This is the forgotten story of a brave (and perhaps slightly mad) scientist and his two men, who made a perilous one way journey to the furthest ends of the earth. And if an expedition to the North Pole in itself wasn’t dangerous enough, they decided they would do it in a hydrogen balloon. Thirty-three years after their vessel lifted off into the howling Arctic winds, the remains of their last camp was discovered, along with five exposed rolls of film documenting their surreal and ill-fated adventure into the unknown.

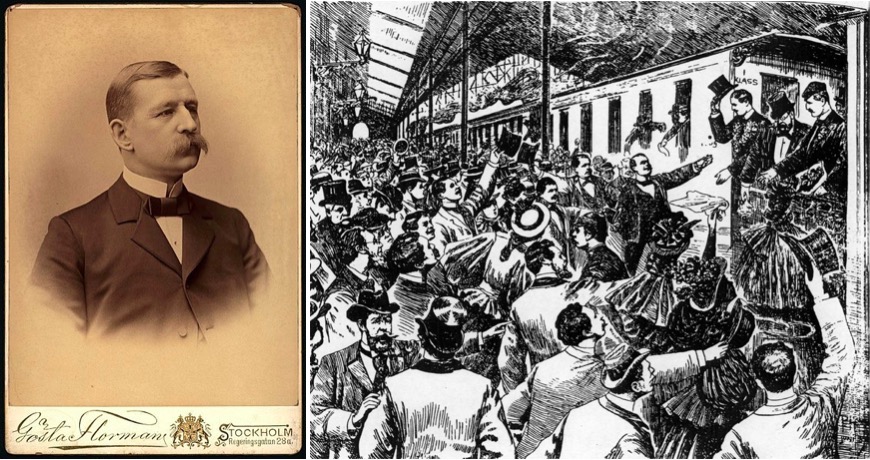

Salomon Andrée was a Swedish balloonist, engineer, physicist, polar explorer– and before all that, he was a janitor. As a young man, he’d just graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering when he travelled to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and found employment as a janitor at the Swedish Pavilion. It was there that he met the American balloonist John Wise, and thus began his lifelong fascination with balloon travel.

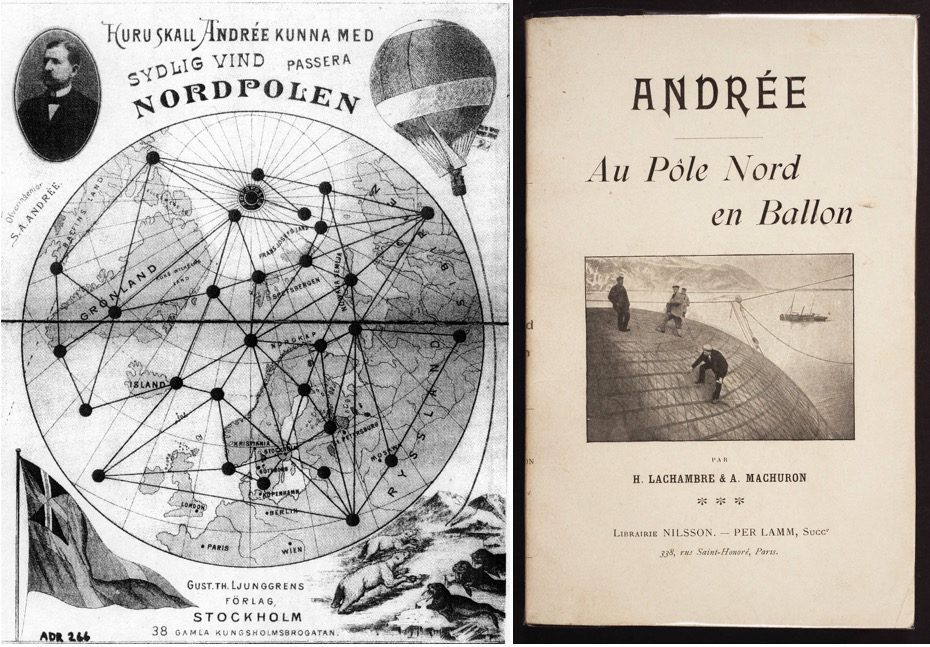

Back in Sweden, by the age of 43, Andrée was a national celebrity; the man at the centre of a daring polar exploration to fly over the North Pole, which was the subject of enormous interest, seen as a brave and patriotic scheme. He had the backing of the Swedish government, the royal family and the founder of the Nobel prize himself, Alfred Nobel. (No pressure).

