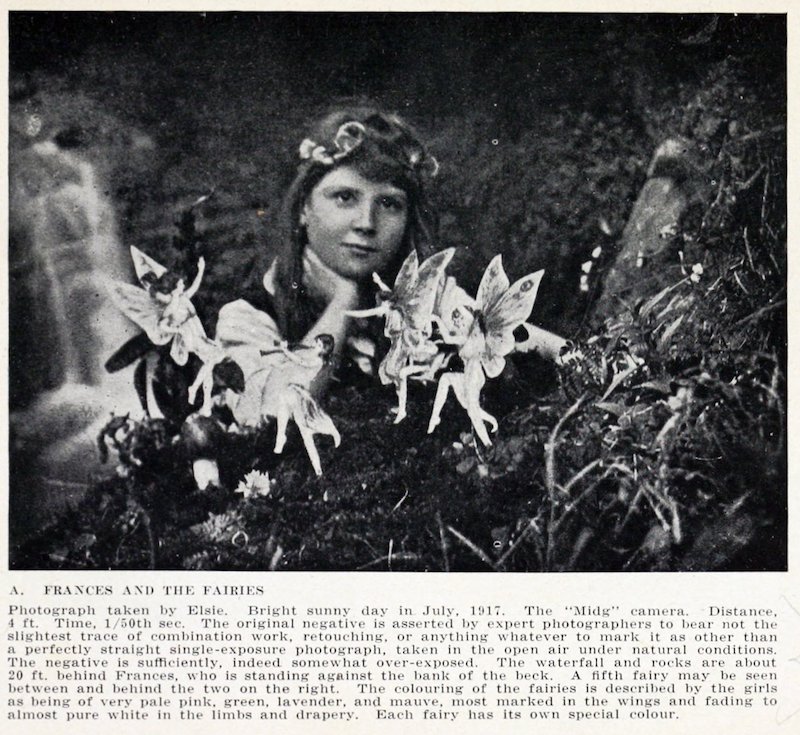

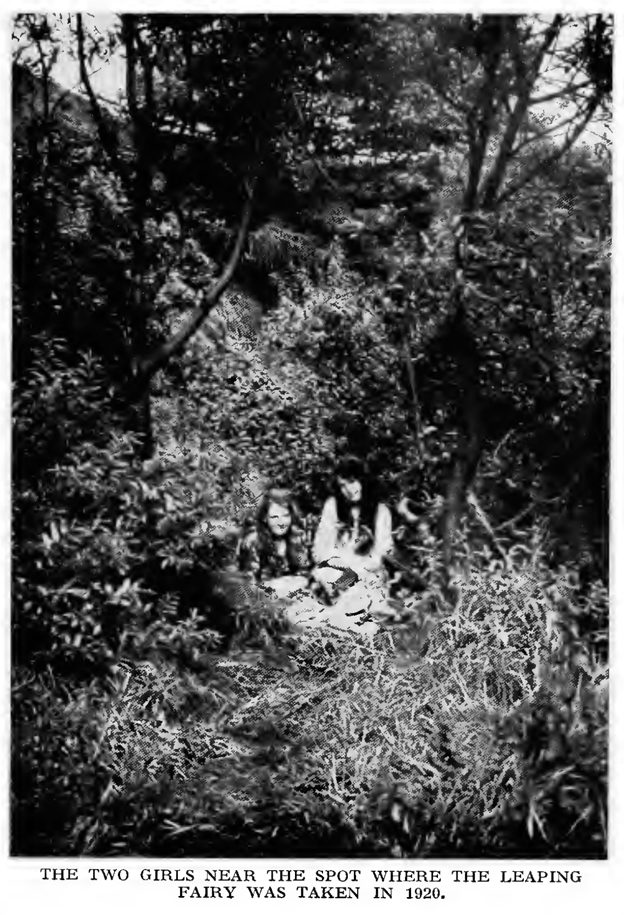

One Saturday afternoon in July 1917, Elsie Wright borrowed her father’s camera and set off with her cousin, returning half an hour later claiming to have photographed a group of fairies they played with in the wood. Elsie, aged 16, and her 9-year-old cousin Frances Griffiths, claimed the magical creatures lived in the woods around the otherwise ordinary Yorkshire village of Cottingley. Elsie’s father treated the photos as a joke, and yet within a year, a large amount of the British public were solid believers in the Cottingley fairies, with the backing of Sherlock Holmes author, Arthur Conan Doyle.

In a letter to a friend from her early childhood in South Africa, Frances included the first and most famous photograph of the Cottingley fairies. The letter, otherwise a typical snapshot of childhood in 1917, describes the approaching end of the First World War, her lessons in French and Geometry, and slightly more unusual– their afternoons spent playing with magical creatures.

