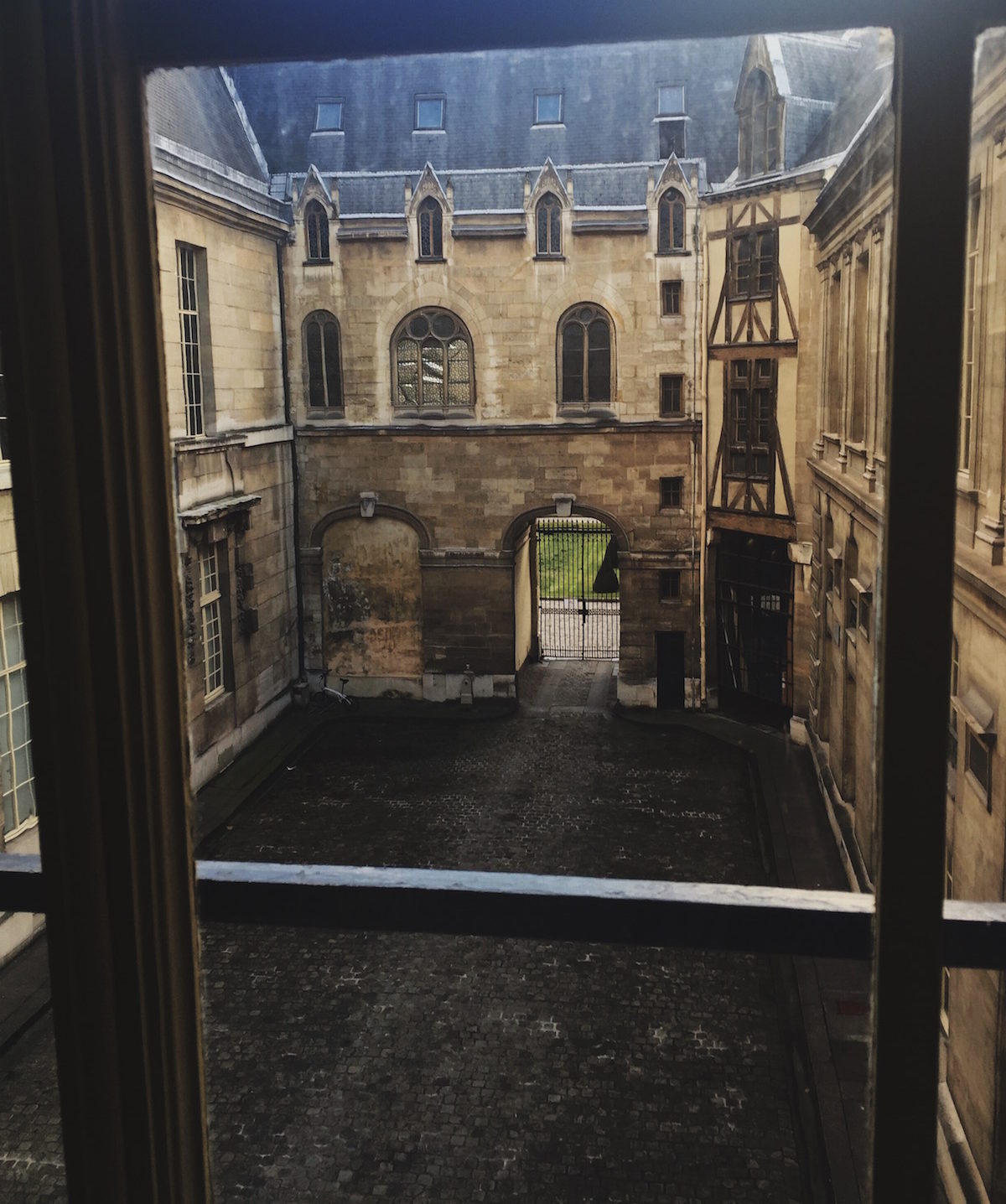

Guarded by a fortress of medieval walls cut from thick ominous sandstone, Les Archives Nationales means business. The former humble abode to a member of the French aristocracy, today this decadent sprawling chateau houses France’s most precious documents, each securely locked behind layers of mahogany-framed, etched-glass bookshelves.

