Are you haunted by the ghosts of your social mistakes? Have you ever suffered the humiliation of fluffing a greeting with an acquaintance in the street? Or the ignominy of using the wrong fork at the dining table? Around a century ago, such social gaffes and embarrassing blunders were seen to be daily pitfalls, waiting to heap shame upon novices stepping out into society. Fortunately there were a wide range of etiquette books to help you navigate these lurking social faux pas, that were waiting to land you not just in the soup, but near the tureen as well.

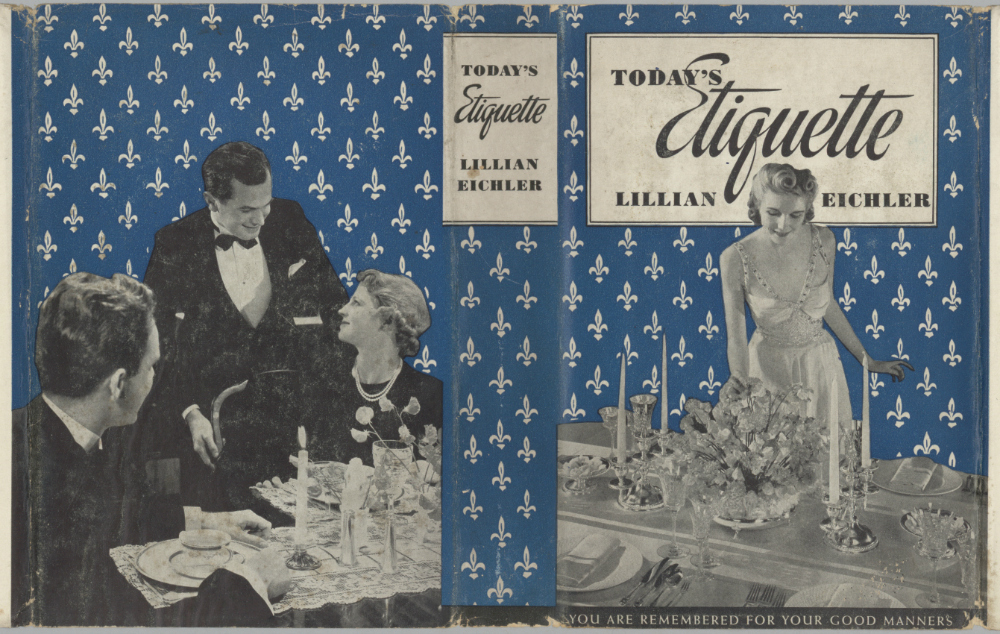

Authors such as Emily Post became household names. Her seminal 1922 book on Etiquette created an impeccable empire of good manners, a legacy of breeding that still exists today as a family run Etiquette Institute. But there was one particular book on etiquette that contains an incredible story: ‘The Book on Etiquette’ published by Doubleday in 1921 proved to be widely popular, selling over two million copies. What was remarkable about this two volume self-help book is that was it written by a young woman, just twenty years old. Lillian Eichler may just be the most incredible woman you’ve never heard of; an advertising prodigy, best selling author and self-made millionairess, who is virtually anonymous today.

Here at Messy Nessy Chic, we’ve tracked down some of her surviving family members, including Eichler’s 100 year old sister in-law, who helped transcribe and edit some of her books, to tell the untold story of one of the great unknown writers of the Jazz Age.

Lillian Eichler was just 18 years old, when in 1919 she was taken on by the New York advertising agency of Ruthrauff and Ryan as a copywriter.

Ruthrauff and Ryan was a ground breaking ad company, known for abandoning large, lavish illustrations in their ads, and adopting a tabloid style, newspaper story, complete with eye catching headlines and action photos.

The agency assembled an all-star team of copywriters, including Maxwell Sackheim, creator of the ‘Book of the Month Club’, Victor Schwab, hailed as the greatest mail-order of copy-man of all time. And in the midst of this hard-boiled team of Manhattan ad men was, incredibly, a teenage girl.

Lillian Eichler was born to Jewish Hungarian immigrants, who ran a cigar shop in Harlem. She proved to be a naturally talented wordsmith. With no college education, but studying at night, Lillian Eichler looked to find a position with an ad agency in Manhattan. “She was a most brilliant woman”, explains Harriet Eichler, her sister-in-law. “She went to the leading agency in the city, only to be told ‘that they don’t hire Jewish people, or women.” Harriet, nearing her hundredth birthday tells of how Lillian wasn’t put off, but asked them to at least look at what she’d written. She was hired on the spot as a copywriter.

For that to happen to a female teenager today would be remarkable, but nearly a century ago, it is even more so.

Lillian with her younger siblings

Eichler proved a natural at ad work. Her grandson, Alan Eichler explains how she was “very bright and advanced quickly. One of her most famous campaigns was for Rinso white laundry soap, for which she wrote the popular Rinso White jingle, ‘Rinso White, Rinso White, happy little washday song.’ ”

But it was Ruthrauff and Ryan’s account with Doubleday Publishers that would lead to Eichler creating what is still considered today in advertising circles, one of the 100 greatest ads of all time.

Etiquette help books have been around ever since gentlemen have been forgetting to tip their hat to a lady. John H. Young’s, ‘A Guide to the Manners, Etiquette, and Deportment of the Most Refined Society’ was a huge success in 1879. “No one quality of mind and heart”, Young stated, “is more important as an element conducive to worldly success that civility.”

Maud Cook’s 1899, ‘Hand Book of Etiquette’ provided such helpful tips for the ‘Lady of Gentleman at Home and Abroad’, such as advising against ‘heavy velvets or gorgeous trimmings…or jewels’ to be worn by any girl under twenty one. “Sweet simplicity alone….are what we want most to see.”

