Fordlândia © Tom Flanagan

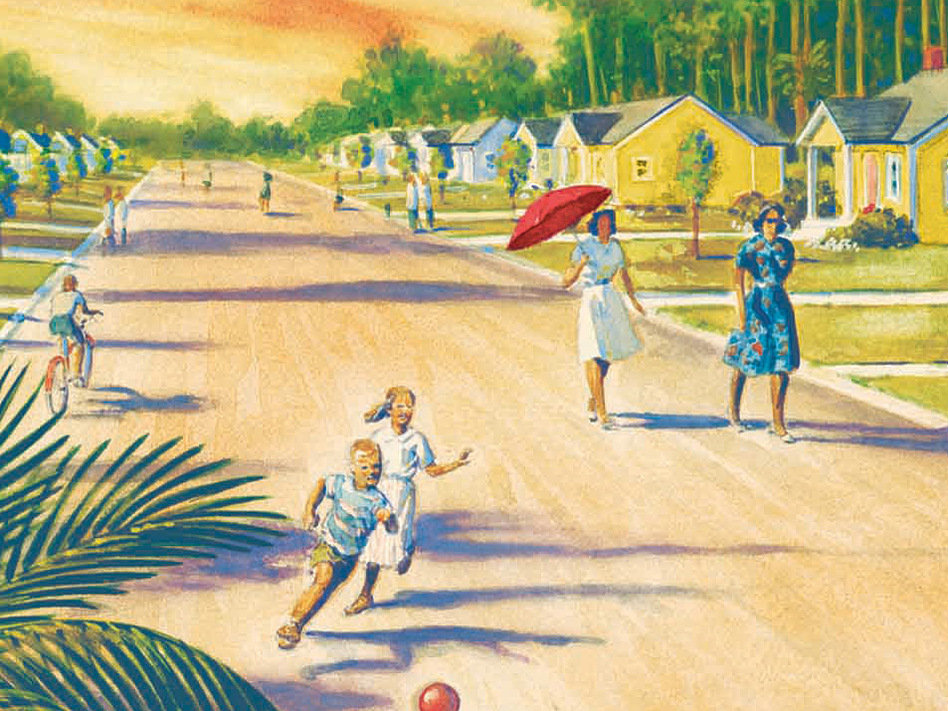

Typical American houses and mid-western streets sprang up as fast as the jungle could be stripped and cleared. Fordlândia– foreign outpost for one of the world’s largest and most profitable companies, dream of an American business magnate, and one of the worst ideas Henry Ford ever had.

It was the motor industry giant’s epic jungle adventure, an experiment at creating a Midwestern-style company town in the Amazon. After only six years of its foundation in 1928, the industrial town intended to be inhabited by 10,000 people, was abandoned, leaving behind the ghosts of a great enterprise. This is all that remains of Henry Ford’s American dream, 5,000 miles away from home. Welcome to Fordlândia…

In 1928, two merchant ships arrived on the east banks of the Tapajós river, loaded with American goods. It carried all the equipment that a prefabricated American town could possibly need, from door knobs to street lights and little red fire hydrants.

Fordlândia was intended to secure a source of cultivated rubber for the Ford Motor Company. Ford hated being at the mercy of English and Dutch rubber barons and refused to rely on the European monopoly that controlled the industry in the early 20th century. He needed a considerable about of rubber for his car tyres, so he decided to cultivate his own in the Amazon’s rainforest, where he negotiated a deal with the Brazilian government that granted him 10,000 km2 of land in exchange for a 9% share in the profits generated.

Unfortunately for him, none of Ford’s managers that he sent to the jungle had any knowledge of tropical agriculture….

The town was, founded under the name of Fordlândia, boasting a utopian array of American amenities, including a pristine golf course, movie theatre, swimming pools, dance halls, a hotel, school, playgrounds and a library.

Henry Ford is not remembered as one of the most sympathetic figures in American history. His strong anti-semitic vitriol was no secret and he notoriously continued doing business with Nazi Germany well after the United States entered World War II. His new town was essentially split into two– a planned community with one area for the American managers, known as the American village, and another designated to the Brazilian workers.

He was very particular about Fordlândia operating like a real mid-Western American town, ensuring that his resident Brazilian workers lived in the American-style housing, complete with white picket fences, and even insisting that they ate American-style food– an unfamiliar diet of oatmeal, canned peaches and brown rice.

Ford wasn’t a fan of the Jazz Age either, and saw the town as an opportunity to recreate America as he had always imagined it. A strict set of rules imposed by the managers. No alcohol, no tobacco, no women inside workers houses, not even football was allowed within the town. Inspectors came to the workers housing to check they were living according to their American standards that had been forced upon them.

