The Players © mcny.org

Old, private members’ clubs can tend to be stuffy, conservative affairs. One of the last, living remnants of 19th century gentleman’s society, they bring to mind images of leather backed armchairs, and smoke filled rooms, where the respectable members sip snifters of brandy. But hidden away in New York, there is a certain club that stands alone. For the Players is very much vibrant; created as a private club for actors, writers, musicians and lovers of the arts, the jovial atmosphere is as fun loving, as when it first opened on New Year’s Eve in 1888.

The Players is much more than just a swish private clubhouse; for within it’s elegant and cosy confines, you will discover a remarkable, living museum full of secrets. It contains an unparalleled collection theatrical artifacts, costumes and weapons, many over a century old. There are even human skulls that were once used as props. Discreet draws open to display Victorian death masks, and the walls are covered with striking portraits of members past.

Most incredibly of all, the Players contains one of New York’s most secret and wondrous places; a perfectly preserved 19th century apartment, frozen in time under lock and key, that had once been the home of the club’s founder, Edwin Booth, the most famous American actor of his day.

MessyNessyChic was lucky enough to be invited inside this most elegant of town houses, to explore and enjoy the hospitality and bonhomie of one of Manhattan’s most delightful hidden gems.

We will be stepping back in time, to the gas-lamp lit era of the Gilded Age of New York City, and following in the footsteps of the greatest actor who graced its stages.

