The Champagne region of France is one of its most famous; home to such grand wine houses, as Taittinger, Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin, Krug, Pommery and Ruinart, as well as dozens of smaller vineyards that make the sparkling wine known the world over. But underneath the lush, rolling landscape lies a secret world : miles of complex tunnels, hidden rooms and vast subterranean caves, some dating as far back as the Roman occupation. Dug into the solid chalk, they were used for maturing countless bottles of champagne in the cool, underground air. During World War One, these labyrinths of cellars filled with luxurious wines, were transformed into underground cities…

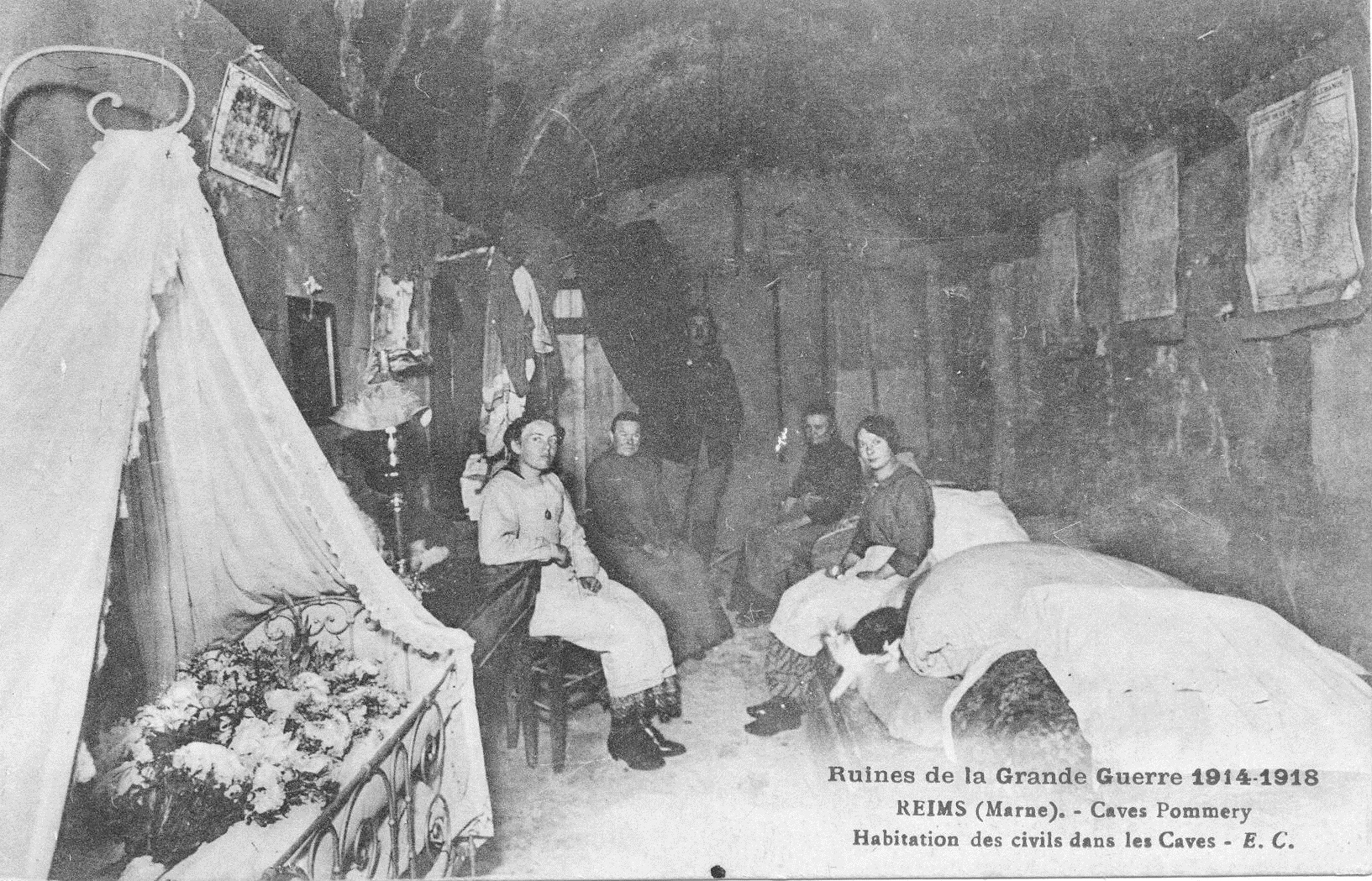

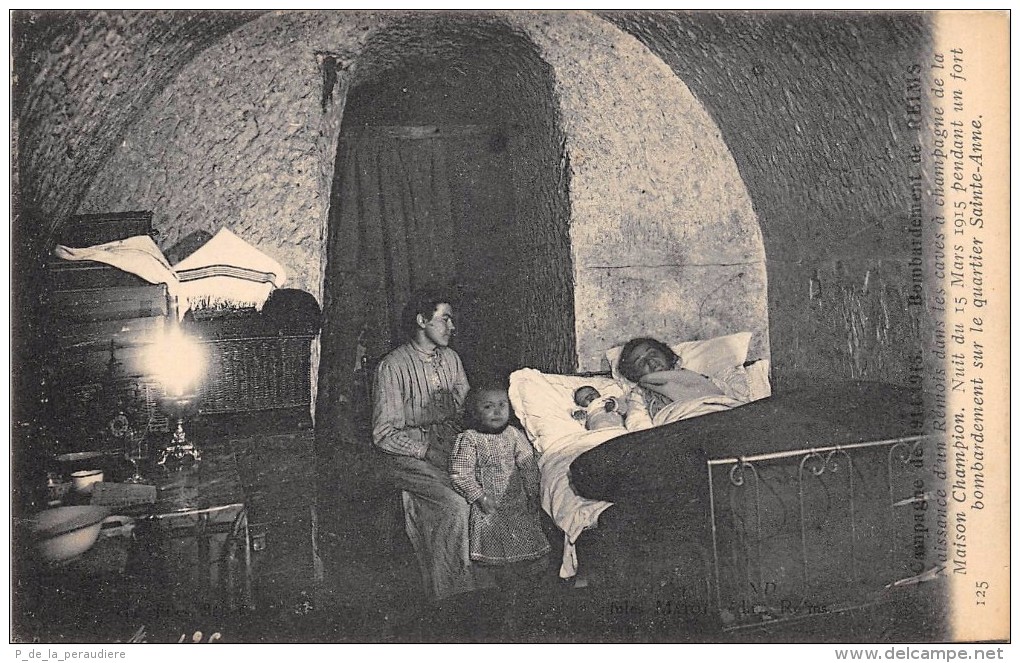

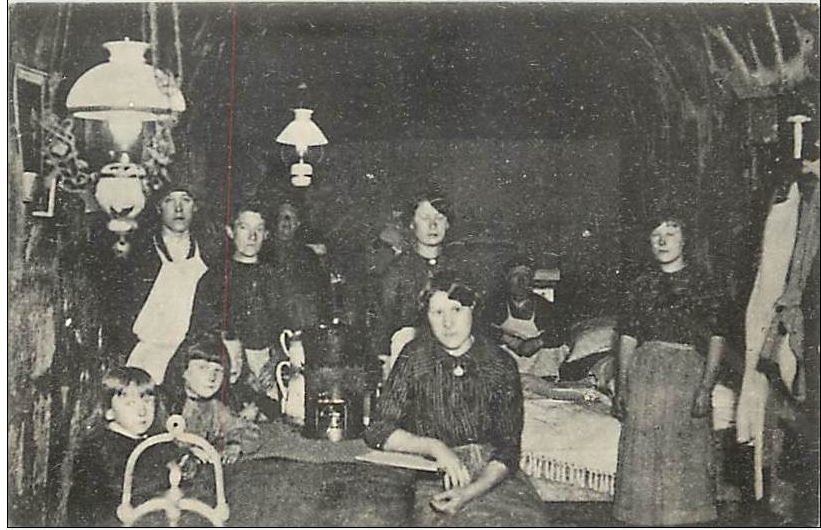

It is a story little known, but here the people of Champagne found shelter from the devastation of the Great War raging above ground. They made schools, hospitals, sleeping quarters and safe havens, living for years underneath the horrors above.

And here at Messy Nessy Chic, we love obscure, secret history almost as much as sipping fine champagne! So a trip to explore the hidden world under the vineyards and chateaus of les grandes maisons, which still exist and are used today, was certainly in order…