Formerly bequeathed the title “Hôtel de Soubise,” the fortified compound boasts an intriguing and scandalous past. Presently housing an assortment of treasures, it is rumoured that the château’s initial renovation was funded by King Louis XIV as it was then occupied by his mistress, Anne de Roman-Chabot, favoured protagonist of the aristocracy’s haughty whispers regarding the King’s romantic affairs.

The elaborate gilded mouldings suffocating the walls, interrupted only by massive pane-glass windows, are an exhibition of the nation’s innovative superiority, reminiscent of Versailles. However, interestingly, the identity of this extravagant panelled stage-set is no longer know as the Hôtel de Soubise today, because like all other aristocratic estates, it fell victim to the revolution’s brutal destruction of hierarchical superiority. Thus these walls now serve as a whimsical imagination of what might have been, a collage of materials extracted from the many warehouses that stored the royal-court’s out-of-season garnishes.

Public access to the archives is entirely ~interdit~ permission granted only to those whose intellect and will can endure the extensive research application process. Luckily, I strolled into the pristinely preserved space alongside a decorated art historian, one specialising in the surreal and concocted universe of Versailles.

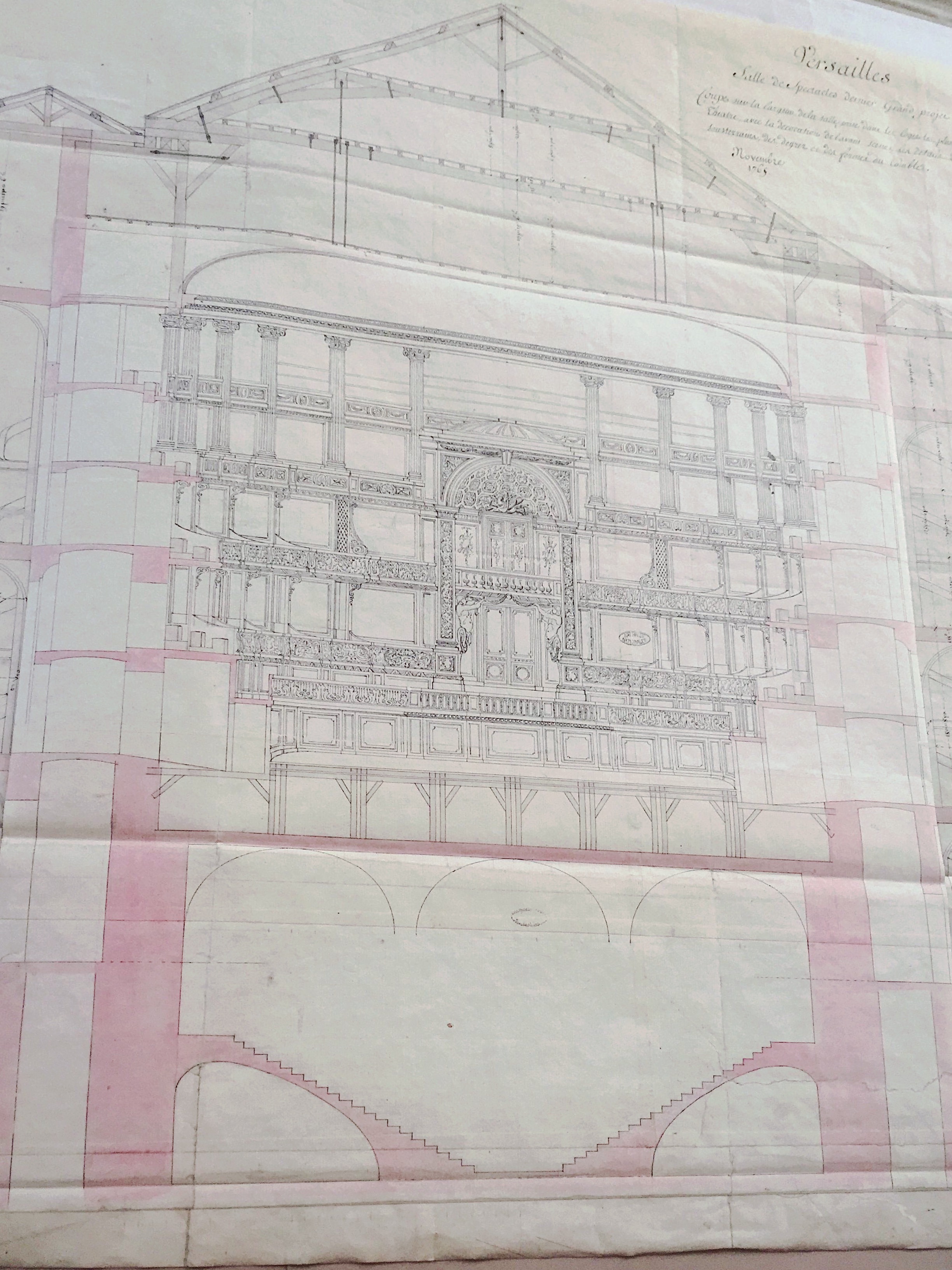

Diving headfirst into the Nation’s coveted treasure trove, I inspected original 400 year-old architectural blueprints that detailed the many phases and facets of Versailles, separated from the diaphanous drafting papers only by the thin blue waxy plastic of our gloves. The prints of architects le Vau, le Notre and Braun were magnificent works of art in their own right, detailing every wood moulding and etched marble via the elegant fluid lines of a quill pen.

Many a times had I had scurried across Versailles’s glistening uneven cobble stones once traversed by Louis XIV’s hunting dogs, the woman famed for the phrase “let them eat cake” and let’s not forget the revolutionary forces. Now I was carefully studying the pristine reproductions of Versaille’s Royal Opéra; its’ hand-painted marble balconies, gold-gated boxes and velvet smothered seats. The seating chart, prescribed with the names of the most powerful and enviable Parisians of the 17th century, represented one of the most forceful and blatant parades of social hierarchy within the royal court. The true spectacle of course derived from the audience, the recital a mere accessory.