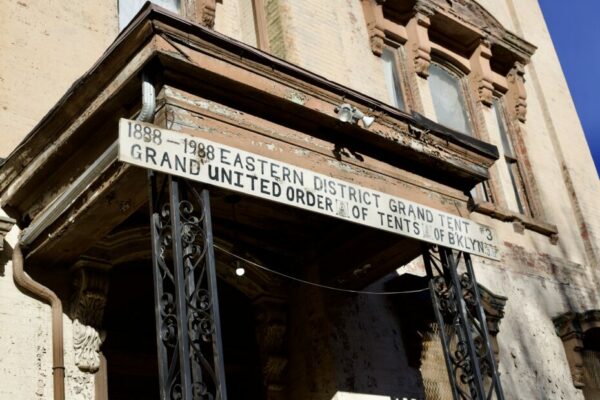

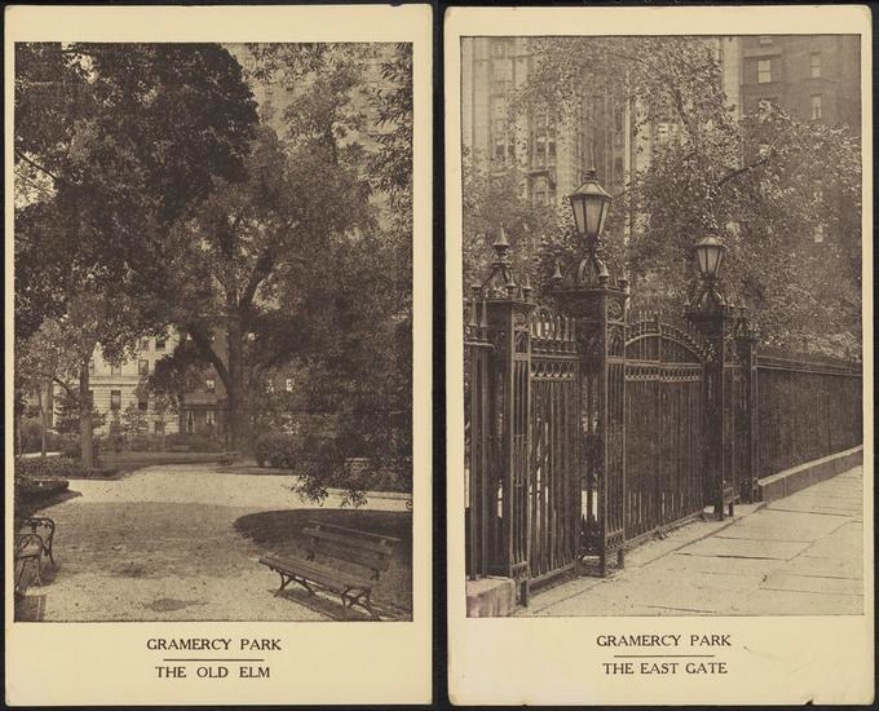

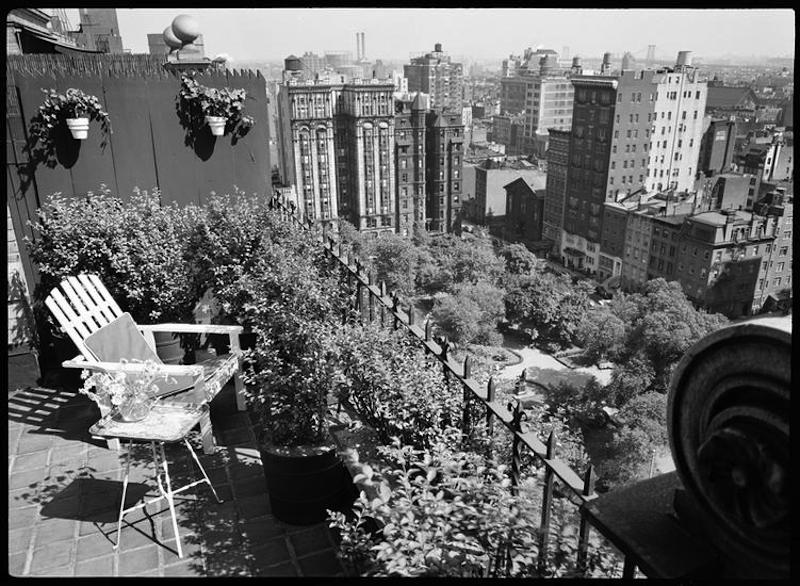

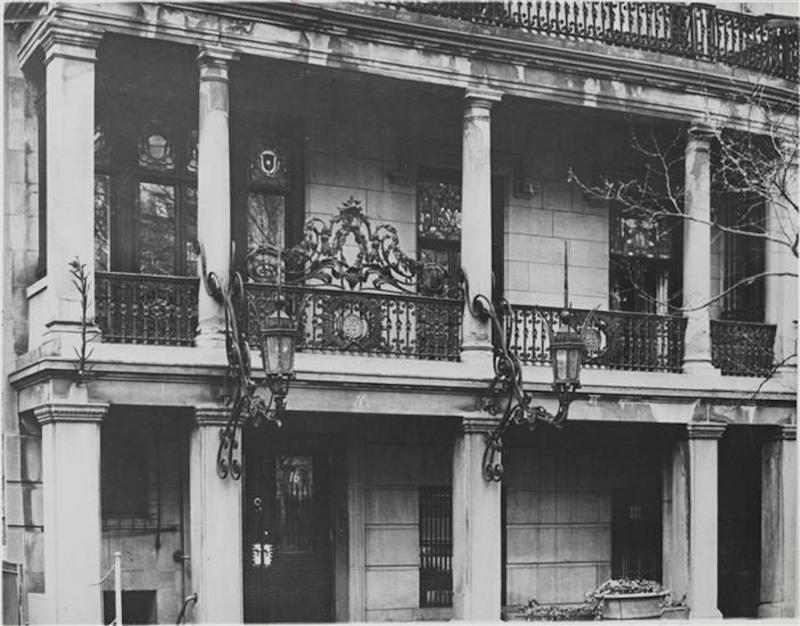

We are beginning our descent into 19th century New York high society appropriately enough, in one of its most prestigious spaces, Gramercy Park. Bounded by 23rd to 18th streets running north to south, and by Third Avenue to Park Avenue South, east to west, Gramercy Park is the only privately owned park in the city.

