Forget the flappers. It’s time to talk about the “vampires” of yesteryear and their fiery queen of the screen and stage, Valeska Suratt. The Vamps or “vampires” were the female actors that paved the way for the flapper in the 1910s-20s and, in many ways, they were an extension of something exciting brewing in America.

The battle for Women’s Rights was gaining momentum. One by one, states began granting women suffrage. In 1913, the Women’s Suffrage Parade marched on Washington, D.C. (sound familiar?) in the thousands, and the years following saw the first woman ever to serve in the national legislature. America was starting to see women as a force to be reckoned with – and that’s where the vampires come in.

The entertainment industry was open to testing-out stronger female personas, and they did so on a far-reaching platform. Actor Theda Bara’s 1915 film A Fool There Was introduced viewers to a dominant female character, and a number in the Ziegfeld Follies called “The Vampire” started popularizing a term for a new breed of woman who burned fast and bright in the big city, doing as she pleased, known as a “vamp” or “vampire” (partially thanks to the tousled hair smudged makeup she sported with pride).

But of all the vamps, one stood out above the rest: Valeska Suratt.

Suratt was born in 1882 in Indiana, the daughter of a blacksmith in a family of six, and grew up in the town of Terre Haute. She began working at age eighteen in the millinery department at of store in Indianapolis, and eventually saved up enough money to head to Chicago to have a crack at her lifelong dream: the theatre.

The factual details of her arrival to the stage and screen were often embellished, including the story of a fateful party in 1902 at the Wellington Hotel. The young Suratt was said to have crossed paths with the Grand Duke Boris of Russia, who during lunch with her the following day asked, “What is it that you would rather do than anything else in the world? Is there anything you want very much?” to which Suratt simply said, “the stage.” The Duke wrote her a $10,000 check, and split.

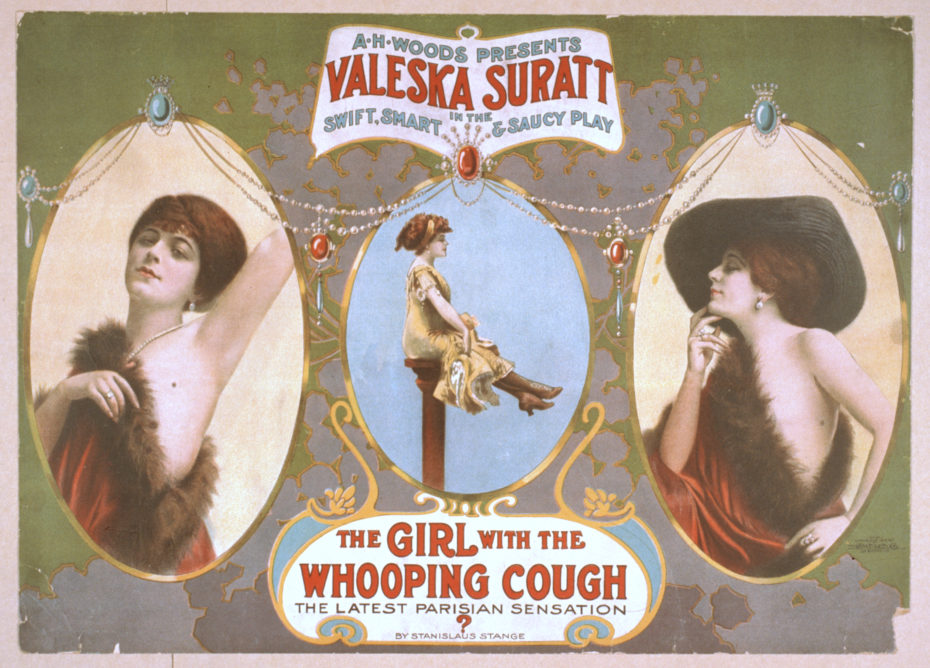

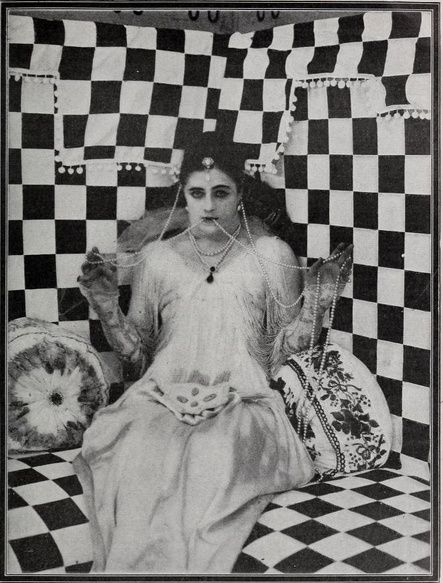

Pamphlet from Suratt’s debut performance.

