© Jean Depara

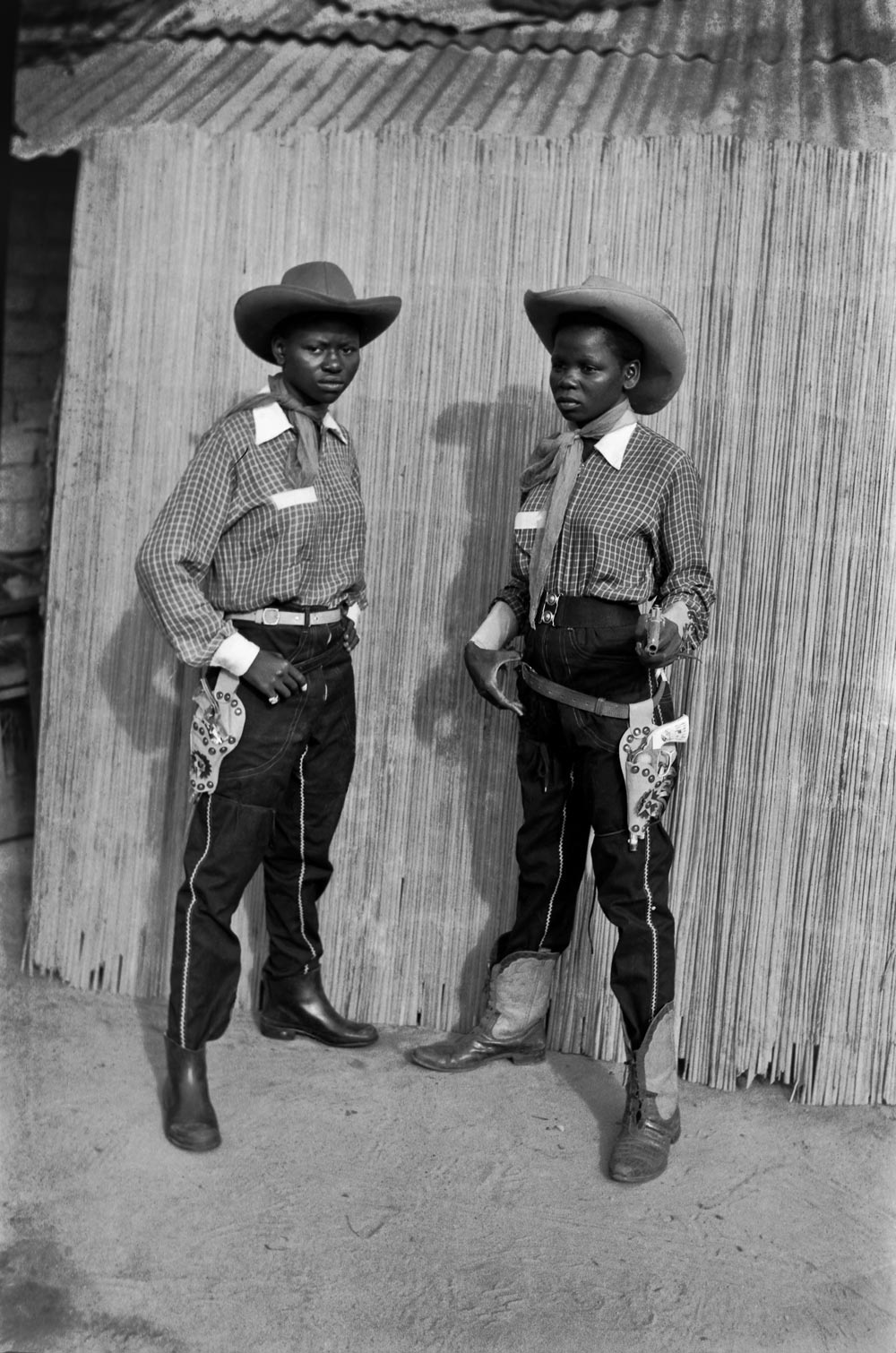

We’ve met the dapper dandies of the Congo, but today let’s discover yet another subculture from the same corner of Africa, forgotten in the folds of time. In the 1950s, when the Congo still belonged to the Belgium colonialists and the capital of Kinshasa was known as Léopoldville, it was a difficult place to be a kid to say the least. Infantilized by the colonial class, education didn’t go beyond primary school level and Kinshasa’s youth found themselves looking to western culture for role models and inspiration– in particular, American cowboy movies.