This small park is an elusive, lush oasis in Manhattan, that you can only gain access to with a key. And to have a key, you must live overlooking the park itself.

Gramercy Park

Here can be found some of the oldest luxury apartments in the New York.

To differentiate themselves from other city apartments and tenements, they were advertised as ‘French flats’. Today, they are still decorated with ornate, wrought iron balconies, and the park remains a secret garden, that passersby can catch tantalizing glimpses off, through its surrounding fence. Indeed, Gramercy Park looks much as it did a hundred years ago, so much so, you almost expect to find hansom cabs, or a shining black caleche pulling up at the curb.

The Players © mcny.org

The Players can be found at number 16, on the south side of the park. It was here in 1888, that stage actor Edwin Booth purchased a beautiful town house. Booth had his home swiftly remodelled however, as an exquisite, Italian palace from the Renaissance era. With an immense, wrought iron balcony overlooking the park, entrance is gained through heavy, wooden doors, as imposing as they are ornately carved. Still today, you will walk past two of the few, still working gas lamps in the city.

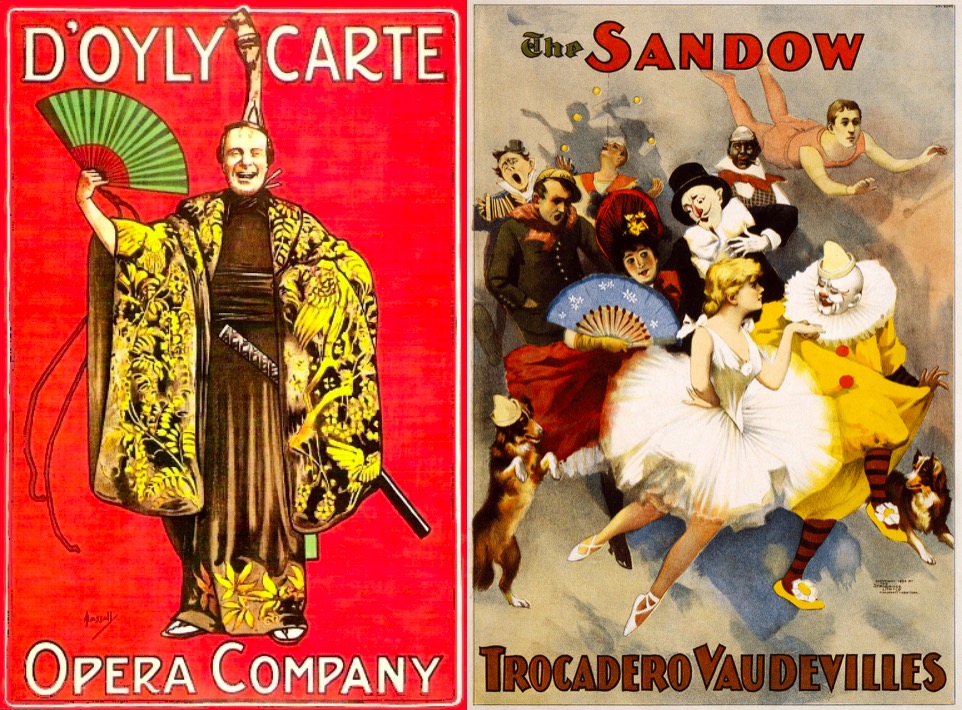

The other, well heeled residents of Gramercy Park were less than thrilled at the prospect of a club for actors being on their doorsteps. For the acting profession in the 1800s was not quite the same as it is today; actors were often seen as louche second class citizens, often not well paid, and involved in a somewhat bawdy profession of dubious morals.

But this was one of Booth’s main aims : to raise the profile and respectability of the acting profession. For number 16, Gramercy Park South was not just to be his home, but a sparkling new, private club for actors set right in one of Manhattan’s most prestigious addresses.