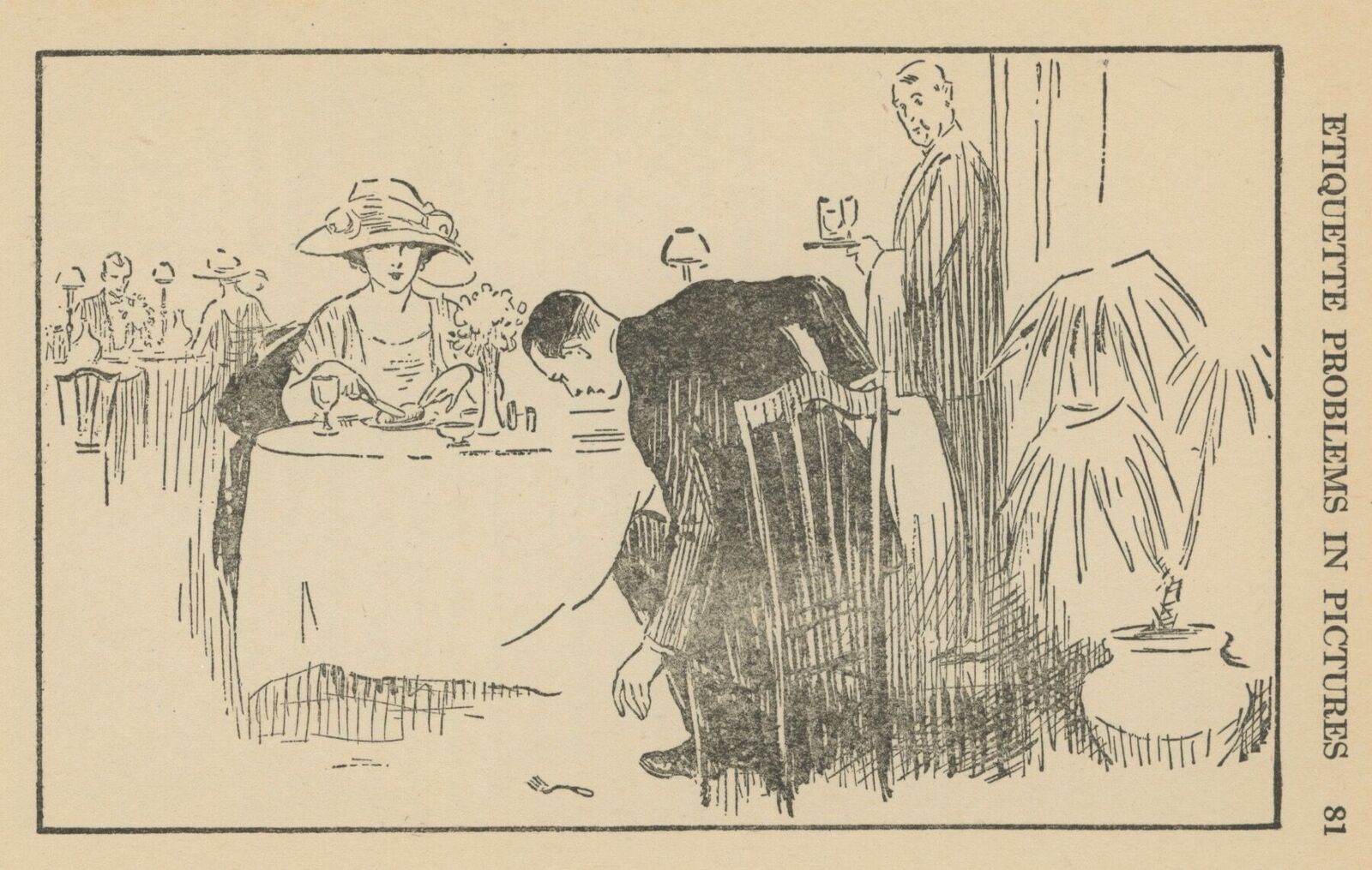

Formal dinners alone were a minefield; there were forks for oysters, separate forks for the fish course; yet more silverware for the ensuing roasted meats, silver tongs for asparagus, never ending spoons for sauces, vegetables and gravies; pickle forks, scissors for cutting grapes from the stem, and ornate scoops for ices and sherbets.

Heaven forbid the poor individual who used the wrong cutlery at the incorrect time!

Etiquette books were big business, and Doubleday, one of the largest publishers in Manhattan, meant to have their own. They published a book in 1922 called ‘The Encyclopedia of Etiquette’ by Eleanor Holt. But the guide for ‘What To Write – What To Wear – What To Do – What To Say’ was proving a tough sell. Written in a stiff, Victorian style, it was proving too antiquated for the Jazz Age: “Chaperonage at the Theatre and Opera – In strict society it is contrary to the social law for an unmarried woman to attend the theatre in company with a man without a chaperon.”

With 1,000 dusty copies left unsold, Doubleday turned to its ad agency to help shift the books. Ruthrauff and Ryan gave the problem to its star, young copywriter.

Lillian produced a campaign showing an agitated guest spilling a cup of coffee over the table cloth, with the caption ‘Has This Ever Happened To You?’ The ad swiftly sold the 1,000 copies of Holt’s encyclopedia, but they were just as quickly returned, readers finding the tone too old fashioned.

Doubleday hit upon the idea of having this fusty book filled with Victorian social dilemmas, being re-written and modernized. And who better to put a Jazz Age spin, than the copywriting prodigy that had created the ad.

“My mother was asked to rewrite this out of date book to make it more appropriate for the time”, recalls Anita Weinstein, Lillian’s daughter. “She was a very ambitious young woman. She was very proud that she was one of the very few women who would drive over the bridge [from Queens] to work in the city.” Astonishingly for 1922, the young copywriter not only re-wrote the book on etiquette, but dreamt up the ad campaign to sell it as well.

