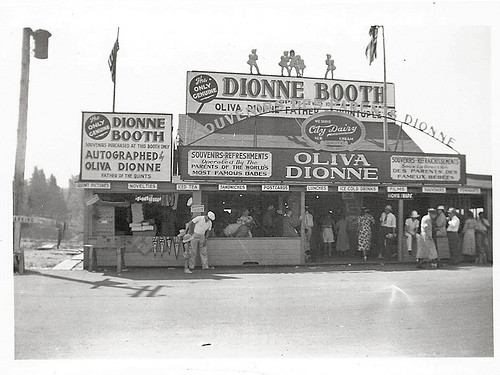

Souvenir Pavilion at Quintland

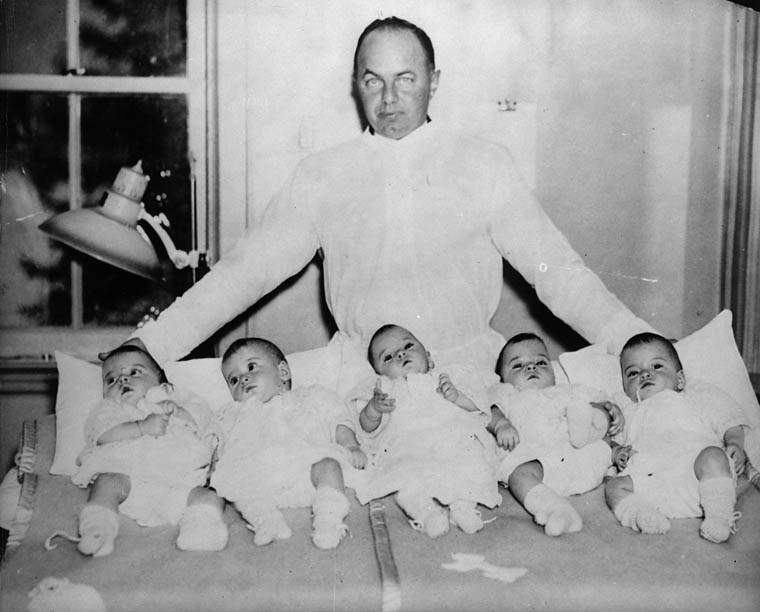

When Yvonne, Annette, Cecile, Emilie and Marie Dionne were born in a rural Ontario house with no running water or electricity in 1934, no one expected them to survive. They were two months premature and at a combined 14 pounds, were each small enough to fit in one hand. But with the help of neighbors and the Canadian Red Cross, they became the first known set of quintuplets to have survived infancy.

Images via Quintland.com

Trouble started for the Dionne family in May 1935 when the girls’ father signed a contract with promoters to exhibit his daughters at the Chicago World’s Fair. Even though he canceled the contract the day after he signed it, the Canadian government was spurred to take action to protect the babies’ health and safety and to keep them from being exploited.

The girls were taken to live across the street from their parents’ house at a hospital compound that became known as Quintland. But instead of protecting the girls, the Canadian government turned the girls into the country’s largest tourist attraction.

The nurses who cared for the quintuplets would also display them on a balcony to crowds below. They always celebrated holidays early so that photographers could capture the experience and sell the pictures to publications.

Their playground was surrounded by mesh and glass that allowed tourists to view the girls three times a day for free as they played. They later said that they were aware of the shadows of people watching them as they played on the playground.

The girls were also studied and researched by scientists at the compound, who x-rayed them and recorded their daily lives in detail, from what they ate to the tantrums they threw.

Eventually, gift shops selling souvenirs with the girls’ faces on them starting popping up around Quintland, along with stands selling stones taken from the Dionne farm that were supposed to promote fertility. The quints’ father even sold them. The government profited, as the gift shop generated as much as $500 million for the province of Ontario in less than a decade, even keeping it from going bankrupt.

Cecile Dionne described it as a circus. In nine years, approximately three million people came to see the Dionne girls at Quintland, making them more popular than Niagara Falls. This is particularly incredible considering that Quintland was located in the middle of nowhere. Some of the era’s biggest stars including Clark Gable, James Stewart, Bette Davis, James Cagney, Mae West and Amelia Earhart made the trip to see the famed Dionne quintuplets.