Ironically in keeping with the American way of life, contraband goods were often smuggled into town to get around the American-imposed prohibition. The locals used large fruits like watermelons to sneak in alcohol and tobacco, and when they could, they would take a boat upstream to an “”Island of Innocence” where they could find bars, nightclubs and brothels.

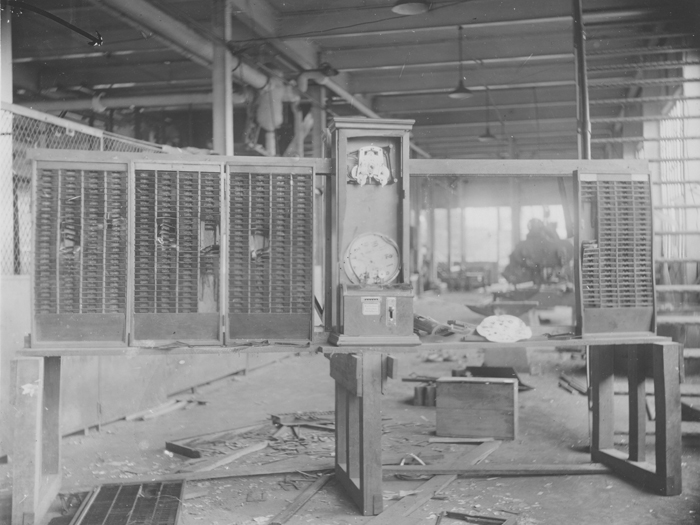

Eventually, one sweltering hot day in 1930, after working under the tropical sun, the Brazilians rioted in the town’s cafeteria. They smashed company property, cut the plantation’s electricity and telegraph wires and chased the American managers into the jungle, along with town cook, where they hid for days, awaiting the arrival of the Brazilian Army. The workers eventually went back to work once an agreement had been reached on the type of food they would be served at the cafeteria. But Fordlândia had much bigger problems on the horizon.

From very the beginning, Ford’s men, (the ones that knew nothing about tropical agriculture), had planted seeds of questionable value. It wasn’t long before leaf blight was ravaging the plantation, but still Ford powered ahead with his American outpost, intent on proving he didn’t need the Europeans.

The old cemetery, destroyed by floods © Babak Fakhamzadeh

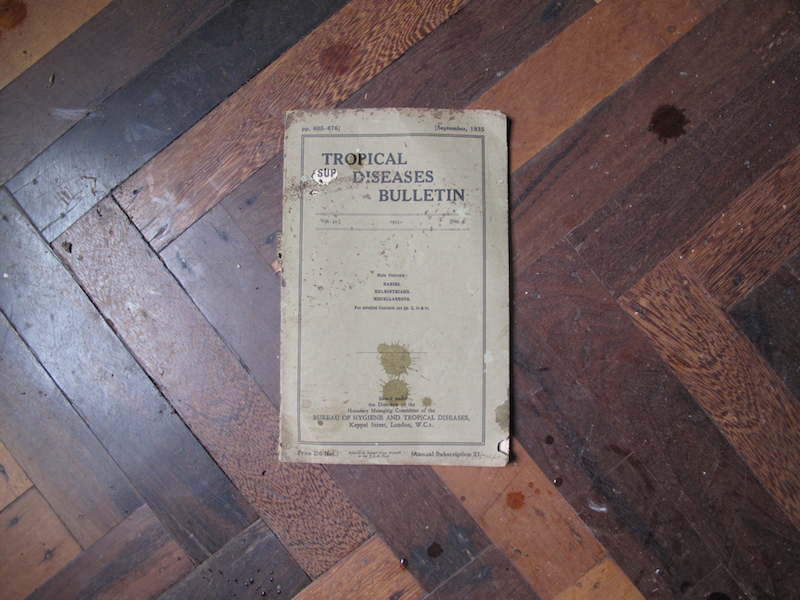

Brazil’s coveted rubber tree, the Hevea brasiliensis, traditionally grew in the wild, spaced apart from other trees as a protection against diseases. In Fordlândia, the plantation’s trees were cramped together, making them easy prey for plagues and infestations. Not only could their trees not hack it, but the Americans themselves were not faring well. Many managers suffered nervous breakdowns, died in accidents or lost family members to tropical fever.

In 1934, the Americans began to admit their defeat and decided to relocate to another stretch of land Ford had purchased downstream. Fordlândia was abandoned in 1934. Furniture, silverware and even clothes were all left behind inside the houses.

Fordlândia as it was:

View of employee housing, Fordlandia, ca. 1933.