On July 11, 1897, Andrée and two fellow countrymen set off to launch their hydrogen balloon named the Örnen (the Eagle), which had been manufactured in Paris– a hub for hot air balloon innovation (the first aerostatic flight in history took off in Versailles).

The French manufacturer had ensured the balloon would be able to survive the brutal temperatures of the Arctic and Andrée intended to steer the craft with long ropes that would drag on the ice to provide some control.

A special hangar for inflating the balloon was shipped to the launch point on Danes Island, a Norwegian territory 400 miles north of Scandanavia.

And they were off! But almost immediately, trouble began…

Moments after take-off they lost two of the three steering ropes, which weighed half a ton each, causing the balloon to shoot up to high altitude without the extra weight. At that height, the seams froze and started leaking gas, which is when Andrée, an experienced balloonist, engineer and physicist, should have made the call to land at once and call off the expedition. We can never really know why he didn’t, but with an entire nation back home counting on him to succeed, having made promises and getting this far, perhaps it was his pride that kept his expedition going, despite knowing so early on that the flight had no chance of success.

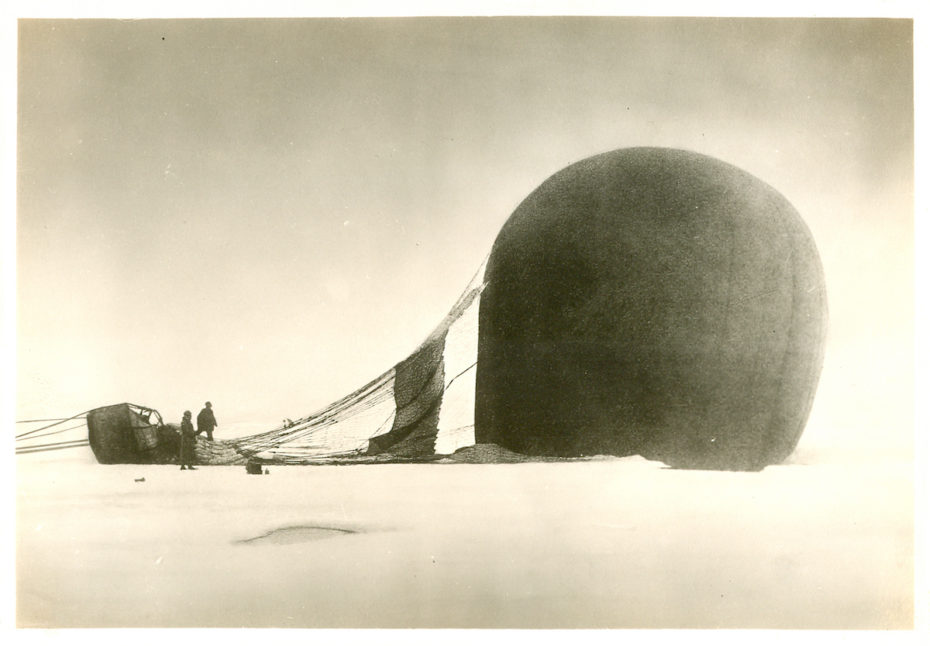

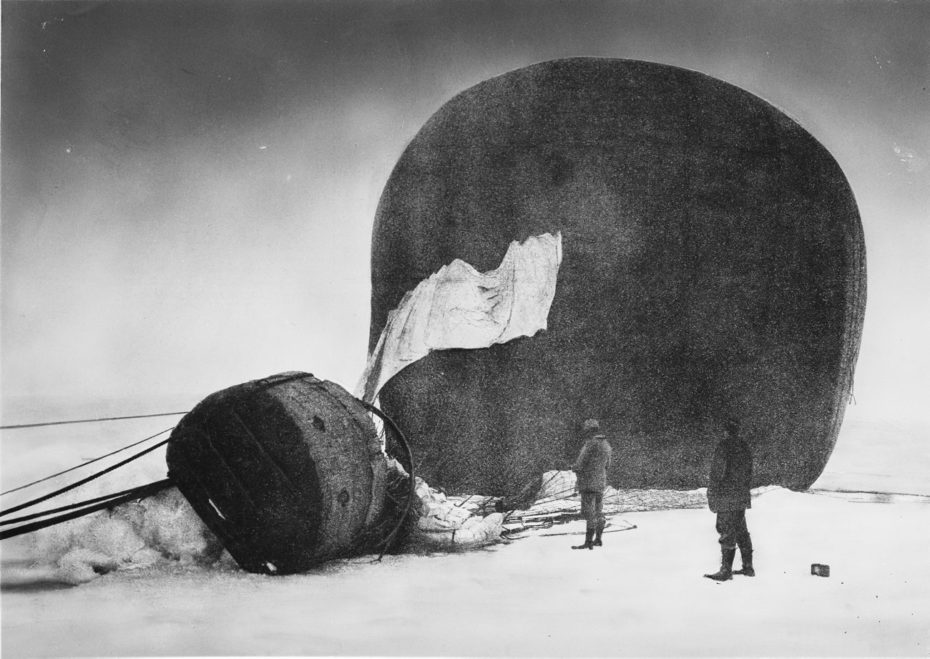

The balloon drifted for three days, during which time the men got no sleep, before crash landing into the arctic ice, never to rise again.

If the wireless radio had been invented, Andrée would have had the chance to alert base, “the Eagle has landed” (long before Neil Armstrong got to say it when he landed a space shuttle on the moon). But calling for back-up was not an option for the three men, who now found themselves stranded in the middle of the North Pole with a very long walk home.

