© Luke J Spencer

There is a bank in Lower Manhattan with a peculiar secret. The Citibank occupying the prestigious address of Number One, Broadway, looks like a normal enough bank branch, until you look closely at the two entrances. One doorway, leading to the ATM, has an ornately carved stone frame saying ‘First Class’. The other, leading to the bank lobby itself, is marked with the slightly less grand sounding ‘Cabin Class.’ For this bank was once the ticketing office of J.P. Morgan’s vast shipping empire. An empire that included the White Star Line, and its most iconic ship, the RMS Titanic.

© Can Pac Swire

If the Titanic had ever made a return voyage to England, this is where you would have come to buy your tickets. Either entering through the doors marked ‘Cabin’, or, if you were more fortunate, the ones marked ‘First’. The unusual bank doorways are mostly overlooked by the tens of thousands of visitors who flock to Lower Manhattan everyday, whether sailing to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, or visiting some of New York’s most iconic landmarks such as Wall Street and Di Modica’s Charging Bull sculpture.

City Bank Farmers Trust Building © Luke J Spencer

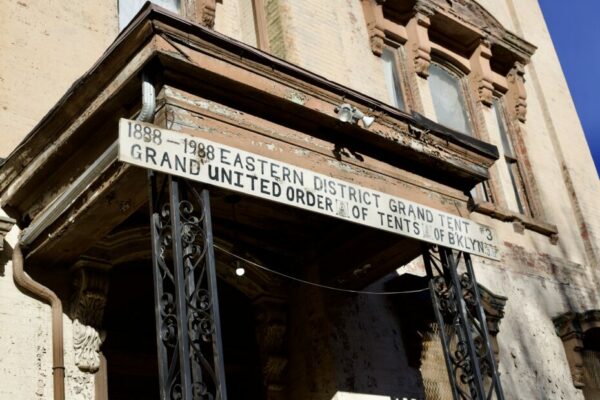

Hidden away throughout the Financial District, are many other forgotten traces from a bygone era, the golden age of steamship travel…

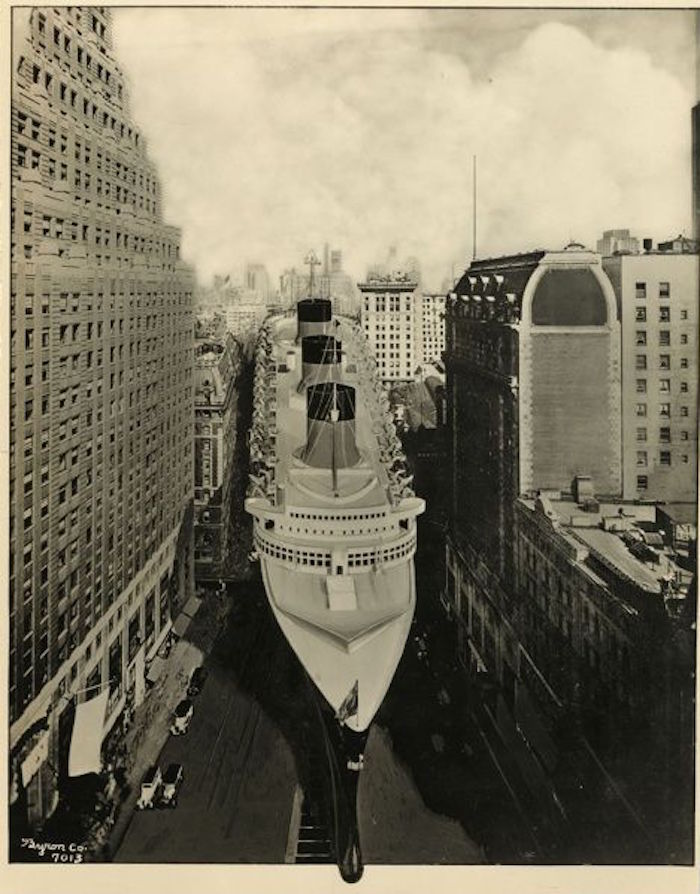

Promotional photograph of the SS Normandie superimposed on New York City streets, photograph by Byron Co., 1934

© Luke J Spencer

The bank at Number One, Broadway was just the start of a block, which was informally once known as ‘Steamship Row’. This suitably grand street of imposing skyscrapers housed the offices and ticketing halls of the juggernauts of ocean liner companies.