The Champagne region is centered around the historic and ancient cathedral city of Reims. Its climate and chalk terrain work together to produce the particular sparkling wine that made the area famous. “Amidst the flat plains of grain and corn in northeast France lies one of the great wine regions of the world, Champagne”, wrote wine columnist for the New York Times, Frank J. Prial. “Jutting suddenly out of the placid golden fields are cliffs of white chalk and vine covered rolling hills struggling to soak in the sun, often shrouded by the grey hues of a ‘Champagne sky’.

Located in the north east of France, the old city and surrounding tens of thousands of acres vineyards took on another importance in 1914 : for they stood right in the path of the German advance. As the German army poured through Belgium and France in the direction of Paris, Reims became a key strategic target.

But Reims was just as important to the heart and morale of every Frenchman and woman; for this is where twenty five Kings of France had been crowned, starting with Louis XII in 1223. Dominated by the immense, 800 year old cathedral of Notre-Dame de Reims, this is where a seventeen year old Joan of Arc brought Charles VII in victory. Losing such a hallowed city to the Germans was unthinkable.

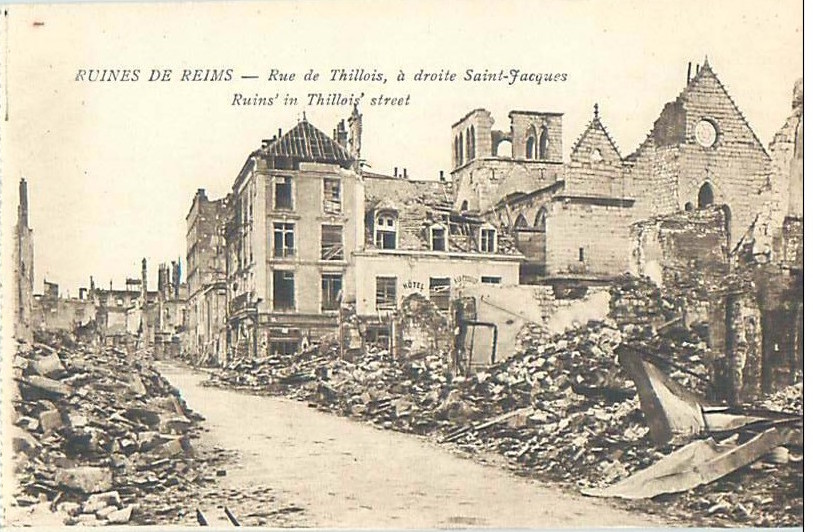

The German army descended on Reims on September 4th, 1914. Bitter, bloody fighting saw the French desperately defend their ancient city, and after a week, the Germans retreated. They took up new positions on the hilltops of the champagne vineyards overlooking the city; if Reims could not be taken, the German high commanded decided to destroy it.