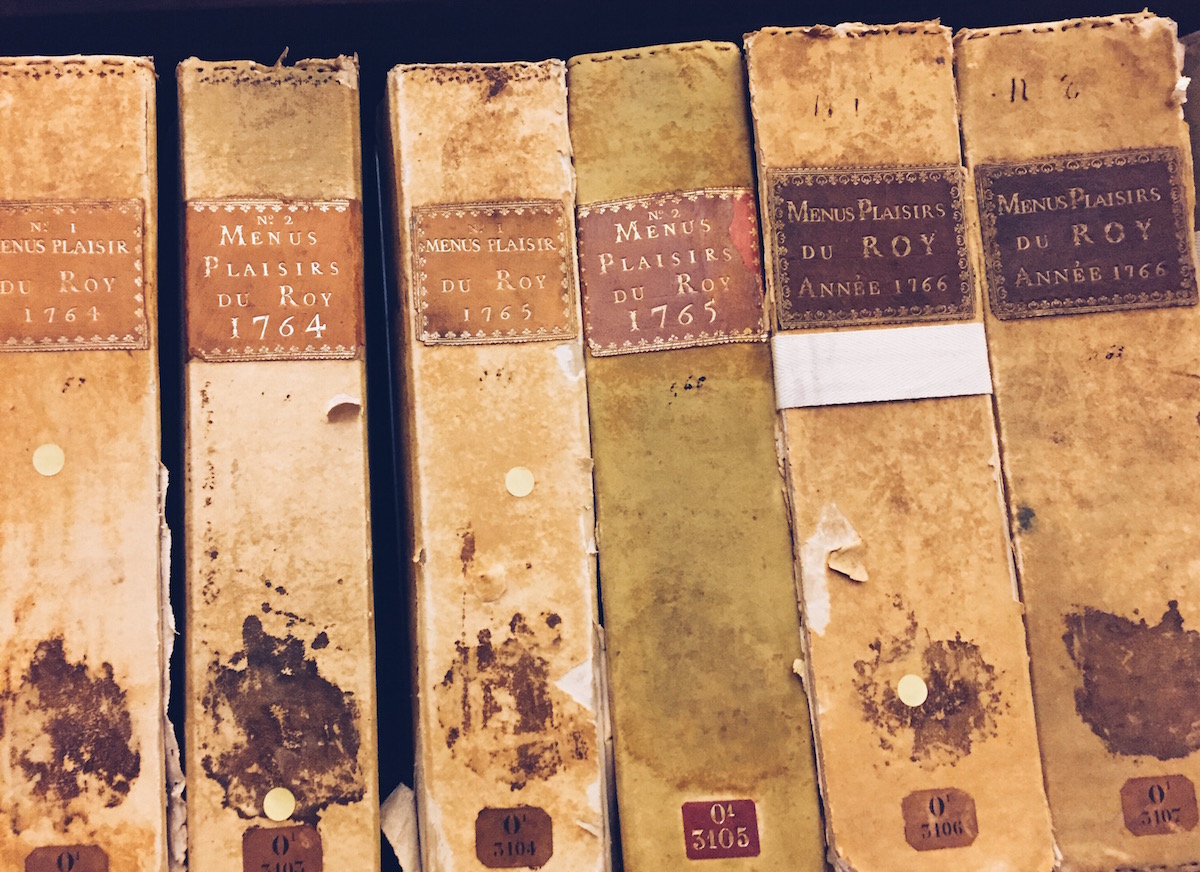

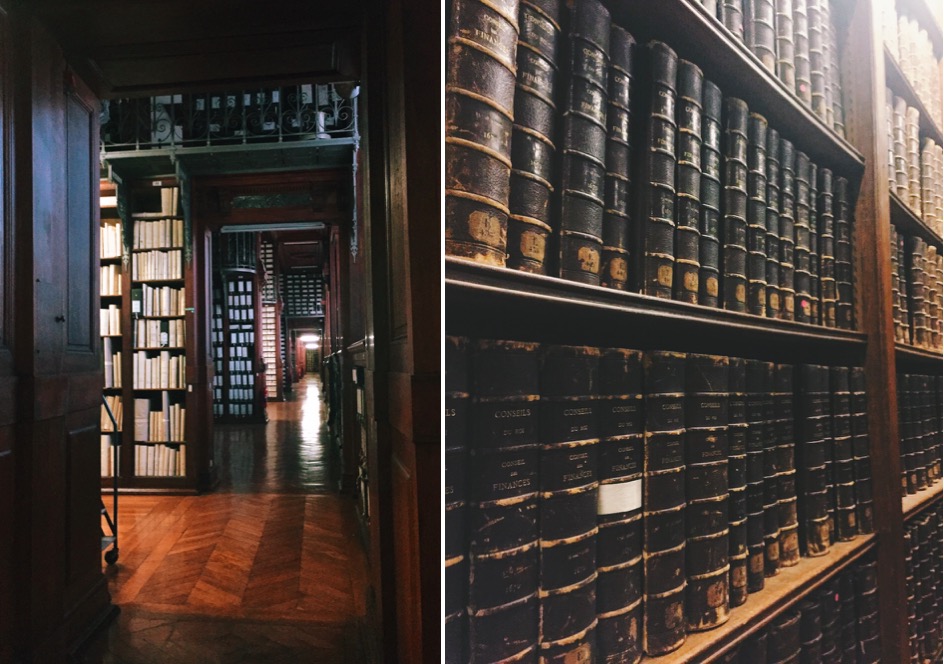

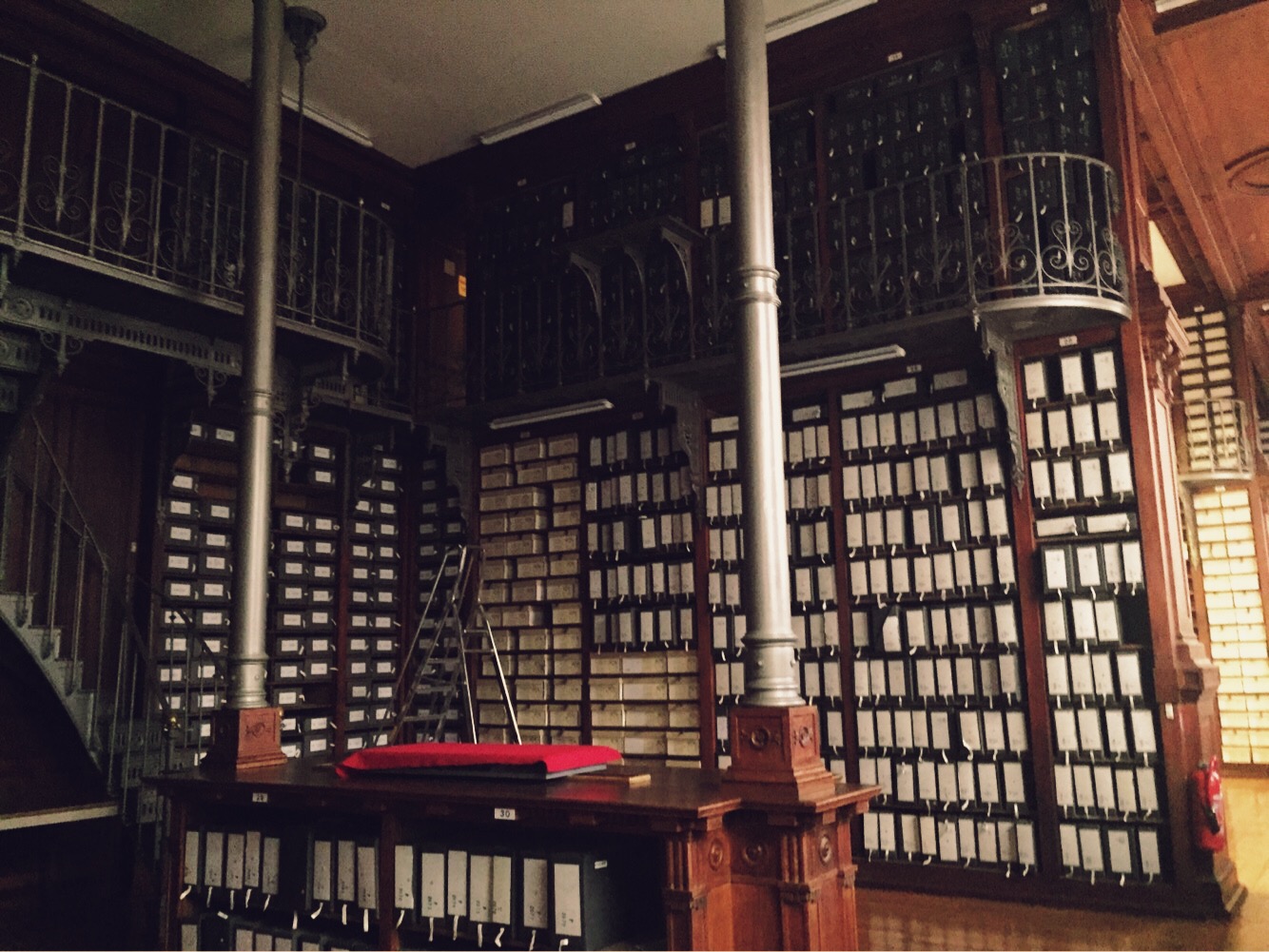

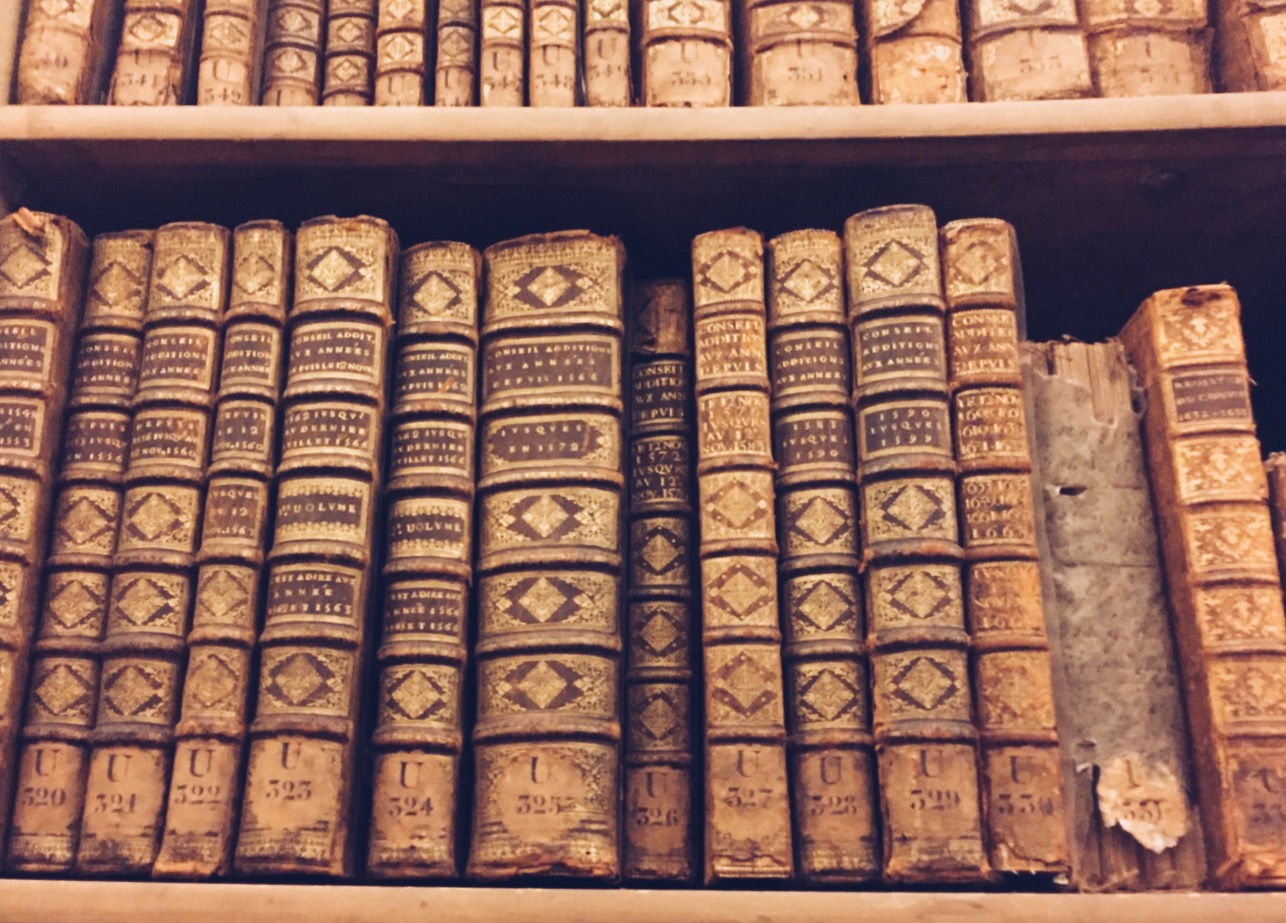

My rare access to the never-ending tunnels of original books, logs and manuscripts dating back to the Royal court, books marked with the simple symbol ‘0’ indicating the Ancien Regime, was truly extraordinary. Every room is filled floor to ceiling with dusty books and catalogues, each in their original crackled leather binding, and stuffed with thick handmade paper exhibiting characteristic uneven edges.