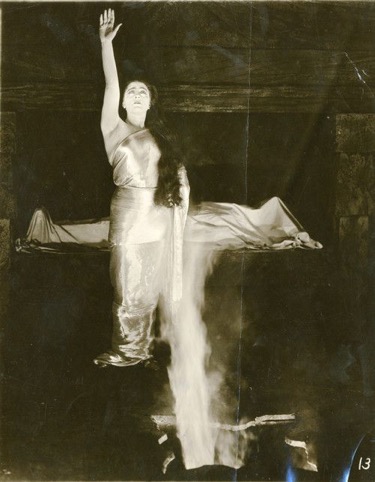

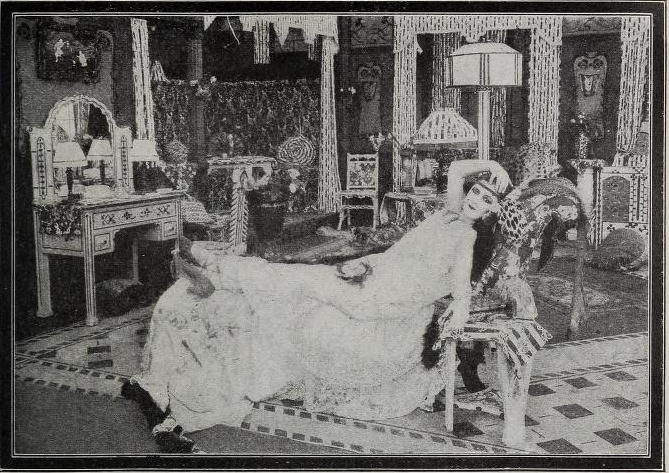

In a scene from the now lost “The Soul of Broadway” (1915).

The Indiana gal began making a name for herself in Vaudeville shows thanks to her acting chops and strong singing voice, and it was there that she met her first husband and show partner, Billy Gould.

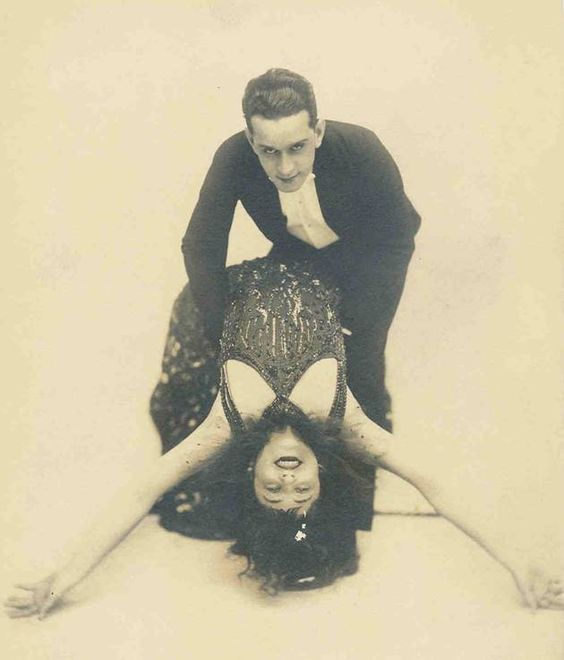

Together, they performed an act that included the infamous “Apache Dance,” a routine that burgeoned in the Paris underground’s (then) suburbs of Belleville and Menilmontant. The dance was extremely charismatic (think Tango, but more jerking and faux-slapping) and completely dependent on the chemistry between its partners. The number proved electric, and by the time Suratt broke into silent film with 1915’s The Soul of Broadway, the public was already hooked.

Suratt does the Apache Dance with husband Billy Gould.

