(c) Ultra Panavision

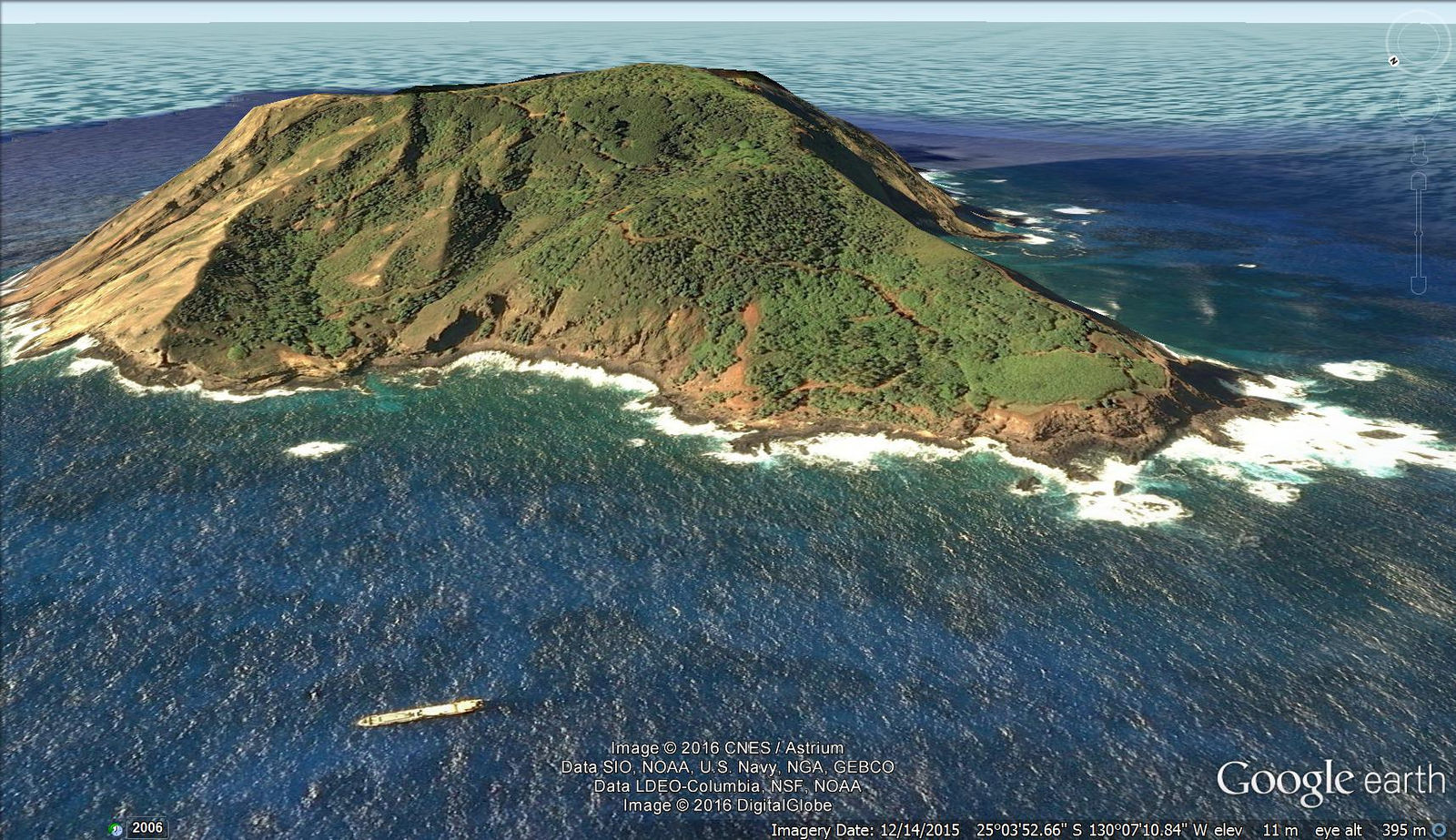

There’s a paradise island in the Pacific Ocean that no one wants to live on. Food and water is plentiful, the land is fertile, it’s surrounded by the most pristine ocean habitat in the world, and yet a potential extinction of the island’s current population (primarily direct descendants of pirates who shipwrecked themselves here 200 years ago) has been predicted for 2045.