© Jean Depara

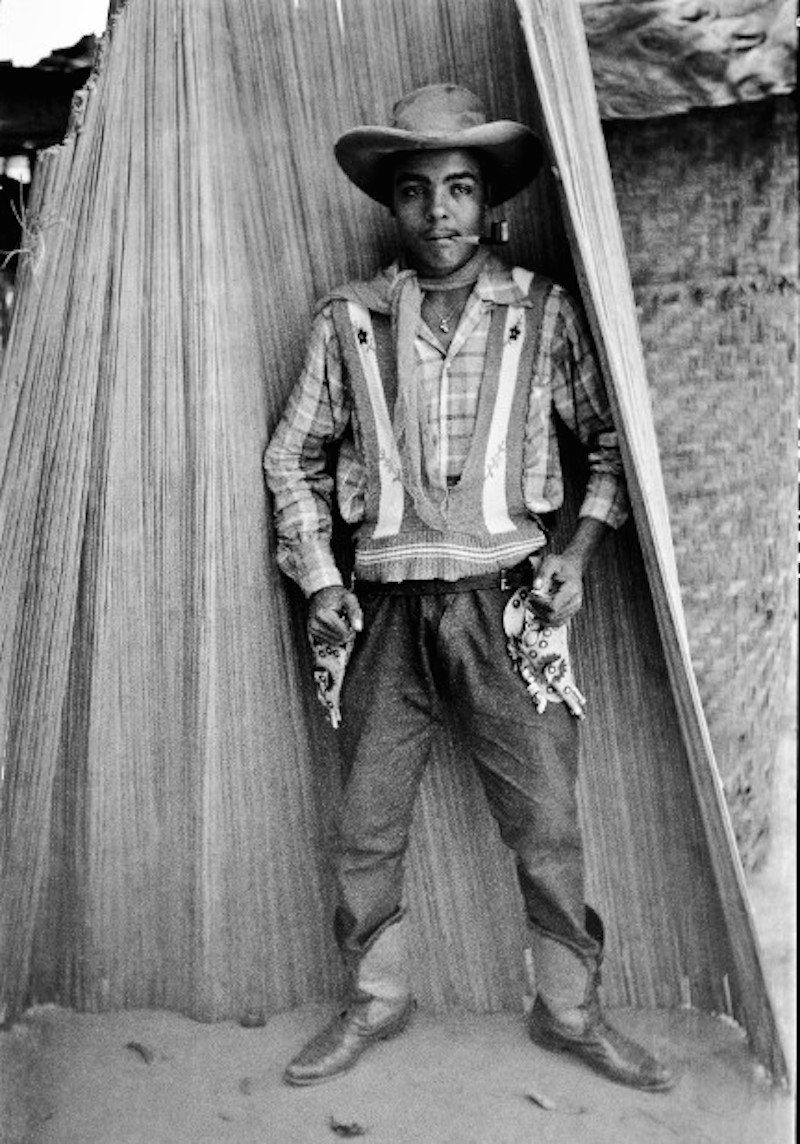

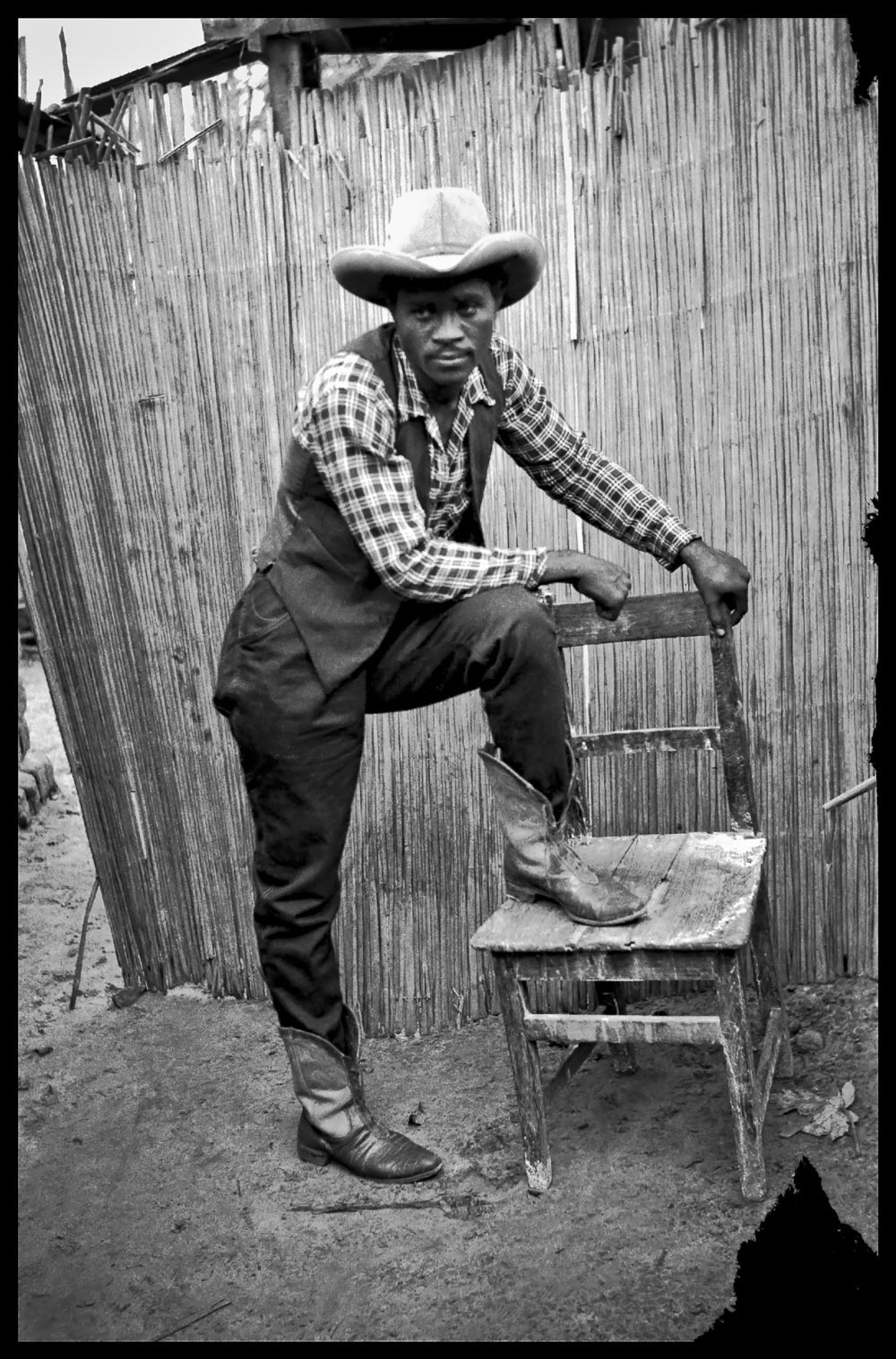

I’m currently eagerly awaiting my copy of Tropical Cowboys the only existing study and book on the young urban (mostly) male gangs known as “Bills” or “Yankees” in mid-century Kinshasa. Written by Professor Didier Gondola, the book includes photographs by Jean Depara, a shoemaker in Kinshasa who documented the rise of pop culture influence in the Congo with his Adox camera. Depara’s photographs may very well be the only evidence of this lost subculture of Kinshasa’s cowboys.