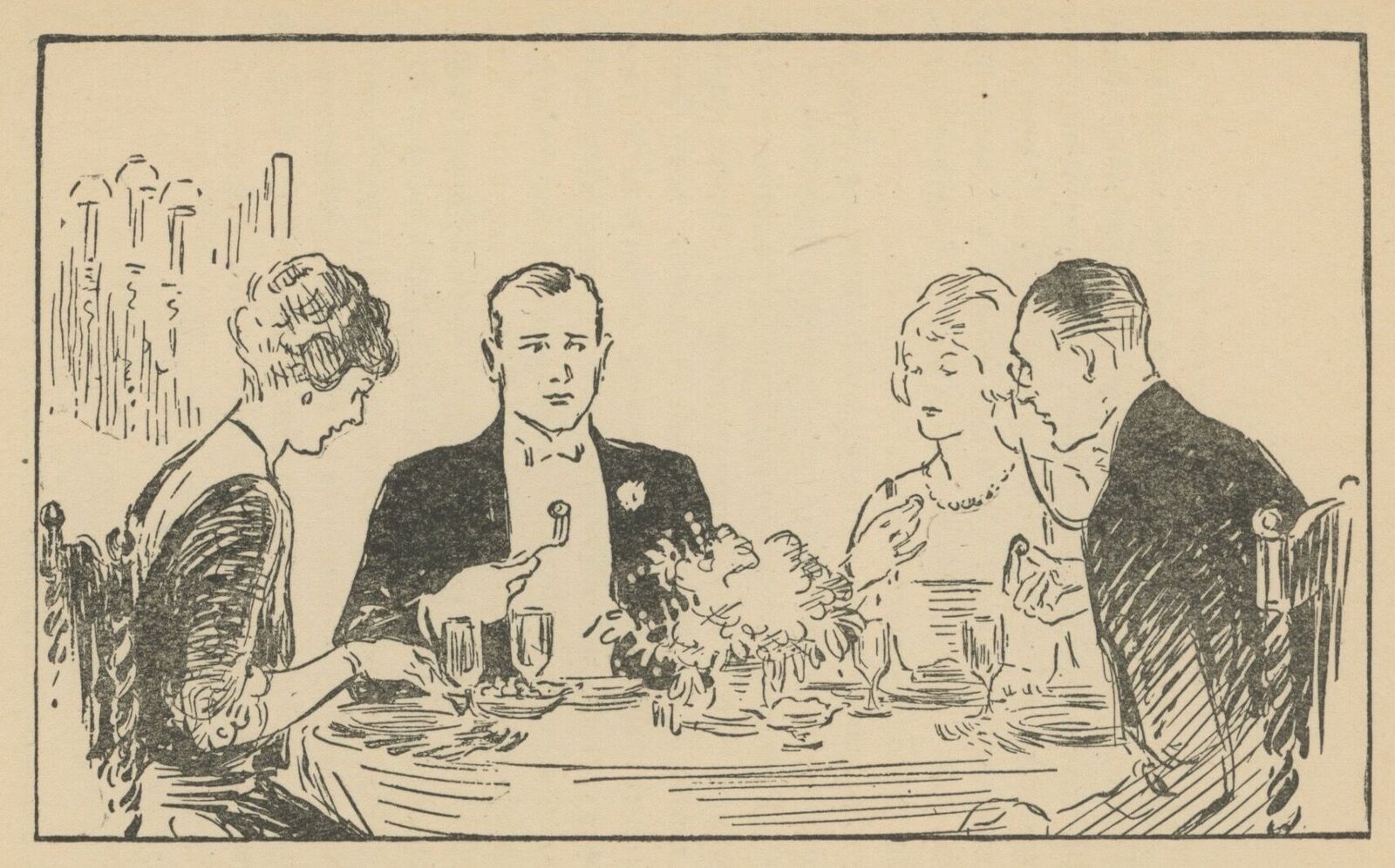

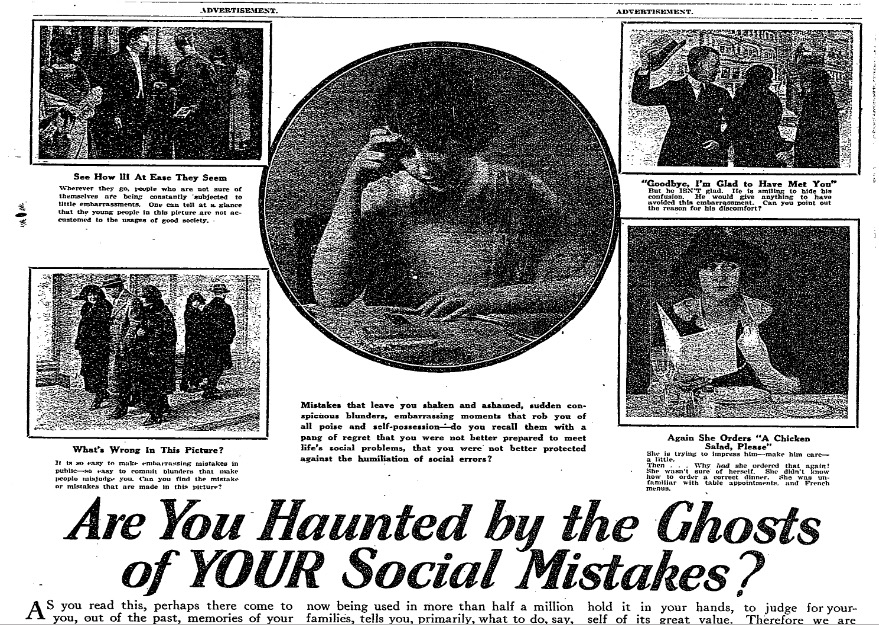

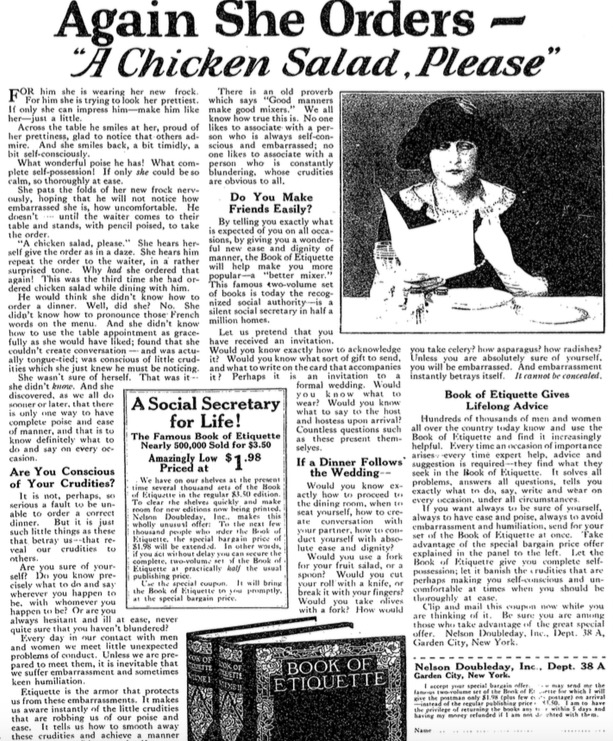

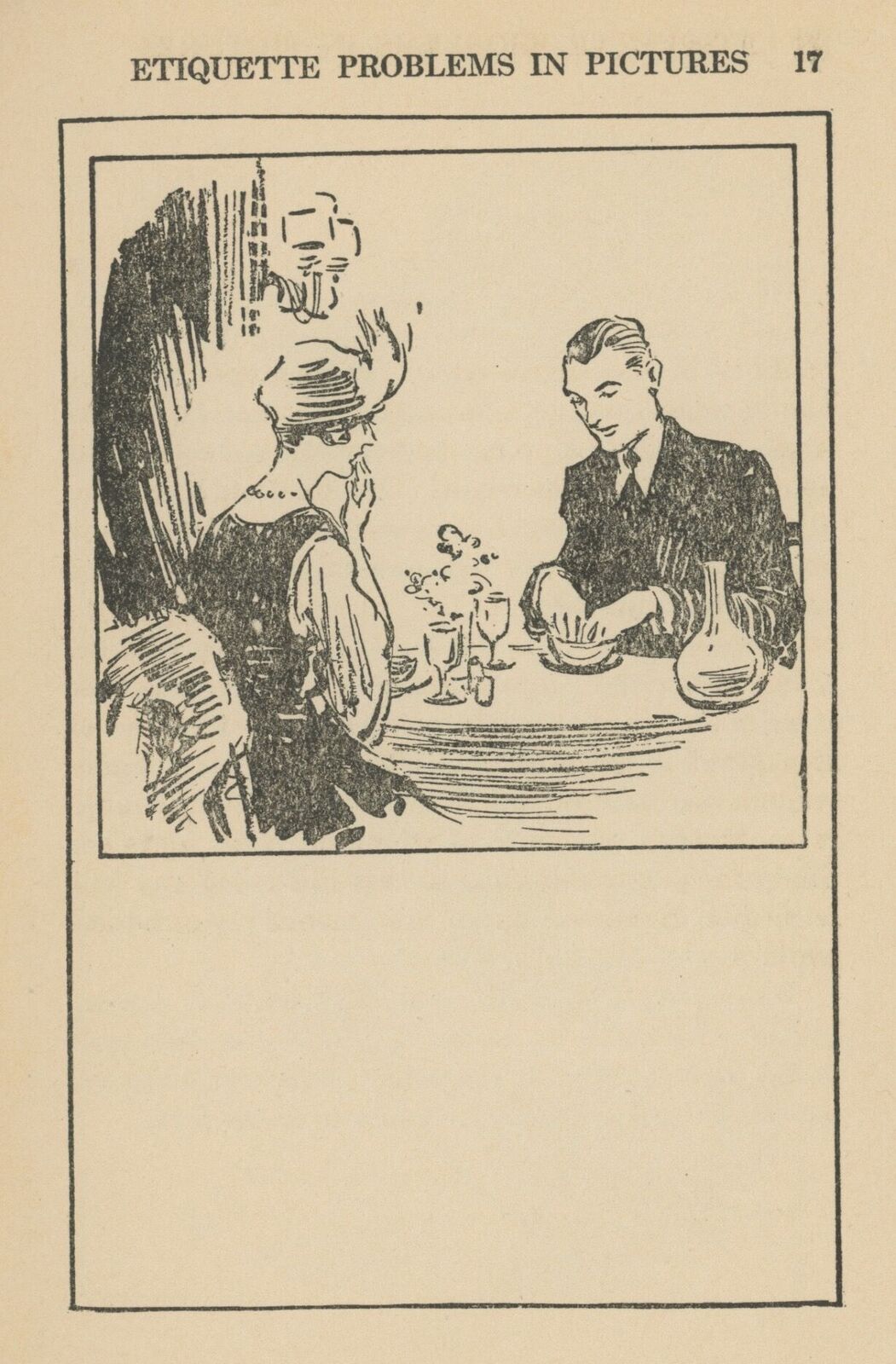

One ad ran with the first sentence you read in this article, ‘Are You Haunted by the Ghosts of YOUR Social Mistakes?’ The other ran with the tag line ‘Again she orders – a chicken salad please.’ In the tabloid ad style favoured by Ruthrauff and Ryan, the ad showed a flapper looking disconsolate at dinner. She’s wearing a modern cloche hat, and fine white gloves to match the sophistication of the restaurant, but our despondent heroine is let down by not knowing how to navigate the extensive menu with its French bill of fare.

“For him she is wearing her new frock….for him she is trying to look her prettiest…Across the table he smiles at her, proud of her prettiness, glad to notice that others admire,” runs Eichler’s advertisement.

