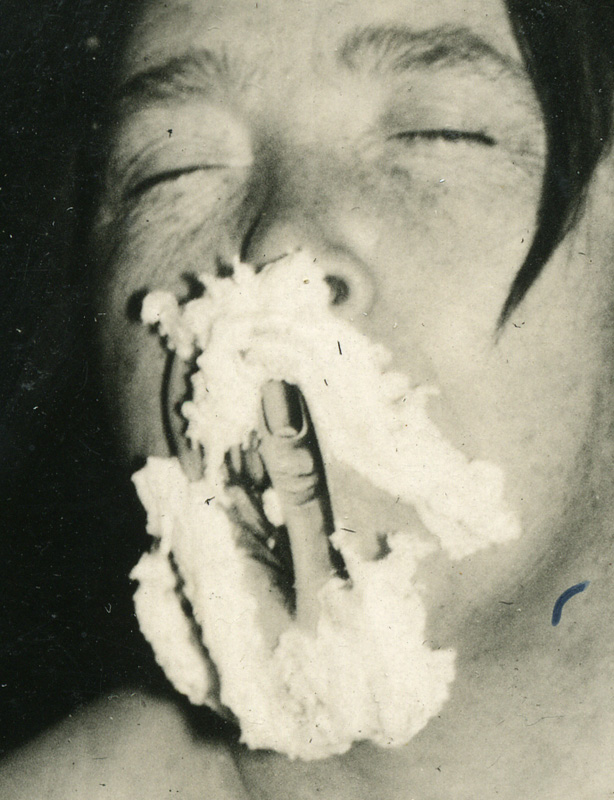

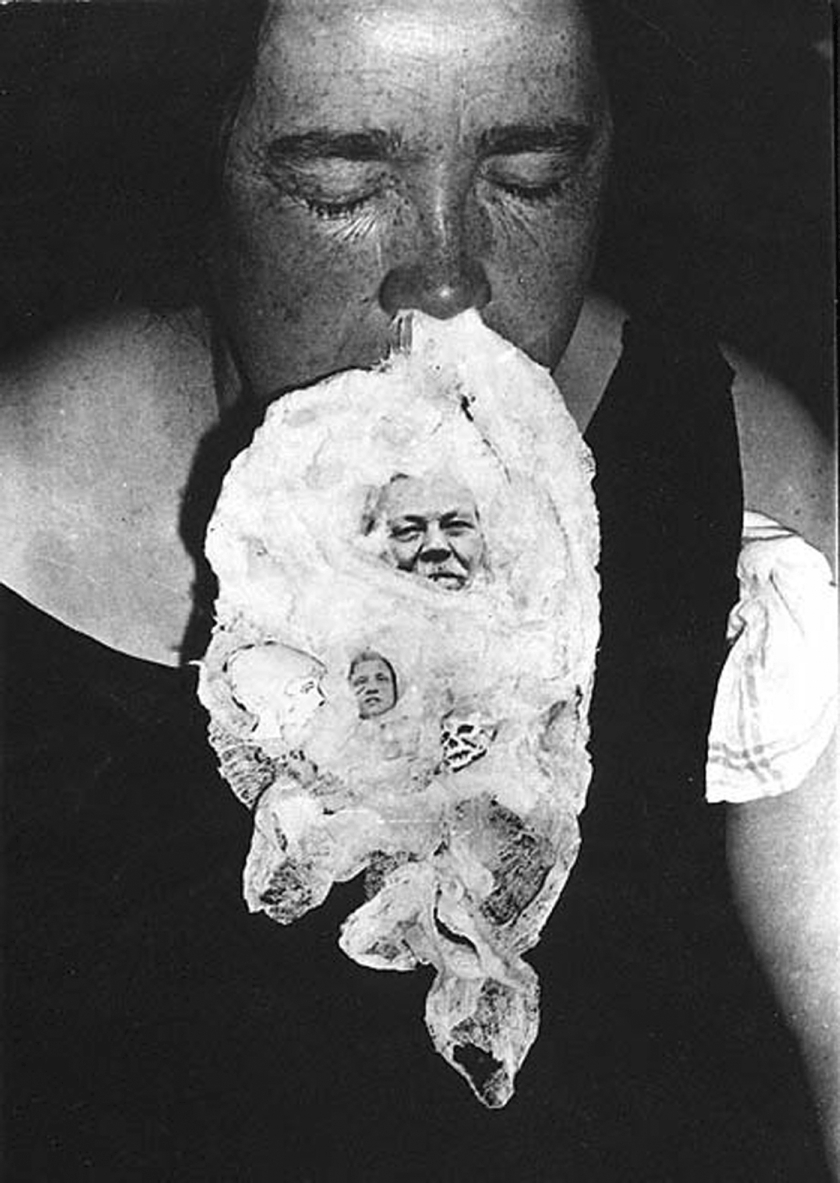

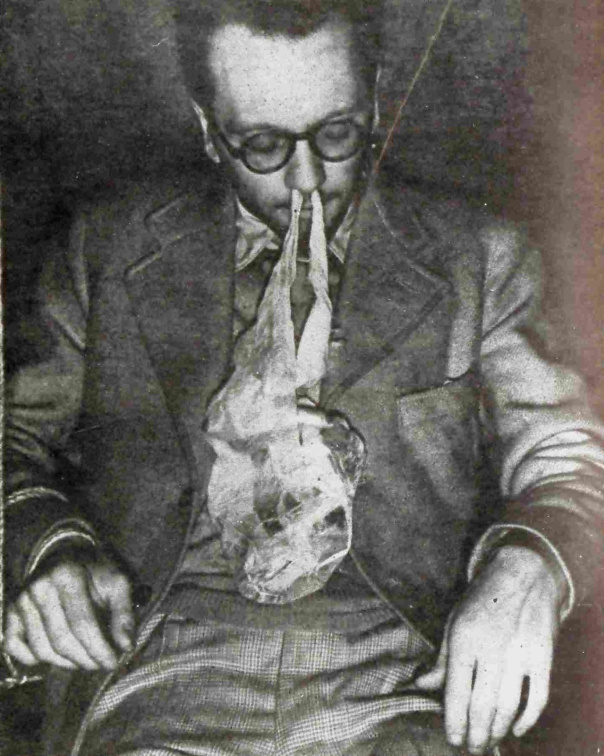

According to spiritualists, it was a substance that would be externalized by the bodily orifices of the medium during a séance. Vaporous in nature, it could take the form of a hand or a face, but in all the existing photographs of course, it looks more like pieces of gauze, tulle, cheesecloth, rags or even as obvious as a cardboard cutout.

