A few years ago, a worldly friend who’s always in the know posted something to her Facebook wall that went something like this: Mudlarking on the Thames is the best way to spend a Sunday morning in London. She had me at “mudlarking”—I had no clue what it was. It seemed like something curiously obscure. And who doesn’t love to dive right into a good adventure?

Lead image (c) R2cycl3r

Painted by Henry Pether (c) Museum of London

I immediately googled mudlarking and uncovered this amazing world of history and treasures waiting to be found on the Thames foreshore. Throughout early modern times, the Thames was essentially a massive garbage dump where people and its industries threw away their unwanted items. On a somewhat more positive note, it was also a place for tossing coins to make a wish or ask for good fortune.

But before getting into what can be discovered today, let us go back to the late 18th and 19th centuries where the original mudlarks endured difficult conditions and searched for anything of value to make a living.

A tooth found by London Mudlark

Mudlarks were generally impoverished youth between the ages of eight and 15 or seniors. Most mudlarks were male though there were some girls and women amongst them. They scavenged the Thames shores for anything they could find at low tide.

Conditions back then were squalid since excrement and waste would come ashore from raw sewage—not to mention the corpses of humans and animals like cats and dogs.

Antique coins (c) London Mudlark

Coal, rope and old iron and copper nails were some of their finds. Mudlarks sold their loot to rag shops and could expect to earn about three pence per day (relatively speaking, £0.40 today).

North banks of the Thames (c) Museum of London

Let’s fast-forward to the 1900s. “1904 was the last time it [mudlarking] was used as a profession. The hobby starts to occur in the late 1970s,” said a group of curators from the Museum of London.

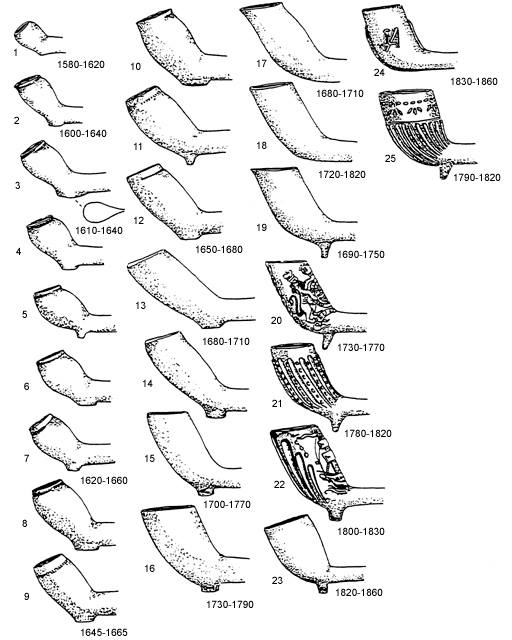

And thanks to the digital age, one of the most popular corners on the Internet for discussions and various finds of current-day mudlarks is the London Mudlark Facebook community. Photos of fascinating finds will make your inner archaeologist drool: old clay pipes, coins, pins, needles, colorful pottery shards, thimbles, combs, and wig curlers are just a few of the items people have uncovered on the foreshore.

Bartmann bottlenecks, manufactured in Europe throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, especially in the Cologne (c) London Mudlark

Clay pipes all found on the Thames foreshore (c) London Mudlark

Bartmann jug shards (c) London Mudlark

Since the Thames’ mud is anaerobic (without oxygen), most of these items are preserved as if they were tossed into its waters a few days ago.

