© James Castle Collection and Archive

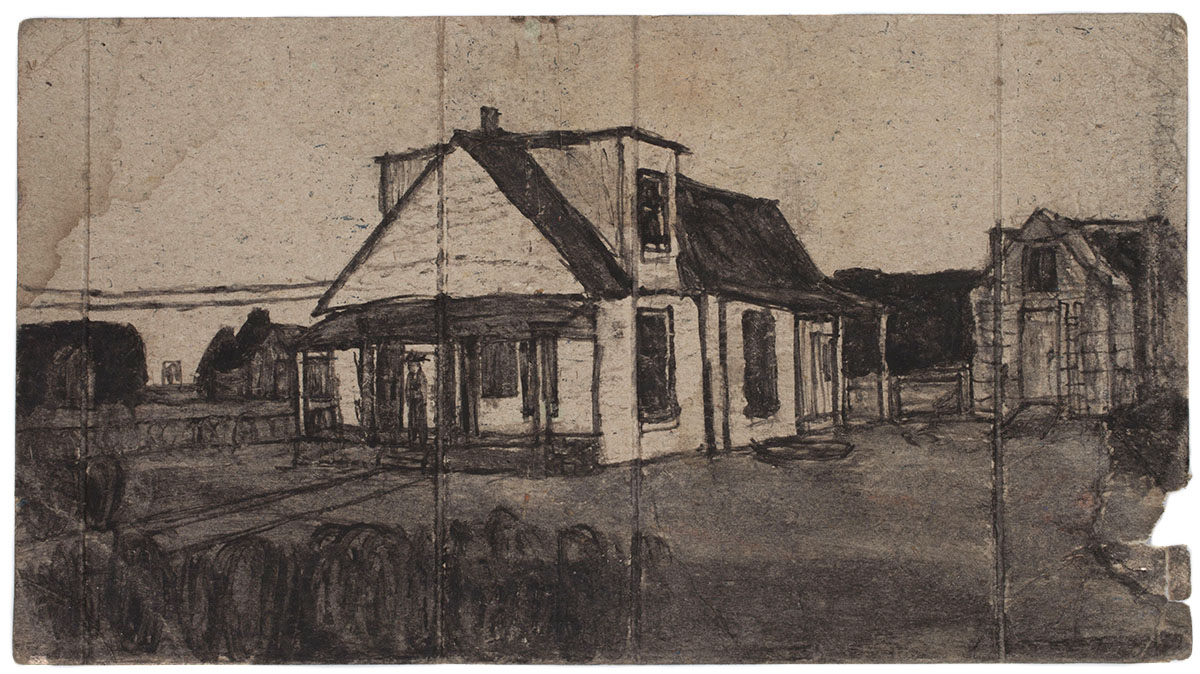

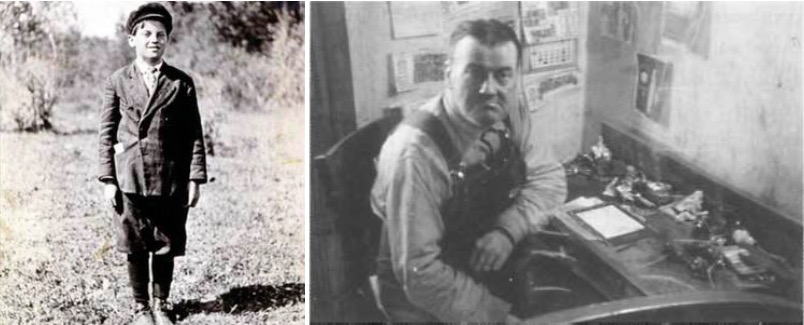

James Castle was born profoundly deaf, and never learnt to communicate through sign language or writing. He used make-shift materials, including paper scraps, soot and his own spit to craft sketchbooks and draw his surroundings; an isolated community in Idaho with more cows than people. And yet, James Castle’s view of the world is entirely captivating. Born in the last few days of the 19th century, from a very young age, James’ work ran remarkably parallel to the development of 20th-century art history, unbeknownst to his own family, let alone to the art world. Despite attending a special school for the deaf and blind for five years, the institution only taught an oral method of communication and his family wasn’t able to teach him how to sign. His drawings, therefore, became his only form of expression, and to discover James Castle’s art is to step inside the mind of one very curious and misunderstood individual….

