Parisians often talk about the great travesty that was the loss of Les Halles, a legendary food market in the heart of Paris, fondly referred to as “the belly of Paris”, a seemingly indestructible monument to the great tradition of French markets. It was demolished in 1971 and the hub of all food distribution in the city was moved to a more practical site in the suburbs, next to an airport, much to the chagrin of the Parisian working class. But what about the great loss of Paris’ wine village? Once the largest wine market in the world, a forty-two hectare time capsule of 18th & 19th century Parisian village life, entirely wiped out in the 1980s– why don’t we talk about that?

A five-minute drive past the Notre Dame along the Seine on my old Peugeot mobylette, I arrive at Bercy, the 12th arrondissement neighbourhood that was once the thriving centre of the Paris wine trade and a unique place of culture and festivity. Until 1860, Bercy wasn’t yet part of the city of Paris, which meant wine was duty-free– which meant it was pretty much ‘Happy Hour’ here all day long.

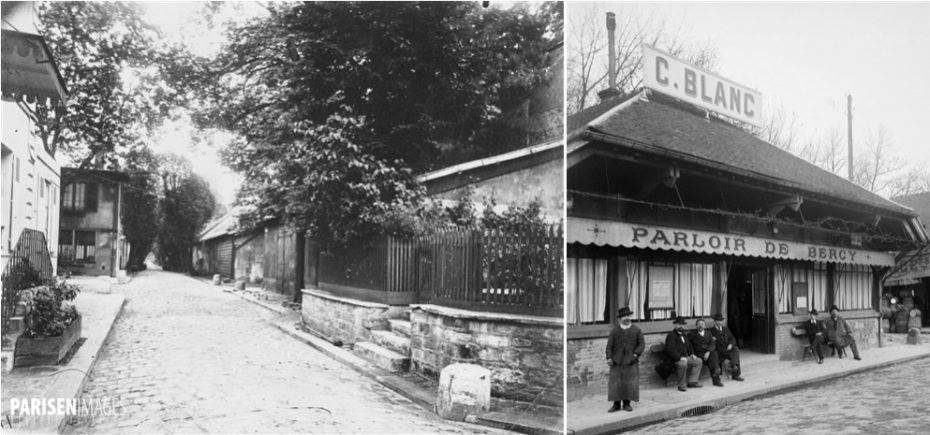

It was only natural that merry Bercy was home to some of the best taverns, cabarets and dancing venues (guinguettes), side by side with the wine merchants and their storehouses. Bercy was essentially the largest wine cellar in the world, where the precious grape juice was both sold and enjoyed.

