Forgotten feminist icons of the French military, the Vivandières, alternatively known as cantinières, was the French title for women attached to military units who sold wine to the troops and offered better cuisine on the battlefield than the army could offer. An often overlooked part of women’s and military history, while they were not sanctioned to do any fighting, there are countless reports of many women who did. They began as supporters, originally tasked with providing home comforts to those in the field or at camp and quickly rose to become a fundamental part of the army.

The Vivandières tradition is believed to have began in French Army regiments during the early 18th century. Most Vivandières were married or related to soldiers in their regiment, despite popular belief that they were prostitutes or nothing more than “camp followers.”

History has long records of soldiers’ wives traveling with armies and before the 18th century, armies were often reported to have more women and children than soldiers in their camps.

The French army was the first to give the accompanying women a clear category and role during the French Revolution, up until which point, the right to sell wine, food, tobacco, writing paper, wig powder or any type of amenities to the troops belonged to a special group of eight privilidged male soldiers, effectively creating a monopoly for them.

It was a good business too, as the troops were rarely provided with food, drink or other items beyond basic rations. The vivandières kept soldiers from straying from camp in search of these extras, lowering the possibility of desertion.

Often too busy however with their military duties, the male vivandiers were granted permission to marry and pass on their private enterprise to their wives, who became ‘vivandières’…