Passengers aboard the Queen Mary during the ship’s heyday

This was the glamorous era of ocean travel, of floating palaces racing across the Atlantic, bedecked with grand ballrooms and opulent state rooms above, and thousands of immigrants securing passage to the New World in steerage below.

It’s hard to picture today, but New York was once one of the world’s busiest ports. “A city of hurried and sparkling waters, city of spires and masts”, wrote Walt Whitman in Manhattan. The 19th century slips and quays of the South Street Seaport, densely packed with tall masted sailing ships, soon gave way to the deep lying piers up by Chelsea, built to accommodate the immense Trans Atlantic ocean liners.

Next door to the Citibank is a Subway sandwich shop, today looking rather forlorn underneath scaffolding. But if you look closely, you will discover a fine, stone staircase leading into numbers 9-11, Broadway.

via Raisch Studios

It was here, on the morning of April 15th, crowds began to gather on this staircase, for at least one New York newspaper had reported that the unthinkable had happened; that the unsinkable Titanic had sunk. Relatives and friends of passengers soon flocked here, desperate to find out news of their loved ones. Nos. 9-11 Broadway was the main office of several shipping companies, such as the American and Dominion Lines, as well as the White Star. As the growing crowd soon spilt over into neighbouring Bowling Green, it was left to a young office boy, Ismay, to try to pass on what little information he knew, all the while worrying whether his father, J. Bruce Ismay, the companies managing director had survived.

It was not until a few days later when the Carpathia docked uptown at Pier 54, that many finally discovered whether their loved ones were safe or had drowned. Maritime historian, John Maxtone-Graham wrote of how Ismay’s boss, C.W. Thomas, the assistant manager at 9-11, Broadway, “stood uptown on Pier 54, at the foot of the Cunard liner Carpathia’s gangway, weeping openly as survivors, clad in shipwreck motley, streamed ashore.”

Today, there is little to indicate what happened once happened here, but discerning eyes will notice that the old iron fence around the Subway sandwich shop is adorned with rows of stars, built for the company which once worked here.

Steamship Row circa 1882 © DCMNY

Steamship Row was perfectly situated. Running alongside Bowling Green, it was located adjacent to the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House. Today, the imposing Beaux Arts building is home to the National Museum of the American Indian, but traces of the steamship age can still be found within.

Most of America’s wealth passed through New York City, and at its centre, was the old Custom House; “a bustling place of activity, as brokers and custom agents worked together building the wealth of this nation.”