“What wonderful poise he has! What complete self-possession! If only she could be so calm, so at ease”.

The campaign tells the story of a girl repeatedly ordering chicken salad……who can never decided whether to invite her dismayed escort in or not at night…..who practically wrecks her marriage in advance by seizing the arm of an usher instead of her father as they start the wedding march.

The answer to these social pitfalls could easily be found in Eichler’s own book, which she billed as ‘the armour that protects you’. (“Regular price $3.50 knocked down to $1.98”)

The campaign was a runaway success, and Doubleday swiftly sold two million copies of her book. It came in two volumes, with gilt edges, with illustrations showing the young, smart set of the early 1920s. All of which incredibly stemmed from the imagination of a thoroughly modern, young woman flourishing in cut and thrust of hard nosed Manhattan ad men.

“There are times when even the most well-bred among us falter and are embarrassed”, wrote Eichler. “Some un-expected situation, some unusual circumstance, and we are thrown into a flurry of awkward excitement. How much better to impress by our faultless manners, our ease and calmness.”

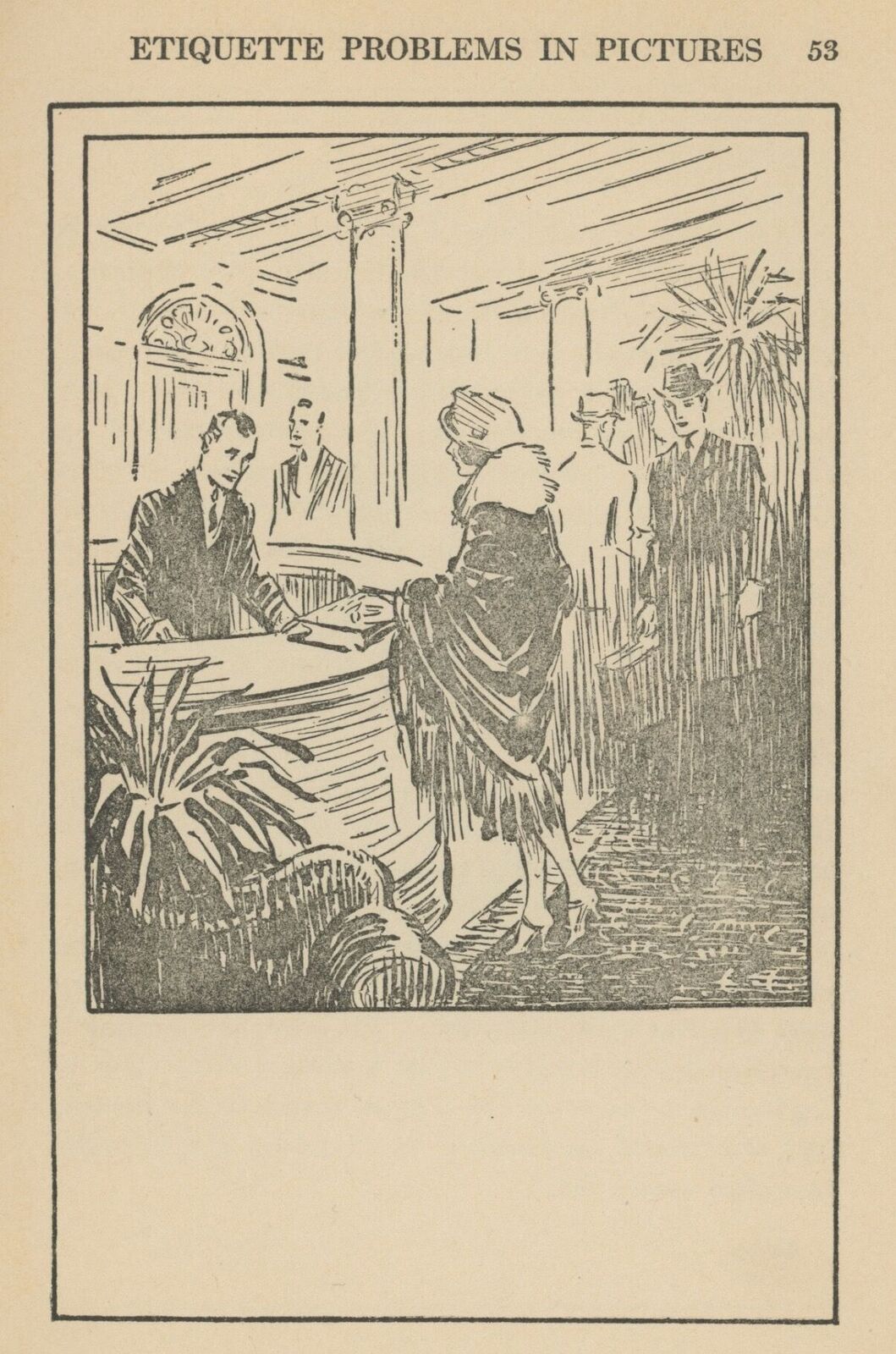

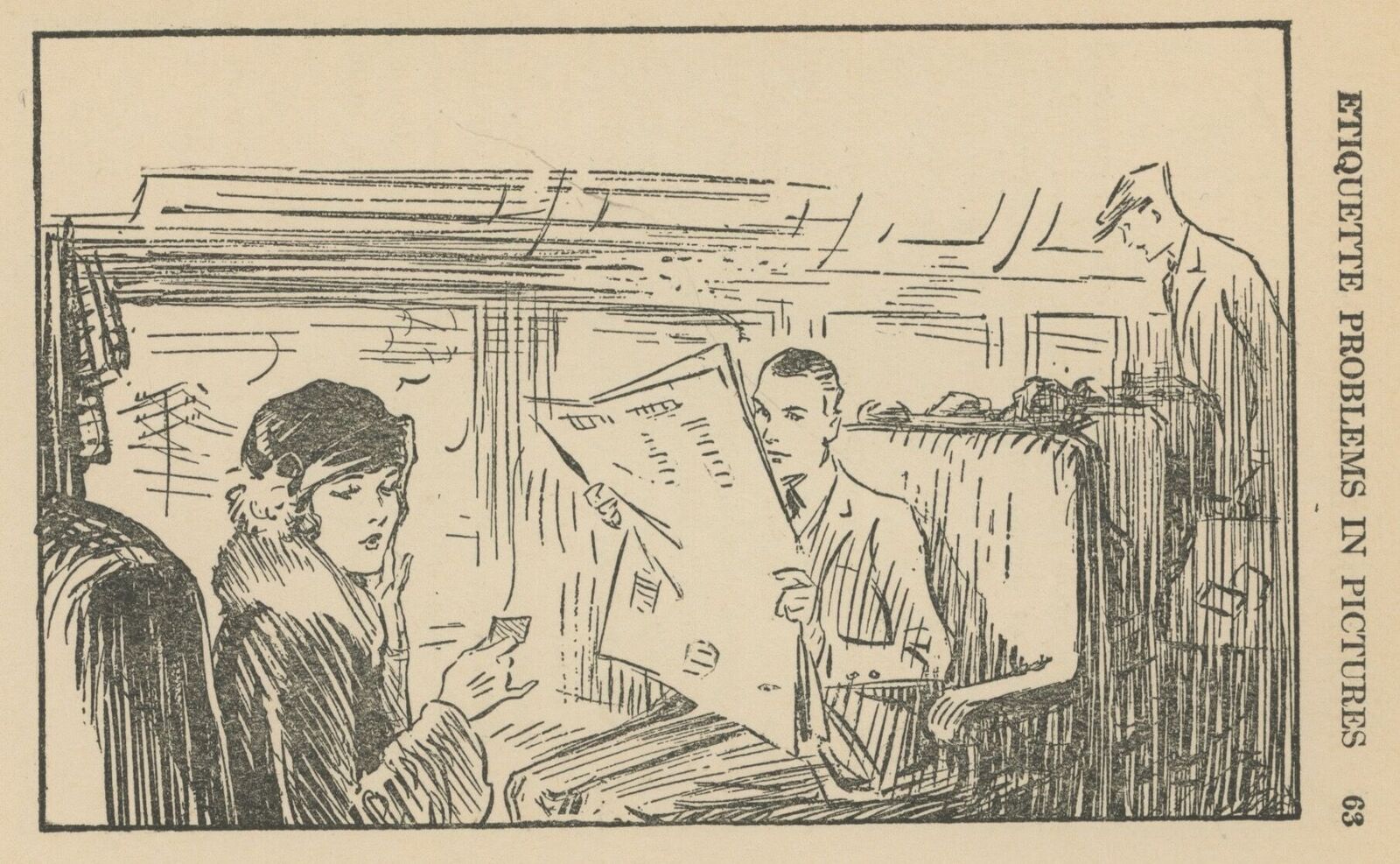

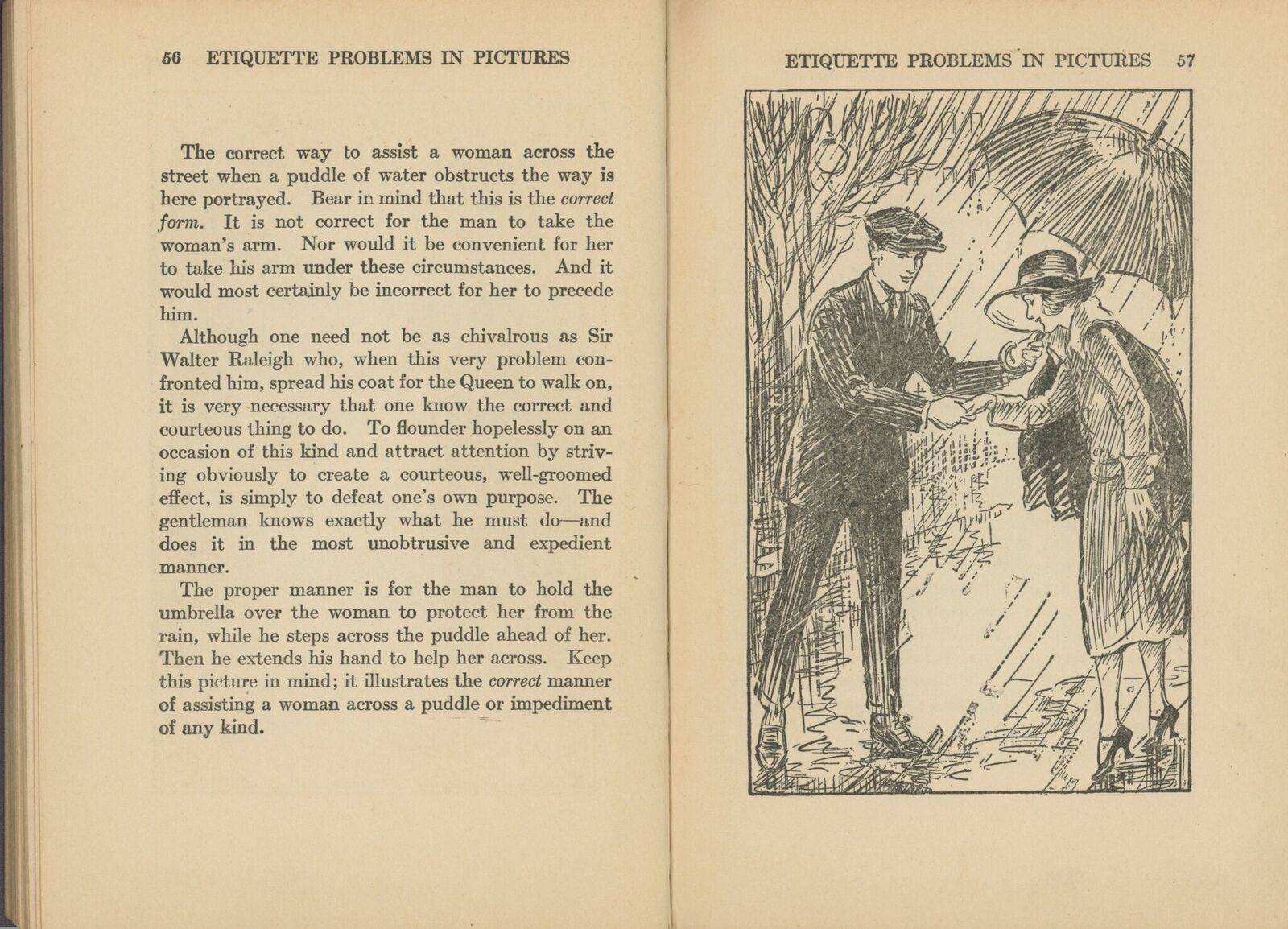

A large part of the book’s success was down to its modernity; Eichler wrote of the problems facing the increasingly independent woman of the Jazz Age. She laid out the correct way for a solo woman to check into a hotel alone, or how to behave when seated across from a strange gentleman in a train carriage, (she should face forwards, whilst he should occupy the seat opposite), with advice on how to deport herself in the dining car (“never hatless”).

