Before the flapper came about as the embodiment of 1920s femininity, women in the late 1800s and early 1900s had a different role model from which to take cues – the Gibson Girl. She was the feminine ideal of this era and socially, the Gibson Girl had a very defined role. She was upper class, educated, athletic, liberated and progressive, but not too progressive that she might appear “unfeminine” or a threat to men in any way.

She could go to college and even work to fulfil herself personally, however, she would never have been depicted as a suffragette, which was associated with the more radical “New Woman,” a movement of early feminists who sought to actually change the social order.

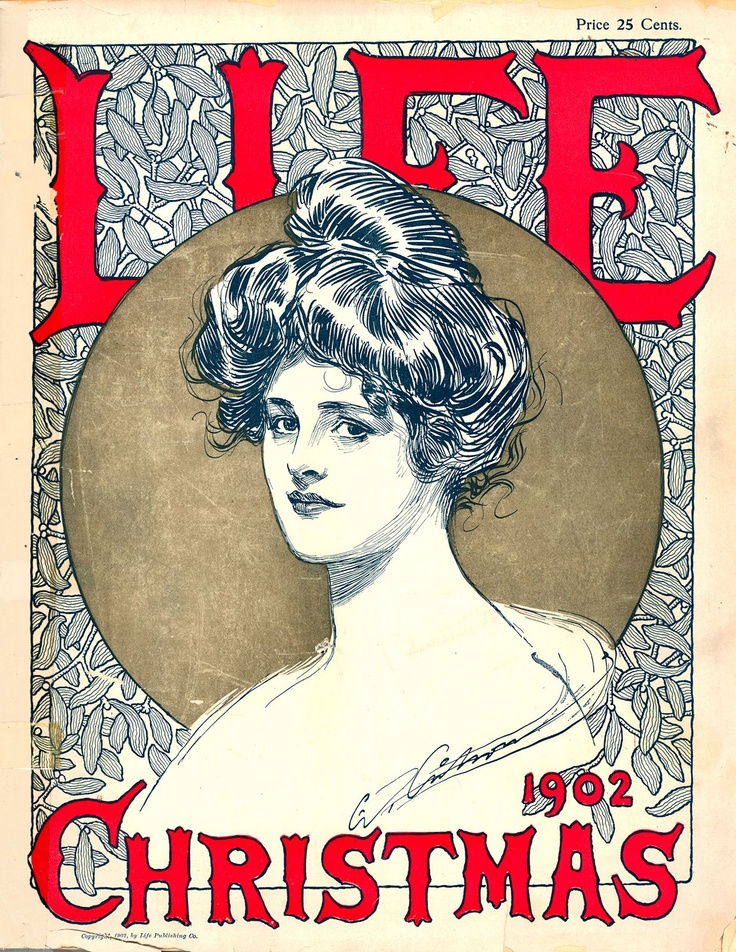

While the flapper has been widely portrayed in literature and film, the Gibson Girl existed primarily in the pen-and-ink drawings of artist Charles Dana Gibson. His sketches began appearing in Life magazine in 1886. Mr. Gibson also drew for other magazines such as Harper’s Weekly, Scribners and Collier’s over the next 30 years. He also illustrated several books and eventually became the editor, and then the owner of Life magazine.