Americans posing for photos with local families

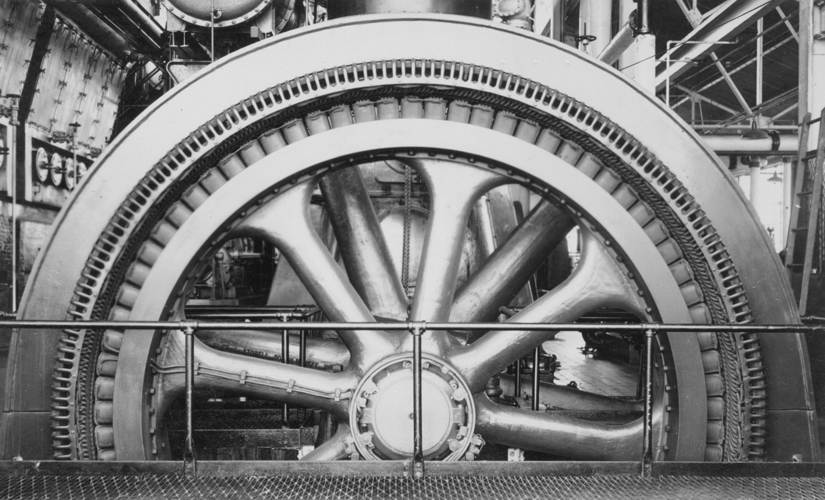

General Electric generator in Fordlandia’s powerhouse, ca. 1933.

A Ford employee standing next to a newly-planted rubber tree

By the end of World War II, Ford’s second town, Belterra, had been also been abandoned as it became clear there was no profit to be made cultivating trees in or anywhere around Fordlândia. By 1945, the Japanese market had created a new synthetic rubber, and Ford’s huge South American investment dried up overnight without producing any rubber for his cars. The vast land purchased by the motor company was sold back to the Brazilian Government at a loss of over $208 million in the current day value.

Main boulevard

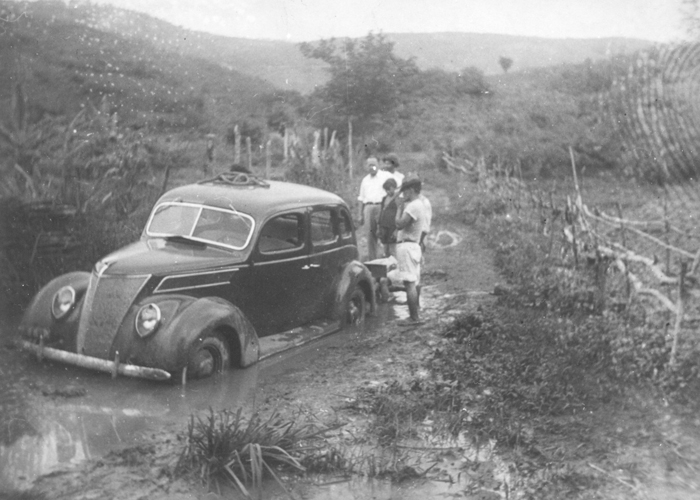

A Ford automobile, stuck in the mud

Payday at Fordlãndia

Clearing trees at Fordlandia, 1933

Hospital ward

Fordlandia time clock, destroyed in the riot of December 1930.

Fordlandia dance hall with movie screen

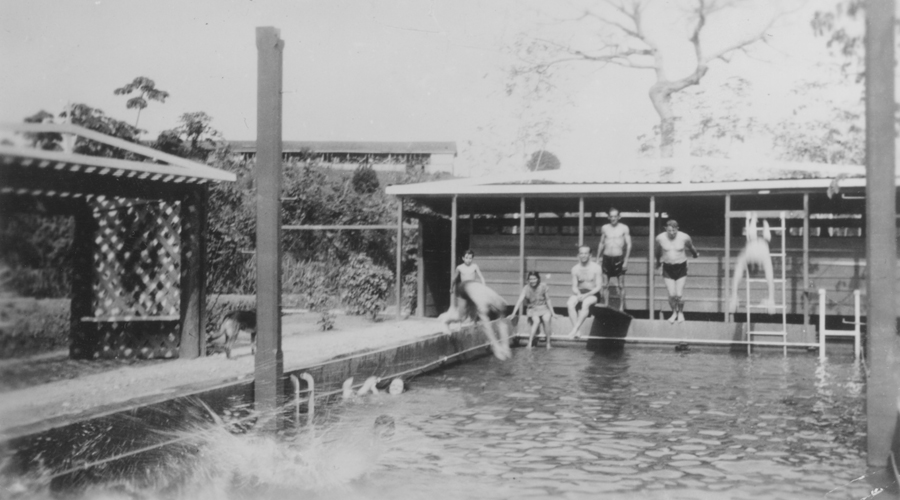

Swimming pool for American Ford employees © Henry Ford Archives

Henry Ford had never never once visited Fordlândia.