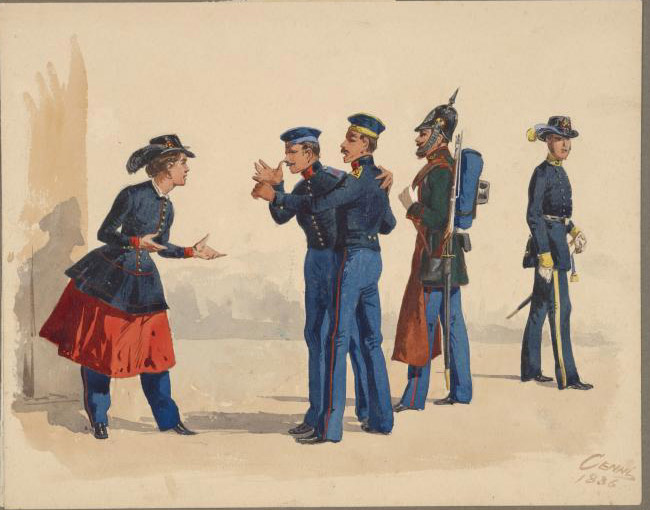

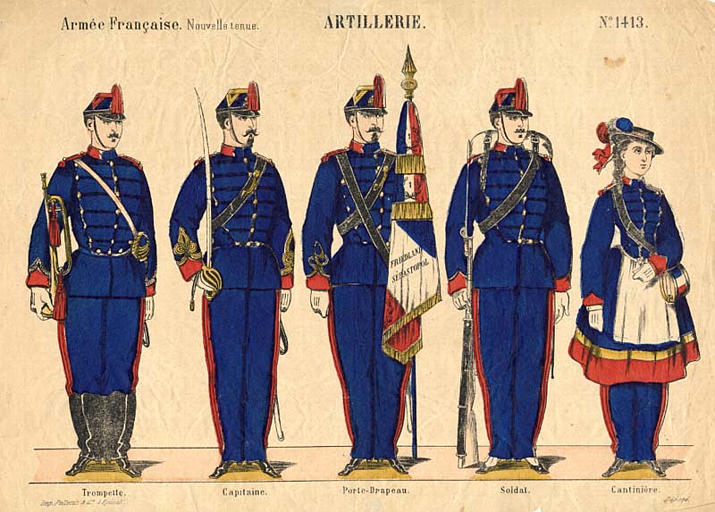

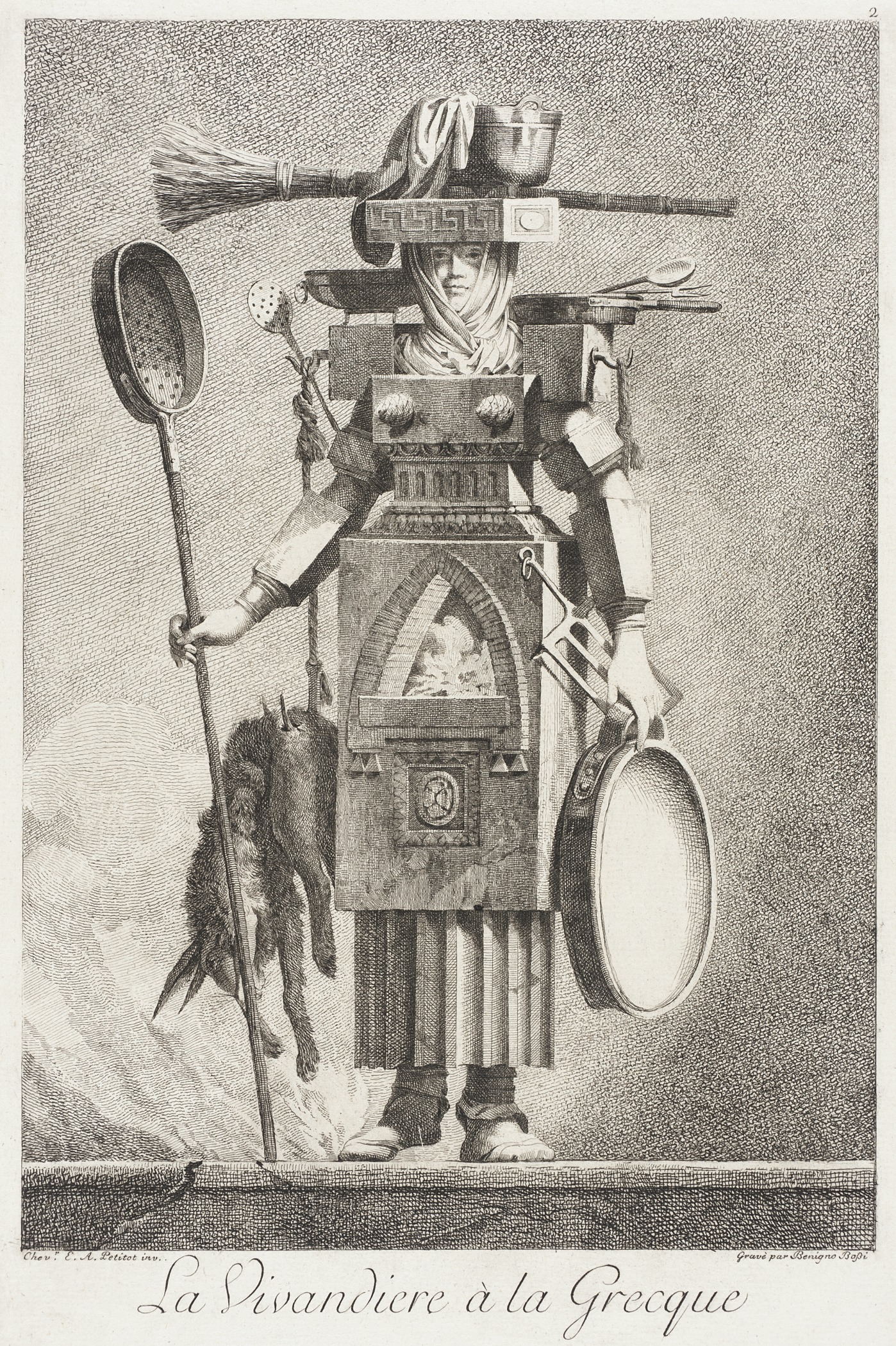

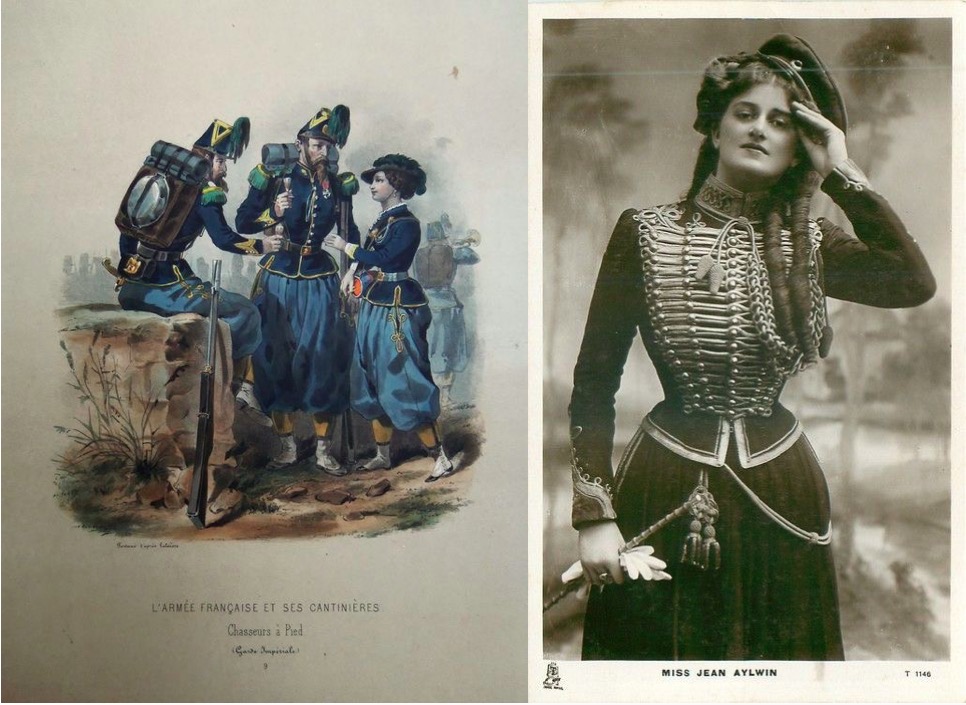

Not much research or historical documentation exists on the vivandières, but various artistic depictions and the work of amateur historians allows us a glimpse of these fascinating female soldiers. While their role has been understated, their military dress, however, would suggest otherwise.

The bold, feminized versions of military uniform highlighted their importance among the ranks, and the similar level of distinction afforded to them in the line of duty. They were said to have led the regiment on parade and while marching, suggesting they were valued, esteemed members of their military units.

A discarded soldier’s jacket may have been re-appropriated by a cantinière and improved upon, allowing more freedom of movement to ride horses and navigate quagmired battlefields.

Certainly, the use of trousers was ahead of its time, displaying the practical nature of their role. Juxtaposed to the male members of their regiment, their dress was often quite similar aside from a few accessories and feminine touches. Said to have evolved from features of the Zouave uniform, the women’s dress consisted of bright colours, hats and canteen accessories.

Typically, a Vivandières uniform consisted of a short skirt or dress over trousers and their trademark tonnelet (a small barrel suspended from a shoulder strap used to dispense alcohol). This iconic accessory became the totemic symbol of the vivandières and cantinières; in the future this imagery would be adopted by companies and used in patriotic advertisements.