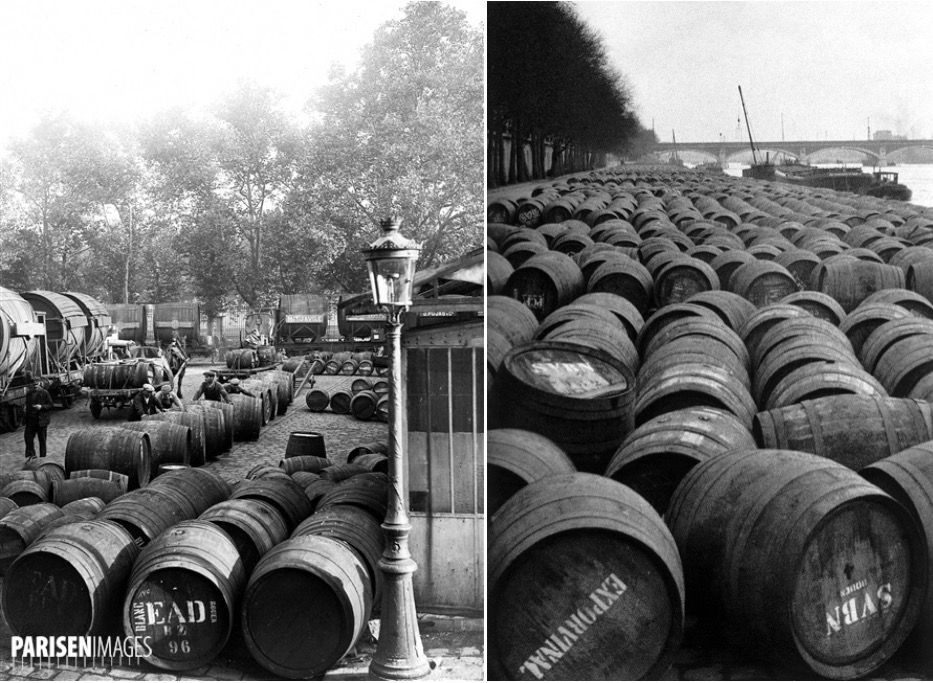

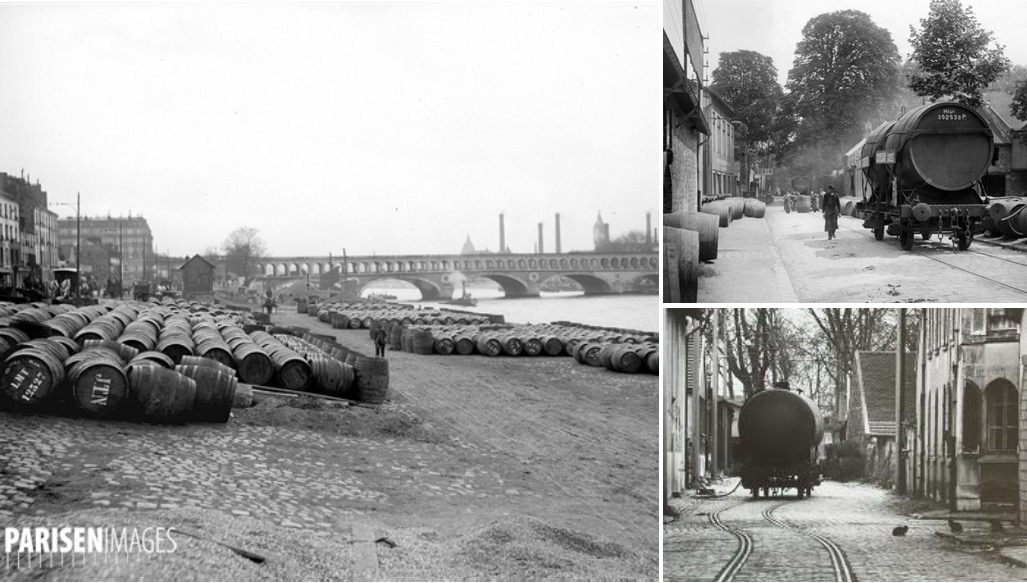

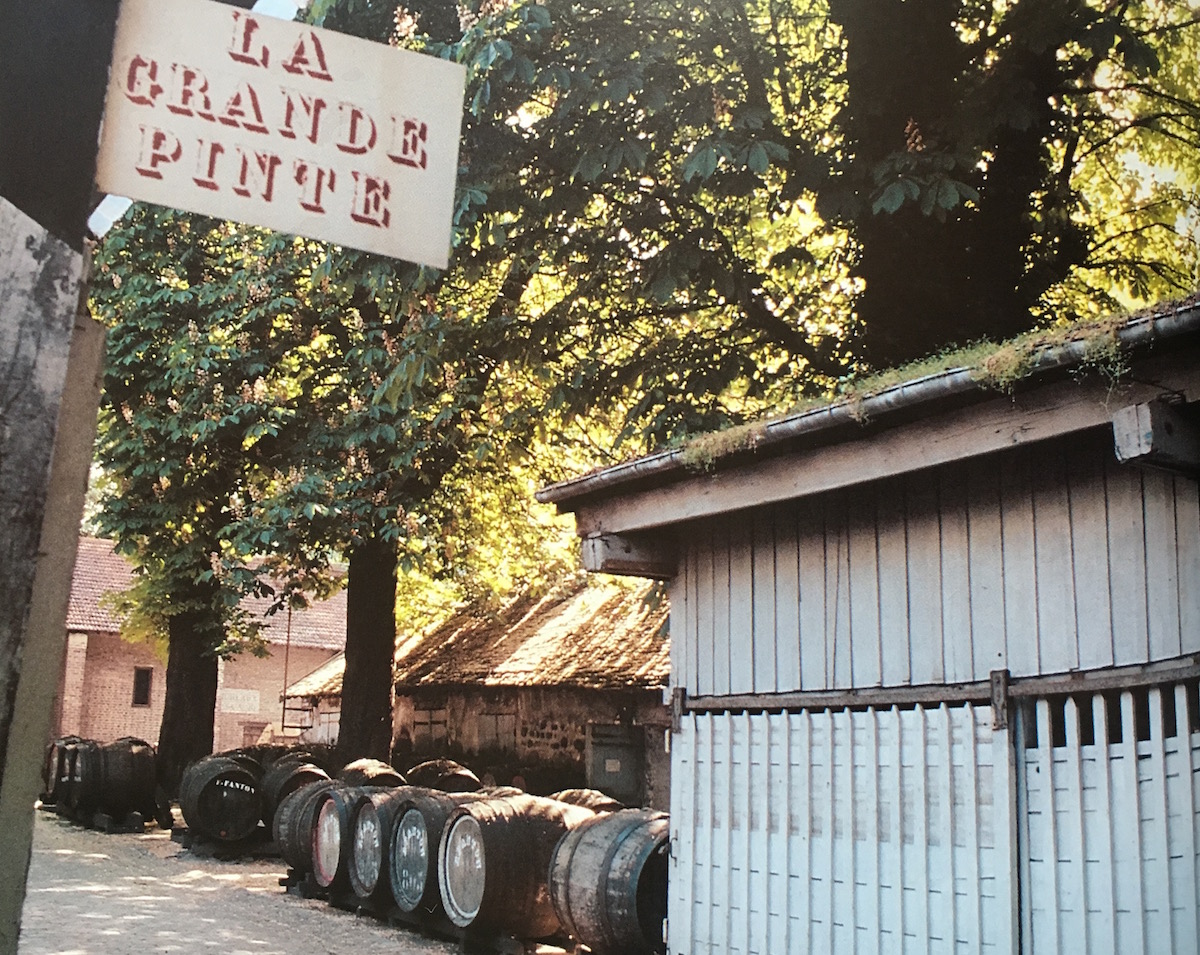

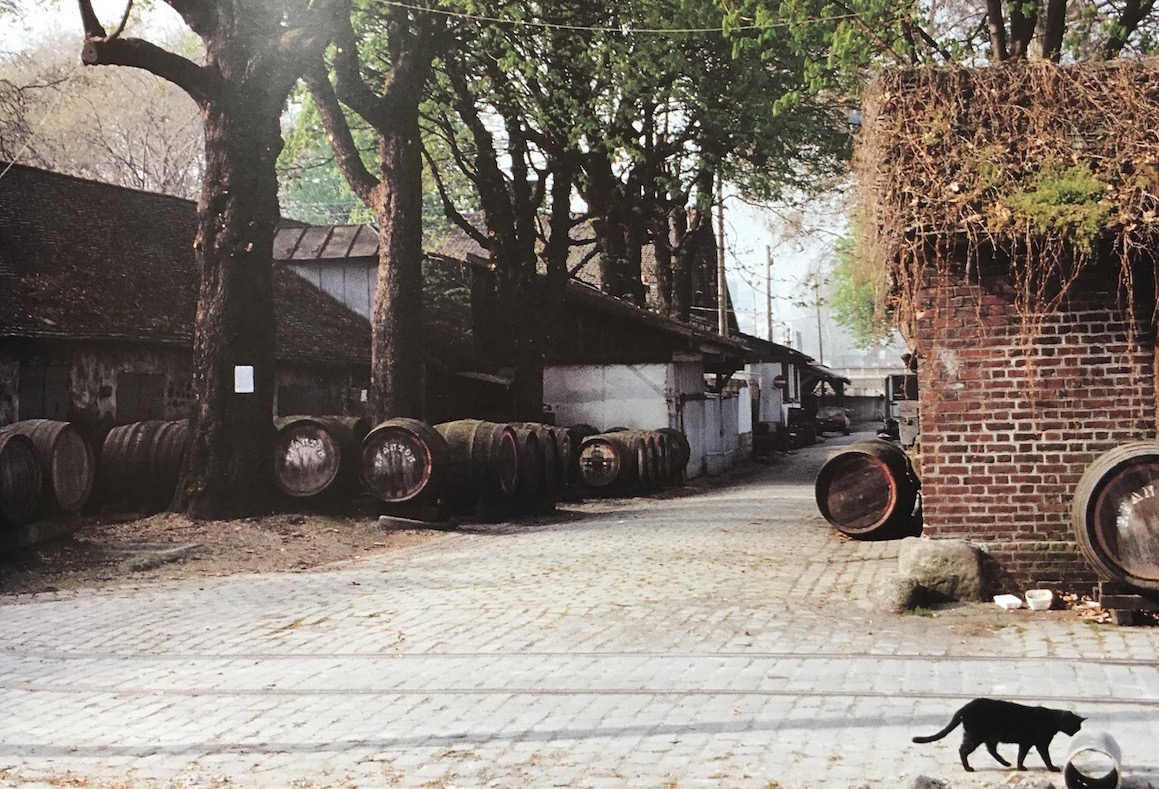

Wine barrels arrived in Paris by boat via the Seine and were unloaded at the banks of Bercy onto train tracks that brought them into the village for bottling, storage and trade.

The biggest wine merchants in Europe set up shop here, making a fortune at a time when wine consumption in Paris had surpassed 3 million hectolitres per year by the mid 19th century.

However, with the control over the bottling process, wine merchants also had the opportunity to trade a product of dubious quality. It wasn’t uncommon to sell bottles containing wine partly from Burgundy, a touch of a Côtes du Rhône and a little top up of vino from Algeria.

In the 1960s, French consumers became more demanding of their wine and favoured the practice of bottling at the wineries, under the eye of the producers. And it was at this time that the largest wine market in the world began to see its decline. By the late 1970s, Bercy was somewhat of a ghost village.