Resident of Fordlãndia today © Mixer Produtora

The Brazilian government tried to salvage something of the isolated outpost, but eventually they too gave up and abandoned Fordlândia. Squatters moved into the American bungalows on Palm Avenue and it became a looter’s paradise as the jungle reclaimed its land. Despite no basic services or supplies to the area, the town was still inhabited by ex-workers of Ford. More returned after the new millenium in search of housing and today, Fordlândia is home to nearly 2,000 people.

© Romypocz

All the American buildings remain intact except for the hospital, which was destroyed by looters. While Ford may not have been able to make rubber, he sure knew how to make infrastructure that lasts.

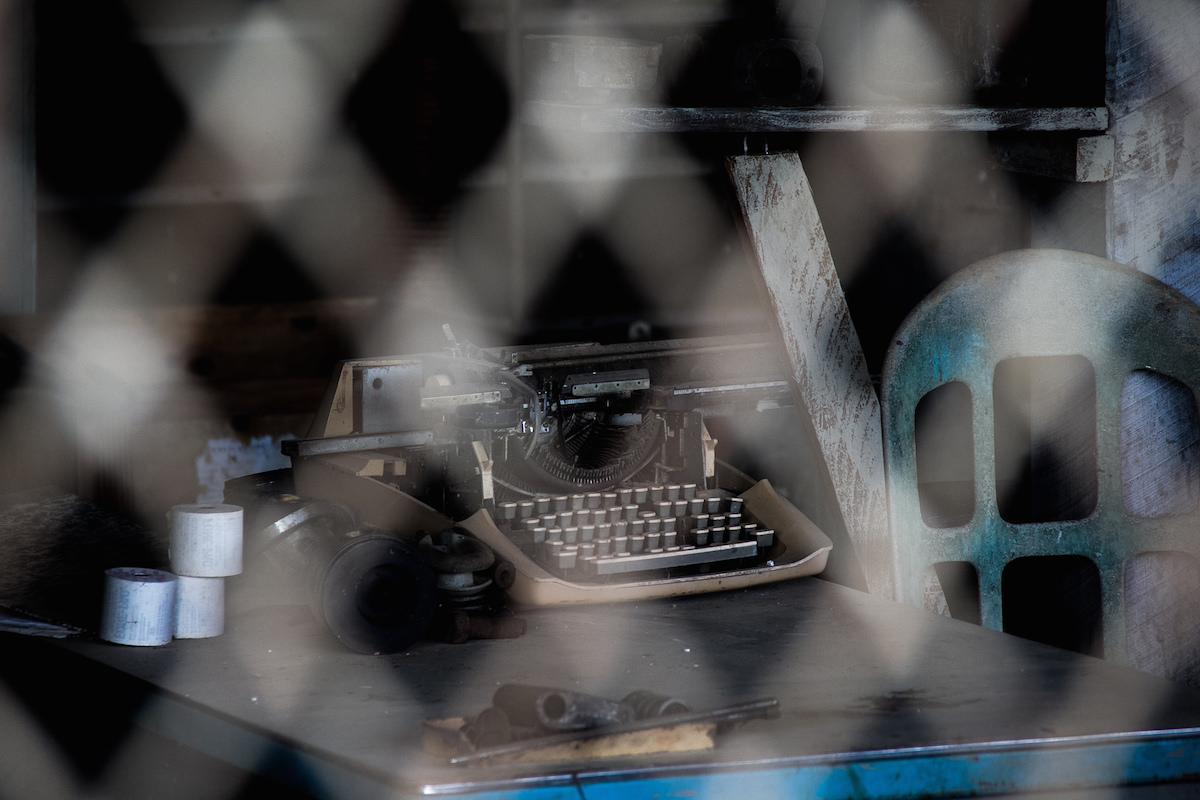

Helped in part by the squatters that occupied and protected the buildings following the town’s desertion, most of the equipment brought to Fordlândia by merchant ship in 1928 still remains, from the light fixtures in the manager’s houses to the fire hydrants, now covered in jungle vines.

Much of the original US machinery can still be found in the three-storey workshop where they manufactured parts for the plantation’s machinery, and the building now acts as a sort of warehouse storing all kinds of Fordlândia relics, including hospital beds, cafeteria items and even an old X-ray machine. There has been some controversy over how the hospital X-ray machines were dismantled and reports of boxes containing radioactive material left behind that may have contaminated the local area.

The 50-meter high water tower, built in Michigan and still fully operational, is seen as the symbol of Fordlândia’s origins– a reminder of that time the great industrial giant, father of the automobile, tried to bring America to the Amazonian jungle.