Wig curlers found by London Mudlark

Combs found on the Thames (c) London Mudlark

Antique thimbles (c) London Mudlark

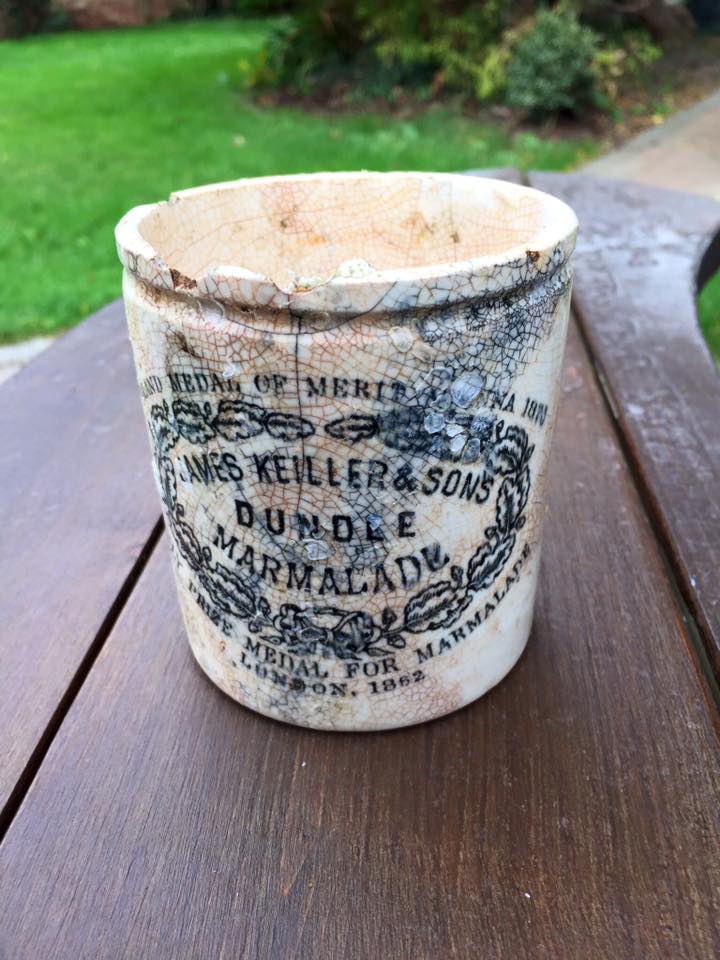

Early James Keiller marmalade jar 1862-1873, found on the Thames foreshore. This was the first commercial brand of marmalade, founded in 1797. (c) London Mudlark

The head of the London Mudlark Facebook community, Lara Maiklem, described some of her most cherished discoveries: “Every find is unique and I’m constantly aware that I’m probably the first person to touch it in centuries, since it was lost or thrown away.

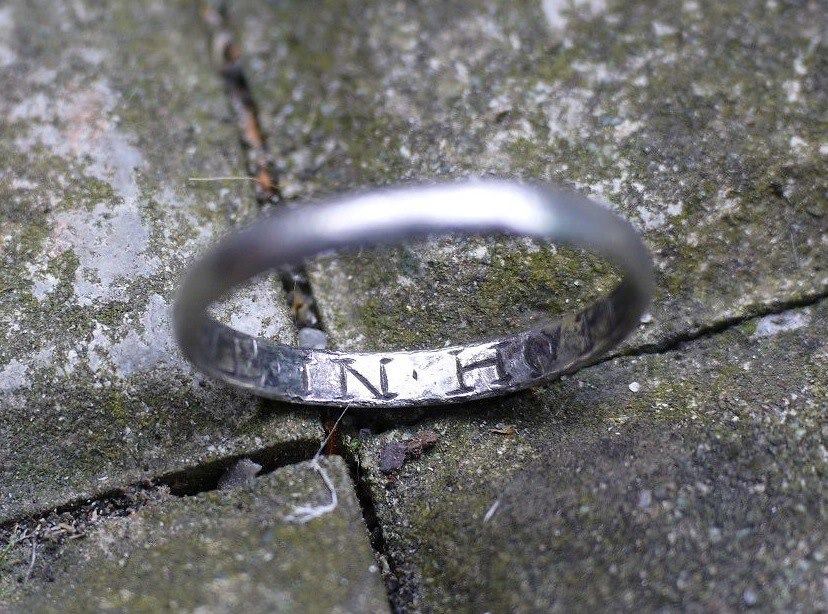

16th century posey ring with the words ‘I LIVE IN HOPE’ engraved on the inside (c) London Mudlark

I’ve found gold and I’ve found some beautiful coins, but my favourite finds are the personal ones – a 17th century pewter bodkin with the initials ‘SE’ scratched into it, a 16th century posey ring with the words ‘I LIVE IN HOPE’ engraved on the inside, and a Roman gambling token with the Roman number 10 (V) scratched on the back. Moments captured in time are also special – pottery with the potter’s finger prints baked into the clay and Medieval and Roman floor and roof tiles with animal prints across them.”

Tudor shoe (c) London Mudlark

And what if Lara’s home was on fire? What would she rescue from her personal mudlarking collection? “The piece I’d save though is my complete Medieval shoe, pulled from the mud in several pieces and currently being conserved at the University of Cardiff. Shoes are so personal and you can still see indents from the heel and toes of this one’s original Tudor owner. It would be a perfect fit for my 4 year-old-son, which gives it that extra personal link to the past.”

Amongst mudlarks, the unforgettable face of a Bartmann Jug rates up there as a coveted, notable find. Coins, too. But for Lara, one of the most prolific and knowledgeable mudlarkers in London, there is one thing she’s still seeking but hasn’t yet found.

“A complete Medieval pilgrim badge still eludes me. I arrived five minutes after a fellow mudlark found one on my ‘patch’ and was even standing right next to someone when he pulled a beautiful example out of the mud, but all I’ve ever found are broken bits and pieces.