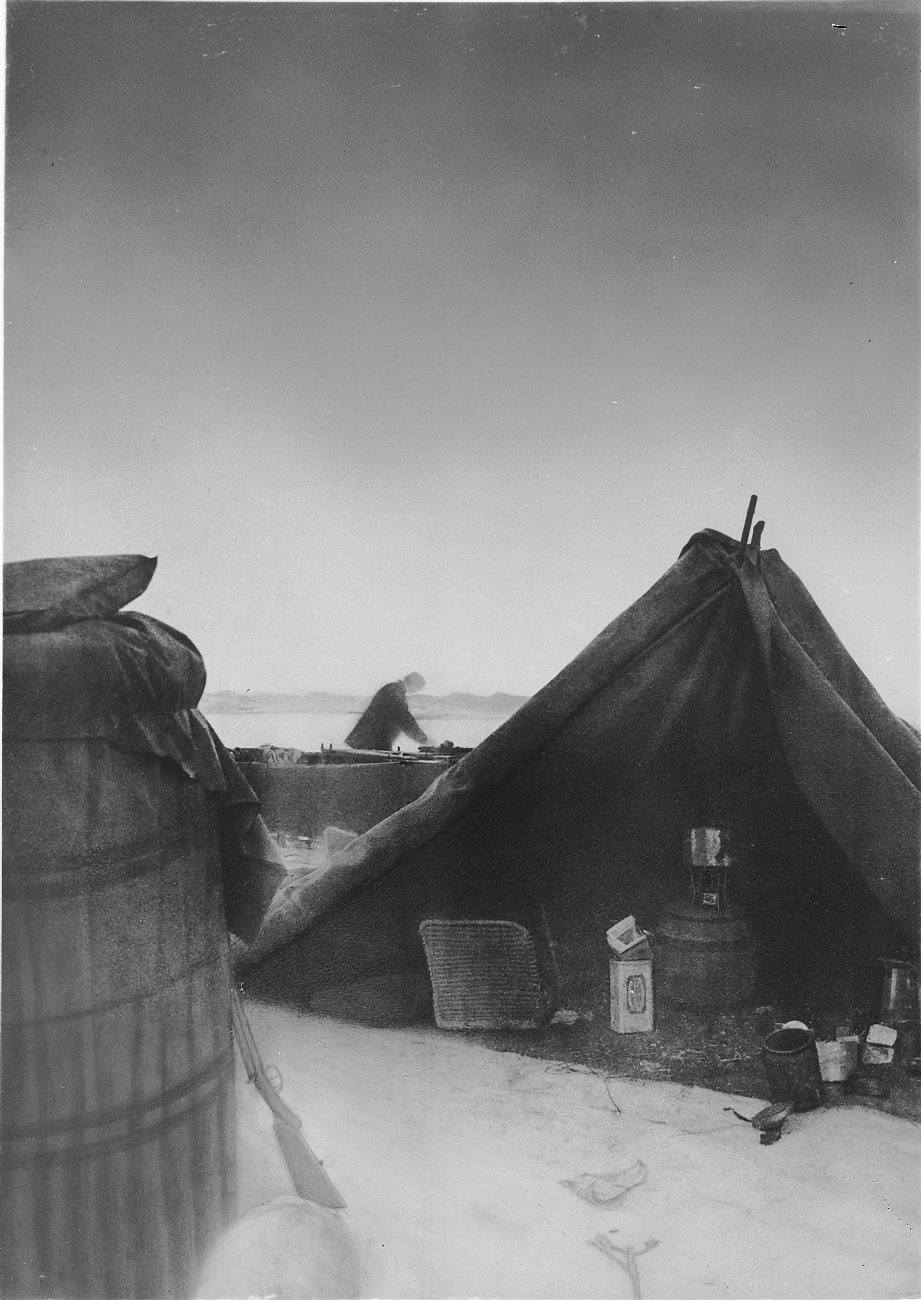

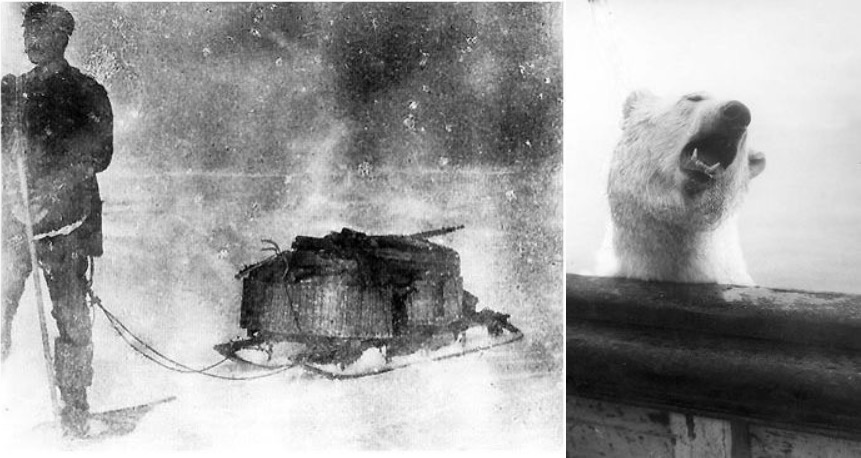

For two months, they survived with the emergency equipment on board, including a tent, sleds, guns, snowshoes, skis and a small boat. Their food supplies were plentiful and they even had crates of champagne, port and beer, donated by sponsors. After the first week, they began ditching the non-essential food supplies and equipment that overloaded their sleds.

They hunted instead, for seals, walruses and polar bears while marching towards a camp where an emergency food depot would be waiting for them.

Throughout their journey, the expedition’s photographer, Neil Strindberg, used his highly specialised cartographic camera, originally intended to map the region from the air, but now served as their visual diary, documenting their daily struggle to reach safety.

All three men also kept journals; Strindberg’s was more personal and Andrée and Frænkel’s were more meticulous in recording their geographical movements, which has helped us track the party’s movements leading up to their deaths (all three diaries were recovered from the ice in 1930).

Despite their lack of experience as explorers by foot, they managed to get pretty far. You can see how far they travelled after the crash on the above map (the dotted line shows their journey south on foot).