German artillery began to pulverize the historic city, entrenched in a front line that would barely move for the next four years. On one day alone, nearly 3,000 shells would fall on the devastated city.

Faced with such horror and destruction, the civilians of Reims didn’t flee their home. Instead they sought refuge underneath it.

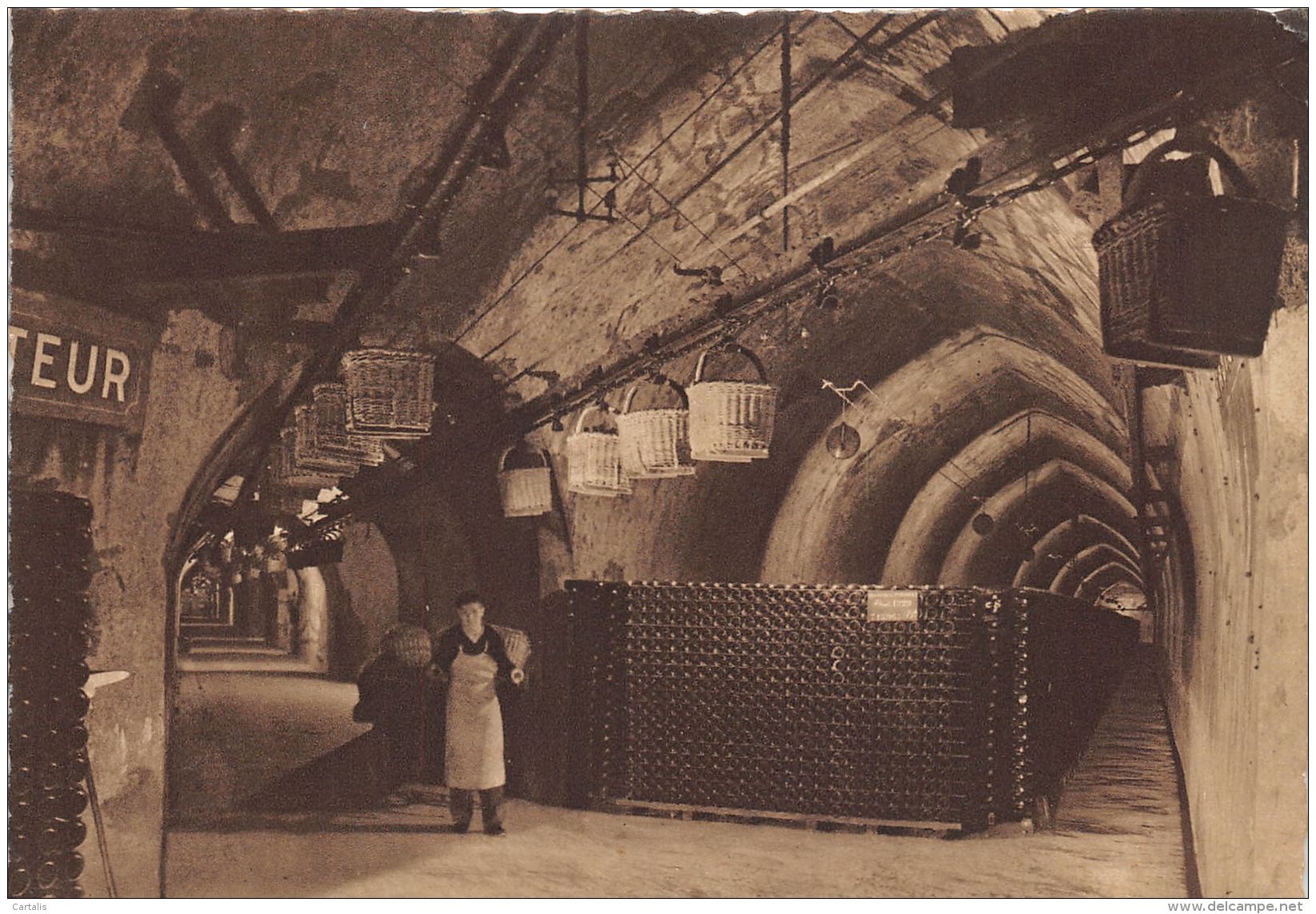