The first few rooms overflow with volumes dedicated to the royal domain’s expenditures, an archival tradition initiated by Louis XIV’s esteemed Minister of Finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, famous for bringing the economy back from the brink of bankruptcy, his name meticulously etched into the thick leather spines, illuminated with melted gold ink. Each of these heavy catalogues are dedicated to a specific time period, some detailing only a short week of festivals, soirées and renovations, others dedicated to months of less extravagant and more ‘peasant-like’ activities.

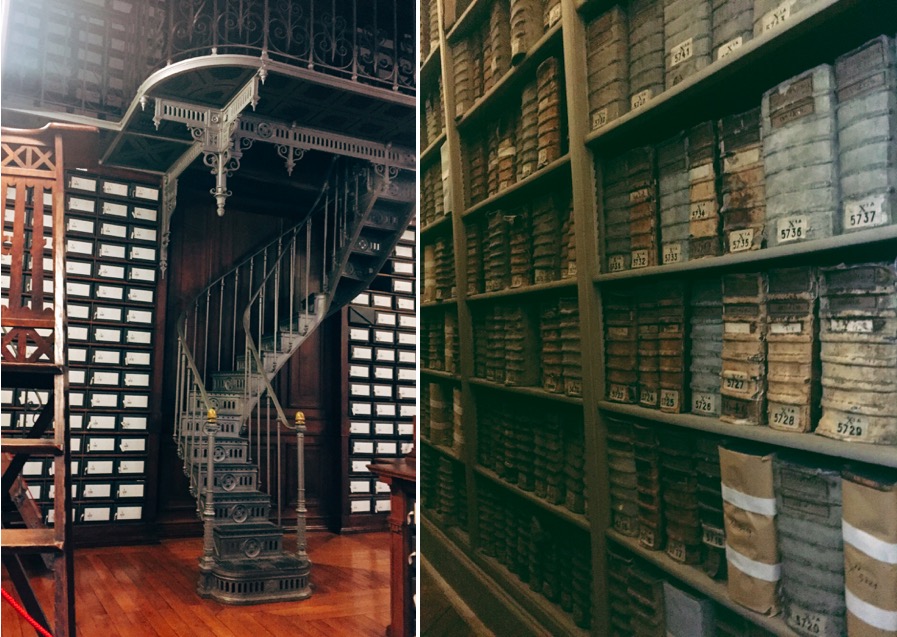

Each space is shaded in rich brown wooden hues with winding wrought iron spiral staircases that lead to wrap-around balconies punctured by rounded doorways and views to an infinite cascade of identical spaces. The air held captive between the massive but delicate bookcases is weighted by a melancholic beauty, one implied by the stagnation of time. Breaking the archive’s principle rule with the aid of a mischievous Frenchman, I cracked open the King’s most precious class of manuscript – “Les Menus Plaisirs du Roi” in which the extravagant sensory experience accompanying each royal party is curated. I marvelled over the minute scribblings that outline every sumptuous detail of the grand event, preoccupations that served as the definition of so many subjects’ lives. It’s impossible to absorb the incredible complexity contained within a single page and, even more, to recognise that the infinite knowledge replicated throughout the archives serves at the foundation for our presumptuous knowledge of this past– mere abbreviations of the multifaceted world kept alive in this building.

The archives served as a vehicle to trespass upon the forgotten days, months, years and lives of past eras and centuries: a romantic time capsule securely guarding the nation’s precious secrets.

By Noa Matia Wolff-Fineout