Derelict mining village, Northumberland, 1967

For some 30 years, a collection of nearly 4,000 slides sat undiscovered in a university basement in Sheffield. The lost collection of photographs, found inside a forgotten pile of boxes, has since been digitised by students of the University of Sheffield, and I just spent the morning digging through it.

Back Lane, Blanchland, Northumberland (c) JR James Archive

The JR James archive is a fascinating look at developing post-war Britain, a highly criticised era, blamed for the loss of English architectural heritage at the hands of socialist urban planners. Amassed over several decades, is a notably diverse depiction of England. It contains a considerably picturesque, charming and quaint England alongside some of the most radical concrete buildings the UK has ever witnessed.

I thought we could start with the lighter stuff and ease our way into the concrete jungle…

Newlands Pass in the Lake District, October 1974 (c) JR James Archive

Elm Hill, Norwich, October 1966 (c) JR James Archive

Meteor Street, Cardiff (c) JR James Archive

Old Queens Head Pub, Pond Hill, Sheffield (c) JR James Archive

Thaxted, Essex (c) JR James Archive

JR “Jimmy” James was chief planner at the Ministry of Housing and Local Government from 1961-1967, as well as a professor at Sheffield University before his untimely death in 1980. He was known as a “titan of post-war planning”, lumped amongst those responsible for having destroyed many post-war British towns.

Watling Street, Thaxted, Essex (c) JR James Archive

Oxford Street, Malmesbury, Wiltshire (c) JR James Archive

Kings Lynn (c) JR James Archive

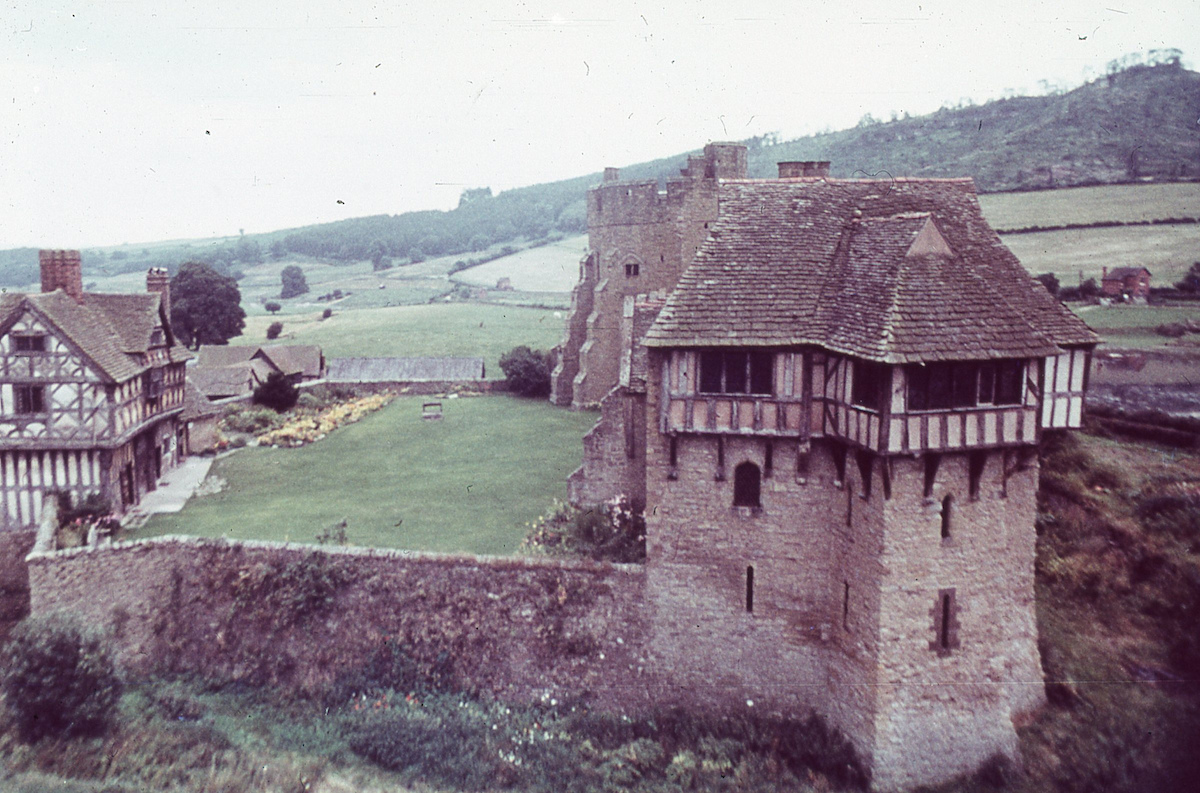

Stokesay Castle, Shropshire, View from North (c) JR James Archive

The Iron Bridge, Ironbridge, Shropshire, 1979 (c) JR James Archive

Pantiles, Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England (c) JR James Archive

Pantiles, Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England (c) JR James Archive

Lift Up Your Skirt And Fly was a banned lyric in “Desdemona” by the English cult band John’s Children. These buildings in this photo were soon demolished for the construction of the “Sheffield Town Hall Extension” or ‘Egg Box Building’, a failed development which was later demolished too.

Moon Street, Cardiff. All of the buildings on the right hand side of System Street as viewed above, have subsequently been demolished for the construction of Adamsdown Primary School. Circa 1967.

View of Plum Street in Oldham

After the devastation of the World War II Blitz, England was faced with chronic housing shortages. To solve the overcrowding, town planners came up with utopian experiments to build “new towns”, “streets in the sky” and “garden cities”. Influenced by Brutalist architects like Le Corbusier, more than 20 of these designated “new towns”, were built in the first 25 years after the war.