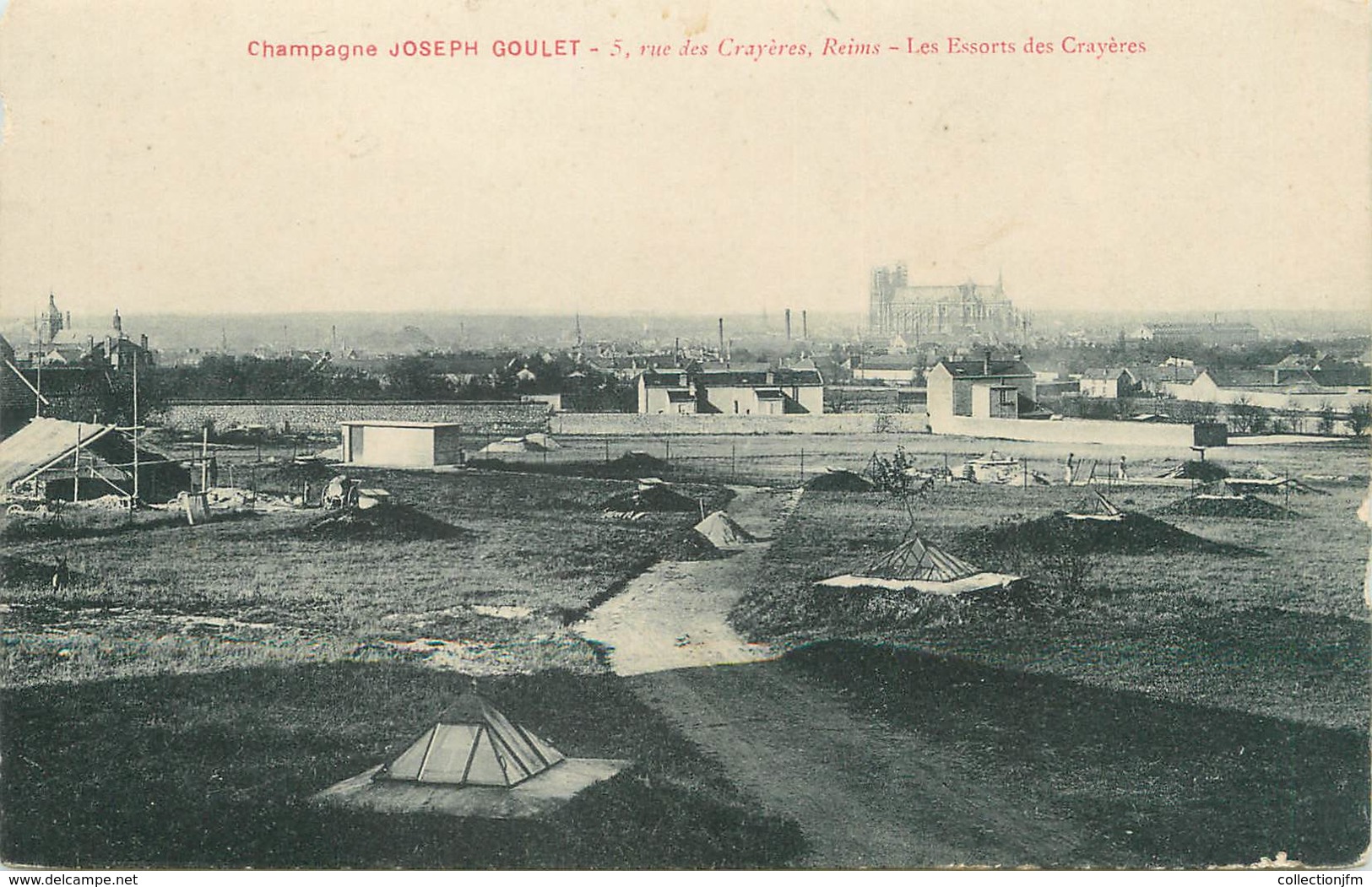

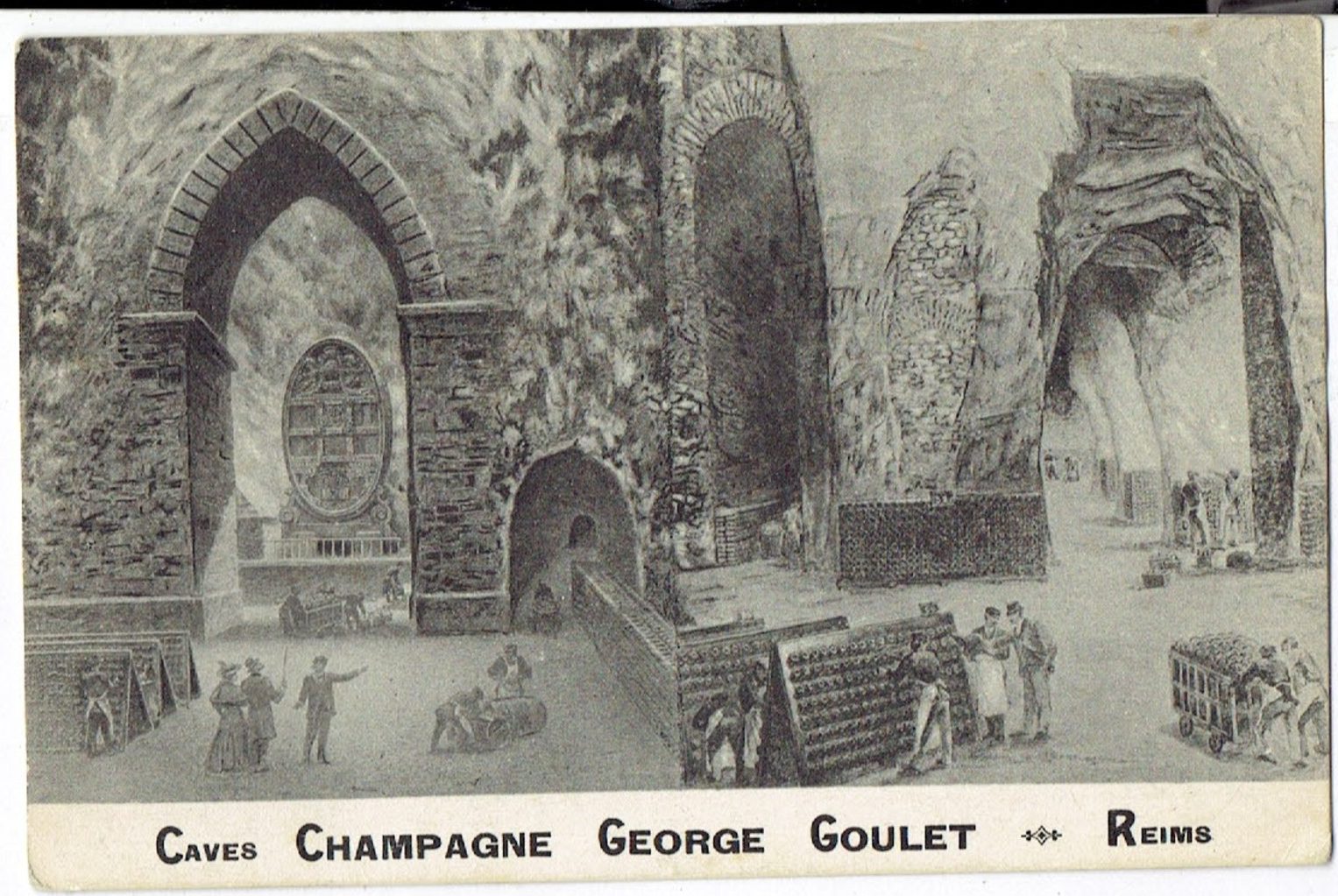

The pliant chalk of the champagne region had been quarried by the occupying Romans as far back as the 1st century AD. They left behind vast, caverns dug out of the chalk, known as les crayères; they proved to be the ideal temperature to store and mature champagne.