Frances and the Leaping Fairy, the third photograph

On the back, Frances captioned the photograph: ‘Elsie and I are very friendly with the beck fairies. Is it funny I never used to see them in Africa. It must be too hot for them there’.

The five photographs of the Cottingley fairies began with Frances and Elsie borrowing her father’s Midg quarter-plate camera. Elsie’s father had set up his own dark room and helped the girls to develop their first photograph. He dismissed the photographic plate that showed Frances playing with the fairies as nothing more than a practical joke. When the girls took a similar photo two months later, this time with Elsie in apparent conversation with a small gnome, he became angry at the girls for tampering with his equipment and confiscated both the camera and photos.

The fourth photograph, Fairy Offering Posy of Harebells to Elsie

However, Elsie’s mother was intrigued by the photographs and took the girls to a lecture on ‘fairy life’ at the Theosophical Society in Bradford. The photos attracted the attention of Edward Gardener, one of the leading members of the society, who saw the photograph as a sign of humanity’s evolution to ‘perfection’, a core belief in theosophy. Gardener was convinced by the first two photographs and urged the girls to take more. The final three photographs were taken as resolute evidence of the Cottingley fairies, and although press coverage was mixed, the photos gathered a large following of believers among the British public.

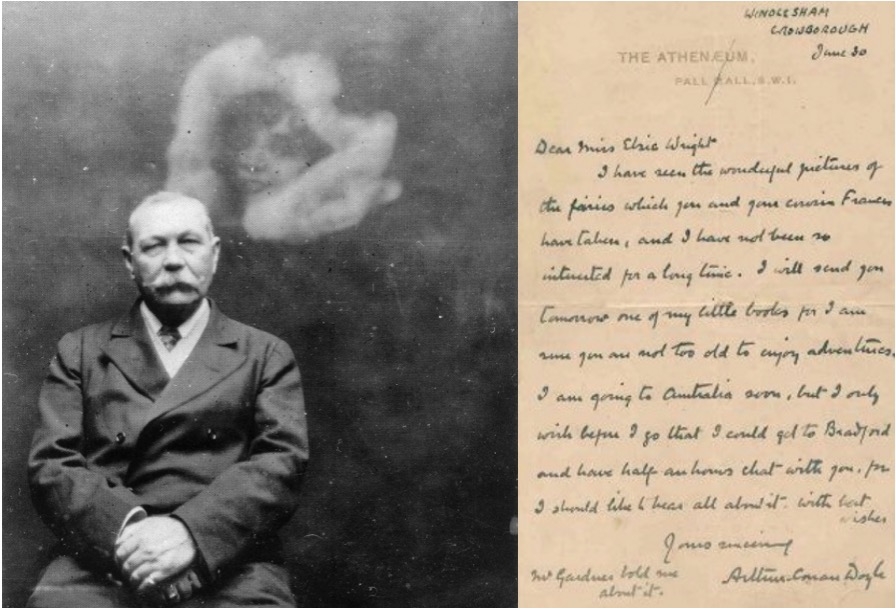

The images were picked up by Arthur Conan Doyle, writer of Sherlock Holmes, physician, and a strong believer in spiritualism. Conan Doyle published the photos as proof of the existence of fairies and gnomes; mythical creatures that he called ‘dwellers at the border’.

‘The Coming of the Fairies’, published 1922, was a collection of fairy sightings around the world that included the fairies of Cottingley beck. Conan Doyle remained a devout believer in Elsie and Frances’ photos, and the ‘dwellers at the border’, until his death in July 1930.

Conan Doyle writes to Elsie about her ‘wonderful pictures of the fairies’, in June 1917.

Skeptics drew attention to the dubious appearance of the fairies, which seemed to be suspended by small strings in some of the photographs. In the second photo, Elsie’s hand is elongated in what Frances argued was ‘camera slant’, and all the creatures seemed to be suspiciously dressed in the latest French fashion.

