Kavkazski’s Workshop, St. Petersburg, 1915

Paris may have been the artistic hub of Europe’s cultural life and modern ideas at the beginning of the 20th century, but a majority of its greatest thinkers and artists actually came from abroad, from places such as Spain, the US and even further away, like Russia and its surrounding countries.

Across the Black Sea around 1917-1921, Georgia became a hotbed of artists and avant-garde thinkers who contributed not only to the bohemian artistic underworld of Paris, but also ignited their own artistic movements in the search for a unique Georgian cultural identity back at home in Tiflis, today’s Tbilisi.

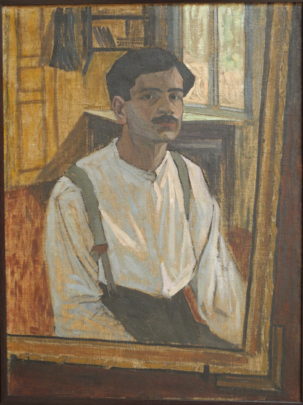

Self portrait

One artist from this Georgian art scene, David Kakabadze, became one of the world’s forgotten modernists, an artist who made his US debut with the likes of Piet Mondrian and Joan Miró, yet his name faded into obscurity in Western Europe and the US after he returned to the Soviet Union. He was an artist who wore many hats, an artist who became a significant figure in Georgian modernism, a film director, a stage designer, a scientist, art researcher and art theorist and someone who invented glassless stereo cinema.

David Kakabadze was born in rural Georgia in the village of Kukhi, near the town of Kioni. Growing up, the budding artist became obsessed with colour, watching the colours and fixated by the shades of green in the Georgian landscape, which he couldn’t replicate from the paint he was allowed to scrape from the bottom of the barrel of the local paint shop. However, a travelling portraitist who painted his father Nestor also sparked an interest in the young artist. He tried to copy the finished portrait, tracing it through a glass pane.

“Imeretia, My Mother”, 1918, David Kakabadze

Much of Kakabadze’s early work would bookend his later and celebrated oeuvre of Imeretian landscapes, as he began painting rural scenes of his native Imeretia, a province in Georgia. He was a child prodigy, drawing all the time and became obsessed with photography, however, after failing the entrance examination into the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, he went on to study physics, mathematics and the natural sciences in St. Petersburg, where he was exposed to the Russian avant-gardes. Kakabadze continued to paint, studying privately with members from the Academy of Arts and branched into cubo-futurism and cubism. Eventually, he followed his calling towards not only art, but also worked in film and stage design, as well as art theory.

A young Kakabadze

When Kakabadze returned to Tbilisi in 1916 after his studies in Russia, he worked as a mathematics and physics teacher, and his artistic passion pushed him to paint his famous “Imeretian Landscapes” in 1917. Kakabadze’s “Imeretian Landscapes” were a curious marriage of proto-cubist proportions with elements of realism. Multicolour boxes are cast in the background as fields in varying shades of colours from pastel to bold; in the foreground, realistic figures and details act as a contrast. His most famous landscape, “Imereti – My Mother,” which the artist completed in 1918, is one of Kakabadze’s most recognised paintings, but as an artist, it was Paris during the 20s that earned him the most esteem…