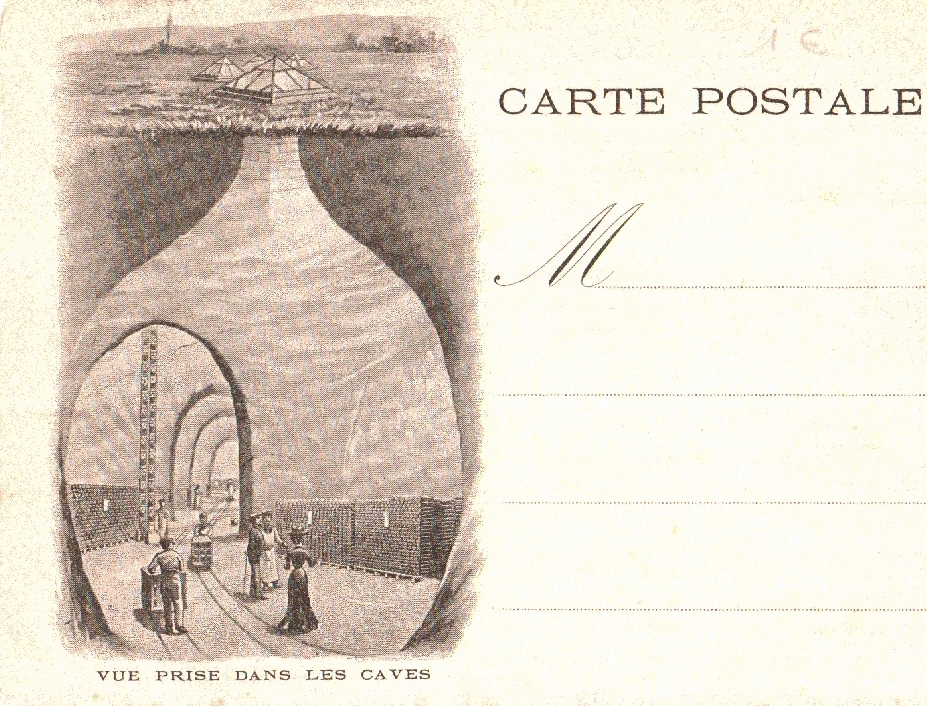

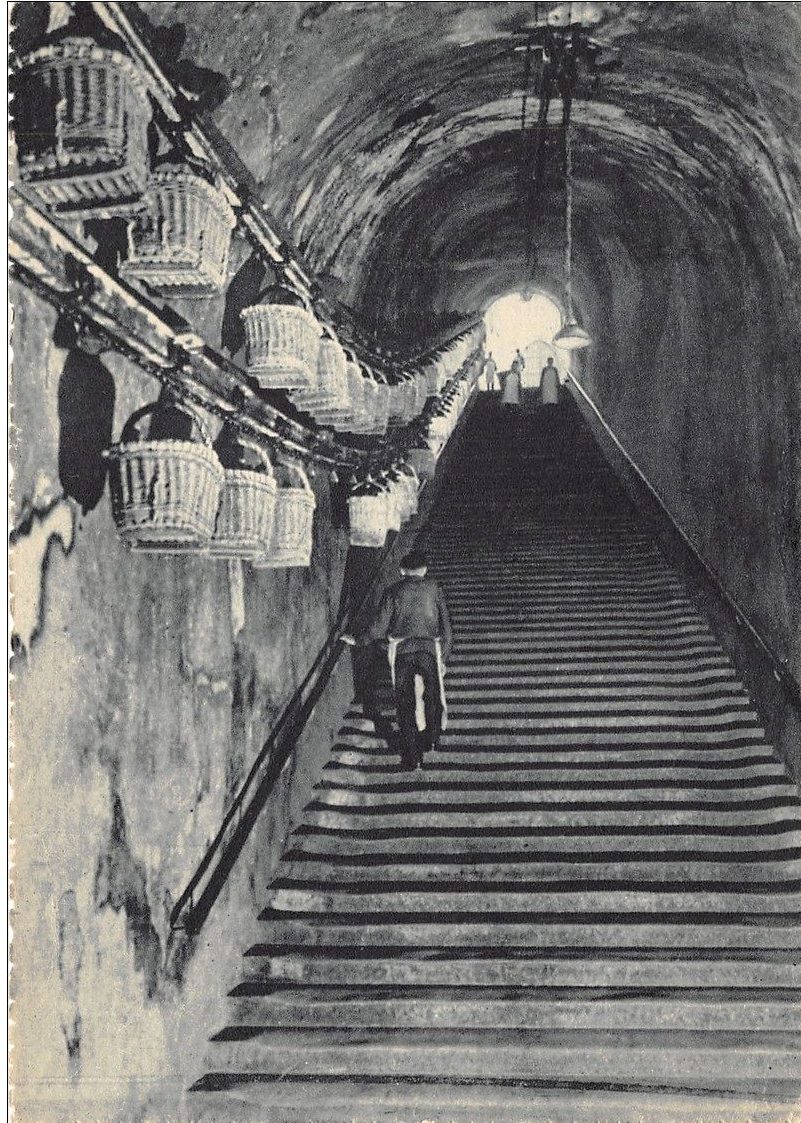

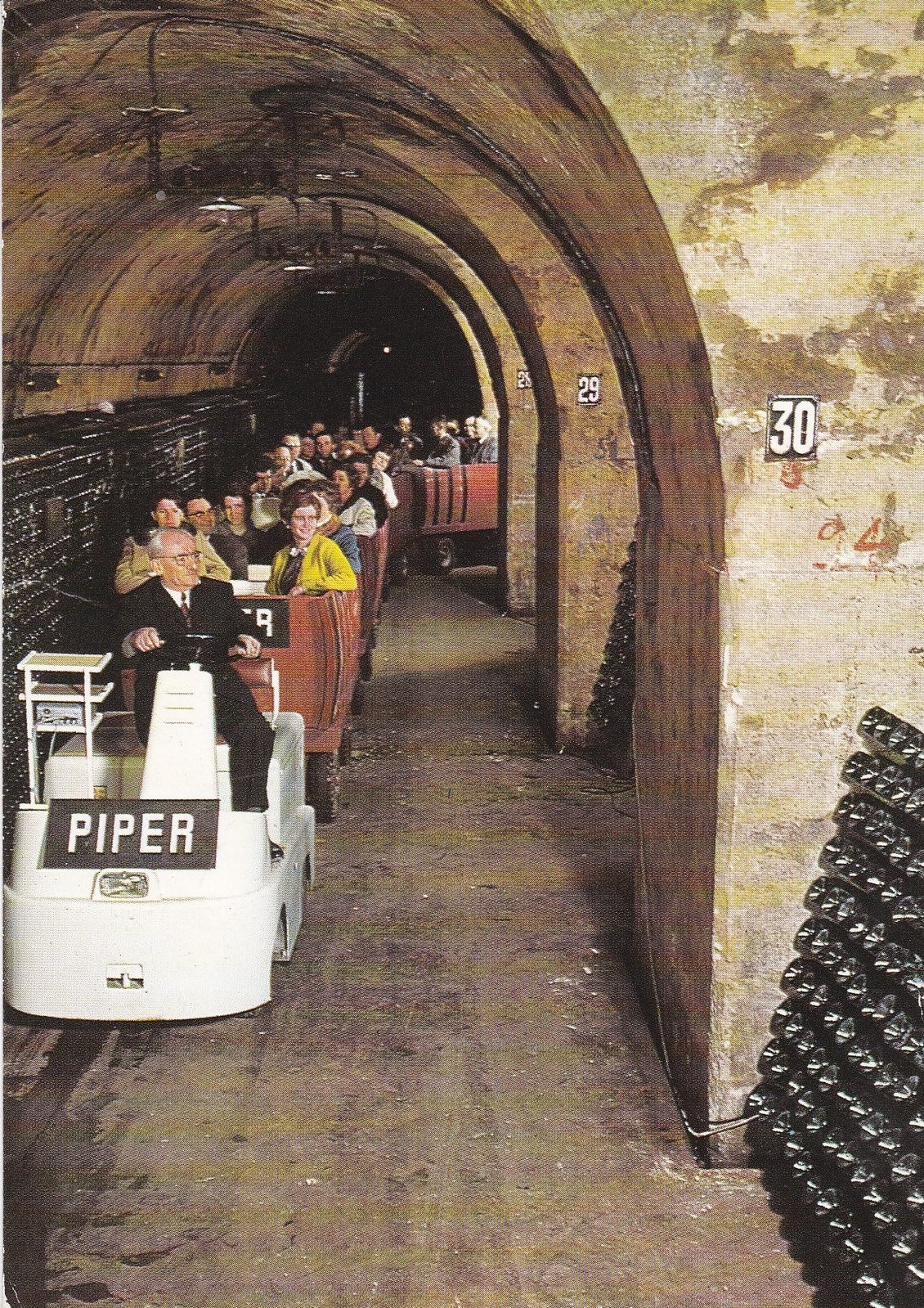

We are standing at the entrance to an improbably steep staircase that heads straight underground. Carved into the rock and dimly lit, it appears to go on forever. This is one of the entrances to the Pommery subterranean caves and wine cellars, where many of the desperate citizens of Reims sought refuge in 1914.

The complex system of ancient caves running underneath Pommery is incredible. But the story of the house which owns and uses them is perhaps more so; for Pommery, the vineyard that produced the first ever Brut champagne, was run, unusually for the time, by a woman.

Madame Jean Alexandrine Louise Pommery took control of the champagne house upon the death of her husband in 1860. She set upon an astonishing building project, connecting the old chalk quarries with nearly 18 miles of tunnels, vaults and underground passageways, that would meet at vast cavern plazas. The walls were decorated with immense bas-relief sculptures celebrating wine and the god Bacchus, created by the artist Gustave Navlet.

