This story begins with an Italian architect roaming the meadow of an elitist Cuban golf course. “The first thought I had, looking at the site, was that I could walk down across the field, describing an ‘S’, with my arm outstretched like a plane.” It was April 1961, the bay of Pigs incident had just unfolded and the revolution seemed cemented on a successful path. By that time, Cuban literacy rate had already risen from 60% to 96%, made possible by a year-long closure of all universities that saw students sent across the countryside to teach farmers how to read and write. In the meantime, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara were developing a radical school reform. As part of this “cultural revolution”, an exclusive country club in Havana was be transformed to a public space; a major cultural institution filled with hundreds of art students that would gather at a cluster of five art schools. The Italian architect, Vittorio Garatti, was standing there on that golf course, trying to envision his little piece of a revolution.

Castro and Guevara playing golf on the soon to become grounds of the National School of Arts © Alberto Korda

Castro commissioned Cuban architect Ricardo Porro to design the complex but the impossibly short deadline (three months) caused him to seek help from two Italians he had met in Venezuela, Roberto Gottardi and Vittorio Garatti. The architects began working day and night, developing autonomously one or two projects each.

© Vittorio Garatti

Their designs break free from most of the unwritten rules of contemporary architecture, given the unique chance to play with unusual shapes in a context with no existing structures to work around. The approach was revolutionary when compared with the strict “form-follows-function” practice that was mainstream in those years.

John Loomis: Revolution of Forms

The project had very high hopes– a utopian vision of the Revolution with strong ideological connotations that would have welcomed international students from all over the (socialist) world to study in Havana.

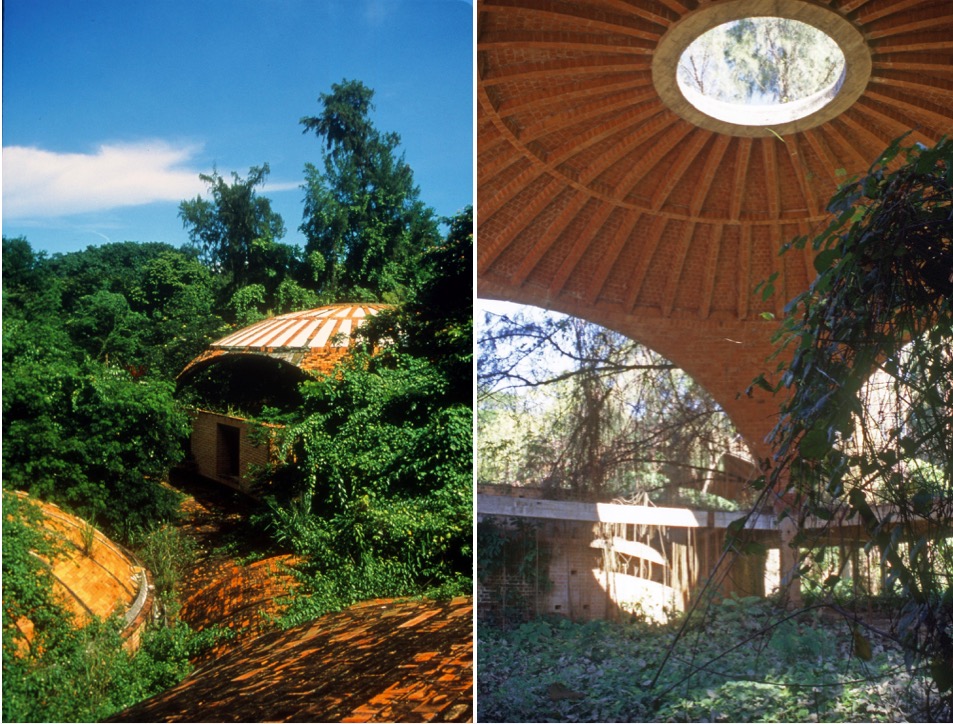

Of the five schools that were constructed: Modern Dance, Plastic Arts, Dramatic Arts, Music, and Ballet– Garatti’s Ballet School certainly stood out. A surprising labyrinth of daring brick vaults meant to express the hopes for a new society.

School of Ballet © Adrián Mallol i Moretti

The vaults are built in a Catalan traditional technique, and are among the biggest of their kind. The Catalan technique, although rather well known in Latin America, wasn’t a common feature in Cuban architecture and construction workers had to be trained for the purpose of the project. In response to the US embargo on Cuba, they used locally-produced bricks and terracotta.

School of Modern Dance © Adrián Mallol i Moretti

The library and the practice rooms found their place under breath-taking umbrellas that hover, like flying saucers, on the gentle topography of western Havana. A sinuous system of vaulted corridors links together the main spaces, with light coming from between the brick sails.

School of Plastic Arts © John Stubbs/World Monuments Fund

In Garatti’s words, the “spatial anguish” that one feels inside the school was a sensory representation of contemporary Cuban society, an anti-capitalist statement. The country was taking its first step into a future full of hope and uncertainty. The architectural response to such an historical moment had to be bold and cutting-edge.

School of Plastic Arts © Adrián Mallol i Moretti

Unfortunately, the “romantic period” of the Cuban revolution wouldn’t last. In 1964, the economic difficulties following the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 led to a sudden change of heart. Castro called for a more sober, less extravagant practice of architecture that didn’t require an unnecessary use of resources. Cuba also had a new alley, the USSR, which encouraged a new “anonymous”, “practical and functional” architecture based on modular elements.

© Adrián Mallol i Moretti

This stood in stark contrast to the exuberant shapes of Garatti’s school that were now seen as too “ego-driven” and “bourgeois” to be compatible with the principles of the revolution. The project conceived to portray the optimism of an entire generation was suddenly off the agenda. All three architects hired by Castro himself, were branded as cultural elitists and eventually compelled to leave Cuba.

School of ballet © John Stubbs/World Monuments Fund

Today, the school is not easily accessible and waits for a much-needed restoration. For many years, The beautifully designed timber frames were dismantled and the former golf course is slowly turning into a forest. Nonetheless, the terra cotta vaults still stand as the uncanny relics of a dream that never came true. In a summer a tropical shower, you can take shelter under Garatti’s joyful trenches: the powerful design is still enchanting and raise questions that the 20th century couldn’t answer.

© Adrián Mallol i Moretti

In the 1980s, the unfortunate art schools were given protection under the architectural patrimony of Havana, and in the 1990s, the architects were invited back to Cuba as their contributions were finally recognised and their unfinished schools declared the most important architectural works of the Cuban Revolution.

© Adrián Mallol i Moretti

They are not only fascinating pieces of derelict architecture to study, but also serve as a milestone of a very intense period in the history of the island, when hopes for a brand new society first met the economic consequences of the embargo.

After a historical meeting with Porro, Garatti and Cuba’s Minister of Culture, planning began for restoration. Renowned architects such as Norman Foster were invited to help redesign the Ballet School and Porro’s School of Plastic Arts and School of Modern Dance began to see new life in 2008. But with the global financial crisis, the project has once again been brought to a halt. Even as these derelict masterpieces are currently being considered for inclusion on the World Heritage list of sites which have “outstanding universal value” to the world, it is still difficult to foresee a future for them.

A documentary Unfinished Spaces tells the story of the schools and features interviews with the architects…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=121&v=eAKrsBwUNxc

The beautiful ruins seem to belong to a different era. Still the tropical elements beat the time.

By Andrea Valentini