In addition to being plastered all over postcards, dishes, and dolls, the Dionne girls were used in ads to endorse products such as Quaker Oats, Palmolive, Bee Hive Golden Syrup, toothpaste, and war bonds.

The girls were also made into movie stars. Three films (The Country Doctor, Reunion, and Five of a Kind), fictionalizing their story were made in the 1930s. They also frequently appeared in newsreels during this time and were in an Oscar-nominated short documentary called Five Times Five in 1939.

By 1943 their family had won custody back, but they had a strained relationship with their parents. During the time that the quints were “wards of the provincial Crown,” the parents felt unwelcome when visiting their daughters and rarely went. The girls weren’t allowed to go across the street to see their own family either, and were only allowed to leave the complex a few times in the years they stayed there.

The Dionne parents eventually won custody of their daughters back after a bitter court battle when the girls were 9. At this point, WWII had started and Quintland attendance was down, and their novelty and cuteness were starting to wear off.

But when the girls were reunited with their family, their home life was difficult. The drastic difference between the girls’ sheltered existence at the hospital at Quintland and the rural lifestyle of their parents made for a difficult transition, and the girls also later said that their parents resented them and the position they put the family in. Although the quints continued to make appearances and earn money for the family, their parents forced them to serve meals to the rest of the family do more chores than their other five children. As the girls themselves put it, “There was so much more money than love in our existence.”

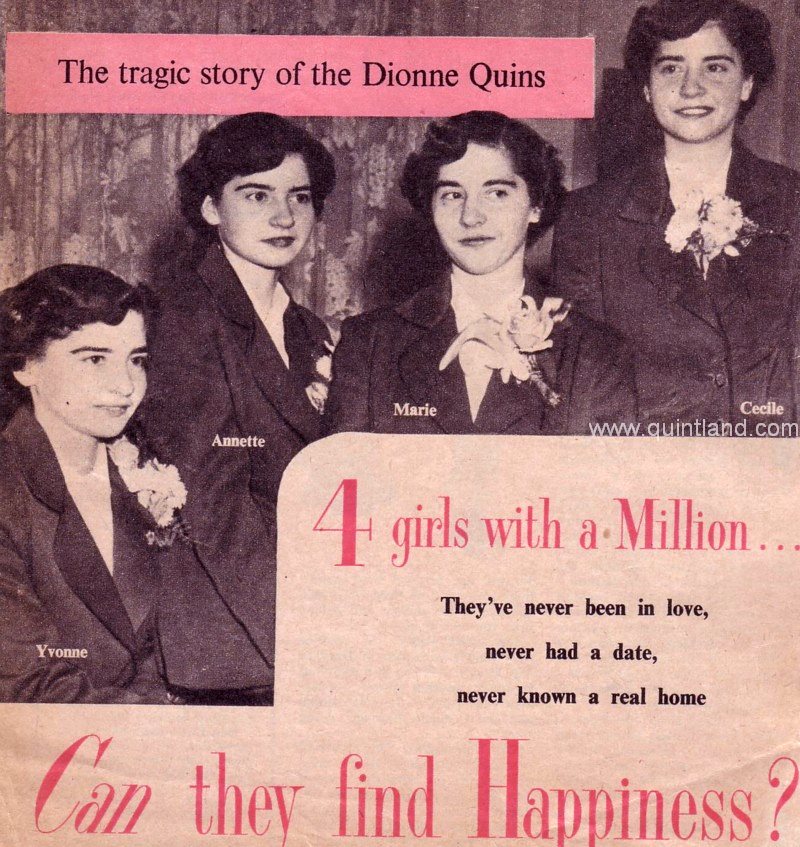

The girls left home at age 18, cutting off contact with the rest of their family, and went on to live relatively normal lives out of the spotlight. Emilie joined a convent and died of a seizure in 1954. When they turned 21, the Canadian government bestowed a (relatively small) trust on the surviving girls for the money they earned for Ontario.

Cecile, Annette and Marie all married, raised families, and eventually divorced. Marie died in 1970 and the three remaining sisters (Annette, Cecile and Yvonne) moved into a house in a suburb of Montreal together in the 1990s. At this point, their trust had nearly run out, and they settled with the government of Ontario for $2.8 million for the exploitation in their younger years. Yvonne died in 2001, leaving two surviving sisters. They continue to live a very quiet, private life that stands in stark contrast to the circus in which they were brought up.