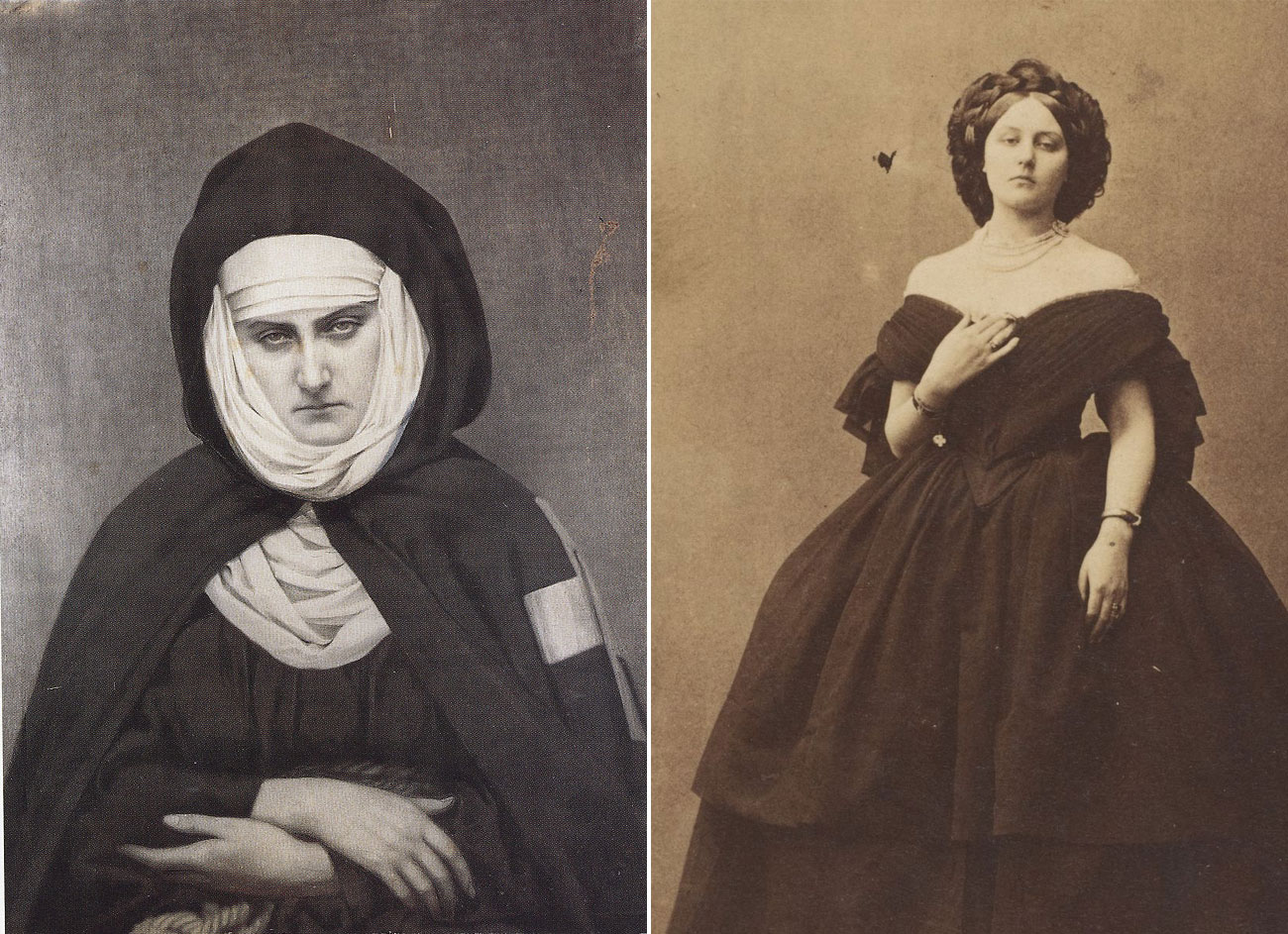

She wasn’t the most likeable character of her time. Once rumoured to be the most beautiful woman in 19th century Europe, a queen of both style and drama; model, mistress, self-appointed muse, narcissist; if there’s one thing to know about the Italian Countess de Castiglione – it’s that she was seriously vain. Shipped off to Paris in 1856 to compete for the affection of the reigning King Napoleon III, she wasted no time weaving herself into a highly scandalous affair with the crown, all the while cultivating her own celebrity through hundreds of elaborate, self-directed photo shoots. At a time when photography was still in its infancy, the Countess had a body of work that could be compared to Kim Kardashian’s selfie collection. It was her vanity and obsession with her own beauty that came to define her entire lifestyle, around which her status, identity, and ultimately her demise, revolved. A cautionary tale of a woman who thought her beauty would last forever…

Introduced to French society as a mysterious chess piece, she existed as a promiscuous wager aimed at securing a profitable rapport between the French and Italian empires. Virginia Oldoini, Countess of Castiglione was married by the age of 17 to an Italian count, but upon the command of her calculating and powerful cousin, the Count of Cavour, she was secretly assigned the task of seducing the Emperor of France, right under the nose of her husband.