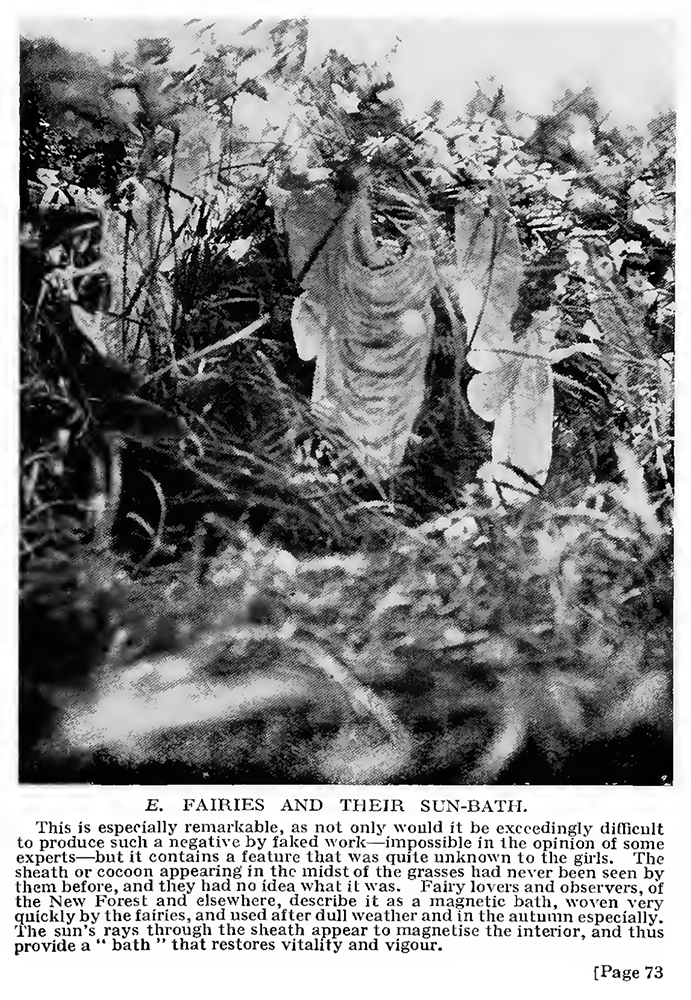

The Fairies and their Sun Bath, the fifth photograph in the series.

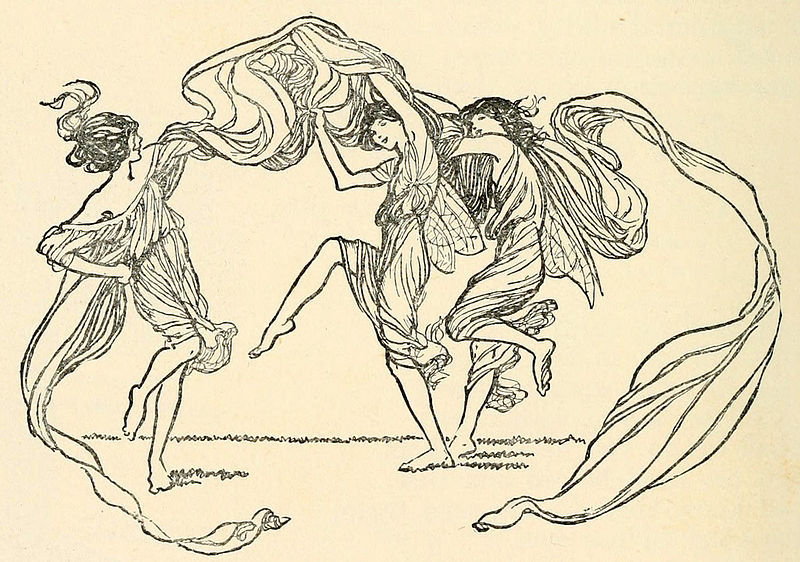

However, it wasn’t until much later– more than 60 years– that the truth about the images came out in the 1980s. In an article for The Unexplained, the girls, who were now elderly women, explained that they had created the appearance of magical creatures using paper sketches, based on Claude Arthur Shepperson’s illustrations in Princess Mary’s Gift Book.

Elsie based the cutouts on Shepperson’s illustrations for Princess Mary’s Gift Book.

Elsie admitted that all five of the photographs had been faked. Frances also admitted to the hoax, but has always maintained that the final photograph was real. Both Elsie and Frances insisted that despite the faked photos there were real fairies around the Cottingley beck, and they used to play with them as children.

So why did it take so long for the Cottingley fairies hoax to be debunked? Many believers were duped simply because they thought the children looked like they were telling the truth. Famous novelist Henry de Vere Stacpool defended the girls by saying, ‘There is an extraordinary thing called Truth which has 10 million faces and forms– it is God’s currency and the cleverest coiner or forger can’t imitate it.’ Except, in the case of Frances and Elsie, they could. It has been speculated that the public were happy to believe the photographs’ legitimacy because it provided a much needed return to innocence during the First World War. In 1917, one year shy of the end of the Great War, the public willingly accepted the story to escape the everyday horrors that usually made up the daily news. Fairies provided a welcome distraction and return to innocence in a time of shocking global violence. Perhaps Elsie and Frances’ photographs, and the idea of harmless ‘dwellers at the border’, was simply what the public needed most at this time.

By Dido Gompertz