© Jean Depara

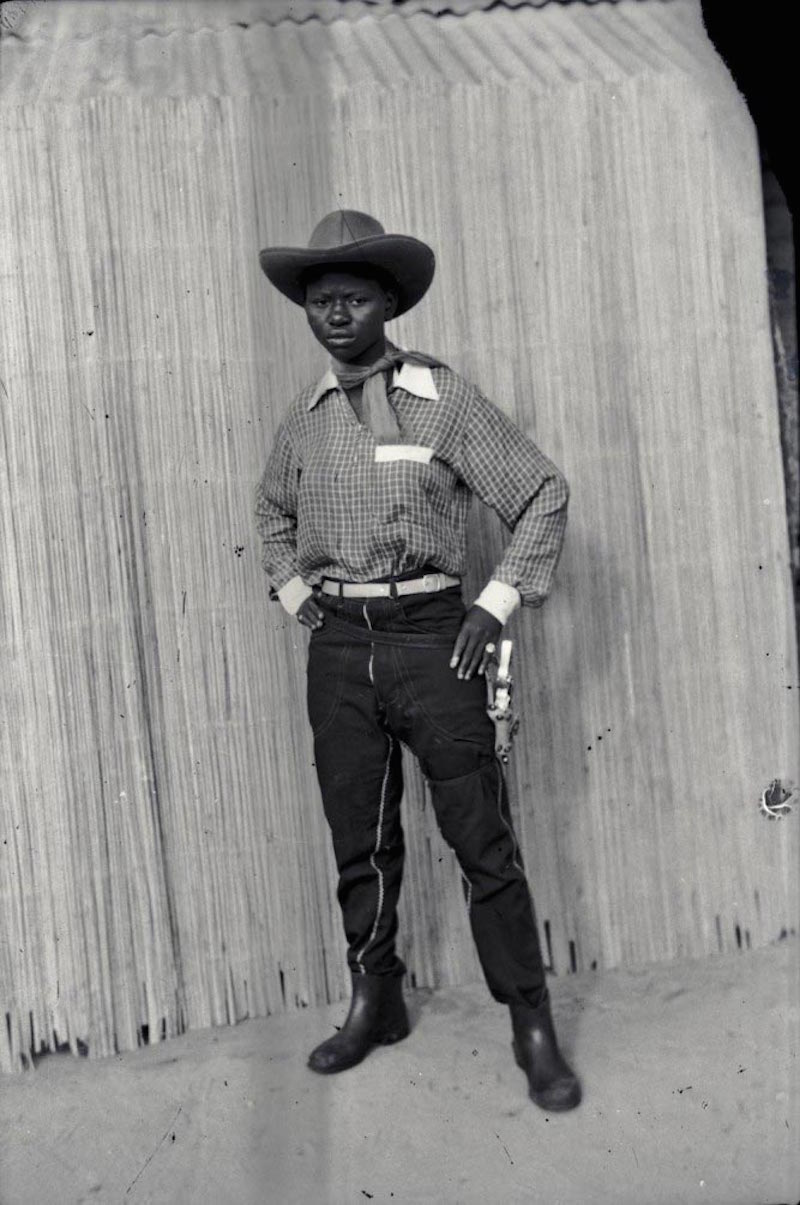

These boys were “on a quest for manhood” according to Gondola, who believes their street culture became a backdrop for Congo Zaire’s emergence as an independent nation”. By identifying with these heroes of the American West, they were often criticised for abandoning tradition in favour of foreign inappropriate foreign ideas; labelled as victims of cultural imperialism. However, Gondola argues these Congolese cowboys chose their heroes wisely.

The cowboy was a winner– a fighter. “Young people, when they’re watching Manichean movies, will always side with the victors,” he explains. “They’re never going to side with the people who are being destroyed, being defeated; being stripped of their masculinity.” Nor were they going to choose the imperialist officers or the white priests of a disintegrating colonial society as their heroes. To assert their rebellion, the cowboy was the perfect idol.