© James Castle Collection and Archive

© James Castle Collection and Archive

© James Castle Collection and Archive

© James Castle Collection and Archive

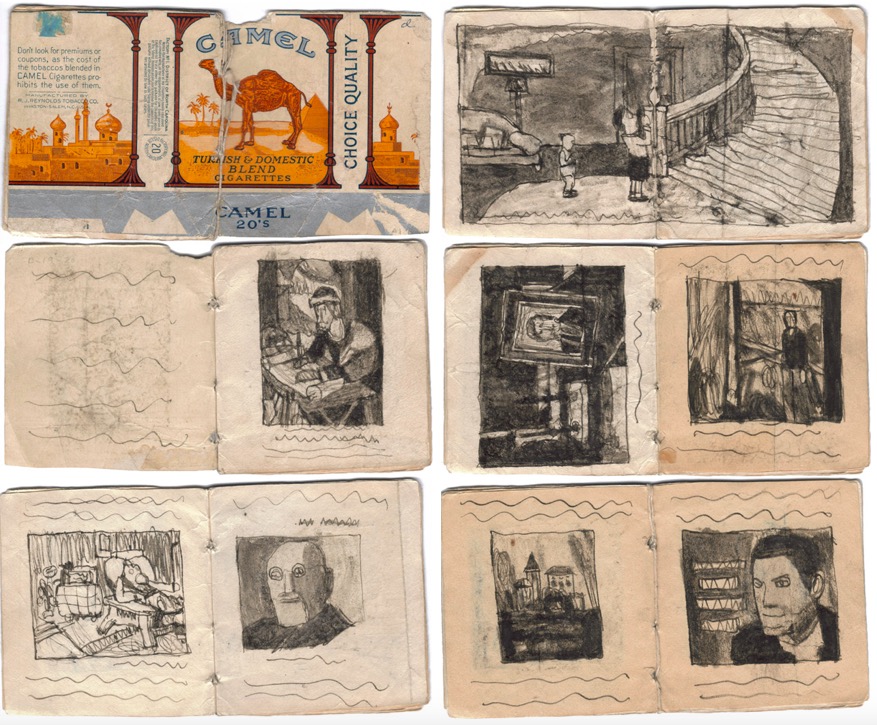

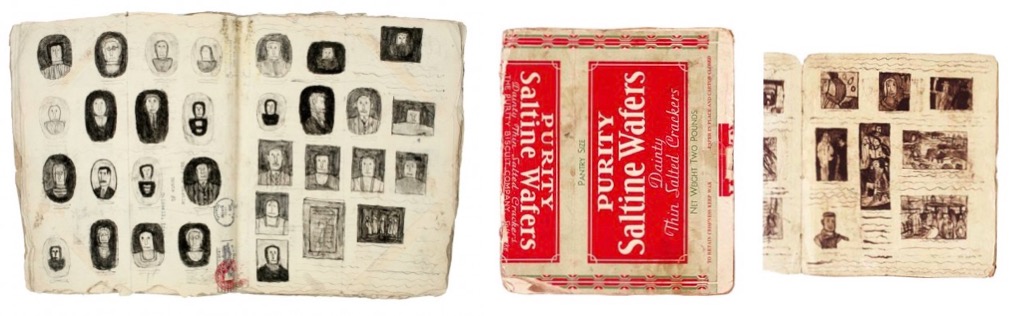

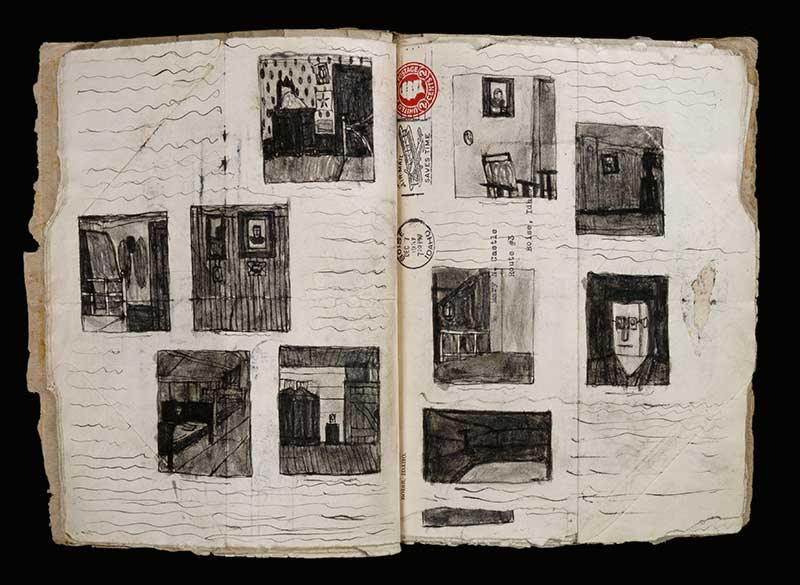

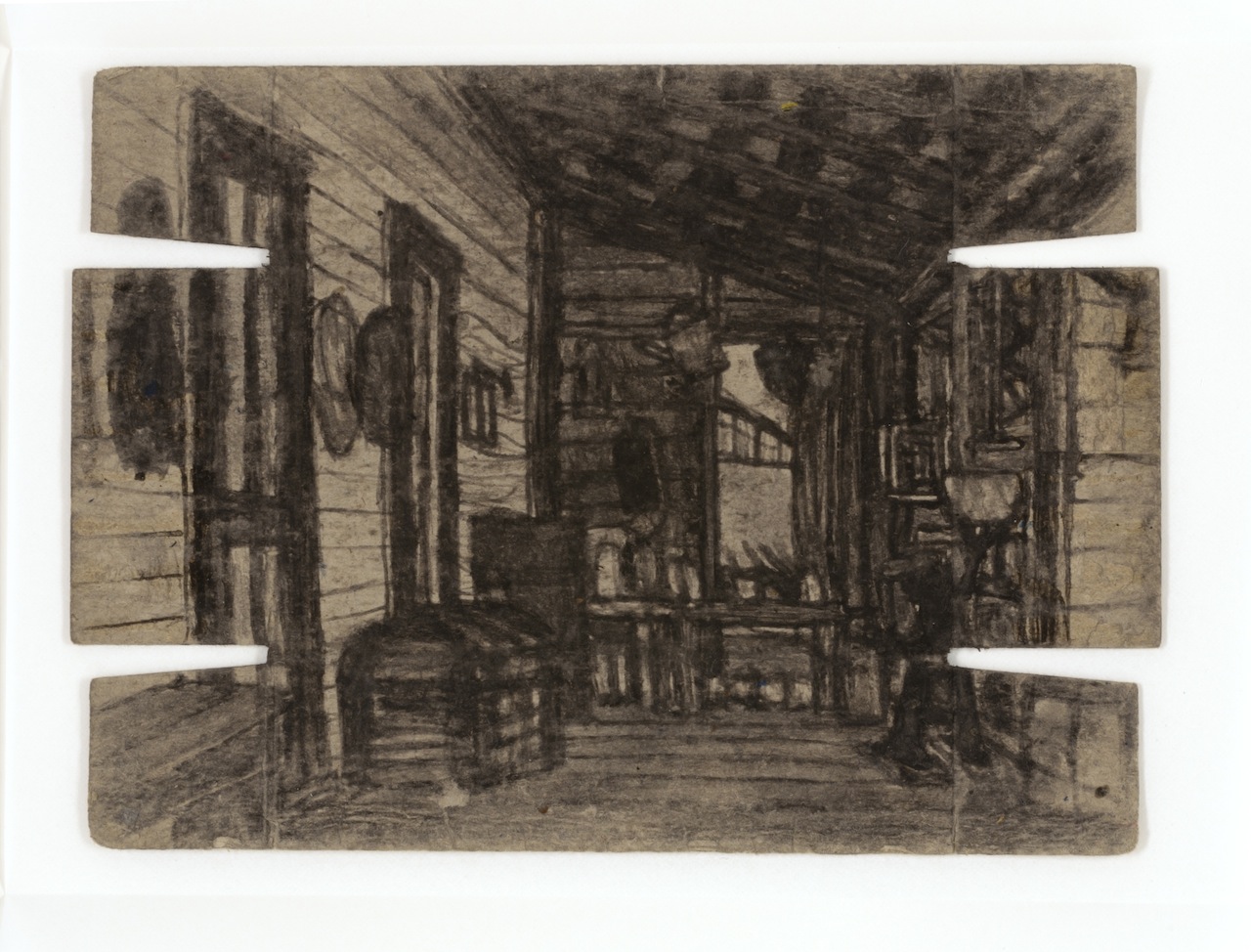

Castle’s parents ran a general store from the living room of their family home, and from childhood, he used found materials to create drawings, paintings and collage. He used spare stock including matchbooks, receipts, and grocery cartoons in his creations. These crudely made creations today, are sought after works collected by major institutions all over the world, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the National Arts Museum in Madrid, the Venice Biennale exhibition, the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