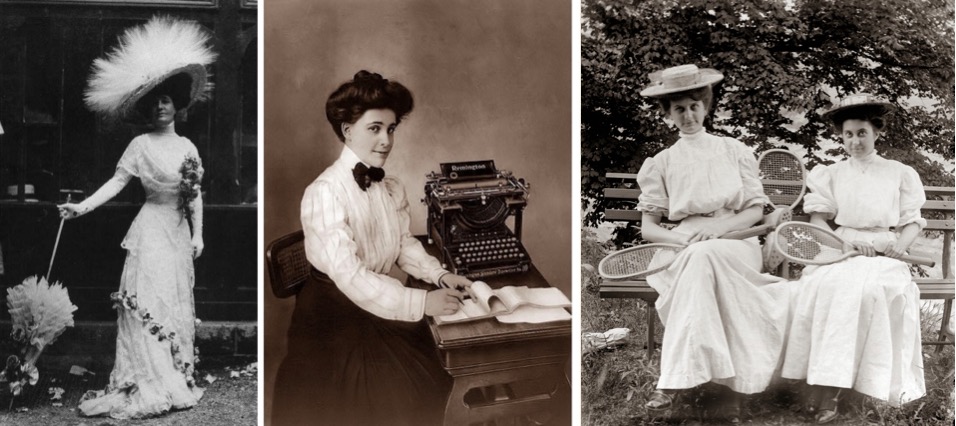

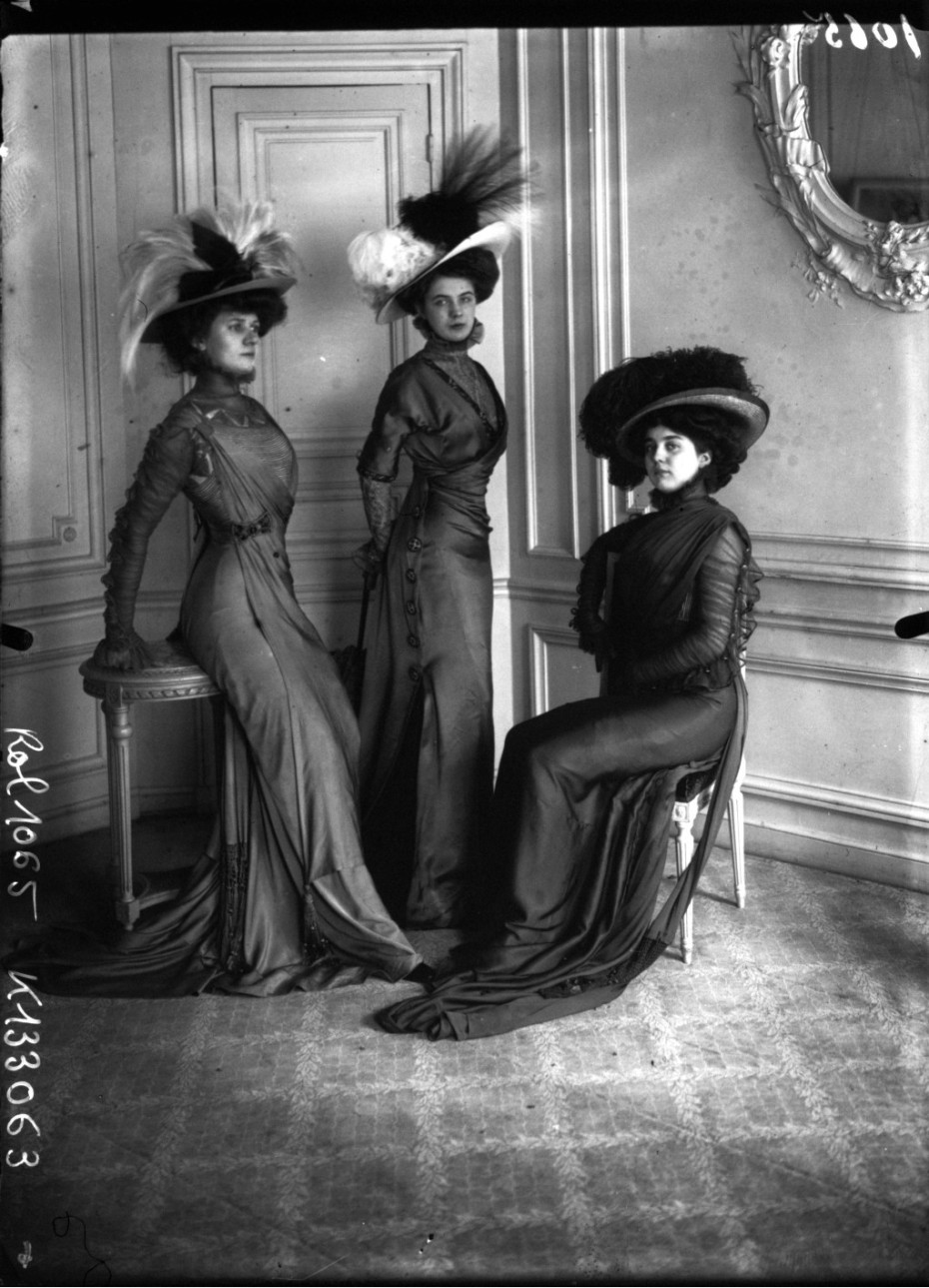

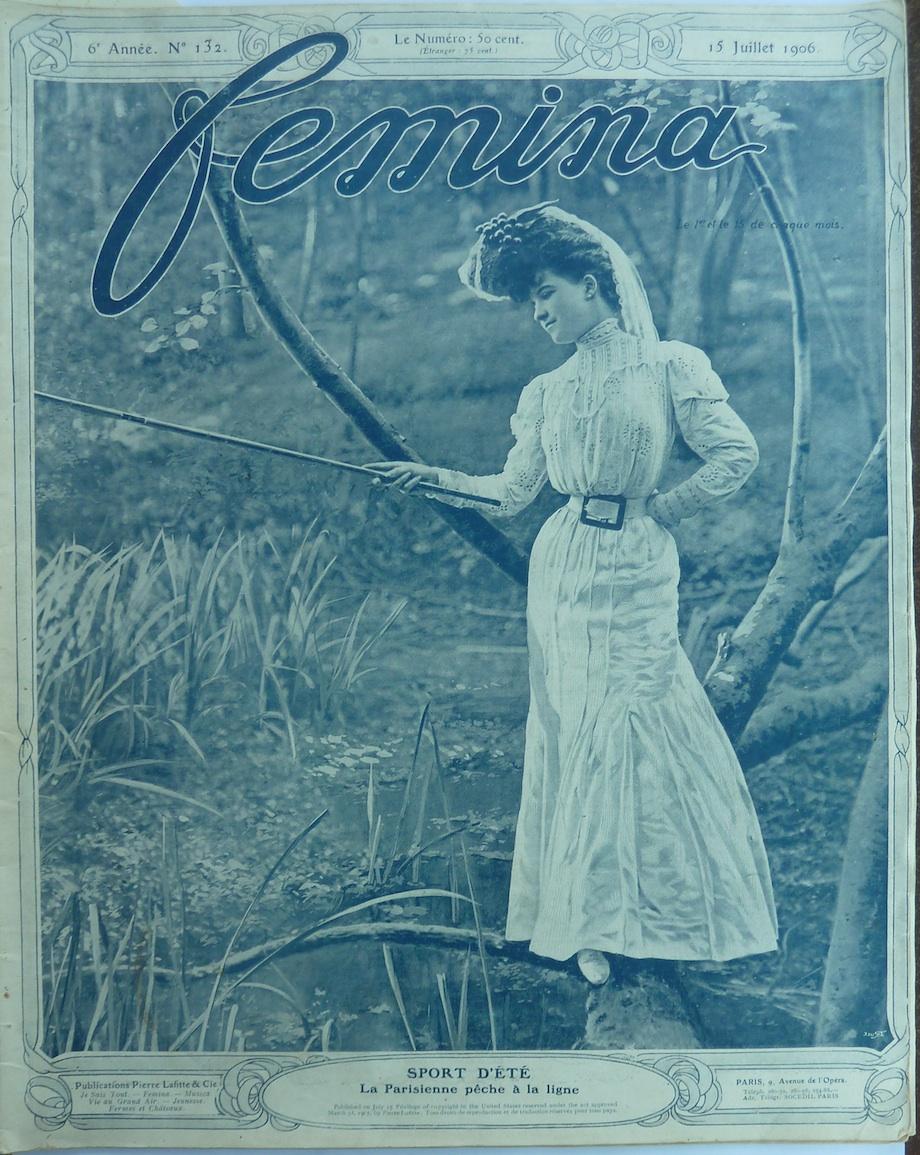

The girls in Gibson’s sketches were defined by a very specific physical look. Her face was delicate, beautiful and youthful and was frequently at ease or had a haughty expression. The signature Gibson Girl hairstyle was long and curly and piled on top of her head in a massive bouffant, pompadour or chignon.

