Members of the Situationist International via libcom.org

What if there were walkways over the Paris rooftops, if the metro was open after midnight for pedestrians to navigate by foot, and if all museums were abolished and their masterpieces displayed in restaurants and bars? These were actual proposals put forward by the Situationist International, a playful group formed in 1950s which comprised mainly of artists and intellectuals who sought alternative experiences of urban living with the ultimate aim of creating a better, and more exciting, city for all.

via www.notbored.org

This group is perhaps best known for its involvement in the 1968 Paris student riots, when much of their graffiti could be found all over Paris, including the Situationist slogan “Ne travaillez Jamais” (Never Work). With their politics and theories becoming increasingly popular in the period leading up to 1968, it could be said that without them, the brief but legendary youth rebellion may never have happened.

via www.e-flux.com

The Situationists believed that play was an important aspect of everyday life and they often tried to amuse themselves through activities that were considered to be dubious. They hitchhiked through Paris in the midst of a transport strike with no destination or purpose in mind except to add to the existing state of confusion. They explored the Paris catacombs illegally and entered abandoned buildings after dark, taking considerable risks in the underworld. Many of their other activities were similar to those undertaken by modern day urban explorers and were partially driven by their desire to counter capitalism and to unlock the city. Members of the collective were concerned with the privatisation of space and how the city was becoming increasingly inaccessible to the public. Raoul Vaneigem, a prominent member of the Situationist International, said that “all space is occupied by the enemy. We are living under a permanent curfew. Not just the cops”. The Situationists wanted to combat this and to be able to freely explore the city as their own, a belief that was echoed by many of the other 70 members of the group throughout its existence.

© Brassai

The rebellious group believed that the biggest threat to life was boredom and so, in order to avoid this, they created different games and activities to experience the city in new and exciting ways. One such activity was exploring the city on foot through what they called a dérive, “an unplanned journey through a landscape” using a “mode of experimental behavior” that encouraged them to discover what they loved or hated about the city. We might just call it drifting.

There was no advanced planning, they were lead by their emotions, soaking up the surroundings without worrying about the final destination. According to Guy Debord, the self-proclaimed leader of the Situationist International, dérives were better when experienced as a group. This is a technique which has been adopted by many urban explorers who have been inspired by their work.