Living on the least populous national jurisdiction in the world, the islanders originate from four main families, and their surnames still reflect those of their castaway ancestors. It might sound like a swashbuckling adventure to some at first, perhaps worthy of a children’s tale, but Pitcairn Island is by no means a place for children. In fact as of 2016, despite Pitcairn being an overseas territory of the British crown, the UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office does not allow their own staff based on the island to be accompanied by their children. Why? Read on to learn the very dark past (and present) of Pitcairn…

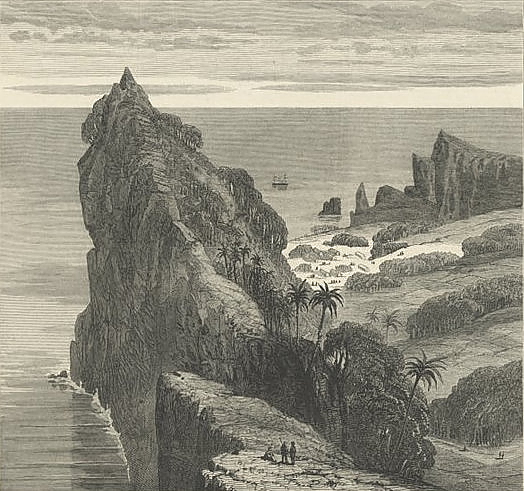

I’ll start at the very beginning, because Pitcairn does have a fascinating history. When the island was first discovered by Europeans, it was entirely uninhabited. Polynesians had previously settled the volcanic land, but the population had been extinct for at least a century before a fifteen year-old crew member of the HMS Swallow, Robert Pitcairn, spotted the land in 1767. The ship’s Captain named the island after the young eagle-eyed seaman and charted its position at 25°2′S 133°21′W, erroneously mapping Pitcairn about 330km west of its actual location. The ship went on its way and when Britain’s famous Captain Cook was sent out to explore Pitcairn six years later, he of course couldn’t find it.

Who should be the first to finally rediscover the isolated island 17 years later? Only nine of the most wanted men in the British Empire, the infamous Bounty mutineers. These nine crewmen led by Acting Lieutenant Fletcher Christian, had become fugitives of the crown after they seized control of the HMS Bounty and set their captain adrift out to sea in a lifeboat along with 18 other loyalists.

(c) Ultra Panavision

Upon setting foot on Pitcairn (an ideal hideout thanks to its erroneous mapping), the English pirates set fire to the Bounty and watched their only means of ever leaving the island again, sink to the bottom of the ocean. The wreck is still visible underwater in Bounty Bay, discovered by a National Geographic explorer in 1957.

Destroying the Bounty was partly a precaution against discovery, but also just as likely a precaution against anyone escaping the island. In the time that mutiny leader, Fletcher Christan, and his fellow fugitives had been island-hopping around the Pacific Ocean in search of a safe-haven, they had also picked up a few Tahitian “passengers” (hostages?) along the way, including six men, eleven women and a baby girl. Christian’s group remained undiscovered on Pitcairn until 1808, by which time only one mutineer, John Adams, remained alive.

