(c) Luke J Spencer

Whilst exploring Provence last summer, I found myself in the small town of Mazan. Nestled at the foot of Mont Ventoux in the Vaucluse, Mazan is a quaint, medieval town, enclosed by a circular wall dating back to the 14th century. Set into the ancient wall are old portes, leading to narrow alleyways, hidden fountains and old homes. One particular hidden roadway led to a beautiful 18th century chateau and its remarkable history. For this elegant home, tucked away behind a medieval wall is the old family home of the Marquis de Sade. It also provides a rare opportunity to lay your head in the same place as France’s most infamous libertine, because the Chateau de Mazan recently became a luxurious hotel.

(c) Chateau de Mazan

In the neighbouring Vaucluse commune of Lacoste, lies another old Chateau once belonging to the De Sade family, also partially restored and renovated; owned by Pierre Cardin, the ruined old castle of Lacoste was the setting for some of de Sade’s most notorious parties.

(c) Gabi Monnier/ Flickr

We’ll be exploring both, trying to follow in the footsteps of the Divine Marquis!

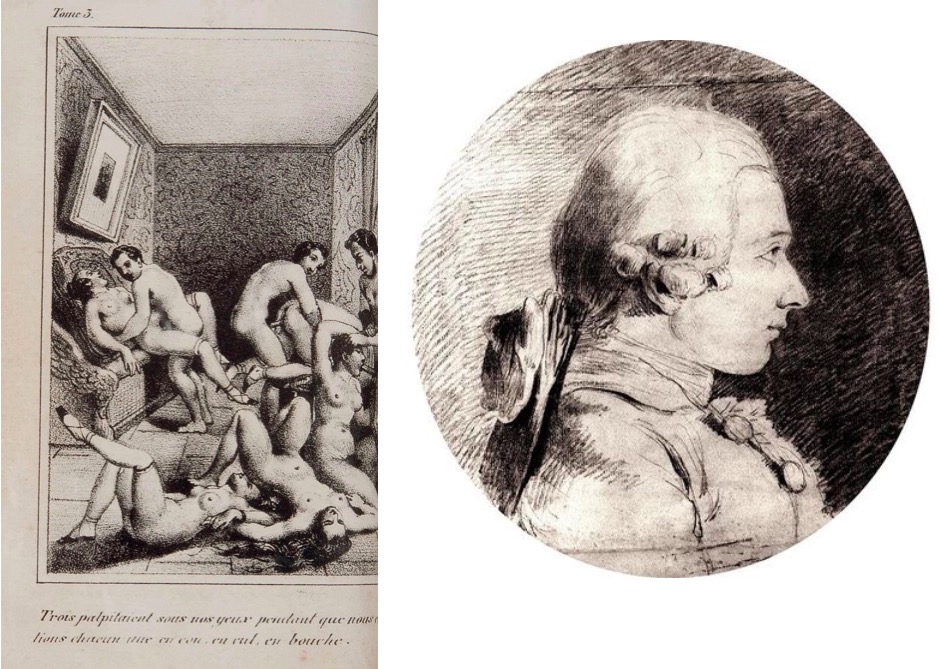

Trying to stay where Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade once did, is somewhat tricky to do today. Unless that is, you like spending your nights in prisons or old asylums. The Marquis spent around a third of his salubrious life interred for his lurid works, which remained banned in France until 1957.

Many of his most infamous haunts no longer even exist. The Bastille prison for example, where the Marquis spent about a decade, didn’t survive the revolution. His manuscript for 120 Days of Sodom did however, stashed away in his prison walls. But you can visit the colossal old Chateau de Vincennes, which hosted the Maquis on two occasions, or the imposing fortress of Miolans, who’s dungeons were so notorious, they were nick named Hell & Purgatory.

(c) Chateau de Mazan

But the Chateau de Mazan is the place which lets you spend the night, and in the height of luxury as well. With what free time the Marquis did enjoy, often enjoyed to the dubious limits which would end up making his surname a noun, was spent between Paris and Provençe.