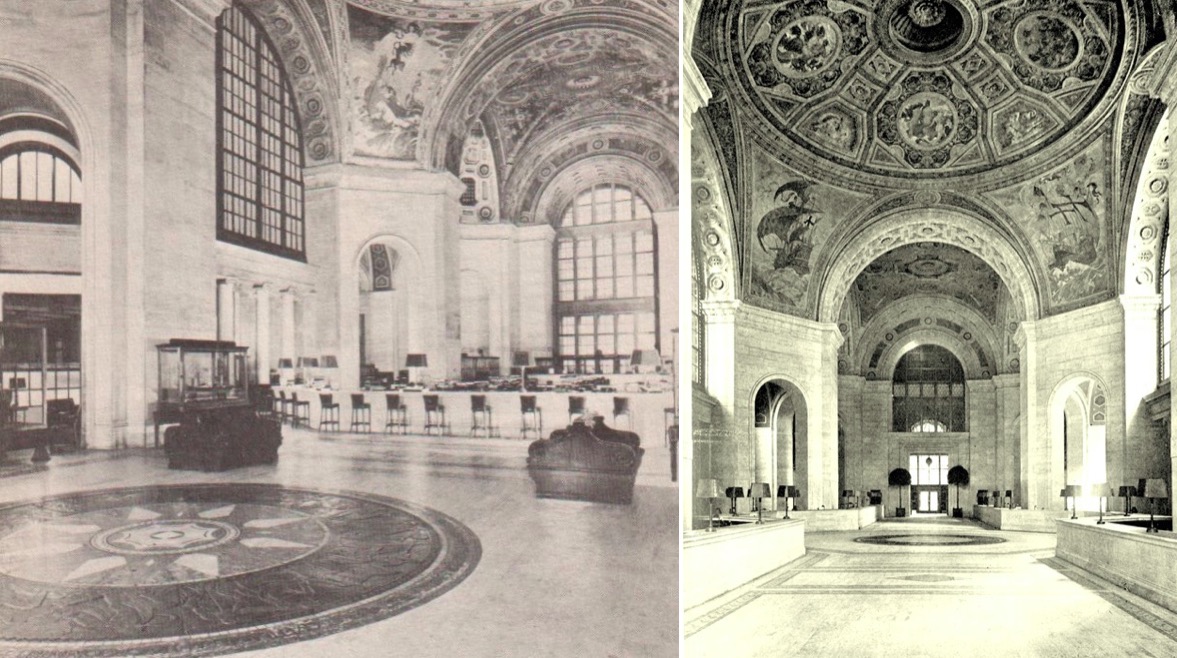

If you enter the now empty main trading floor of the Custom House and look up, you will see a series of vast, incredible murals, depicting the golden age of shipping in Manhattan. Painted by Reginald Marsh, as part of the WPA program, created during the Great Depression, the murals give an idea of what the bustling, daily life of New York harbour must have been like.

“It might not be today”, commented Wm Bixby, “but anyone studying the growth of the city, cannot be struck by the fact that New York was first a port before anything else.” The murals show tugboats carefully shepherding enormous steam liners into New York, waterfronts packed with longshoremen and stevedores loading Ford Model A’s, as never ending lines of immigrants, disembark under the ever growing Manhattan skyline.