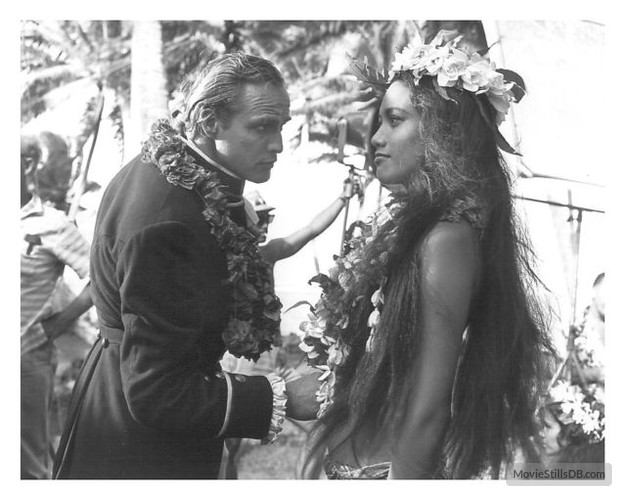

Marlon Brando in MGM’s Mutiny on the Bounty

Despite the island proving to be a haven for the castaways– uninhabited with plenty of food and fertile land, it had been plagued by alcoholism, lawlessness and other ills from the start. In a series of murders early on, more than half of the mutineers, including Christian, had been killed, either by each other or by their Polynesian companions.

(c) Ultra Panavision

Adams used the old Bounty ship’s Bible to restore peace and order to the island, but in-fighting continued. By 1794, all six Tahitian men were dead, some even murdered by the Tahitian women who had been taken as wives by the English. Two surviving mutineers continued on drunken rampages, having figured out they could distill alcohol from a local plant. At the mercy of drunken English pirates, a group of women attempted to escape the chaos of Pitcairn island on a makeshift boat, but failed.

(c) Way Out Wardell

By 1800, Adams was the only mutineer left alive and took responsibility for the well-being of nine remaining women and 19 children. Peace was finally restored and when an American ship accidentally discovered Pitcairn and the unlikely thriving community born out of mutiny, Adams was ultimately pardoned by the crown.

The tale of the Bounty Mutineers has been retold in numerous books and films, with Hollywood stars such as Clark Gable, Marlon Brando, Anthony Hopkins and Mel Gibson glamorising the mutineers as tragic heroes and painting the Bounty Captain who they sent adrift in a lifeboat, as a terrible tyrant.

(c) Way Out Wardell

Two years after the release of MGM’s Mutiny on the Bounty starring Clark Gable, the population of Pitcairn island peaked at 233 in 1937. Today, there are only about 50 permanent inhabitants, making it the smallest population of any democracy in the world.

Over the years, many recovered Bounty artefacts have been sold by islanders as souvenirs, but even such dealings could not rid the island of its sinister reputation.

(c) Ultra Panavision

When I began reading about Pitcairn, I knew I was in for some tempestuous and bloody history about a band of pirates and castaways, but I was not in any way prepared to learn of the shocking modern-day tale that now plagues this paradise island.

