“Thomasson: noun \ to-ma-son \ a preserved architectural relic which serves no purpose”. We’ve all come across an example at one time or another– probably didn’t give it too much thought and surely had no idea these random urban oddities actually had a name, let alone an entire movement dedicated to observing them as conceptual art. That’s right, art. People have written books about Thomasson, formed street observation societies to find them (notably in Japan) and even identified a classification system of categories for them. On Instagram, there are over 3,000 posts alone under the Japanese “Tomasson” hashtag: トマソン. I don’t know about you, but I feel like I just found a trapdoor to another secret level in the game of life.

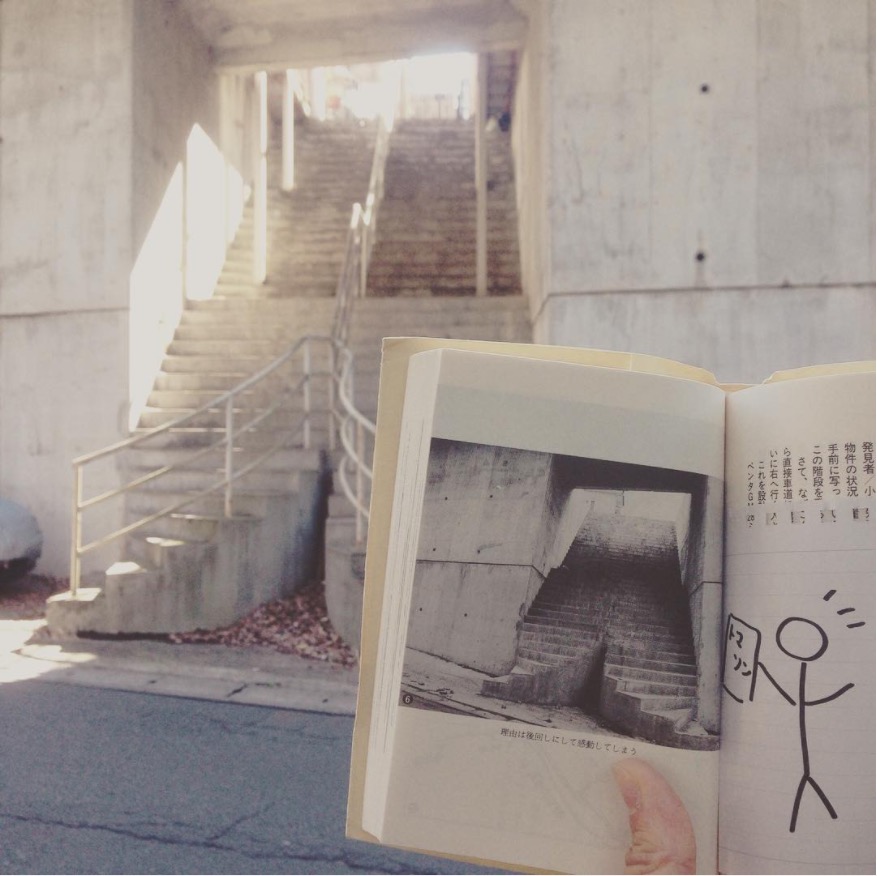

It all started back in the 1970s when a Japanese artist, Akasegawa Genpei, noticed a staircase leading to a blank wall with a handrail that showed peculiar signs of repair, suggesting that it was still being maintained despite being completely useless. With his fellow artists, friends and students, Akasegawa began identifying more “useless” staircases, gates, doors and other urban misfits. They were referred to as “hyperart”, deemed even more art-like than art itself because the objects did not appear to have a creator. At least, not an intentional one.

It’s hard to explain exactly why these useless Thomassons would fascinate anyone, but I think what I personally find most intriguing (or amusing), is the implication of laziness in an unexpected place. A Thomasson is just the sort of thing that has “not my job” written all over it.

Don’t get me wrong, I can relate to being lazy. Exhibit A: my empty clay plant pots that have been sitting on my window sill forever despite any life growing inside them having perished long ago.

But when it comes to urban planning and architecture, isn’t there supposed to be a level of responsibility that comes with the task? Did someone along the line literally make the decision to say– Who cares? Just leave it there.

I guess so! And it’s a little bit baffling.

A textbook Thomasson is a staircase leading to nowhere. But to be truly considered a real Thomasson, there must be a minimal sign of maintenance or intentional preservation to help differentiate it from most urban dereliction. Half the thrill is in the identification of a true Hyperart Thomasson, observing the object for its specific signs and characteristics.

There are also twenty different Thomasson categories that have been created, a handful of which I’ll list below based on the categories in Chikuma Shobō’s “Thomasson Illustrated Encyclopedia”:

The Useless Staircase (Japanese: Muyō kaidan 無用階段): Also known as a Pure Staircase. A staircase that only goes up and down. Most used to have a door at the top. Some useless staircases exist that were useless right from completion, due to changes or mix-ups in the design.