In order to know virtue, we must first acquaint ourselves with vice. – Marquis de Sade

(c) Chateau de Mazan

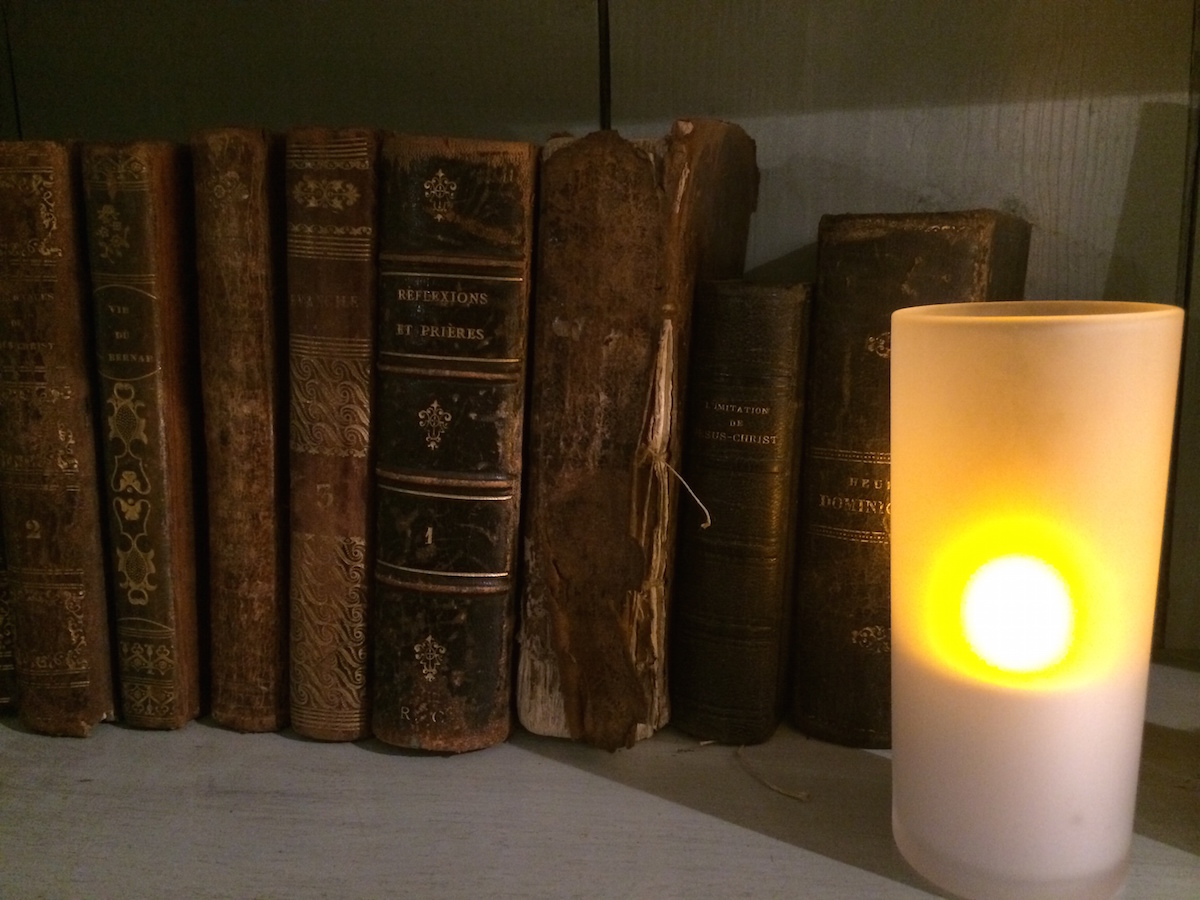

The Chateau de Mazan was built somewhere around 1720. Its beautiful, shuttered exterior, built of local honey-coloured stone, is surrounded by acres of manicured lawns, secret gardens and a cooling, shady swimming pool. It was here that the Marquis organized a theatre festival, of plays he personally performed in, and which is still held today every July in his honour.