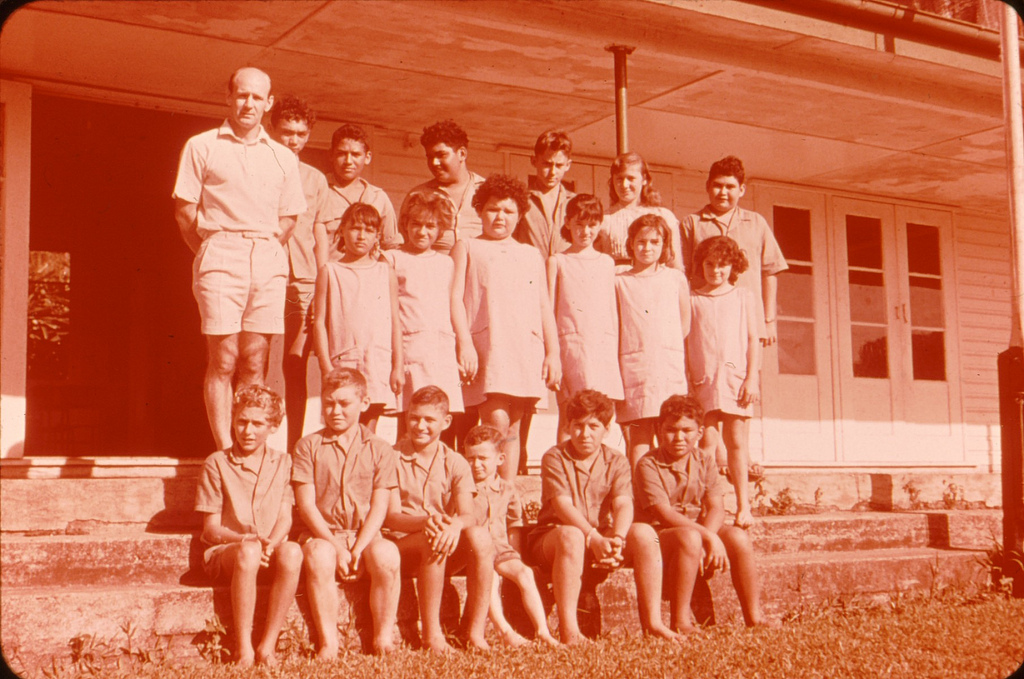

Island council, 1969

(c) Way Out Wardell

In 2004, charges were laid against 13 Pitcairn men, including the island’s mayor at the time, for the rape or molestation of young girls, with most of the girls alleged to have been victims with the crimes spanning several generations. The accused accounted for nearly a third of the island’s male population.

Islanders in 1919

Six were convicted, including the mayor, and sent to a prison built by the British government on the island as a result of the trials. By 2010, they had all served their sentences or were released on a home detention status. That same year, the new mayor was faced with 25 charges of possessing images and videos of child pornography on his computer.

(c) Way Out Wardell

Today, an “entry clearance application” must be made for any child under the age of 16, prior to visiting Pitcairn. Anyone working for the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office sent to Pitcairn, are forbidden to bring their children to the island.

With the population nearing potential extinction combined with the fear of bringing children into the community, the legacy of the Pitcairn pirates looks bleak.

(c) Ultra Panavision

As of 2012, just two children had been born on Pitcairn in the 21 years prior. Despite its efforts, the Pitcairn government’s attempt to attract new migrants have been unsuccessful. For a recent survey that contacted hundreds of islanders who have left Pitcairn over the years, only 33 participated and just 3 expressed a desire to return.

(c) Way Out Wardell

The prospect of migrating to Pitcairn isn’t exactly cheap either. Newcomers are expected to have at least NZ$ 30 000 per person in savings and need to build their own house at average cost of NZ$ 140 000. The average annual cost of living on the island in US dollars is $6577.67.

(c) Ultra Panavision

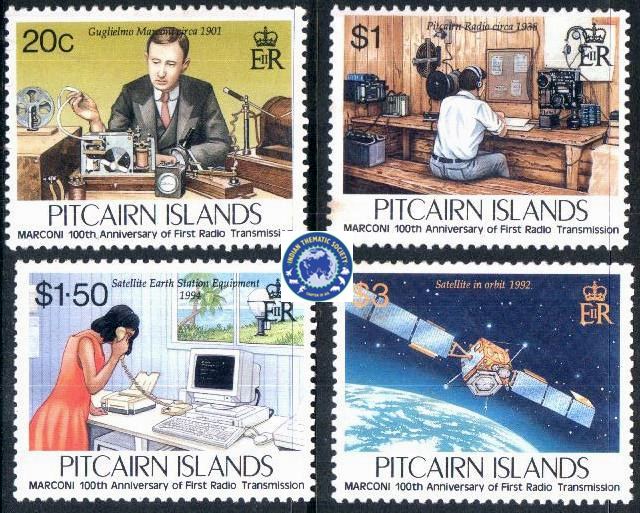

So what about tourism? Surprisingly, even without an airport or seaport, tourism plays a big role on Pitcairn and provides the locals with 80% of their annual income. As of 2015, the island is surrounded by the largest continuous marine protected area in the world around the Pitcairn Islands– more than three times the land area of the British Isles and the intention is to protect some of the world’s most pristine ocean habitat from illegal fishing activities.

The once-strict moral codes, which prohibited dancing, public displays of affection, smoking, and consumption of alcohol, have been relaxed and there is now one licensed café and bar on the island, and the government store sells alcohol and cigarettes. Same-sex marriage also became legal in 2015.

Pitcairn is looking for new residents and currently accepting formal settlement applications. If you can get past this unsavoury small print of this tropical paradise, you can even get to know the island on Google’s Street View. If you want to.