The Players wasn’t created to be a seedy, drinking den for actors; from the beginning, Booth opened membership to all those in society who loved the arts. It was to be a lavish but comfortable clubhouse where actors might mingle with elite Victorian society. It was to be a certain club as Booth put it, “for the promotion of social intercourse between the representative members of the dramatic profession and the kindred spirits of literature, painting, sculpture and music, and the patrons of the arts.’ Founder members included such high calibre names as Mark Twain to General Sherman.

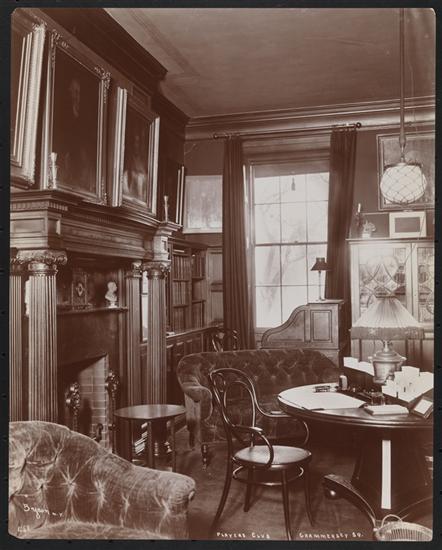

The Players © Luke J Spencer

Walking into the Players today, you are struck by not just it’s Victorian drawing room elegance, but the feeling that you have stepped back in time to the golden era of the stage. Everywhere you look are vibrant portraits of members that cover almost every wall. Some are instantly recognizable, for the greatest names of old Hollywood came here; amongst them James Stewart, Katharine Hepburn, Bogart and Bacall. They look out next to familiar names from entertainment today, such as Jimmy Fallon.

The Players © Luke J Spencer

But many of the portraits are from stage actors long since forgotten. Often painted in character, you can see looking down at you, a sinister Cardinal Richelieu, or a cloaked, haunting Hamlet. It is these mysterious and enigmatic portraits from the past, that give the Players its particular haunting atmosphere.

The Players © Luke J Spencer

The Players © Luke J Spencer

Display cases are filled with faded, gilded costumes once worn in performances over a century ago; everything imaginable, from Richard III’s golden robes, to wicked looking daggers used to thrill audiences in Macbeth, to yellowed playbills from theatres long since torn down.

The other thing which strikes you walking around the Players, apart from enjoying a cocktail in much the same spot as Rosalind Russell did, is the bubbling atmosphere. Many of the old Victorian private member’s clubs face uncertain futures. It used to be the social norm for a gentleman to belong to one, tied closely to his school, profession, or branch of the military. But so many are sadly in danger of dying out, memberships among the younger generation, proving hard to come by.

The Players © Luke J Spencer

But the Players is a thriving club. Packed with members of all ages, all devoted to the arts, everywhere there is the hum of conversation and the clink of cocktail glasses, in an atmosphere most likely identical to when Edwin Booth first opened the club.

If Edwin Booth had set out to create a club where actors could mingle with high society, he had succeeded. And perhaps in the Players, Booth was able to restore some the damage done to his prestigious family name, by one of the most infamous events in American history; the assassination of President Lincoln by his younger brother.

Edwin Booth might not be a household name today, but during the 19th century he was the most famous actor in America. He was known primarily for his poignant and melodramatic performances of Shakespeare’s tragedies. Whilst other actors of the day favoured a loud, bombastic stage presence, Booth was quiet and subdued. He sold out theatres everywhere he went, on one famous occasion performing a record ‘hundred nights of Hamlet’ at the Winter Garden. He opened his own luxurious theatre on Sixth Avenue, and such was his wealth, he was able to have the Players remodeled by New York’s most eminent architect, Stanford White.

But for all his fame, Edwin Booth was to be forever cruelly overshadowed by his younger brother, John Wilkes Booth, the man who murdered Abraham Lincoln. Edwin Booth, the star of the American stage, suddenly shared his name with the most infamous, and hated man in the country.