Corner Shop, Sheffield (c) JR James Archive

Parkers Lane, The Broomhill Study, Sheffield, May 1970. What it looks like today.

Housing, Sheffield, 1972 (c) JR James Archive

Junction of Watergate Street and Bridge Street, Chester (c) JR James Archive

Housing, Sheffield (c) JR James Archive

Comet Street, Cardiff (c) JR James Archive

The Nursery buildings, New Lanark. Under the ownership of Robert Owen, a Welsh philanthropist and social reformer, New Lanark became an epitome of utopian socialism and an early example of a planned settlement and thus an important milestone in the historical development of urban planning.

New Lanark school (c) JR James Archive

Abbotsford Place, Glasgow (c) JR James Archive

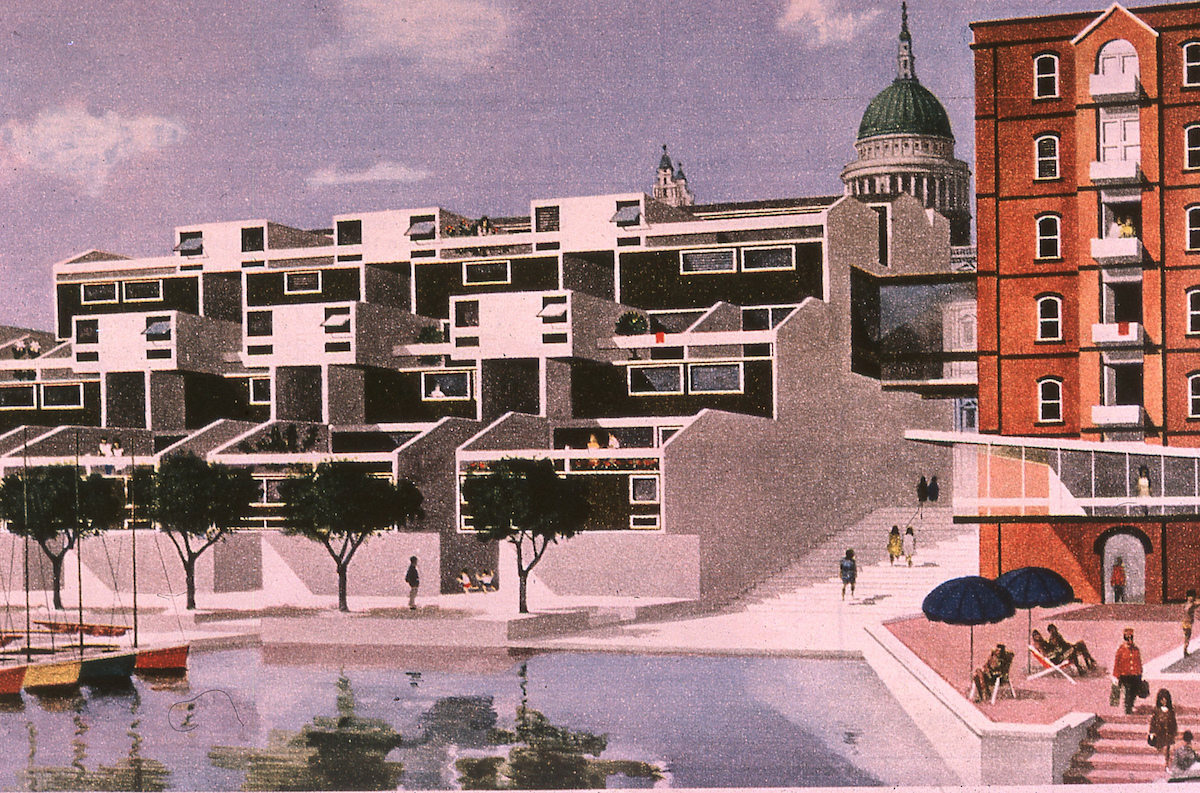

North Bank regeneration proposals, London. The Jr James Archive also contains a large collection of fascinating planning-related photos, maps and plans spanning many decades.

Jimmy James was a planner in favour of the “garden city”; of building outwards rather than upwards in modernist high-rise blocks. More often than not however, politicians overruled planners like Jimmy to keep the population close to the city. By the 1970s, many post-war developments began to reveal social problems and soon came to symbolise an altogether dystopian future.

The Brunswick Centre, Bloomsbury, London, April 1972 (c) JR James Archive

Stevenage Town Centre (c) JR James Archive

City Arcade, Coventry (c) JR James Archive

Howden East, Livingston

It’s a funny time for Brutalist architecture these days. It’s spent the last three or four decades being reviled in the public view, and yet today, infamous modernist buildings such as London’s infamous Trellick Tower or The Barbican (both now listed landmarks) are finding an unlikely and renewed appreciation, considered desirable, fashionable and in some cases, expensive real estate.

Harlow New Town housing, Broadway Avenue, Essex (c) JR James Archive

New Town housing, Harlow, Essex (c) JR James Archive

East Anglia residences (c) JR James Archive

Park Hill, Sheffield, image taken around 1970

Growing up in England, I hated the stuff, and some of it really is awful. But lately? I find myself drawn to Brutalist architecture in the same way I’m still fascinated by nostalgic and old world architecture. I’m not saying I’d prefer to live in a subtopian concrete box over a quaint little Georgian maisonette on a cobblestone street– not just yet anyway. But they’re both part of our history, aren’t they?