The 116 step staircase was the only connection between the underground world and the vineyards outside.

In 1914, as the bombardments increased in their ferocity, Reims was caught in a firestorm. Reporter Raymond G. Carroll sent a cable dispatch to his newspaper, the New York Sun. Reims, he wrote, “is robbed of all form of life. Theatres torn to their foundations, cafés wrecked, department stores demolished……French barbed wire still ran though its streets.”

Another war correspondent, Edward Alexander Powell, reported, “I shall be accused of imagination and exaggeration, whereas the truth is that no one could imagine, much less exaggerate, the horrors that I saw upon those rolling, chalky plains.”

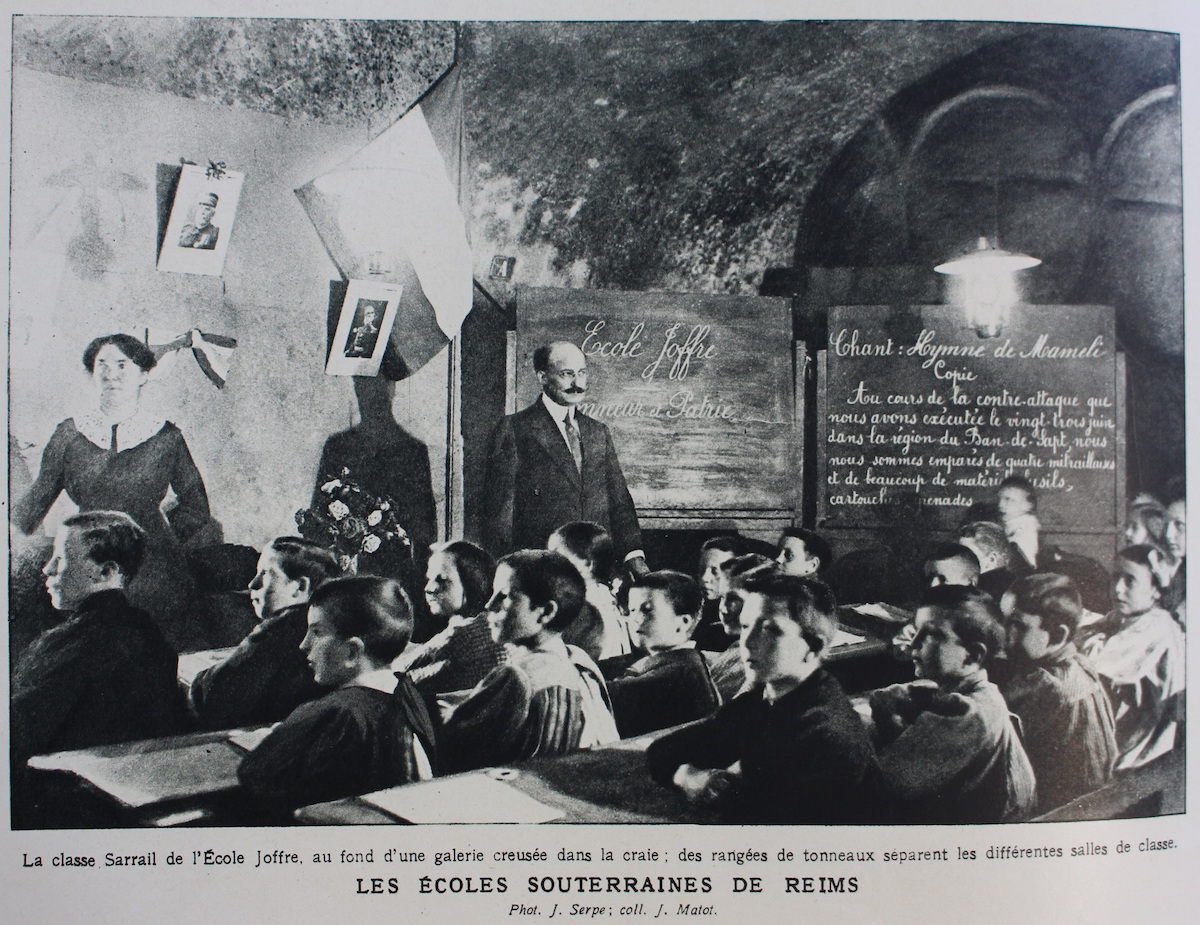

More and more civilians began to descend the steep staircase, as Madame Pommery’s caves swiftly became an underground city. “The teacher, the children and all their families lived underground. So dangerous was it to go on the open ground near the entrance of the caves, that the children were absolutely forbidden to go out”, wrote eye witness Francis Rolt-Wheeler in the account, ‘Heroes of the Ruins’. “The part of the caves devoted to the school was divided into three parts, one for the class itself, one for a playground, and one for a gymnasium. Three hours of gymnastics were held daily so that the children, deprived of fresh air and exercise, might not fall ill.”

Life in the twilight world underneath the Pommery vineyards tried to carry on as normal.