(c) Chateau de Mazan

Walking inside the old Chateau, past a marble plaque bearing his name, one of the first things you notice is that there are no whips or chains. But the hotel is delightfully and peculiarly odd; decorated with strange portraits, ranging in age from the 1940s back to lively looking lithographs two hundred years before that.

(c) Chateau de Mazan

Throughout the corridors, stairwells and rooms are life sized statues of devilish looking butlers, wig-less shop mannequins in various states of undress, all under the watchful eye of numerous paintings of naked women. Whilst there’s nothing particularly debauched to be found, it is easy to imagine the wicked Marquis enjoying the decor and ambience.

(c) Luke J Spencer

The Chateau de Mazan survived the Revolution largely intact, as did the de Sade family, in whose hands it remained until the 1850s.

It enjoyed a storied life afterwards, once as a private residence, then a religious boarding school, an old people’s home, until it finally closed its doors in 1999, when it lay abandoned and gradually falling apart until its recent restoration as an elegant hotel.

(c) Chateau de Mazan

I spent the night in the Chateau, dining in the immaculate all white dinning room, enjoying a period 1930s bar, and walking at night through the secluded grounds, where the most infamous libertine of all once walked.

(c) Olivier Thirion / Flickr

But it was nearby Lacoste that saw some of the Marquis most dishonourable parties. The castle on the hilltop had been owned by the de Sade family since 1716. Whilst the Chateau in Mazan survived the revolution, Lacoste was mostly destroyed by the riots and violence. This was the castle the Marquis fled to from the Miolans prison, where he escaped jumping from a window, but not before kindly leaving the guards a brief note of apology. It was also the castle where he hosted some of his wildest and most notorious evenings, which formed the basis of his most infamous works. Perhaps it was this notoriety that led to it being pillaged and largely destroyed during the Revolution.

(c) Jean Marc Favre/ Flickr

Today the haunting Lacoste ruin is still surrounded by controversy; currently owned by iconic French designer, Pierre Cardin, who in the style of true pre-revolution aristocracy bought not only the castle ruins, but a dozen houses in the village, about as many farms, a café, a boulangerie and plans for a golf course. As well as renovating part of the castle as a private residence, Cardin has protected much of the rest of the castle, stabilizing walls and foundations, installing art exhibits and space for theatre and opera amidst the storied ruins and gardens.

Aurélien Calais/ Flickr

But the vast sums spent on restoration by the man who introduced pret-a-porter design has divided opinions in Lacoste. With a population of about 500, some local residents have complained that Cardin has “killed the village” by buying most of it up, and hiking up the property values, whilst others applaud the new found art scene curated by Cardin. “I plan to make this village into a cultural St.Tropez, without its showbiz side,” says the celebrated designer. “I want to restore its authentic glamour, its truth.”

Something that has been restored is the name of the Marquis de Sade himself. For many years after his death in 1814, the Marquis was so reviled that he was unmentionable, even within his own family. But now the Marquis de Sade has been elevated to the canon of French literature. The owner of the title, Hugues, Marquis de Sade runs his own line of luxury goods bearing his ancestor’s signature, selling fine wines, chocolates and patês. “People are fascinated to learn that the Marquis de Sade was not a fictional character,” the current Comte explains, “for five generations, the Marquis’ name was taboo in our family”.

(c) Chateau Mazan

Today the reputation of the Marquis has been restored to such an extent there he featured in an exhibition last year at the Musée d’Orsay. Where once his name was either forgotten, buried in censorship, or spoken of only in hushed whispers, today the Marquis gives his name to the home of one of the 20th centuries most influential designers, and to a secluded charming hotel, hidden away in Provençe.