© James Castle Collection and Archive

© James Castle Collection and Archive

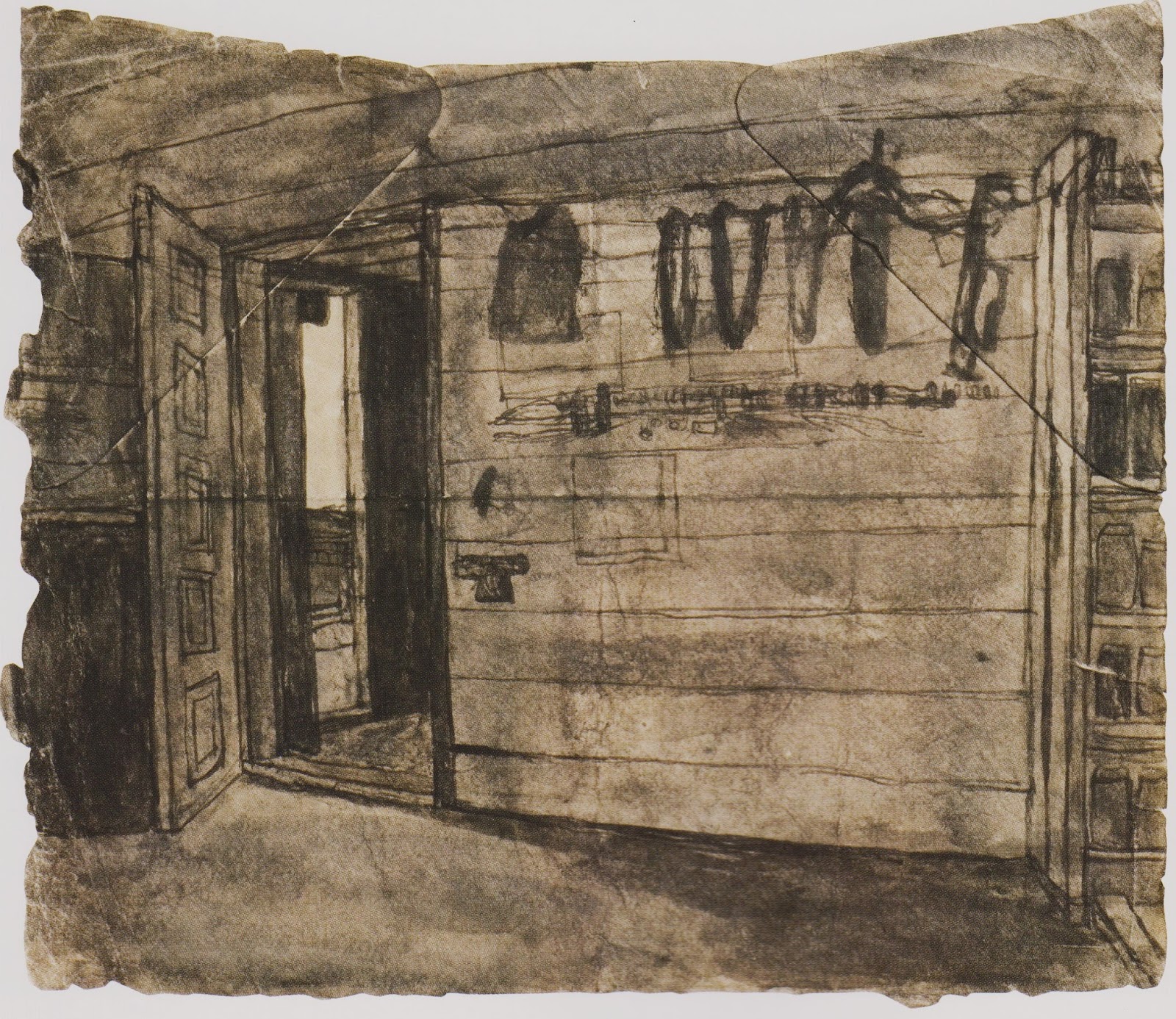

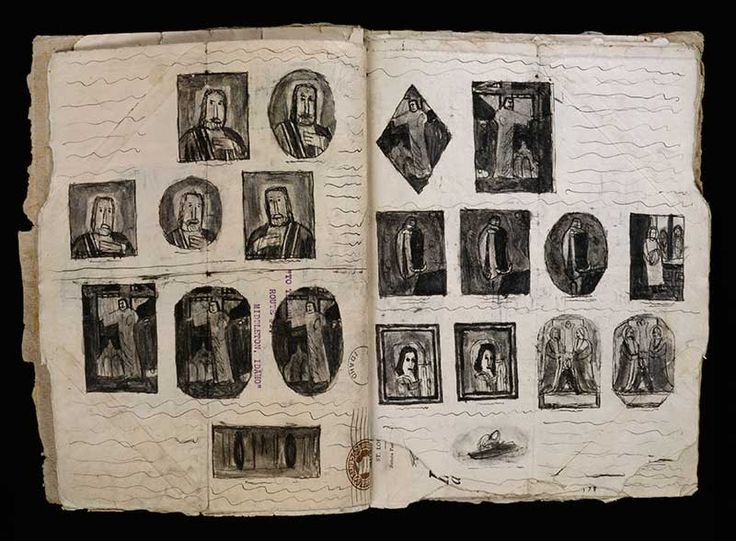

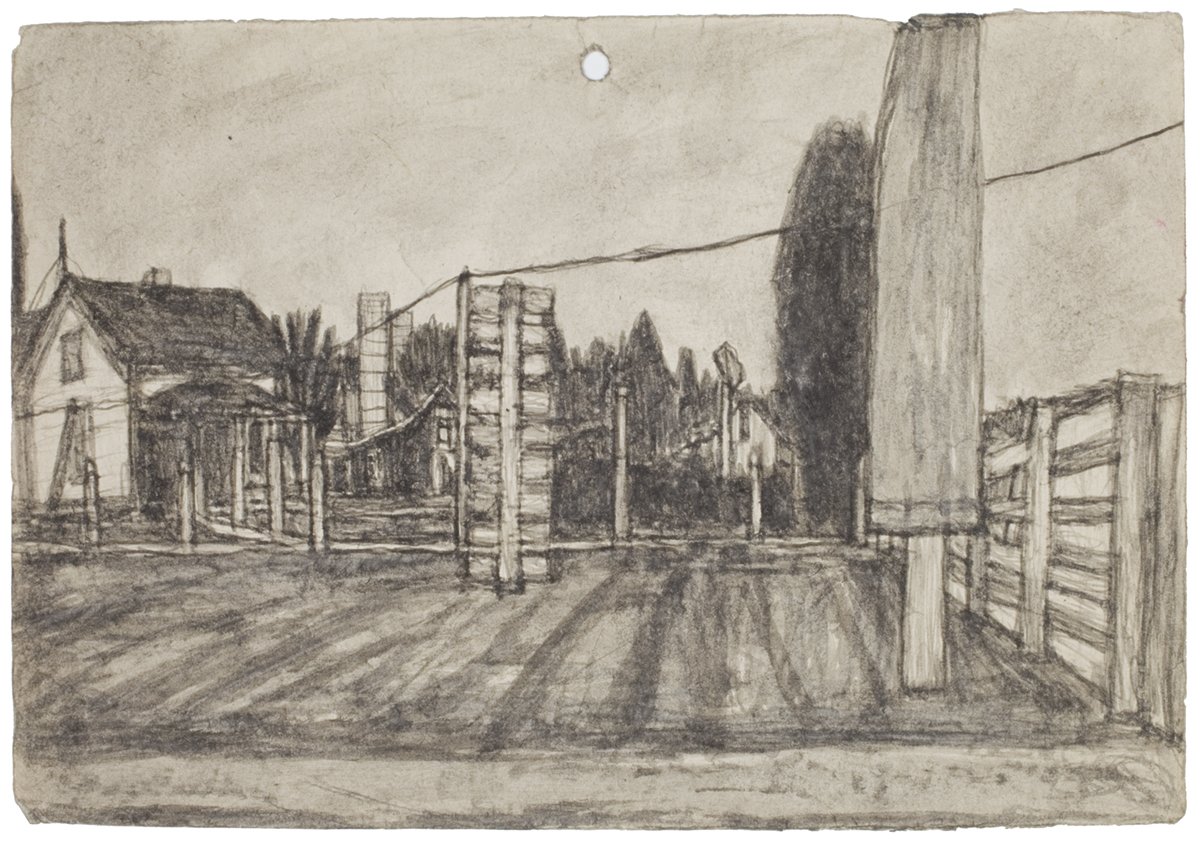

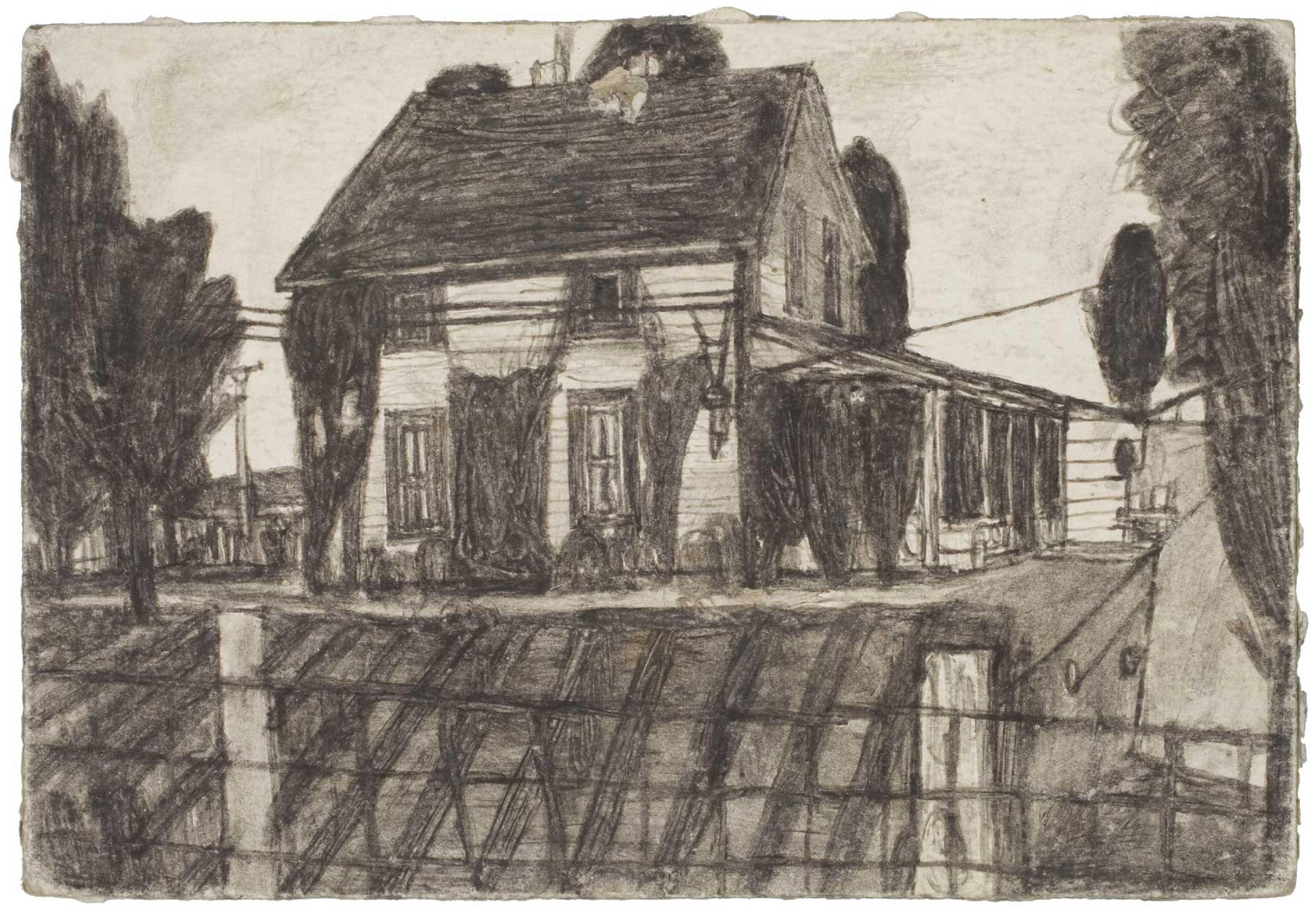

He sourced paper (and inspiration) from leftover packaging or post – his father was also the postmaster – and created ink by combining soot from his wood-stove with his own saliva. Instead of paintbrushes, Castle applied his ink with sharpened sticks or other found objects from the community. Family members gave him oil sticks and watercolours, which meant he could paint with colour.