After the death of Lincoln, Booth retired from the stage virtually overnight. By opening the venerable and popular Players two decades later, Booth was able to give something splendid back to a society so grievously wounded by his brother’s actions. For the Players was not simply a clubhouse; Booth also started to collect what would become an important archive of theatrical artifacts.

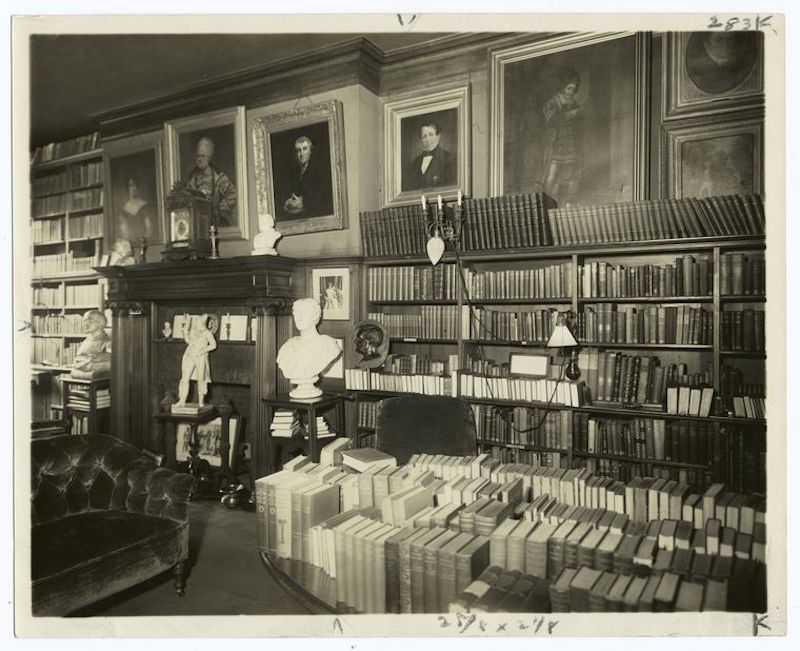

The Players Library © NYPL

The exquisite, wood paneled library on the first floor, is home to one of the largest collection of plays, prompt books and playbills in America. Outside the library is another door, with a knocker of a miniature Shakespeare and a discreet plaque which tells that in this modest room in 1913, the Actors Equity Association was created. Unions being frowned upon at this time, the plaque notes how they met ‘without permission’.