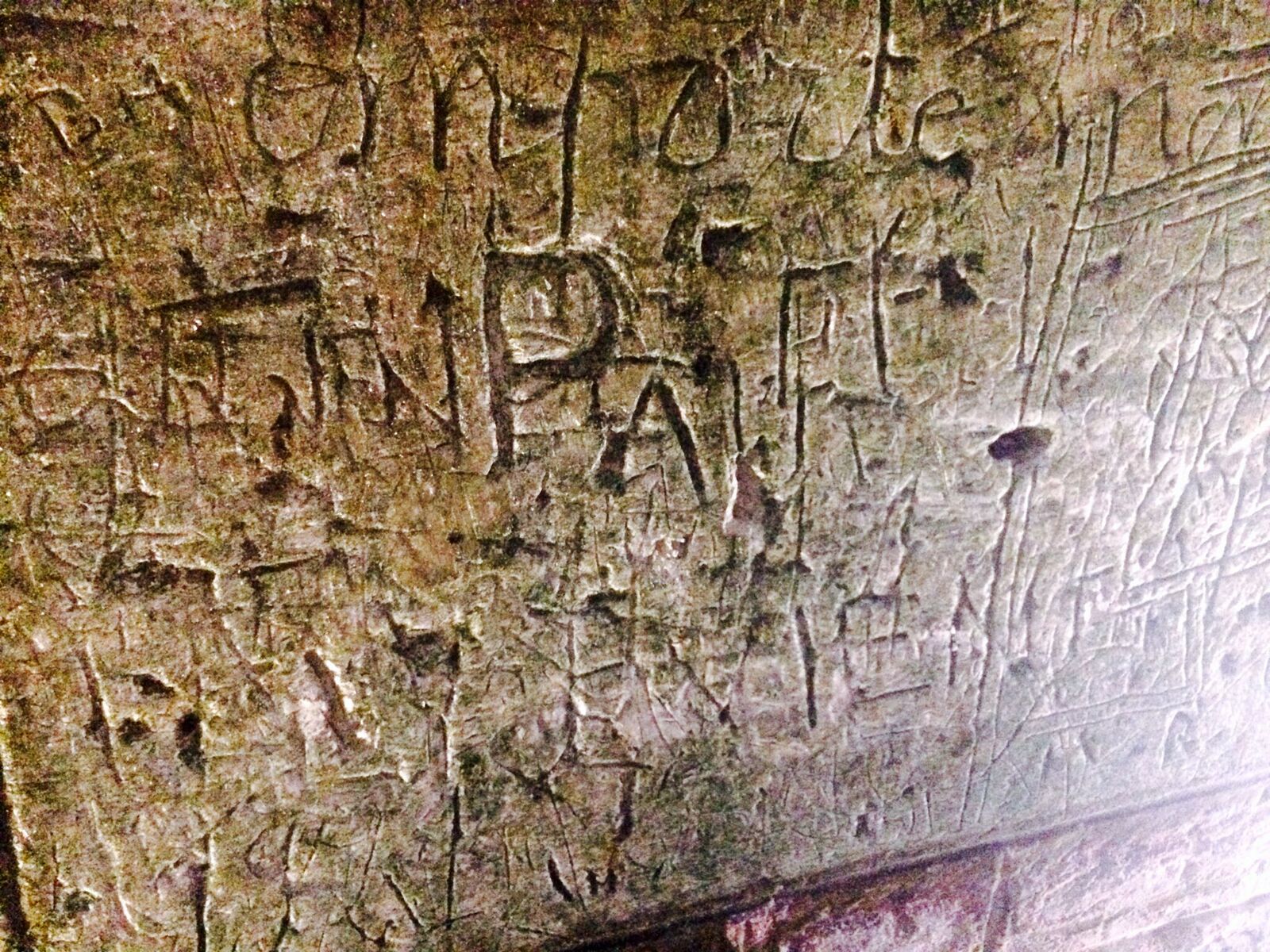

Walking today, through the never-ending labyrinth of dimly tunnels that suddenly open out into caves, there are still eerie traces of the war. Doodles and names etched into the chalk, altars from old churches, ancient steps dating back to Roman times, and cartoonish faces carved into the walls. “The tunnel next door to us was used as a chapel” continued Rolt-Wheeler. “It was filled almost every Sunday, when the bombardment was not too terrifying. The seats were cases of champagne.”

These old remnants from the war rest along side tens of thousands of sleeping bottles of dusty champagne that are still regularly turned by hand. One writer visiting the crayères likened the experience to “tiptoeing through a room of sleeping toddlers.”

With most of the men away fighting at the front, the underground world was largely home to the elderly, women and children. Over at Ruinart, one of the oldest wineries in Champagne, there was a similar network of spectacular, ancient caves that were transformed into vital living quarters during World War One. There, eight miles of tunnels connected twenty four crayères over 125 feet below ground.

The walls were, “covered with straw-matting, on which a grey wallpaper had been pasted. From the ruins of houses, potted plants had been brought – frail things which had escaped the destruction that toppled down the stone buildings in which they had been. The plants suffered from a lack of sunlight, but gave a touch of green nonetheless.” (Rolt-Wheeler)

In the half-light world underneath Mumm’s chateau, the subterranean school was named for Marshall Joffre, commander-in-chief of the French army. “The desks and stools, many of them scratched by shell, were gathered from the ruins of the demolished schools.” (R-W)

Incredibly in 1914, there was still a champagne harvest, the last until after the war. The grapes were harvested by children, their mothers and grandparents. “At the beginning, it was a bit of fun; a game, to squeeze perpendicularly through vines and bring back the grapes without exposing themselves at the end of rows.” In 2013, Sotheby’s sold at auction, three two-bottle lots of 1914 Moet & Chandon vintage, for nearly $25,000. The price though pales compared to the human cost: by October, 1914, when the last accessible grapes had been picked, more than twenty petites enfants had been killed by shells.

Today, most of the houses in Champagne offer tastings and tours of their incredible underground cellars. Bottles of champagne have long been associated with celebrations and toasts. But exploring the hidden, underground world beneath places like Pommery, you can discover the secret history of the desperate people who lived here for years, whilst their homes above ground were steadily destroyed.