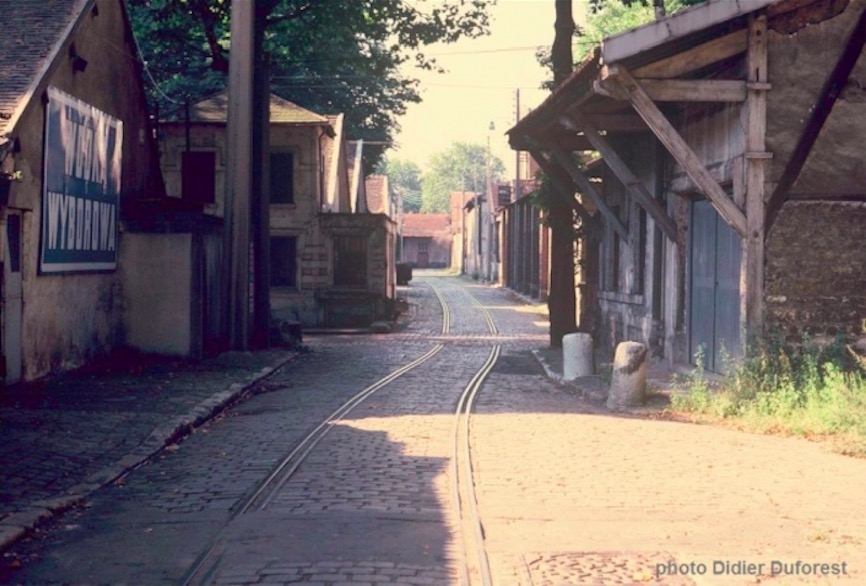

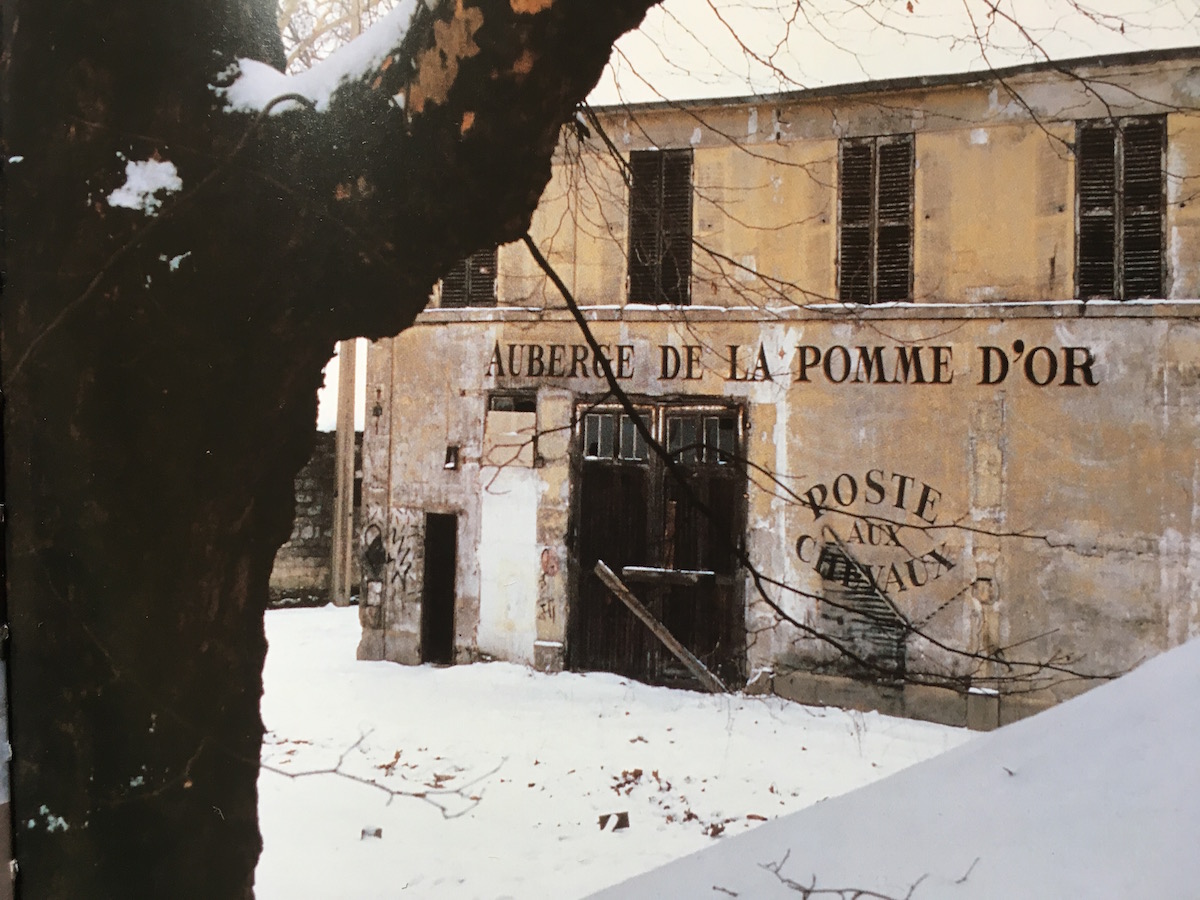

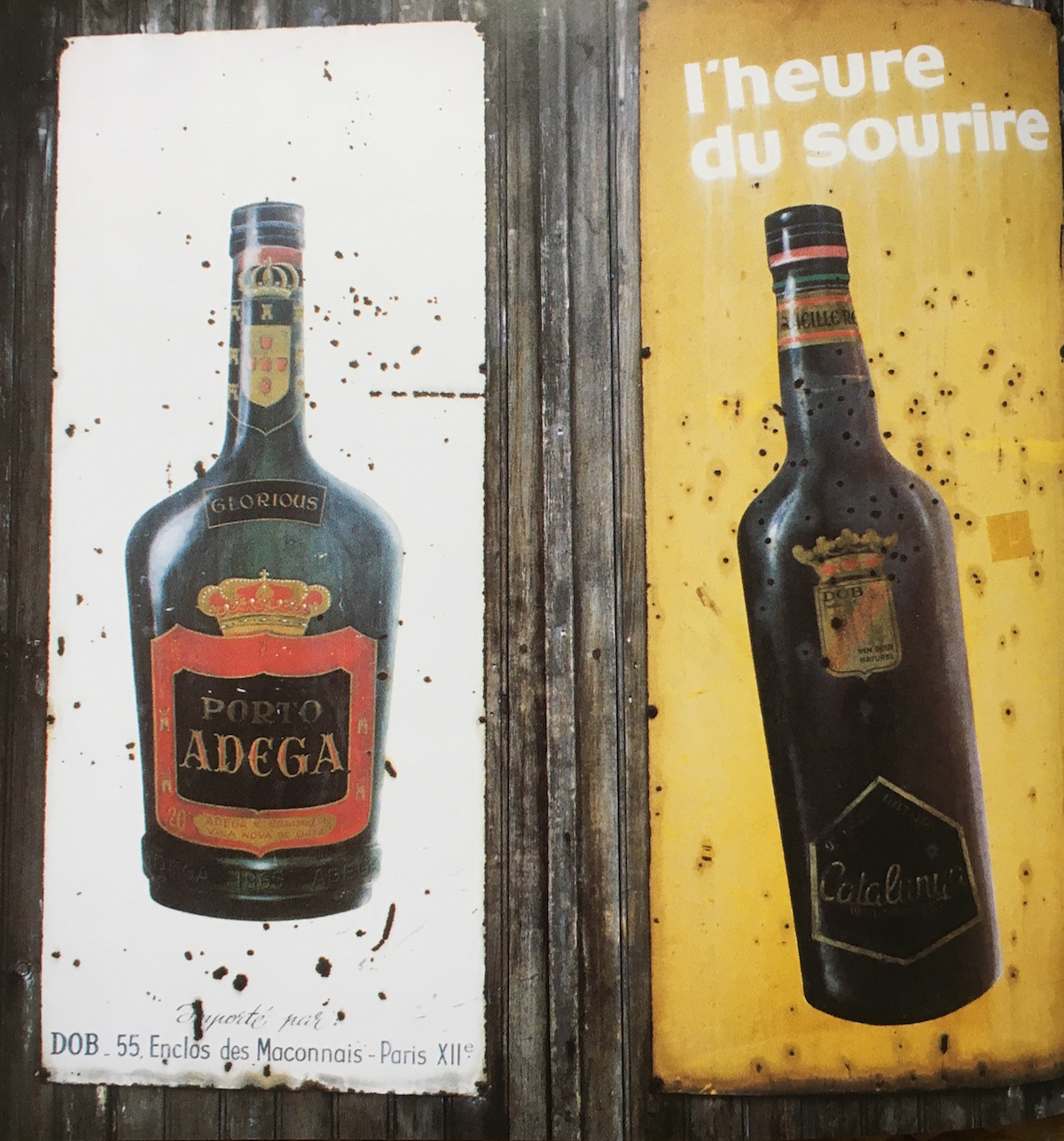

It was no longer the vibrant and thriving quartier it once was, but it was a unique place out of time, characterised by buildings with faded lettering, century-old trees, cobblestone streets with embedded railway tracks and abandoned wine barrels lounged on by the sleepy village cats. It was a mythical place far from the modern gentrification that is forever threatening to rob Paris of its old world charm and nostalgia.