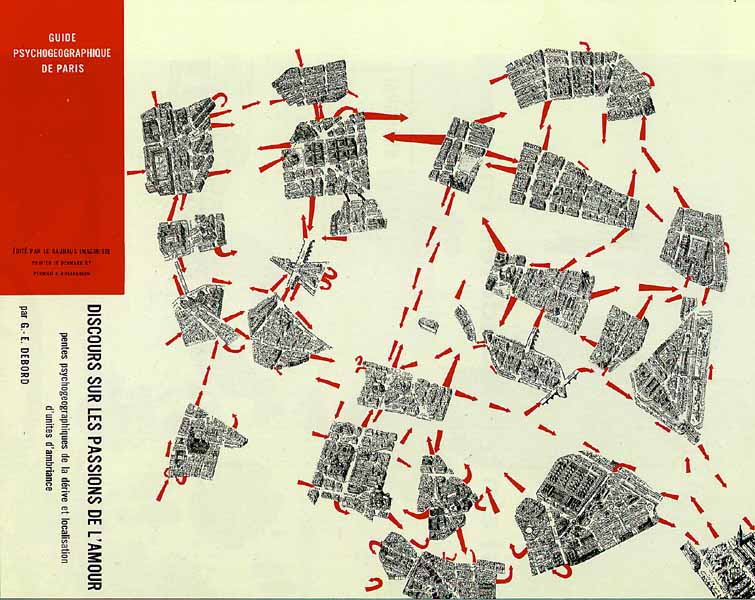

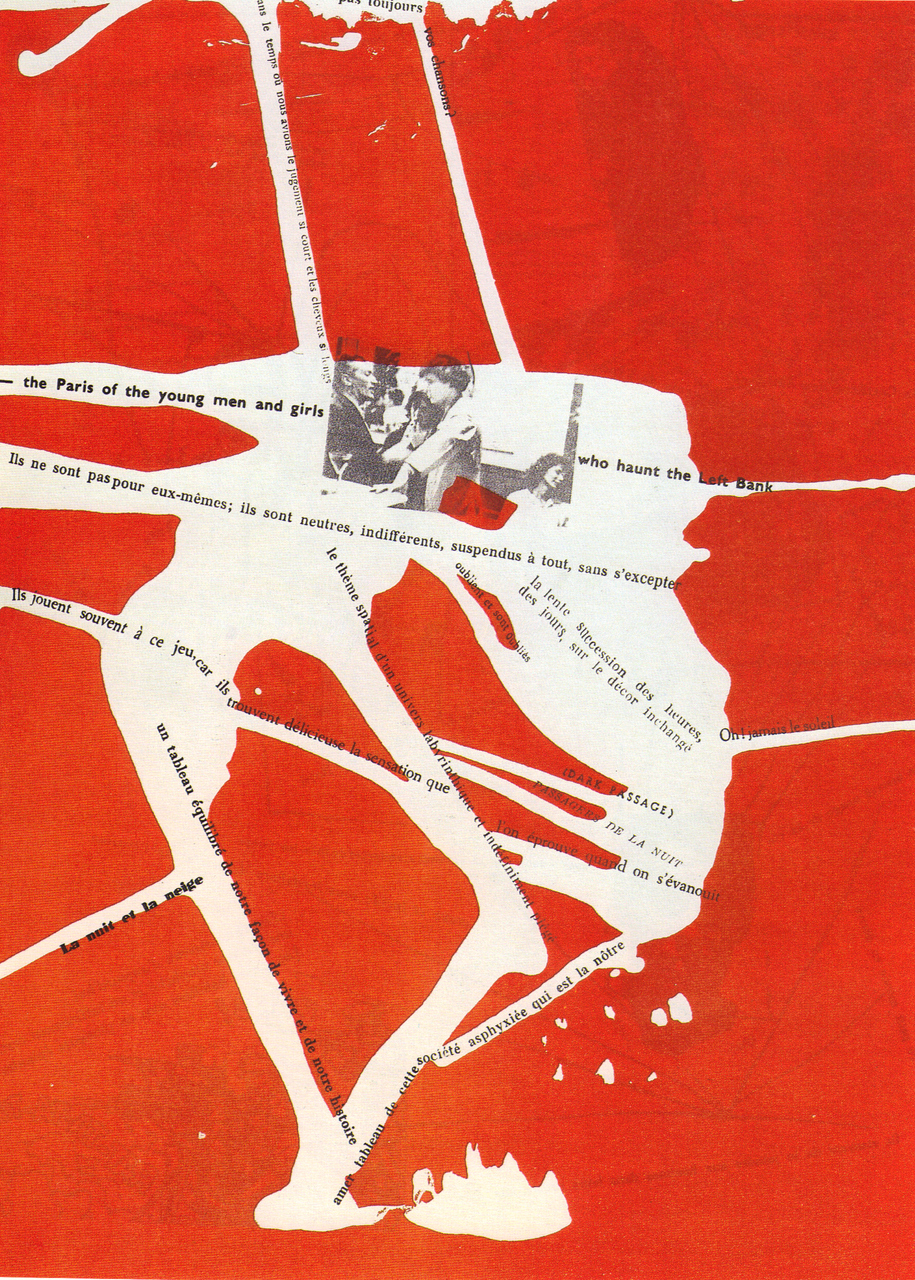

© Guy Debord via Imaginarymuseum.org

Through their explorations and wanderings around the city, they created alternative maps of the Paris, which tracked their paths, movement, desires that they experienced in different places around the city.

© Guy Debord

They also came up with other eccentric proposals that they believed would help to relieve boredom. They wanted public gardens to remain open to all throughout the night and to light them atmospherically. They also wanted street lights to have switches so people could turn them on and off as they pleased. They even wanted to open up prisons as tourist destinations with free access for people to visit as and when they pleased, without distinguishing between inmates and visitors!

via www.notbored.org

However, from 1968, with the ever changing social struggle and increasing tensions between members, by 1972 there were only 2 Situationists that remained and the group was formally dissolved. Despite never seeing their unconventional ideas comes to realisation in the conventional world, many of their visions for a free and liberating city are very much still alive today and have played a prominent role in the history of modern urban exploration.