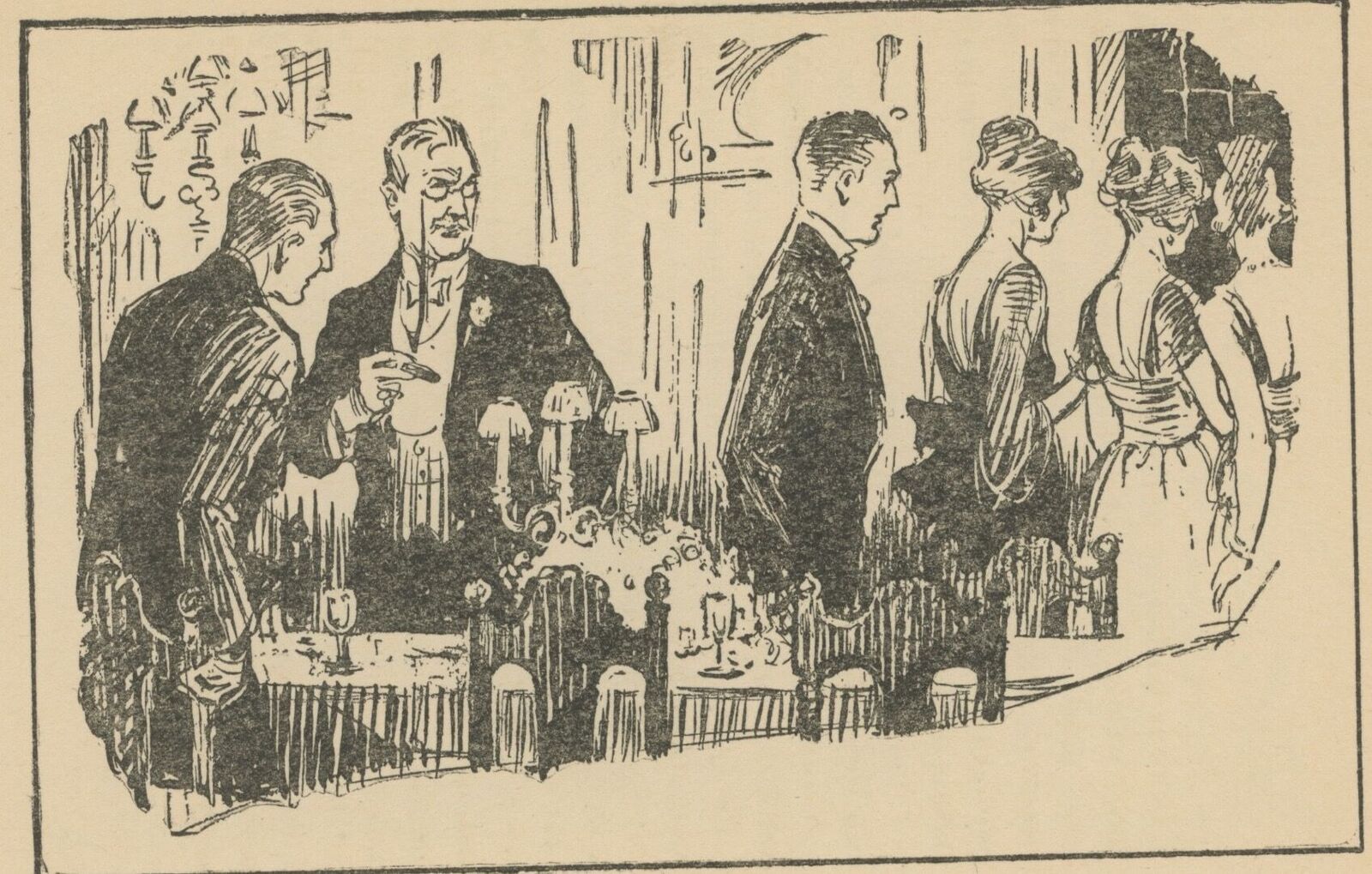

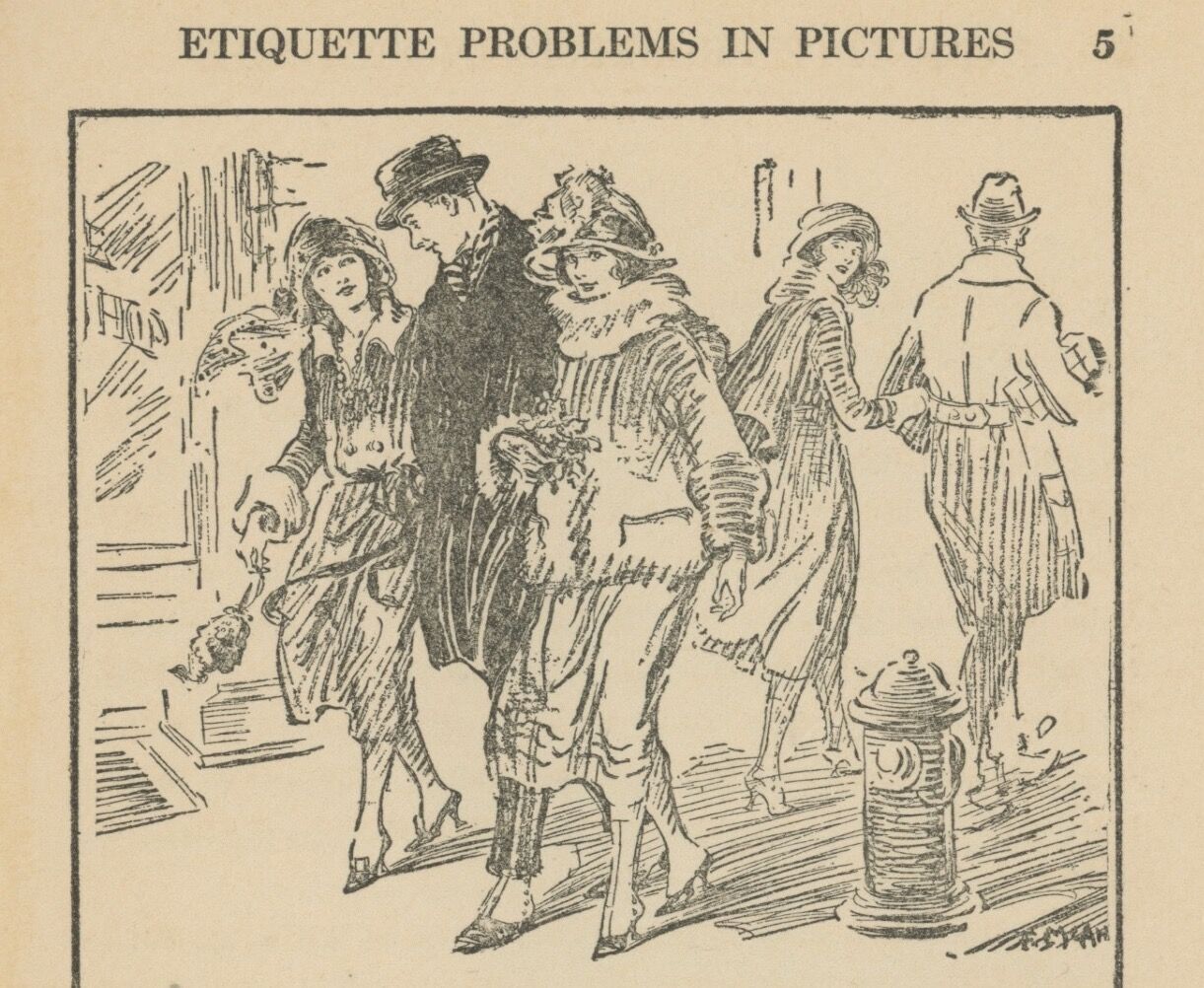

It is easy today to laugh at this bygone world where “the manner of a gentleman walking with two women in public is quite as important as the manner of addressing them in the drawing-room”, and where “table manners are as sure an index to breeding as the table of contents is an index to what the book contains.” One illustration shows a well dressed group of two couples at dinner in full evening dress, with three staring at the gentleman in the middle who has committed the horrifying social blunder of “helping himself to olives before anyone else……he has also used a fork instead of his fingers.” The end result? : “the enjoyment of the evening is undoubtedly spoiled!

But Lillian Eichler’s rewriting of the Book of Etiquette shows a world where women were increasingly independent, and where men were always gentlemen ; a sadly vanished world, where, “it hardly seems necessary to mention in a book of etiquette, that the hat should always be removed when greeting a woman acquaintance.”

Whilst Emily Post was formal and detached, Eichler was far more vibrant, friendly and accessible. Allegedly, Post, who came from a genuine social standing, was so furious that she exclaimed that “this teenage daughter of Jewish immigrants would dare write a book about etiquette!”

Incidentally, when walking with two women, the gentleman “doesn’t walk in between but next to the curb”, and “lifting the hat should not be done in the spirit of an unwelcome duty. There should be a smile behind it, a warmth of greeting, a spirit of sincere courtesy.”