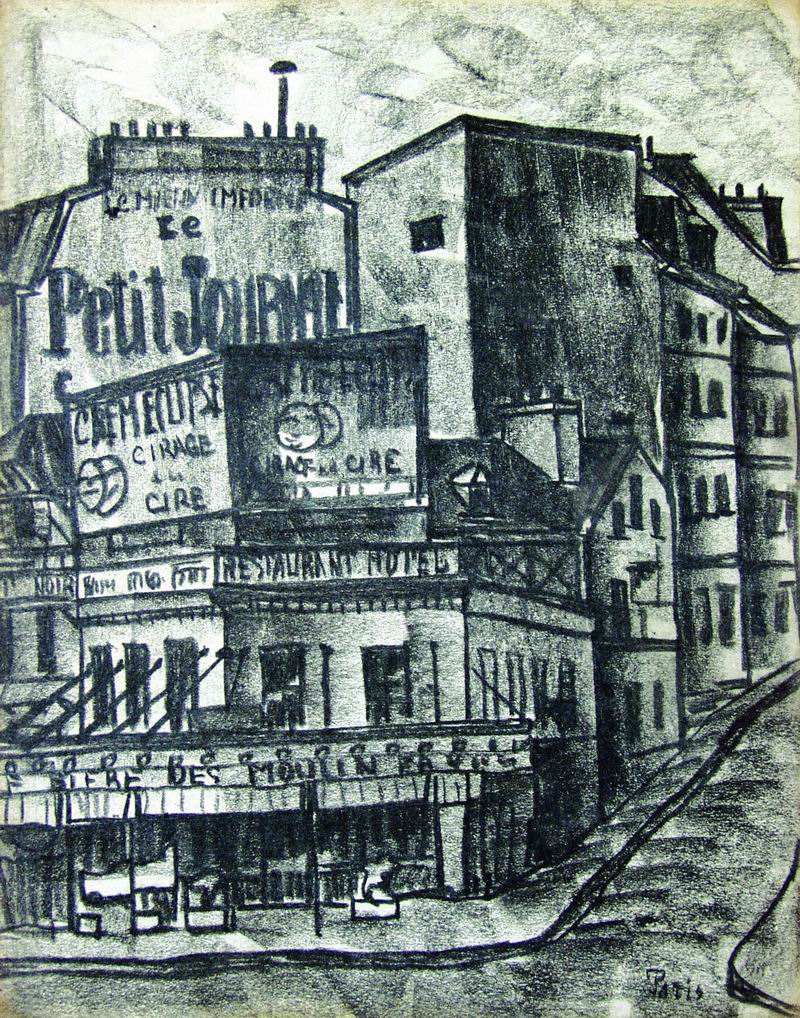

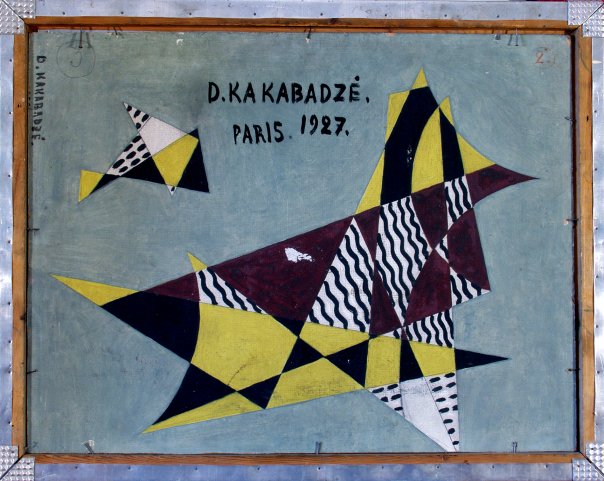

Kakabadze’s Paris work

When in Paris, Kakabadze began to experiment and diversify as an artist, producing works from cubism to abstraction. His love for mathematics and the sciences transmitted through his art, and like Kandinsky, he eventually became a respected art theorist.

David Kakabadze, during his Cubist period

He published numerous texts on space and perception in the context of Eastern and Western art, as well as a number of essays on art theory in both Georgian and in French. Kakabadze also collaborated with Léonce Rosenberg in his bulletin, “L’Effort Moderne” where he printed letters on modern art.