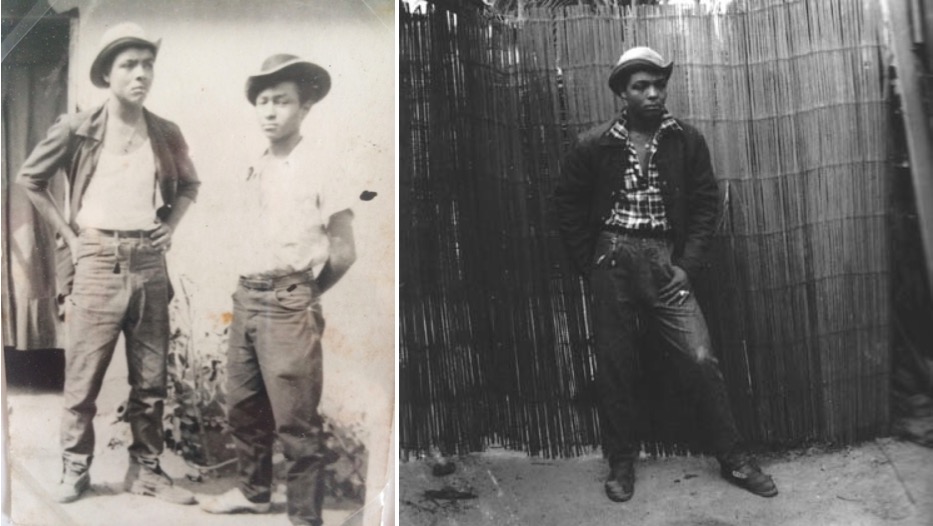

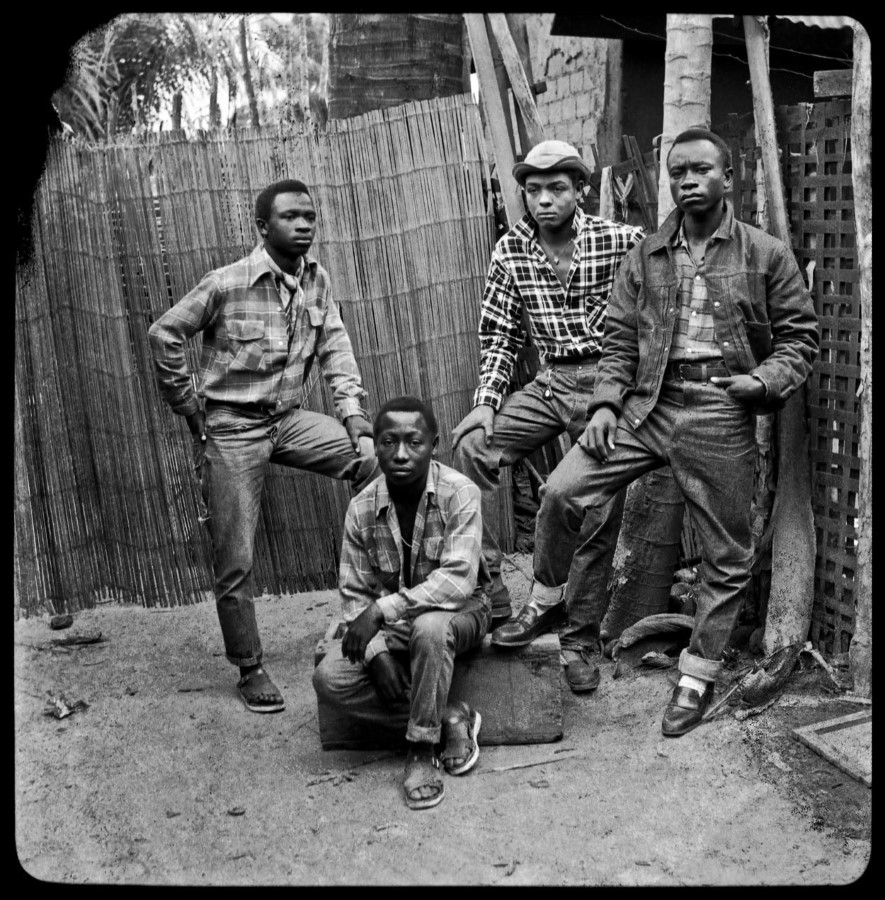

© Jean Depara

They sourced their western outfits from Belgium and had family members abroad send them hats, boots and plaid shirts.

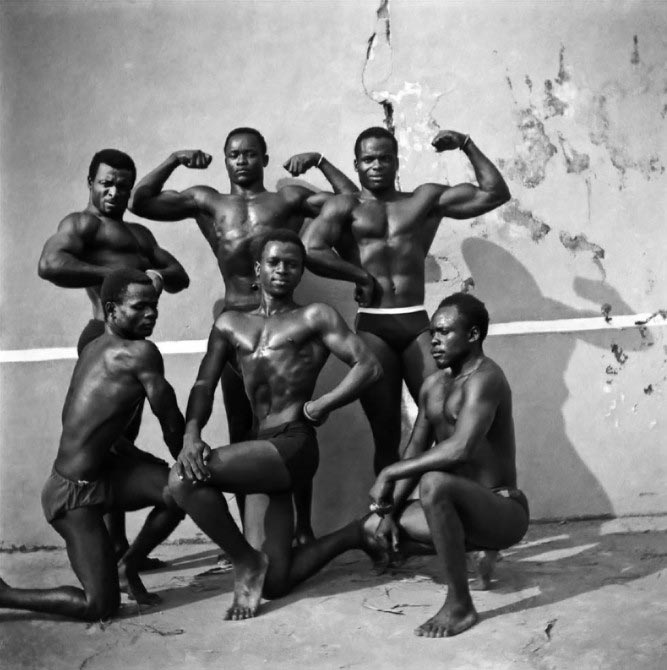

© Jean Depara

Even body building was also an important part of a young man’s regime to complete the macho look.

© Jean Depara

Initially the working-class neighbourhoods, the Bills and the Yankees played the role of “big brother” to the younger boys, however, the Congolese cowboys soon got carried away with their “Robin Hood” roles in society and later swung into delinquency and violent behaviour which lead to their downfall. Many groups became more notorious for their internal territorial disputes and the sexual abuse of women between gangs.

© Jean Depara

But when the riots broke out across the city in 1959, the Bills were at the forefront, fighting for their independence. After the rebellion, many of Kinshasa’s Yankees went on to have careers in politics, in the army or in sports and even music. Ironically, it was a Belgian missionary in the mid-1960s who put an end to the lost cowboys when he went as far as identifying Christ as a big “Bill” himself, convincing the young cowboys to change their ways and retire their cowboy boots in the post-colonial period.

Meta, one of the female Bills (with a toy gun) © Jean Depara

“It wasn’t really the politicians or the trade unions that spearheaded the fall of the colonial regime,” says Gondola. “It was the young people … the young Bills and Yankees … they are the ones responsible for the first major insurrection in Kinshasa. The country owes a debt to them, but most people don’t know that.”