Eichler on honeymoon with her husband

Eichler was able to write in an entertaining popular way that, according to Carrie Tirado Bramen in her book, ‘American Niceness : A Cultural History’, appealed to a “mass audience of first and second generation Americans in ways that her competitor Emily Post could not. Eichler was a Jewish teenager from New York City who became a self-made millionaire and without a doubt the great forgotten figure of American manners.”

Part of the reason that Eichler is virtually unknown today when compared with Emily Post, is that she all but disappeared from the world of advertising in 1925. She married a Dr. Tobias Watson and with the proceeds of her best selling book, built an exquisite mansion in Jackson Heights, Queens, where she raised a family, and continued to write further books on etiquette, a standard book on letter writing, an anthology of literature called ‘Light From Man Lamps’, a pioneering anthropological works on social manners and behaviour amongst others.

For Alan Eichler, his aunt was a “very elegant, refined, self-educated lady, a true ‘Mrs.Etiquette’. She had grown up over a cigar store in Harlem, but transformed herself into the lifestyle she wrote about. She really shouldn’t be forgotten.”

We asked her daughter just how impeccable were her mother’s manners, and whether she would ever instruct on etiquette. “She just handed me a copy of her book”, remembers Weinstein, “saying ‘in there you’ll find the correct way to behave.’ ”