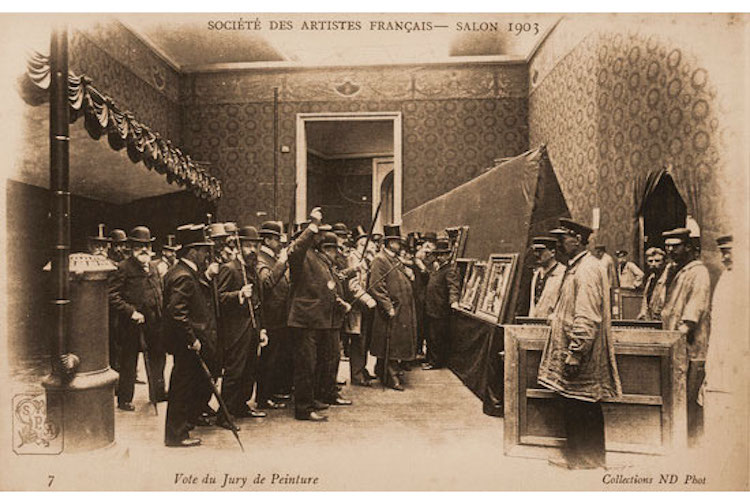

Jury voting in the earliest days of the Salon des Artistes Independents

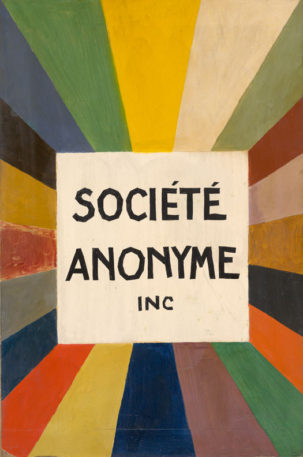

During his time in Paris, Kakabadze showcased his work in the annual exhibition of the “Salon des Independents” and soon became noticed, especially after his work caught the attention of Katherine Dreier and her lover Marcel Duchamp, and the Georgian modernist soon struck up a friendship with the pair. In 1926, the Société Anonyme, created by Duchamp, Drier and Man Ray, in collaboration with Wassily Kandinsky, scouted for avant garde art to exhibit and collect, coming across Kakabadze’s works in the Salon des Independents.

During his time in Paris, Kakabadze showcased his work in the annual exhibition of the “Salon des Independents” and soon became noticed, especially after his work caught the attention of Katherine Dreier and her lover Marcel Duchamp, and the Georgian modernist soon struck up a friendship with the pair. In 1926, the Société Anonyme, created by Duchamp, Drier and Man Ray, in collaboration with Wassily Kandinsky, scouted for avant garde art to exhibit and collect, coming across Kakabadze’s works in the Salon des Independents.

After visiting the artist, his sculpture, “Z, Speared Fish” and 16 water colourswould be included in a large international exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum where Kakabadze’s work, alongside pieces from Piet Modrian and Joan Miró, all made their US debut. While 1926 and 27 were the years when the latter artists received recognition in the US, for Kakabadze this was a fatal time. Moved by his father’s death and homesickness for his family, Kakabadze decided to leave his career opportunities in Paris for Soviet Georgia, after which he lost all contact with the Western artistic world. The exhibition in Brooklyn was the artist’s last international exhibition.

After returning to Georgia, Kakabadze entered his “silent period” and he didn’t commence painting again until 1933. He worked at the Tbilisi Art Academy and like many of his artistic contemporaries, he found artistic freedom in the Kote Marjanishvili Theatre where he became an art director. The avant-garde styles that made Kakabadze stand out from the rest of the crowd were forbidden during the Soviet Union, when Social Realism was imposed…

After returning to Georgia, Kakabadze entered his “silent period” and he didn’t commence painting again until 1933. He worked at the Tbilisi Art Academy and like many of his artistic contemporaries, he found artistic freedom in the Kote Marjanishvili Theatre where he became an art director. The avant-garde styles that made Kakabadze stand out from the rest of the crowd were forbidden during the Soviet Union, when Social Realism was imposed…

Left: Self-portrait by Kakabadze, whose works are notable for combining innovative interpretation of European “Leftist” art with Georgian national traditions, on which he was an expert.

“Processing Gumbrine In The Vicinity If Kutaisi”, Kakabadze, 1951/ AppleMark

Instead, Kakabadze returned to his Imeretian landscapes, but even these landscapes still sparked controversy. Politically, these paintings were criticised for encouraging bourgeois principles, due to the non-uniformity of the field colours. But for the artist in a world of enforced Social Realism, these paintings became the only form of artistic expression permitted to him, and a throwback to his early days as an artist. Many associate these landscapes with Kakabadze as an artist, but it is misguided to identify him solely with these landscapes, some criticise the paintings as being a by-product of the Soviet Union and not truly representative of Kakabadze’s artistic and avant-garde vision.

“Imereti” by David Kakabadze, 1919, oil on canvas (c) AppleMark

David Kakabadze had written and published with Picasso, Braque and Juan Gris, yet by the mid-1930s his name was mostly lost in the Western art world, falling out of contact with his Parisian peers behind the Iron Curtain.

Sailboats (1927) source modernism.ge

Kakabadze’s lack of communication outside of his home country upon his return left his friends in Katherine Dreier’s circle to discuss him posthumously in 1950, even though the artist died in May 1952.

Glassless Stereoscopic Movie System (1923)

Kakabadze left his own contribution to the art world, studying the modernism and avant-garde movements in Paris, working with some of the leading modernists at the time. He also worked to invent a glassless and stereo cinema, combining his background in science, love of filmmaking and photography. Kakabadze embodied the creative thrill of his contemporaries, and who knows where he would be in art history had he stayed in Paris, but his paintings and his landscapes still became an icon in Georgian fine art.

By Jennifer Walker