A silver cuff link, probably early to mid 20th century found by Lara’s son on the Thames foreshore. “I wonder if someone lost it on the way to the Ascot Races?” (c) Jason Sandy

I always say mudlarking is 10% practice, 10% knowing where to look, 10% knowing what to look for and 60% luck. I just need more luck,” she confessed.

Frozen Charlottes found on the Thames. A form of china doll made from c. 1850 to c. 1920. The dolls had substantial popularity during the Victorian era. (c) London Mudlark

There used to be a time up until recently when “eyes-only” mudlarking required no permit, though today, that is no longer the case. The Port of London Authority expects all mudlarks to have a permit even for a day and to search only in designated areas.

Mudlarkers

For mudlarks of all ages and experience, there are some good practices to follow since the Thames is a tidal river. Lara suggested these tips for anyone up for the adventure: “The one rule everyone should follow is safety. The Thames is a powerful benefactor: twice a day it reveals its foreshore then the waters rise to claim it back again. The currents are very strong and it’s easy to get cut off by the tide, so if you’re thinking of going mudlarking you should always check tide times and keep a close eye on escape routes once the tide turns. I also advise people to take a mobile phone with them so they can call for help if they need it. One beauty of the foreshore is its privacy and relative remoteness, but there’s a good chance there won’t be anyone around to help if you get into trouble.”

Lost passports (c) Anna Borzello

Source: @foreshoreseashore

Note: The first time I went mudlarking, a fellow mudlark (and proverbial guardian angel) warned me to leave soon because the Thames was slowly covering up the stairs which were my exit point. I was so preoccupied with my search that I lost track of time (and tide)! This, too, might be an obvious statement, but it’s wise to arrive an hour or so before the Thames hits low tide to maximize mudlarking time.

19th Century toothpaste tube opening (c) London Mudlark

Other useful items to have on hand include rubber gloves, a good pair of rubber boots, plastic bags with a top closure, and some hand sanitizer. And don’t forget to wash your hands afterwards.

Clay pipe stems (think of them as 17th-19th century cigarette butts) and pottery shards of the Delft, Georgian, Victorian and Tudor variety are the most commonly found objects on the foreshore. If you discover anything of significance, Lara advised that, “Mudlarks are morally bound to report anything over 300 years old to the Museum of London.

I regularly report my finds and they are recorded on the Portable Antiquities Database, a unique resource and an important record of our material history. Anything made of a precious metal, over 300 years old and not a single coin has to, by law, be reported as Treasure.”

For an example of something brought in from mudlarking, I consulted a group of curators at the Museum of London and inquired about one of the highlights in their collection: “This banded mace head from the foreshore is a great find from mudlarking and currently on display in the Museum of London’s London Before London gallery,” they said.

Ever wondered what to do with all those pottery shards? Sculptures, made by Li Xiaofeng

But even if you don’t discover that one incredibly rare item that should be reported, there is much to be learned from the many fragments and whole pieces now lying there in the mud. Lara explained, “The things I find on the foreshore are very ordinary and personal they allow me a window into the lives of Londoners past. Through them I have learned that people don’t change and that you’re never alone in your adversities – people have been there and done it a multitude of times, loving, losing, aspiring and celebrating just as we do today. I’ve also learnt that life is fleeting and that we leave little behind – I will never know the name of the woman who dropped her bodkin or the boy who lost his shoe, their stories are lost to time – so it is important to learn lessons from history, but also to live for now and not for what we think we might leave behind.”

But even if you don’t discover that one incredibly rare item that should be reported, there is much to be learned from the many fragments and whole pieces now lying there in the mud. Lara explained, “The things I find on the foreshore are very ordinary and personal they allow me a window into the lives of Londoners past. Through them I have learned that people don’t change and that you’re never alone in your adversities – people have been there and done it a multitude of times, loving, losing, aspiring and celebrating just as we do today. I’ve also learnt that life is fleeting and that we leave little behind – I will never know the name of the woman who dropped her bodkin or the boy who lost his shoe, their stories are lost to time – so it is important to learn lessons from history, but also to live for now and not for what we think we might leave behind.”

And to borrow a phrase from John Burns, a former MP of Battersea, the rest is “liquid history.”

If you don’t have a permit, you can still experience mudlarking with the Thames Explorer Trust (Thames-explorer.org.uk/guided-tours) or the Thames Discovery Programme (Thamesdiscovery.org/events-home) with an expert guide, who will help you find and identify artefacts located on the surface of the foreshore. For mudlarks of all ages and experience, useful items to have on hand include rubber gloves, a good pair of rubber boots, plastic bags with a top closure, and some hand sanitizer for obvious reasons. Happy treasure hunting!

Thanks to the curators at the Museum of London for their input and to Lara Maiklem, who has a mudlarking book coming out in Spring 2018 with Bloomsbury.