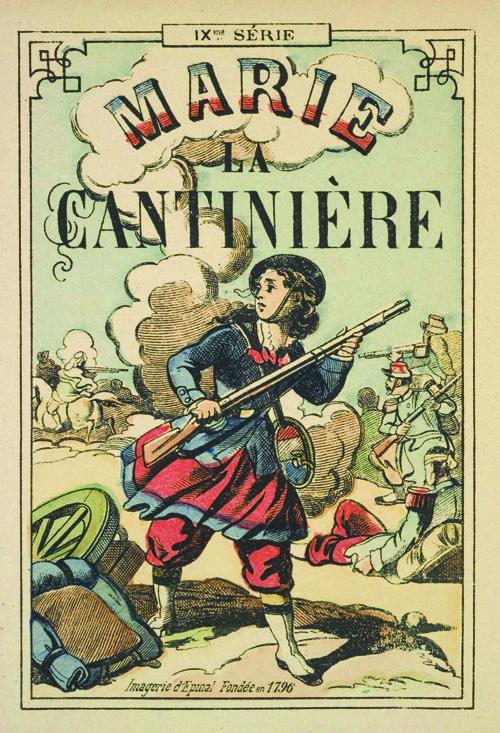

The Vivandières’ role evolved from canteen keepers to include everything from an auxiliary presence at camp, to acting as nurses and support to the troops, to taking part in battle themselves.

Vivandières were key to maintaining a successful army by managing supplies and providing logistical support to those at war, therefore ensuring the livelihood of French soldiers. They served as prominent members of the French Army from the early 1700s up to World War I.

While Vivandières may have gotten their start in France, the practice was widely imitated and equivalent versions of their role have appeared in armies across the world.

They served on both sides of the American Civil War and in the armies of Spain, Belgium, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and various armies in South America. Though their tales are absent from most records or official narratives, they played an integral part in wars we are most familiar with.

In the American Civil War, vivandières on both the Union and Confederate sides were known as “daughters of the regiment.” On the battlefield they were brave soldiers, charging to the front lines shoulder to shoulder with their male comrades in arms.

Despite an ongoing lack of distinction among military historians, images and documents of vivandières remain powerful reminders of these courageous women. Their legacy has been most prevalent in advertising, patriotic imagery, and stories in opera and theatre. And who wouldn’t love a soldier who’s always got the wine and snacks sorted?