via Artsy

© James Castle Collection and Archive

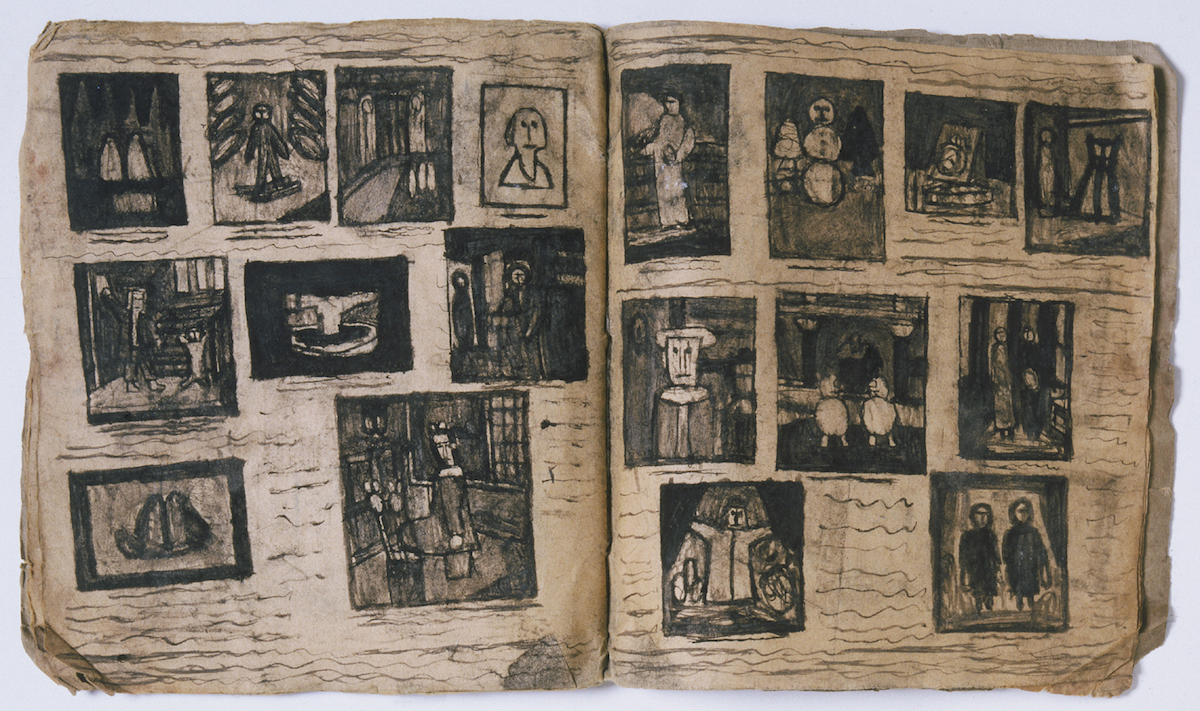

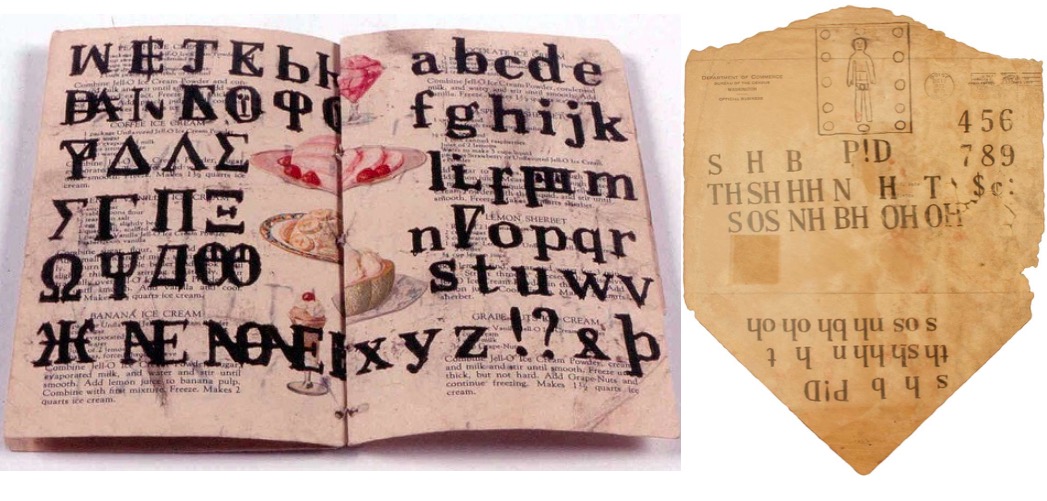

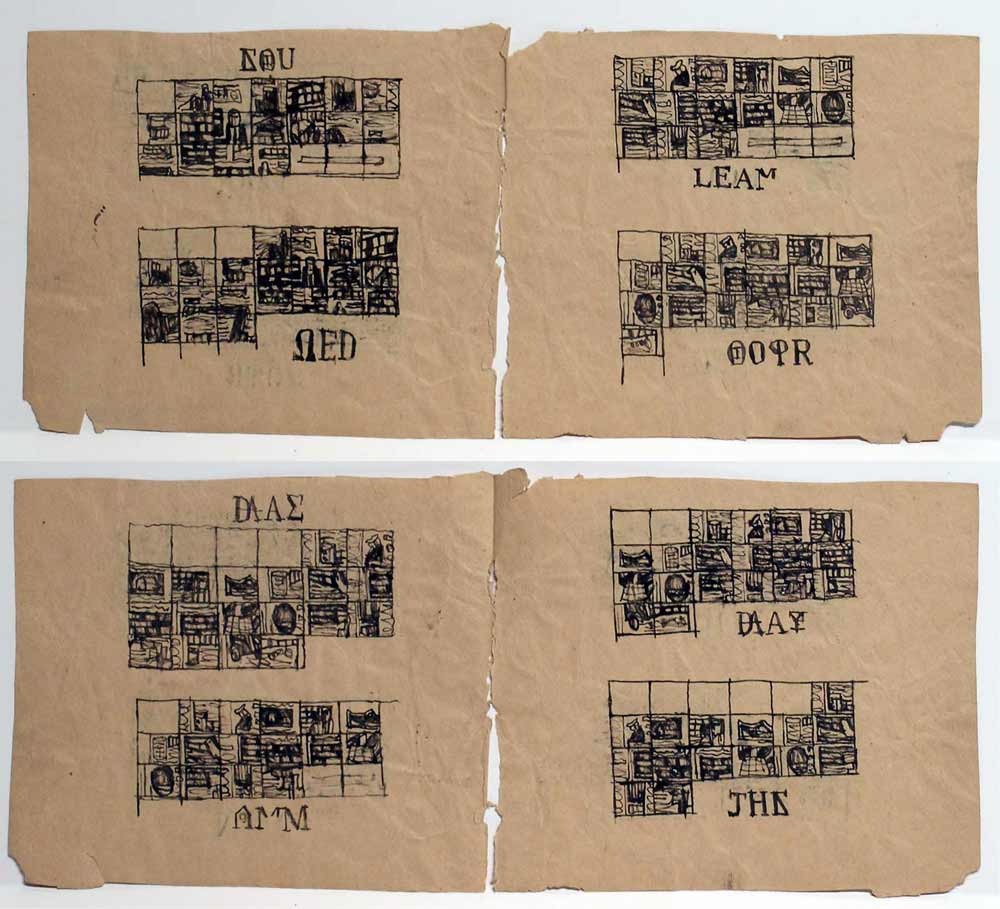

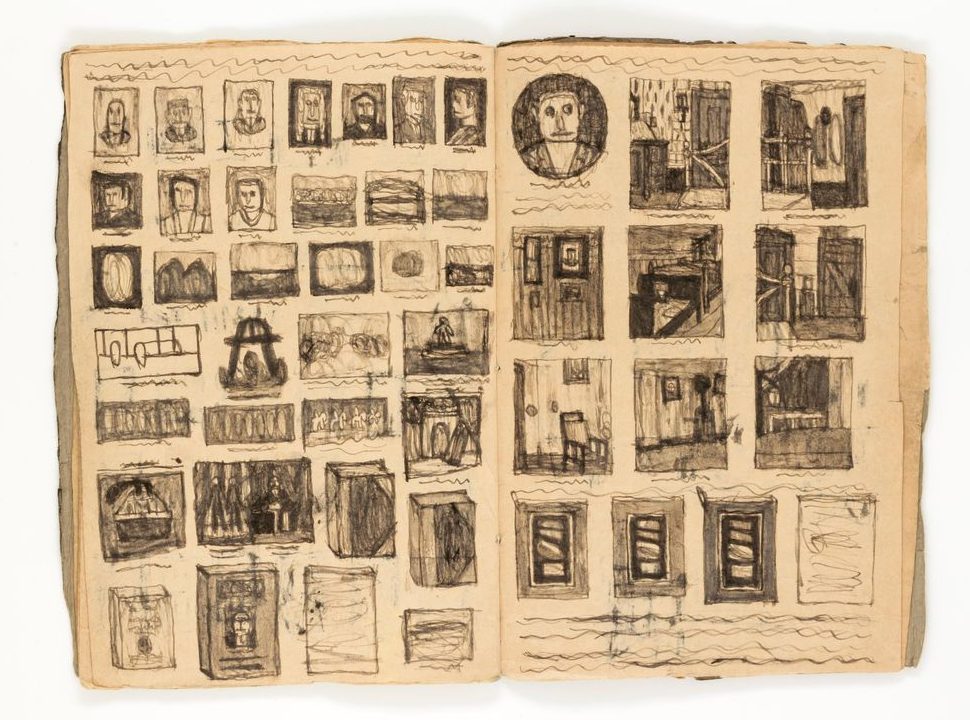

His booklets are laid out like a regular book or photo album, with imitation text accompanying his pictures. While Castle never properly learnt any form of communication, the layout of his booklets shows an attraction to written language.

© James Castle Collection and Archive

Even though he did not put words together, he frequently made crisp, exact copies of individual letters, alphabets, slogans and headlines. This desire to communicate is probably what caused Castle to produce such a huge volume of art.

© James Castle Collection and Archive

There are also symbols throughout, which Castle might have picked up from the other students at the Gooding School, who often taught each other sign language in secret.