I recently found some photographs taken of old Bercy in its last moments, from a wonderful book by Yvan Tessier…

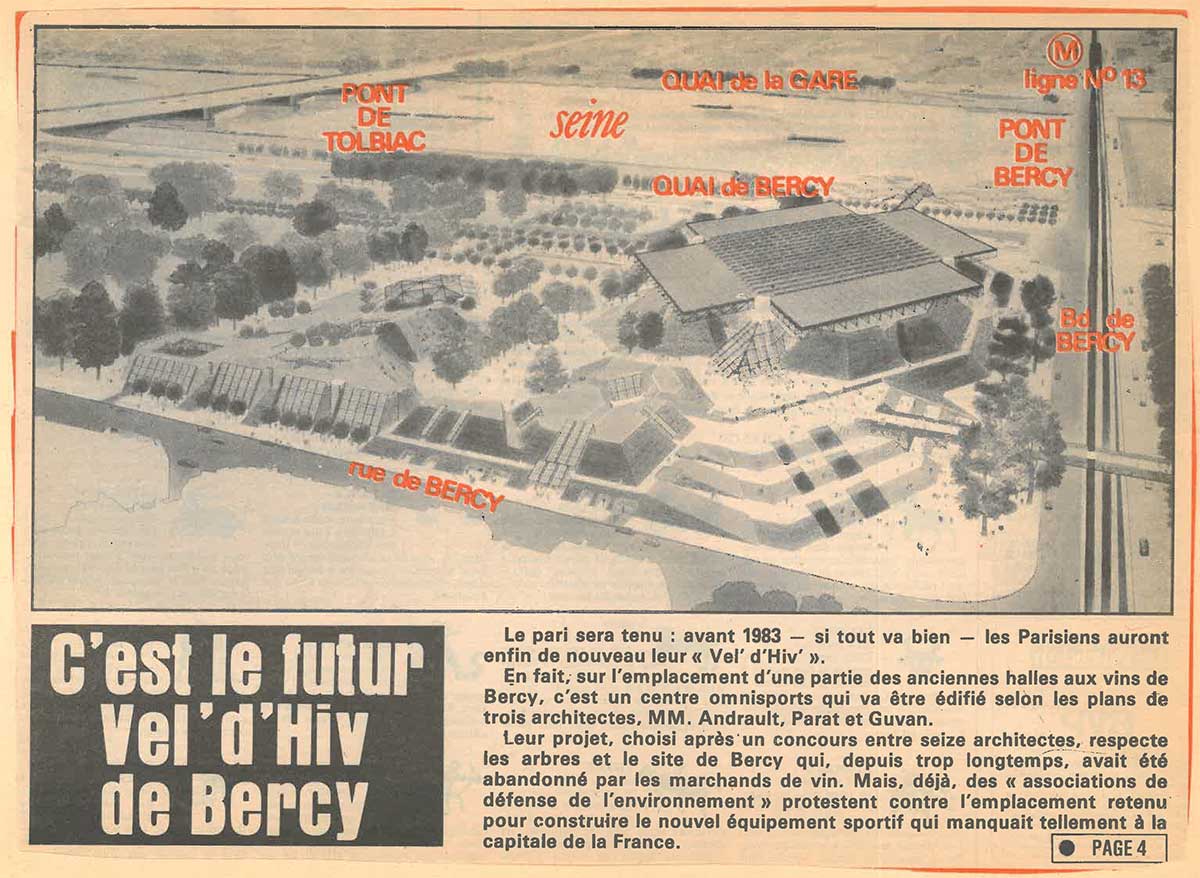

But then the inevitable happened. Financial opportunity presented itself and the neglected village of Bercy was earmarked for redevelopment. Local associations tried to protest against the death sentence for one of Paris’ most historic districts, but the developers had a better argument. With plans to replace the old village with a giant stadium that would welcome and entertain thousands, build a park surrounded by offices, commercial centres and modern apartment blocks that would house hundreds more, the redevelopment of Bercy was a project that on the contrary, would bring life back to the area.

Within a few years, under President Francois Mitterand’s reign, developers had almost entirely erased the old Bercy village, a piece of Paris gone forever. On some of the oldest vestiges of human occupation in Paris dating from the late Neolithic period, a soulless modern commercial development sprang up in its place.

As I attach my bike to a railing and look around at the cold glass buildings, I realise I’ve arrived at Bercy about 25 years too late. But I haven’t travelled to this part of Paris for nothing. For in the wake of the village’s destruction, there were traces of it mercifully left behind and I’ve come in search of them.

Some of the remains have been preserved better than others…

The most obvious nod to Bercy’s history is the Passage Saint-Emillion (named after the wine of course), a row of renovated 19th-century wine storehouses and pavilions that escaped the wrecking ball and were converted into shops and restaurants.

The cobblestoned street with embedded railway tracks stayed too, and in theory, this could have been a very charming revival of “vieux Bercy”. But developers clearly missed the point of trying to preserve a piece of the village’s history and spirit when they allowed in restaurant and retail chains such as Five Guys, Sephora and Fnac.

Moving on, I’m headed around the corner to find a second set of storehouses spared from the destruction of the 1980s, where the pavilions are privately preserved by a very special museum…

I have an appointment at the Musée des Arts Forains, the result of one man’s fascination with rare funfair antiques, games, theatrical props and lost treasures dating back to the 1800s.