The Countess of course succeeded, and her newly-found influence and esteem earned her invitation to top-secret meetings with international leaders, her contribution credited for the enduring security of numerous Western nations. When she was called to meet the Prince of Prussia, She may have even convinced Otto von Bismarck to spare Paris from a Prussian occupation after the Franco-Prussian War.

Virginia Oldoini, however, was quick to retreat from the intelligence, wit and feminine strength bestowed upon her character, instead becoming absorbed by intense vanity for the duration of both her public and private life.

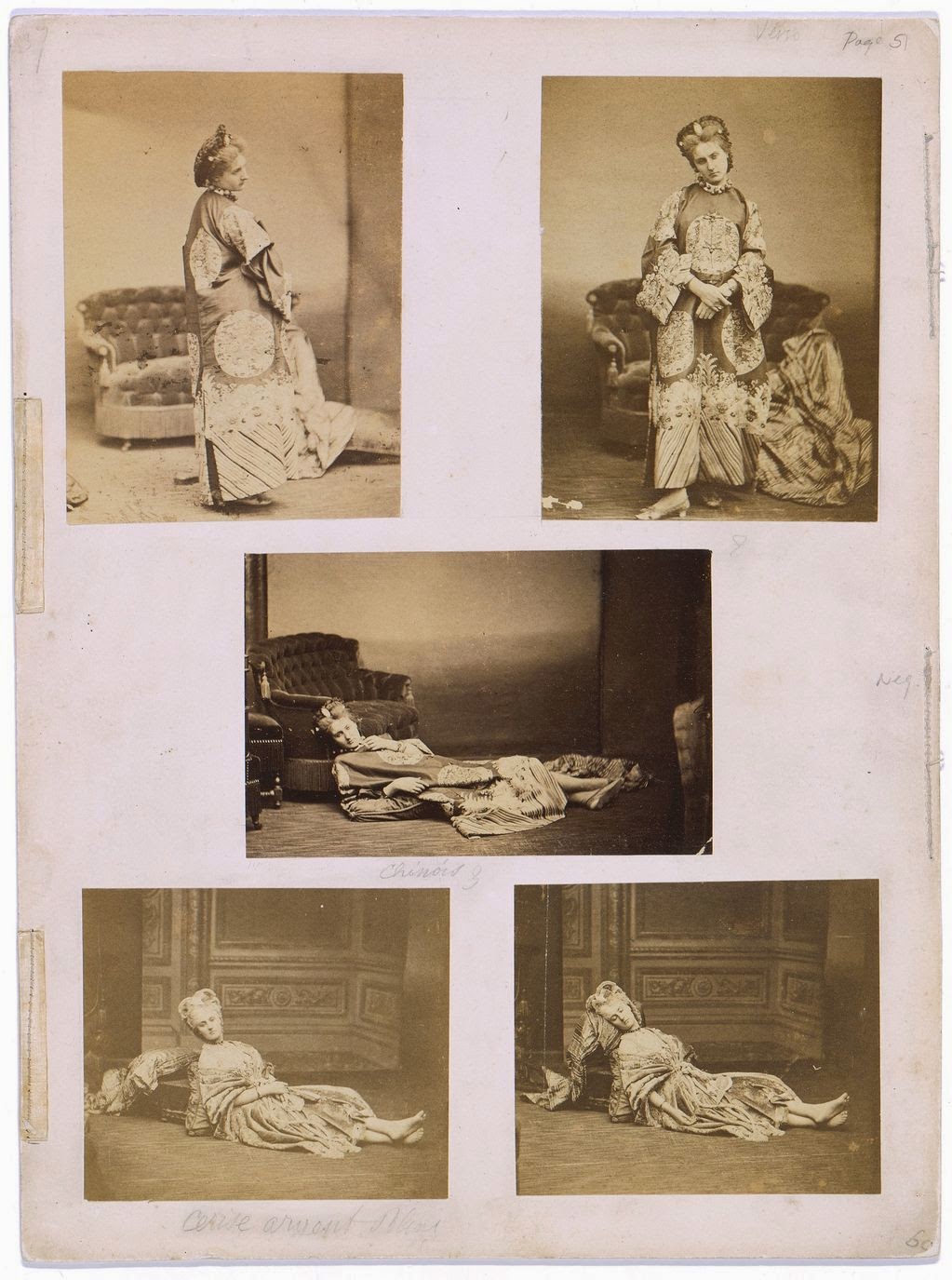

La Castiglione’s time in Paris was marked by an intense, bordering on narcissistic, obsession with her image. Intrigued by the relatively uncharted photographic medium, she independently approached the studio of Mayer & Pierson, whose atelier on the Boulevard des Capucines was worshipped by the highest strata of Parisian society. This relationship ultimately produced over 400 portraits, a quantity unheard of for the time, due to the sheer experimental, laborious and economic investment (of her husband) required to realize a single gelatin print.

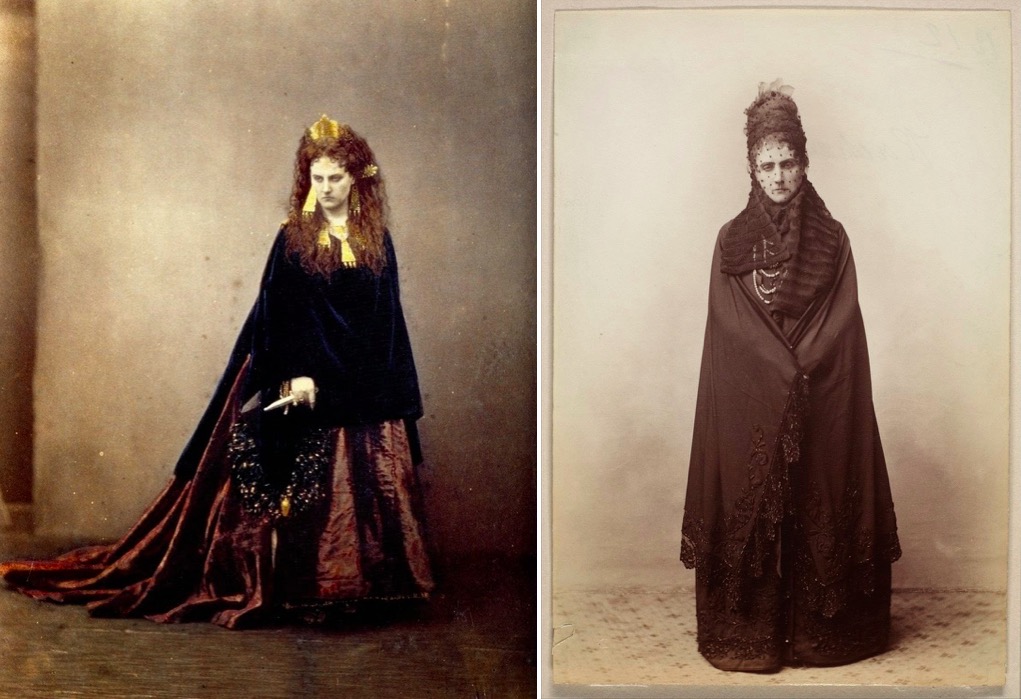

Devoted to immortalising the beauty of her prosperous youth, she staged a series of intricate scenes meant to evoke both exact and symbolic moments from her life. Each image was accentuated by lavish costumes, staging and poses which were extremely innovative, non-traditional and surreal; a daring artistic trait that added dimension to the air of mystery surrounding her identity.

From behind the veil of vanity with which she hid, she was keen to direct these photoshoots in order to achieve a level of perfection that only her mind was capable of curating.

Despite the divine facade; her porcelain-like exterior and theatrical style many women envied and strived to emulate; the Countess was universally disliked. She had few friends and almost never spoke to women. Her husband had left her after just three years of marriage, returning to Italy furious and bankrupt.

Many first-hand accounts of Castiglione describe an arrogant and “disturbing” character, noting that “her motives were unclear”. Even if the Countess was a pioneer of early photography or an artist in her own right, no one particularly felt like giving her the credit for it.

As her precious looks faded and she began to age, Castiglione locked herself away from all eyes, including her own. During this period of mourning that would extend to the terminus of her life, she became a recluse within her apartment at Place Vendôme, one whose mirrors had been banished and whose every surface dripped in funeral black.

She would only leave the apartment at night, occasionally returning to her photo studio to attempt another photo project, which would later be described by critics as even more morbid and deranged than her earlier portraits.

She died in Paris at the age of sixty two and was given an unremarkable tombstone in the Père Lachaise Cemetery. Before her death, she had been valiantly trying to land herself an exhibit of her photographs at the 1900 World Exposition, a show that never was, entitled “The most Beautiful Woman of the Century.”