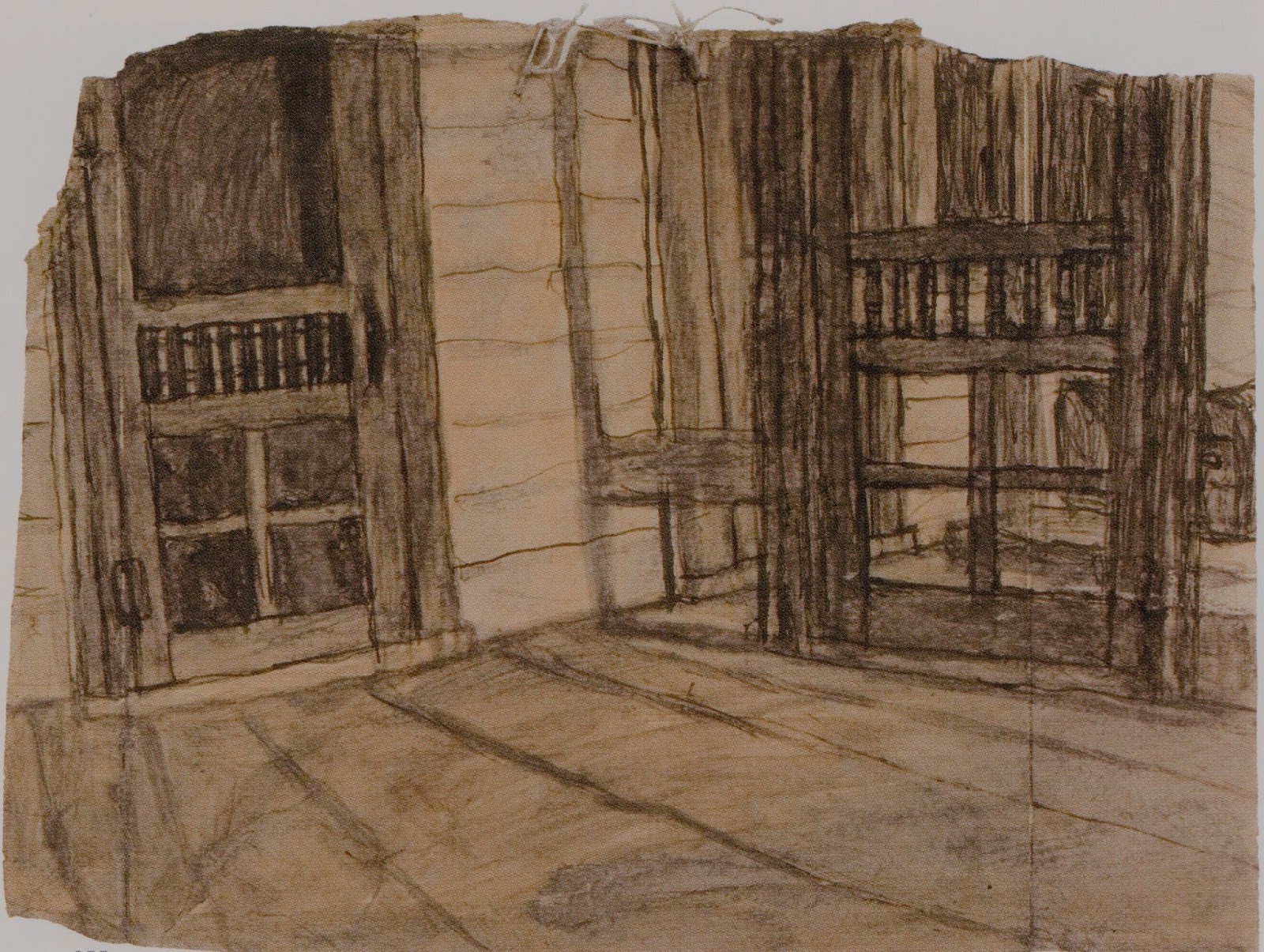

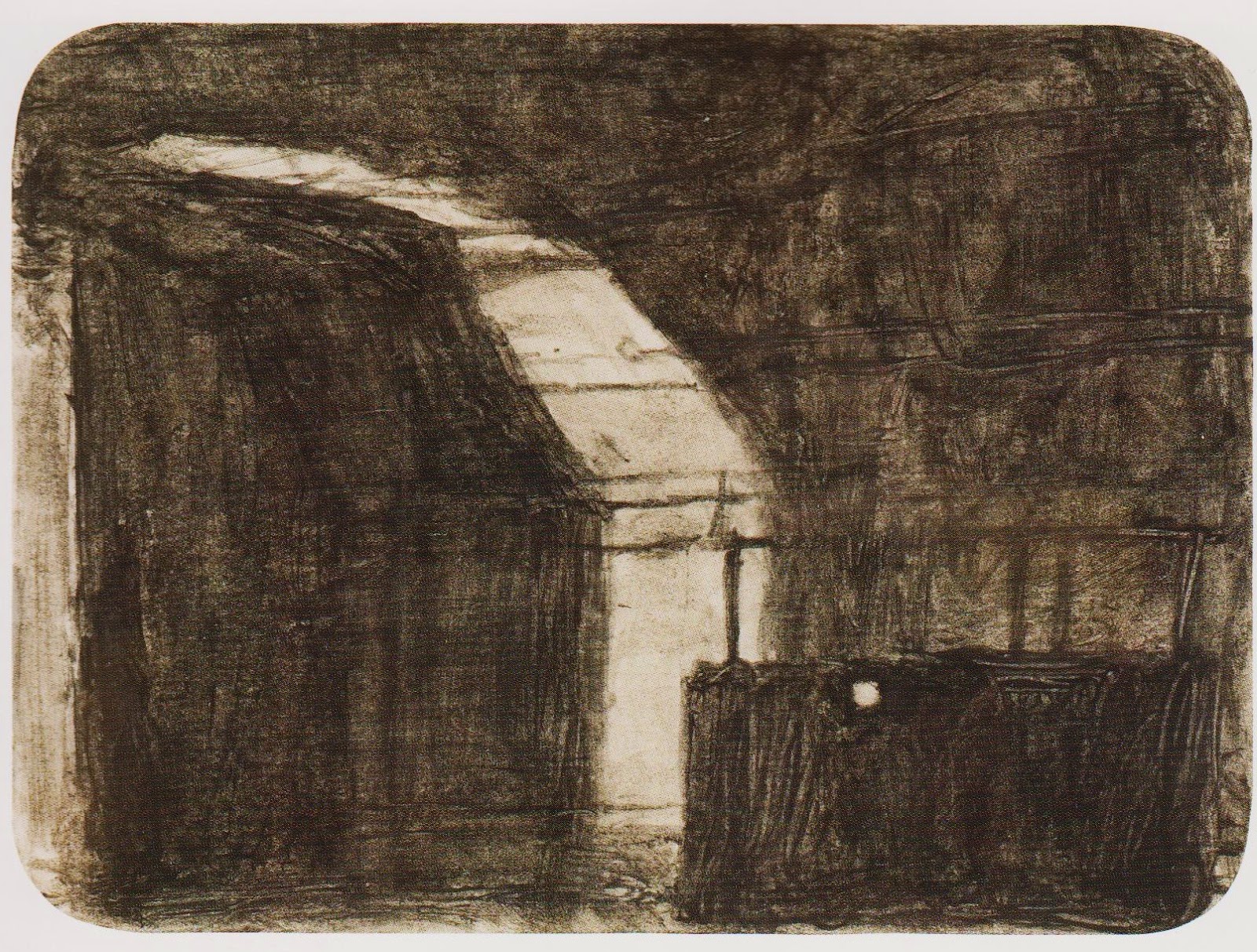

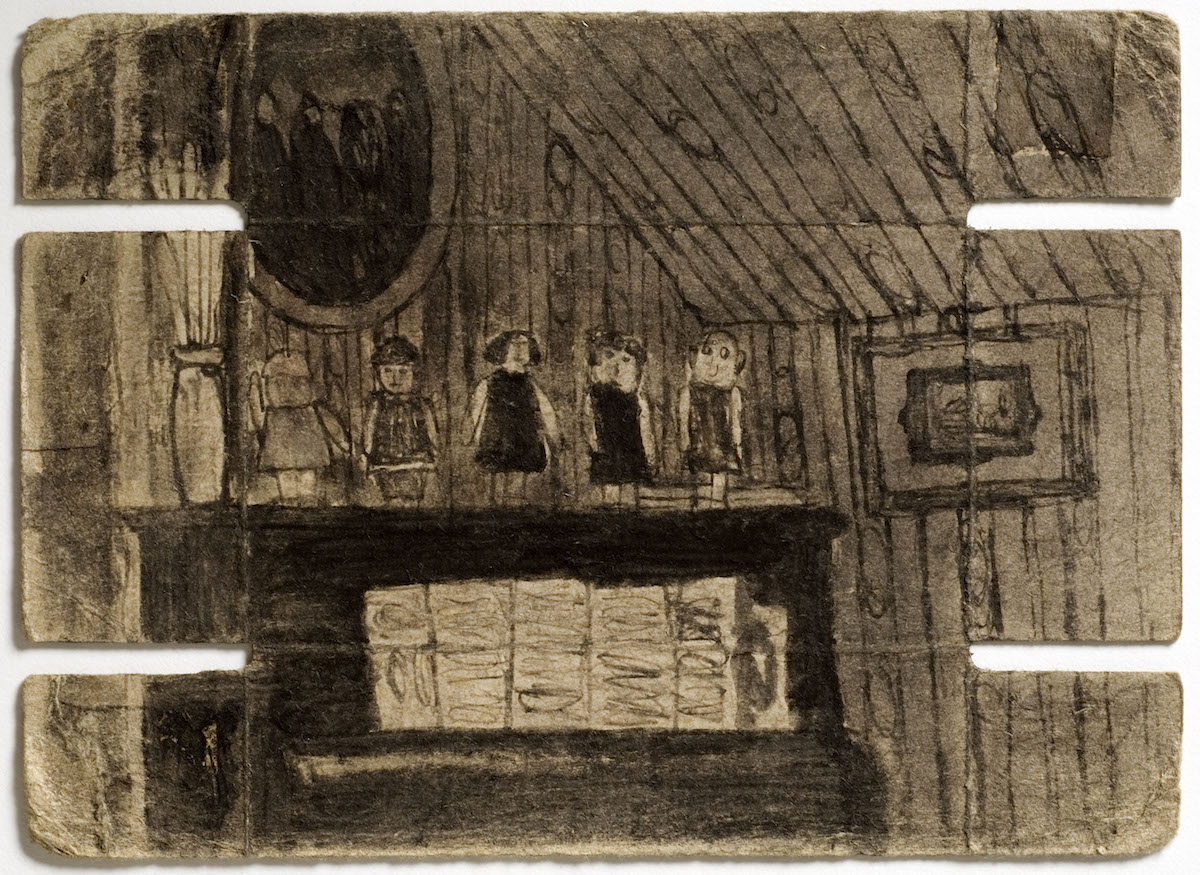

A shaft of light running down the angles of an attic ceiling and wall could appear both in a handmade book and as a stand-alone drawing.