The Players © Luke J Spencer

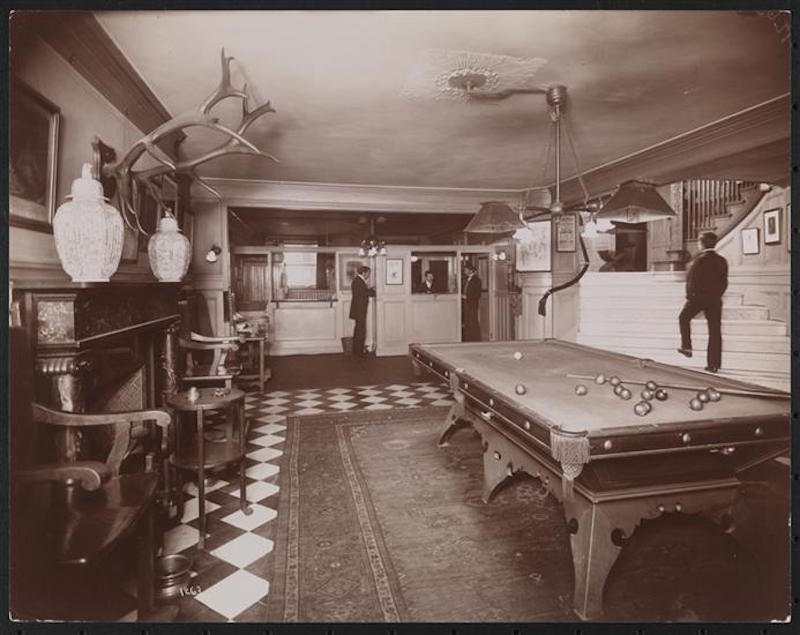

Along the sumptuously red carpeted corridor is the card room, complete with member Mark Twain’s card table. Twain’s billiard cue can be found mounted above the mantlepiece in the grill and billiard room. You pass by the original elevator, called the ‘Sarah Bernhardt Room’, after the iconic actress visited the club once, and legend has it, she was stuck in the elevator for over an hour, and left in a huff, swearing never to return again. She can still be seen though, in a full length photograph which adorns the wall of the tiny elevator where she once spent an uncomfortable evening. The Players is steeped in theatre history.

The Players © Luke J Spencer

But it is a floor up that contains one of the most thrilling secrets to be found in New York. For in the upper floors of the Players is the old apartment of Edwin Booth. He spent the last years of his life in these modest but comfortable rooms, nestled amongst the treetops of Gramercy Park. The Booth Room is kept under lock and key, even the members can’t simply walk in there.

If entering the Players seems like stepping back in time, exploring the secret Booth room, very much feels like it. The first thing you notice is the air; this room has been more or less sealed, apart from the occasional visitors, ever since the great actor died here, in the canopy bed in the corner in June, 1893. The air isn’t musty the way old houses are, it is cold with a strong trace of tobacco, as if Booth had just finished smoking one of his many, beloved pipes that are dotted around the room.

There’s a sitting room, and a bedroom, decorated with faded Victorian swirling wallpaper, and artifacts from the great tragedian’s life. On the table, a book of Tennyson’s poems lies open on the page Booth was reading the night he died. Under the antique, gasoline lamps, you can see a skull on the mantlepiece. The hidden’s rooms haunting atmosphere is heightened when you realize its an actual human one. Clubhouse legend has it that a horse thief, convicted and sentence to be hung, bequeathed his skull to Booth, whom he admired, to be used in his performances of Hamlet.

The Players © Luke J Spencer

The two rooms have been perfectly preserved ever since Booth died. The great actor’s old, brass bed is covered with a faded, silk coverlet, that is made up of small, once colourful squares of material from his old costumes. His slippers are still waiting underneath the foot of the bed, and next to it, a small day bed, where his daughter watched him pass away.

Story has it, that after Lincoln’s assassination, Edwin Booth would leave a room if his brother’s name was mentioned. But in the corner of his bedroom, there is still on the wall, a small, faded, framed photograph of his younger brother. There is also a heart breaking letter from Edwin to the people of America, thousands of whom watched him on stage. Written in June, 1865, he wrote, “for the future-alas; I shall struggle on in my retirement bearing a heavy heart, an oppressed memory and a wounded name – dreadful burdens – too my welcome grave.”

The Players © Luke J Spencer

Whilst many private clubs have floundered in recent years, the old clubby world not quite in tune with today’s generation, the Players is thriving. Its many rooms are still used for play readings and rehearsals, members fill the grill room dinners, pipe nights, and lectures. Nichole Donjè, the Communications Chair, explains how, “It’s an exciting time. We have more than doubled our youth membership this year. I believe this means the art of the social club is making its comeback. People, young and old, are looking for a connection: face-to-face relationships. That is the heart of what we have to offer at the Players.”

The Players is the oldest social club in Manhattan that still operates from its original home, and its vibrancy in a large part stems from staying true to Booth’s original aim, the love of the arts. “The Players holds a remarkable collection of artworks representing the history of theatre, much of which is displayed throughout the building. The collection includes works of art from well-known painters such as John Singer Sargent, Norman Rockwell, James Montgomery Flagg and Everett Raymond Kinstler”, explains Michael Gerbino, long time member of the Club, and current Vice President, and Chair of the Branding Committee. “It is a unique place with like-minded, interesting members who come from all the corners of the globe.”

The Players an active, private social club. Membership details can be found at here.

By Luke J Spencer