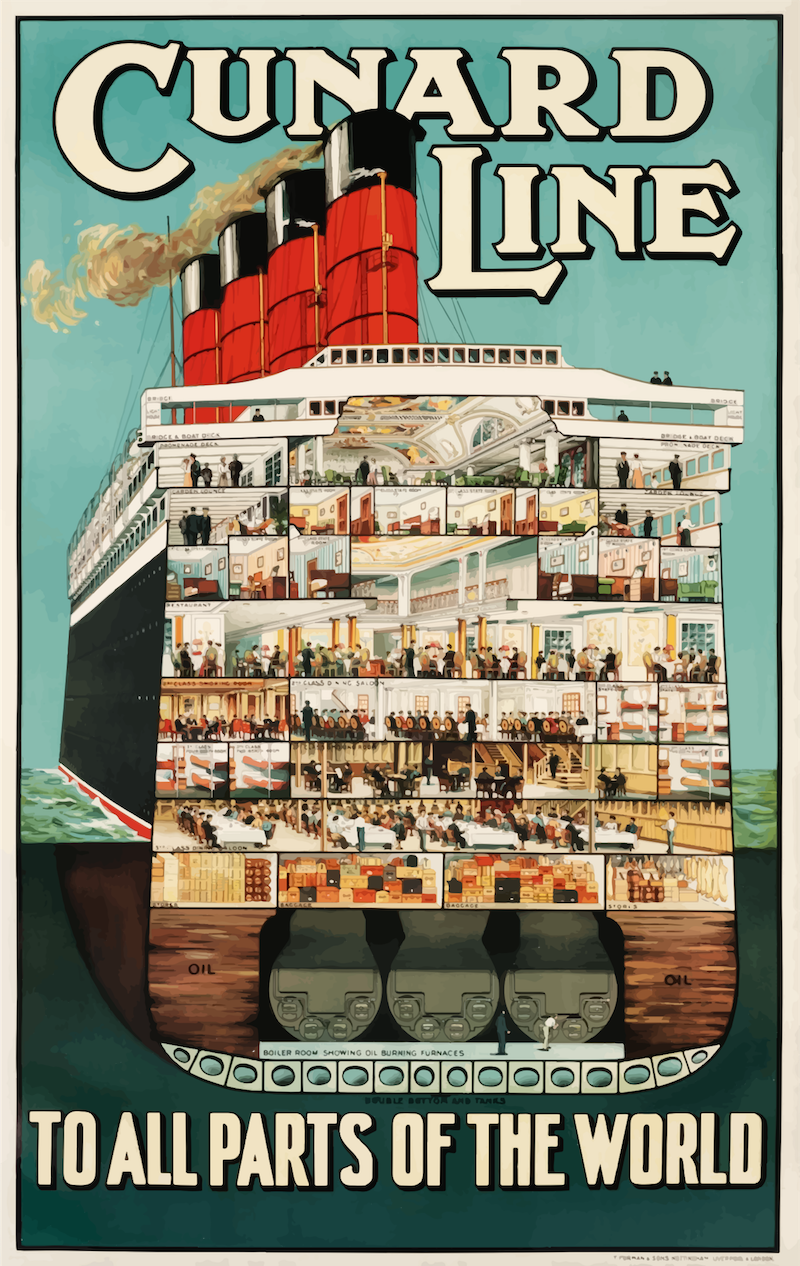

Our next port of call is back to Steamship Row, and the imposing Number 25, Broadway. Today the ground floor is occupied with an upscale venue space owned by Cipriani, and a not quite as glamorous gym, Planet Fitness. But carved in stone above the entrance, and emblazoned on its gleaming bronze doors, show that this once was home to one of the giants of ocean travel, the Cunard Line.

Cunard built and ran some of the grandest and fastest steamships to ever grace the ocean, ships such as the Mauretania, the doomed Lusitania, and the Queen’s Mary and Elizabeth, vessels so opulent, they were known as the Monarchs of the Sea.

Cunard’s New York HQ was appropriately just as grand. It had an enormous great hall, built along the lines of the Italian Renaissance, and adorned with elaborate ceiling murals showing the golden age of sail. This was once the ticketing hall for Cunard, and vast painted globes depicted their sailing routes.

© Larry Lederman via NYSID

The last ticket was sold here in 1968, and Cunard sold the building three years later. But the company still exists, and are the only remaining company still offering a regularly scheduled passenger service between Europe and New York. Today, it is still possible to come to America the old fashioned way, traveling from Southampton to New York, a voyage that Cunard has been running ever since 1848. The Queen Mary 2 takes seven nights to cross the Atlantic, evenings that can be spent dancing in the largest ballroom at sea.

But for every luxury liner, there were dozens of more pedestrian steam ship companies operating out of Lower Manhattan. Leaving the former Cunard HQ, heading across Bowling Green and walking down Beaver Street, we find at number 44, the offices of the New York Department of Sanitation.

But closer inspection shows an inscription above the first floor, saying ‘Kerr Steamship Co. Inc.’ The Kerr Company ran a passenger and freight service of steamers from New York to such far flung destinations as the old Dutch East Indies, Ceylon, and Egypt.

As we travel further along Beaver Street, to where it intersects with Pearl before turning into Wall Street, there is a closed branch of a Tumi luggage shop. Above the remnants of the Tumi sign is an engraved sign showing that this building was once home to a company called the Munson Steamship Line. It might not be known today, but at one point, the Munson Line was the largest ocean freight company operating out of New York. With a fleet of streamers, largely seized from Germany after World War I, the Munson dominated the route from New York to Cuba. Boasting of the ‘fastest time and fastest ships’, the Munson Line added a passenger service in 1919, offering exotic cruises to New York – Nassau – Miami – Havana.

The Munson Line extended their routes in the 1920s, offering first class fares to Rio de Janeiro in ‘new palatial ships – unexcelled service!’, for just $295. But the Great Depression saw the Munson Line go out of business in 1937.

SS. Normandie in New York © Museum of the City of New York

The golden age of ocean travel by steamship maybe long gone; cheaper airfares soon saw the end of week long voyages, and steamer trunks. But these hidden, and mostly overlooked fragments, tell of a time when the most delightful way to travel the world, was by sea.