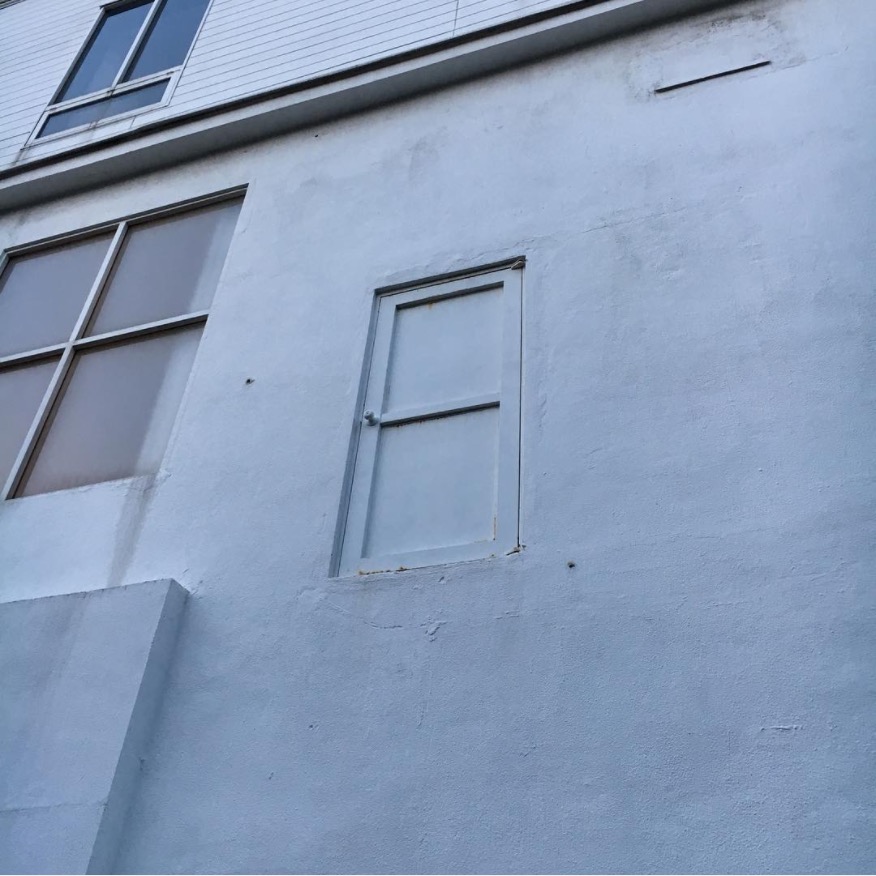

The Elevated type (Japanese: Kōsho 高所): These objects are normal themselves, but exist in a higher than normal place, therefore seeming strange. For example, a door with a handle on the second floor of a wall. These often appear when staircases are torn down. They can also appear when a winch or crane is kept inside the building, but a standard door is used on the outside.

The A-bomb type (Japanese: Genbaku taipu 原爆タイプ): A 2-D Thomasson. The outline of a building that remains in silhouette on a wall. This can be seen when a section of a tightly packed row of buildings is torn down. Cases that appear due to water are known as Hydrogen bombs. Cases that appear when a hoarding or sign is torn down are known as Neutron bombs (Chūseishibakudan 中性子爆弾).

So what’s with the name Thomasson? Well, it’s a funny story that combines uselessness, art, and funnily enough, baseball.

Around the time that artist Akasegawa Genpei and his peers were exploring their new-found concept, an American professional baseball player, Gary Thomasson, had been signed by the Yomiuri Giants in Japan for a record sum. Genpei was also a baseball fan, and watched as Thomasson played the worst two seasons of his career. He even broke a record for strikeouts in Japan and spent most of his contract on the bench. In a discussion between Akasegawa and his students during his class on “Modernology”, they agreed Thomasson’s useless position on the team was a fitting analogy for “an object, part of a building, that was maintained in good condition, but with no purpose, to the point of becoming a work of art.”

In the early 80s, Akasegawa followed up his newspaper column with a book about Thomasson. The press caught on to the concept which created a “Thomasson boom” and the popularity of the movement spread. It then disappeared for a while before an American discovered the book and published an English translation, sparking a rediscovery of Thomasson over in the United States. You can buy it on Amazon or find the Japanese version here.

And that’s how the surname of a retired Major League Baseball player came to represent something rather unfortunate, or something really quite surreal and wonderful. It depends which way you look at it.

Find the Hyperart Thomasson community on Instagram here

I’d also suggest this fascinating documentary about London’s abandoned system of elevated walkways– textbook Thomasson!