The meaning behind Castle’s symbols remains a mystery and adds to the haunting idea that, despite his hometown’s close-knit community, James lived his life very much alone.

He presented the bulk of his work in these handmade books, which he stored in every nook and cranny throughout his family home. It wasn’t until the 1950s that Castle’s nephew, Bob Beach, suggested the booklets were more than just clutter. Beach took some of his uncle’s work to the Museum Art School in Portland, Oregon, where he was a student. From there, Castle’s work – all listed as “Untitled” – captured the imagination of many artists and was exhibited across the region. Castle himself never ventured very far from his community in Garden Valley.

© James Castle Collection and Archive

© James Castle Collection and Archive

© James Castle Collection and Archive

© James Castle Collection and Archive

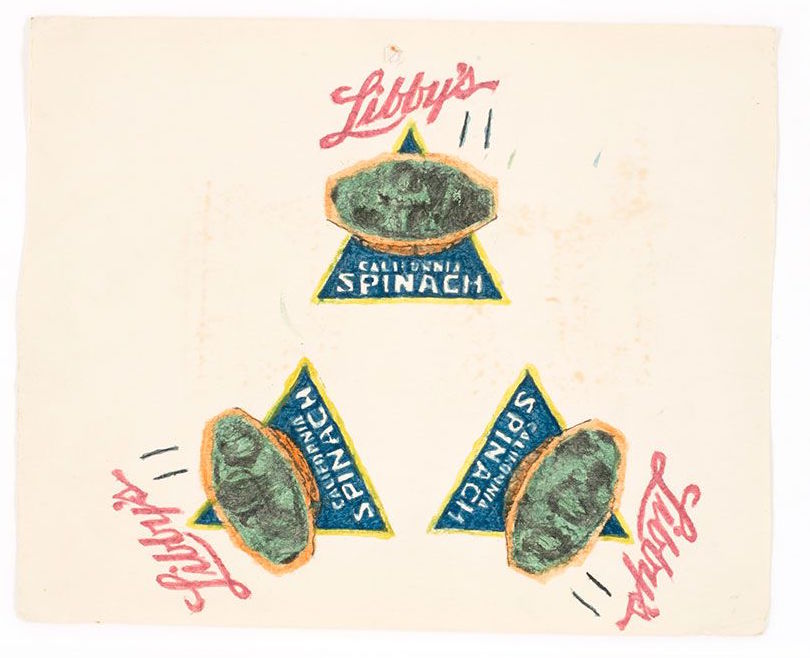

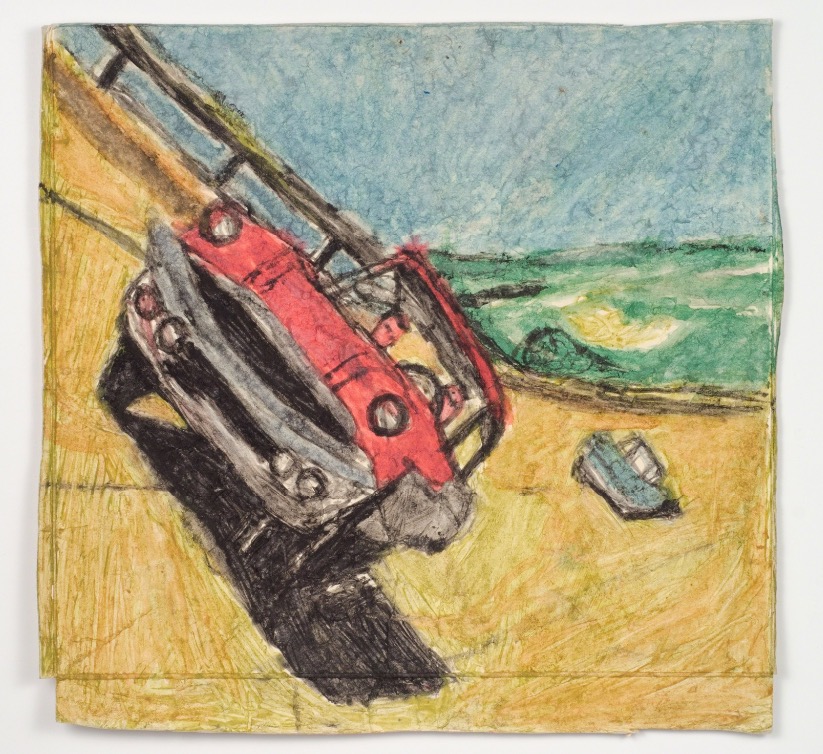

From the materials used, the subjects captured and the circumstances in which they were created, Castle’s booklets are a perfect preservation of his era. The Western frontier was still being settled, and the impact of machinery just being felt. Castle used the logos of old cans like Libby’s Spinach, or Lucky Strike cigarette boxes. These symbols of old Americana provide the backbone to his own illustrations, which document his surroundings and daily routine. There isn’t a part of Castle’s work that seems out of place. The booklets are like little relics, showing the life of James Castle, his family and friends.

© James Castle Collection and Archive

Castle documented everyday phenomena in an almost childlike approach to art, which seems to focus on discovering and understanding the world around him. In this way, Castle’s art was a corridor to the outside world; a way for him to understand, and be understood. The careful thought that was given to every page gives them a nuance that makes each little picture worth looking at.

© James Castle Collection and Archive

Castle kept working until his death in 1977, aged 70. Overwhelmed by the attention, his family denied all access to the collection for 20 years, but they have recently started sharing some of his booklets and paintings. In 2015, the Smithsonian American Art Museum opened one of the largest collections of Castle’s pieces with a retrospective called, “Untitled: The Art of James Castle.” The Smithsonian’s director Betsy Brown spoke about her admiration for Castle in a statement about the exhibition. “James Castle’s drawings and paintings confirm that art offers a fundamental way to know ourselves.

© James Castle Collection and Archive

He worked for decades in the rural west, surrounded by family but with little experience beyond his community and with no formal art training. But his discerning eye found subjects all around, creating an extended portrait of his world.”

Perhaps it is because Castle was unable to communicate through writing or speech in the traditional sense that his drawings have a unique sensitivity. Or perhaps it was his position in time, and a desire to preserve traditional rural America while facing a new and modern age. Whatever the reason, it’s an honour to peek into Castle’s quiet world through the images he painstakingly created. Despite making his booklets a century ago, James Castle remains relevant today for his modest, beautiful view of a changing world.

By Dido Gompertz