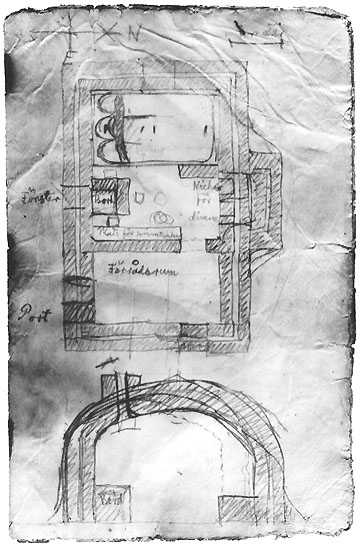

At one point, they even hurriedly built a winter “home” against the increasing cold. Pictured above is Strindberg’s plan for their winter home on the ice floe, used only for a few days before the ice broke up under it. It contained, shown from top to bottom, a bedroom with their triple sleeping bag, a room with a table, and a storeroom.

They never made it to any of the food depots, but reached another small island called Kvitøya. It was concluded from the last pages of Andrée’s diary that within a few days, one of the men died and was buried, and shortly after, Andrée and his last comrade, froze to death in their tents. Morale had remained high to the very end. “With such comrades,” wrote Andrée in their last days, “one should be able to manage under, I may say, any circumstances.”

No one back home had any idea what had happened to the explorers– only that the expedition had been lost. The story became an urban legend, shrouded in mystery. False and disrespectful speculation in the media accused indigenous peoples of the Arctic of being savages, guilty of killing Andrée and his men.

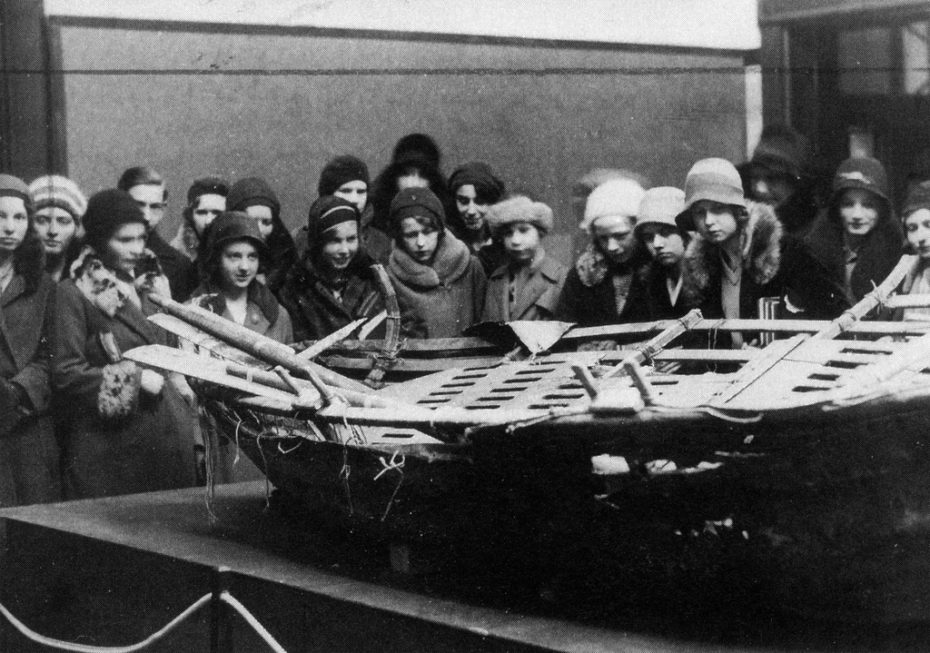

It wasn’t until thirty years later that two Norwegian ships studying glaciers found the remains of the Andrée expedition. Their bodies were sent back to Sweden for a ceremonial burial and their belongings from the expedition found homes in museums and permanent exhibitions.

The photographs from the recovered rolls of film can now be seen in the Nordic Museum in Stockholm.

Salamon Andrée was a man who preferred to face death than to face failure, and his foolhardy polar expedition has been overshadowed by history’s more successful adventures. But Andrée’s hot air balloon journey to the North Pole is an impossible story, one that you wouldn’t believe outside of a Jules Verne novel. So here’s to our mad scientist du jour, Salamon Andrée, who dreamed of the impossible and kept exploring to the very end.