Gibson Girls also had an iconic body shape that combined elements of fragility and voluptuous-ness. She was very curvy, but still tall and slender. Thus the Gibson Girl gave an air of being sexy and curvaceous without being lewd. Women attempted to achieve this exaggerated body shape for themselves by wearing so-called swan-bill corsets that forced their torsos forward and their hips back into an S shape.

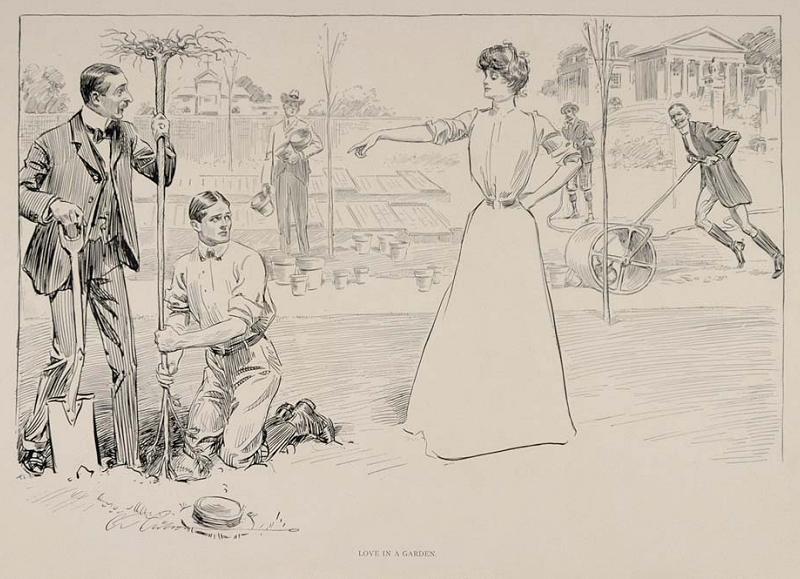

Their intimidating beauty and quasi-liberated status also meant that Gibson Girls were depicted as having interesting relationships with men. Men were often depicted as awkward or clumsy next to the calm, graceful Gibson Girl.

Men would follow Gibson Girls to absurd places or do ridiculous things for them, and could often be seen as targets of Gibson Girls’ teasing. But despite being depicted as equal to or even better than their male counterparts, Gibson Girls never challenged the traditional role of woman as wife and mother.

Although Gibson himself said that the Gibson Girl was a representation of the composite of thousands of women in America, the Gibson Girl was likely more directly inspired by many of the women in Gibson’s life, including his sister, Josephine Gibson and his beautiful wife, Irene Langhorne Gibson, as well her four equally beautiful sisters, one of whom was Lady Nancy Astor, the first woman to serve as a member of the British Parliament in the House of Commons.

Although Irene embodied the physical look of a Gibson Girl, she didn’t always fit the social role of a Gibson Girl. She was active in progressive politics, promoting causes for children and encouraging education and suffrage for women.

Gibson eventually ran a magazine contest to find the girl who most embodied the Gibson Girl, which was won by a Belgian woman named Camille Clifford. Clifford went on to become an “actress” who had only walk-on, non-speaking roles. Despite this, Clifford became wildly famous for her beauty and embodiment of the Gibson Girl style.

Another famous Gibson Girl model was Evelyn Nesbit. Nesbit was the early-1900s version of a supermodel in her own right before she posed for Gibson. She appeared on the cover of many famous magazines of the day, such as Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar and Cosmopolitan, and she was found in many of the ads contained within those magazines.

Gibson’s illustrations were soon seen reflected in a budding form of entertainment—silent films, particularly in the so-called “Biograph Girls.” These were actresses who made films for the Biograph Company. Although all early silent film actresses started off as uncredited (a way for film companies to stop their actors from gaining celebrity status that allowed them to command higher salaries), Biograph eventually bucked this trend and made actresses like Florence Lawrence and Mary Pickford into the first movie stars. These films were seen in many other countries outside the U.S., spreading the image of the Gibson Girl around the world.

Overall, the Gibson Girl was perhaps best defined by a delicate balance of old and new (sexy without being sleazy, liberated without being too progressive). But by the 1920s, the social changes brought by World War I caused the moderation Gibson Girl to fall out of fashion in favor of the more extreme flapper.