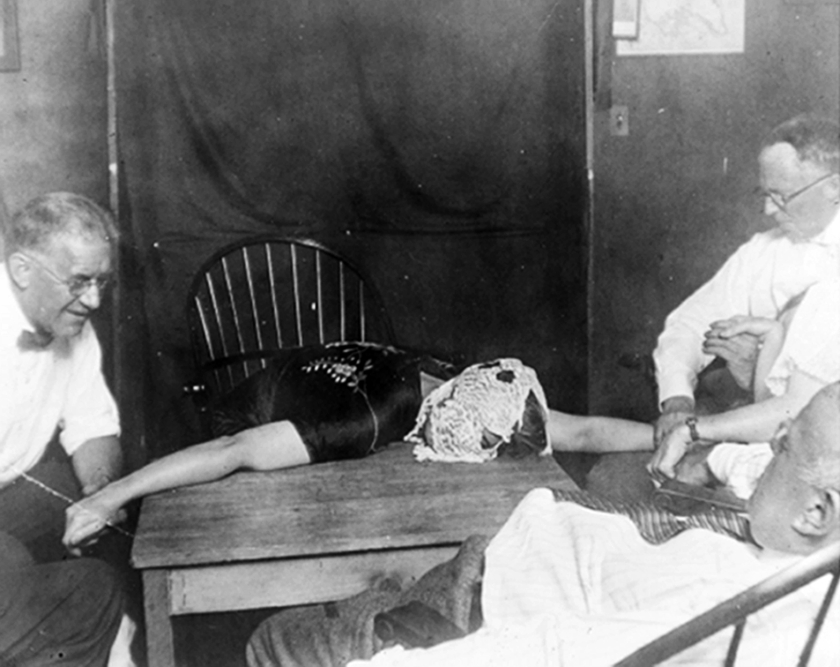

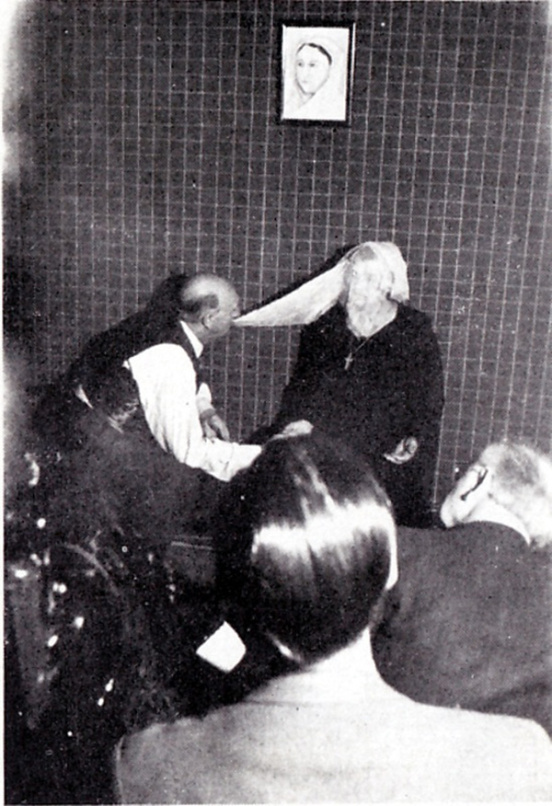

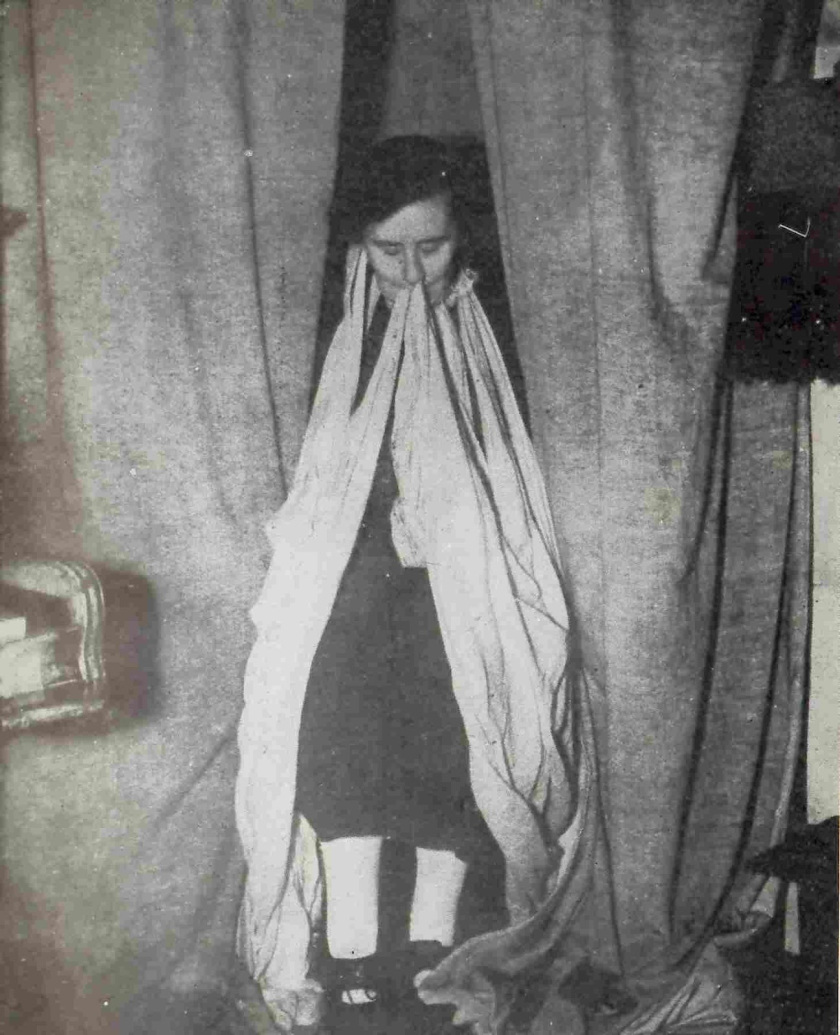

After Charles Richet was named president of the Society for Psychical Research in the United Kingdom, he began studying and investigating famous mediums such as Eva Carrière and Linda Gazzera (pictured above during a séance). He claimed that Gazzera was a genuine medium who had performed psychokinesis and reported objects moving during the séances. Gazzera was exposed as a fraud in 1911 and skeptics accused Richet of being duped by the tricks of fraudulent mediums. He moved back to Paris where he became the president of of the International Institute of the Metaphysical.

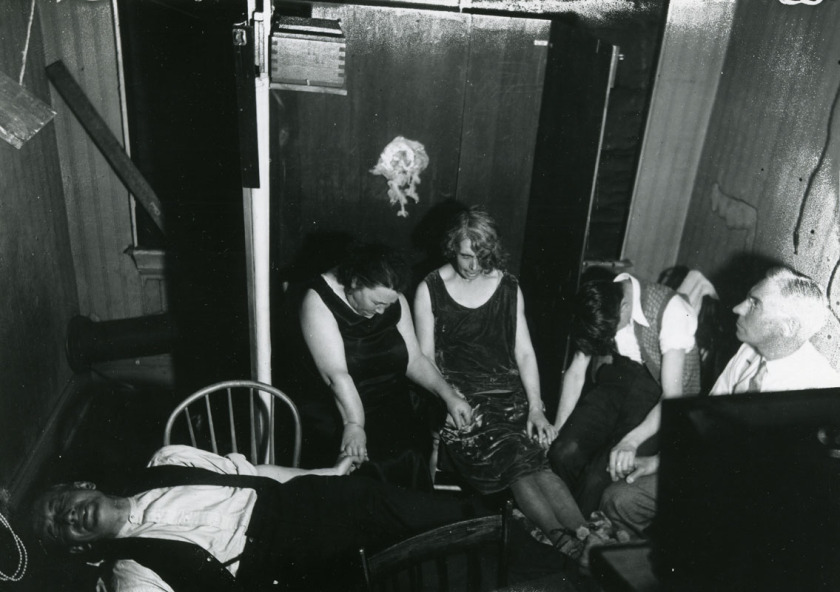

A well-known medium, Mina “Margery” Crandon conducting a séance

Ectoplasm was proved on many occasions to be fraudulent where the mediums had used some rather sickening methods of swallowing and regurgitating cheesecloth, textile products smoothed with potato starch or even paper, egg white or butter.

Eva Carrière used cut-out paper faces from newspapers and magazines. One Danish medium was caught hiding ectoplasm in his rectum. Another famous medium, Mina Crandom, was known for producing ectoplasm in the shape of a hand that came from her stomach and waved about during her séances. The ectoplasm turned out to be made of from a piece of carved animal liver. Her case was described as “the most ingenious, persistent, and fantastic complex of fraud in the history of psychic research.”

Eva Carrière used cut-out paper faces from newspapers and magazines. One Danish medium was caught hiding ectoplasm in his rectum. Another famous medium, Mina Crandom, was known for producing ectoplasm in the shape of a hand that came from her stomach and waved about during her séances. The ectoplasm turned out to be made of from a piece of carved animal liver. Her case was described as “the most ingenious, persistent, and fantastic complex of fraud in the history of psychic research.”

via

Conveniently for the medium, it was said that touching the ectoplasm, or exposing it to light, would make it disappear and snap back violently, causing injury to the medium.

For this reason, medium could insist that séances take place in near darkness and that attendees not approach or come close to the mediums.

The famous magician Harry Houdini was one among many investigators who actively sought to expose ectoplasm as trickery. He had used many of their regurgitation tricks himself and knew that their success was owed to the power of suggestion.

via

via

via

via

The exposures of fraudulent ectoplasm in séances caused a rapid decline in physical mediumship, but despite the scandals and exposures, spirit photography remained popular through the end of the spiritualism movement in the 1920s. And although the pictures are known to be fake, they remain as relics of the era and are still fascinating to study.