The eccentric Parisian collector Jean Paul Favand (who used to hang out with the likes of Dali and Robert Doisneau), created his own wonderland here in 1996 inside Bercy’s last wine storehouses.

While the museum is dedicated to the history of fairground treasures rather than wine, here you can still be transported back in time and find that charming village spirit that Bercy was once famous for.

Before returning to my corner of Paris, I wander inside the park that was built over the rubble of a raised village. At the centre of the park, one of the wine trade’s old buildings has been spared, a romantic house with charming country shutters and a greenhouse attached. This urban cottage now serves as the “Maison de Jardinage”, a welcoming public learning centre to encourage urban gardening. Around it, we find the cobblestone paths again with embedded train tracks that now lead nowhere, stopping abruptly and re-appearing again on the other side of a modern fountain.

Finally, I find the last piece of my hunt for the lost Parisian wine village, perhaps the most poetic reminder of its history– one of the city’s eight vineyards. Ironically, this vineyard growing sauvignon and chardonnay grapes and allegedly producing around 350 bottles a year, was only planted in 1996– but I like to think it was once planted by a 19th century wine merchant in his courtyard. Like most things I’m too late for in Bercy, I’ve also missed the grapes this year. They’ve already been picked, perhaps just last week. We are of course in the midst of the Parisian wine harvest, most notably celebrated in Montmartre, where a five-day festival sees the hilltop village brimming with eclectic and traditional events.

As I walk back to my mobylette, looking up at the 90s apartment blocks that aren’t ageing particularly well, I can only wish I’d had the chance to see Bercy as it was, or that someone had managed to convince the city of a different vision for its future– one that included the foundations of its past.

All too often, I find that I face the misfortune of being born too late. I also find that the best way to make up for my misfortune is to drink away my nostalgia with a bottle of red wine– which seems appropriate in this case. Won’t you join me? It is the Parisian wine harvest after all.