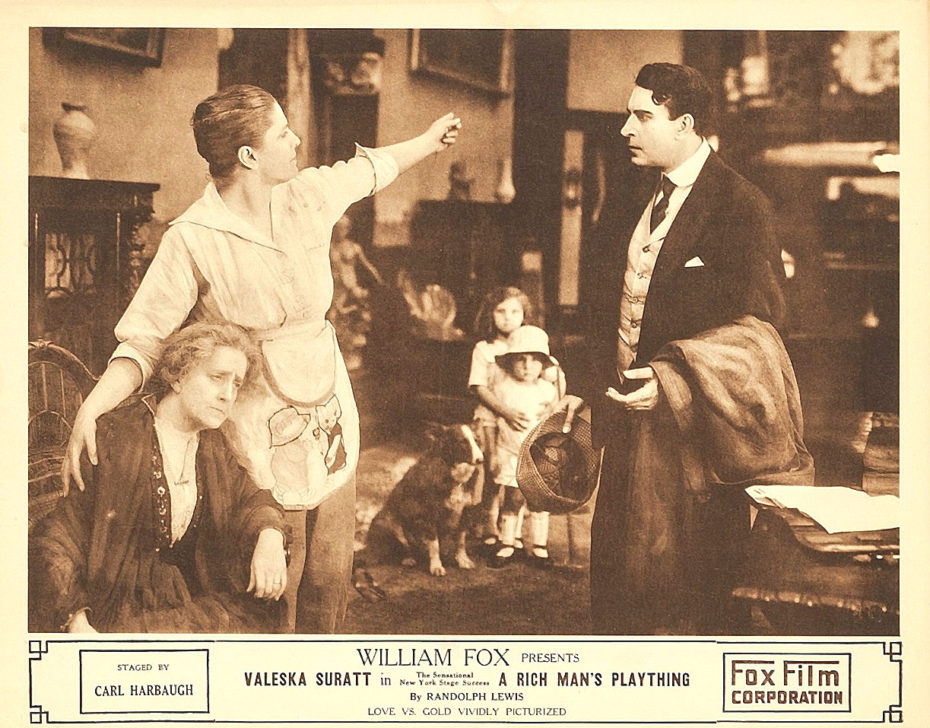

In total, Suratt would appear in a total of eleven films in archetypal vamp roles (i.e. strong-willed, cunning, and sexually autonomous), including Jealousy (1916), the crime drama, The New York Peacock (1917), and Wife Number Two (1917).

Tragically, the films have become lost over the years, their only vestiges the promo-shots and the press reports of her inimitable performances and costumes.

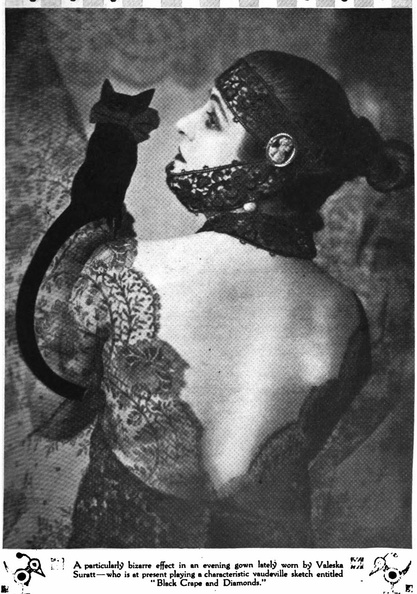

Never one to idle, Suratt began writing beauty advice columns, doing ad spots, and had a remarkable amount of control of the productions she starred in. She also dressed every bit the part of the big-time screen vamp she became, earning the nickname “the Empress of Shopping” due to her eccentric, extravagant taste.

A Chicago reporter once called her dressing room “a shoplifter’s paradise,” and she drove an Oakland Sedan upholstered in blue silk brocade.

In 1917, The Daily Bee reported, “At last the almost impossible has happened…Valeska Suratt appears in a film drama without wearing an array of gowns” in a review of her latest picture.

Clothes aside, Suratt just had that ineffable “it” factor. She also knew how to make headlines such as, ‘I Never Tore or Clawed the Girl’ but Miss Valeska Suratt Admits Pulling the Cord on Miss Horton’s Neck (New York Telegraph, 1907), and was reported to have ripped Jeannette Neal Horton’s dress off her body in complaint that the Gibson Girl had copied her own. “No one equals her,” wrote a journalist for The Times Dispatch, “No one rivals her.”

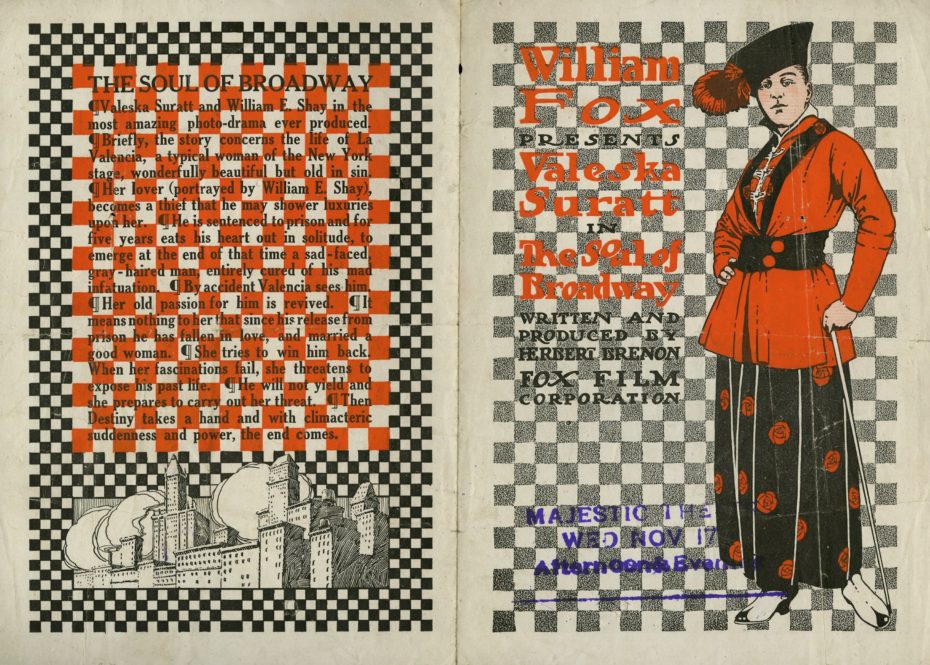

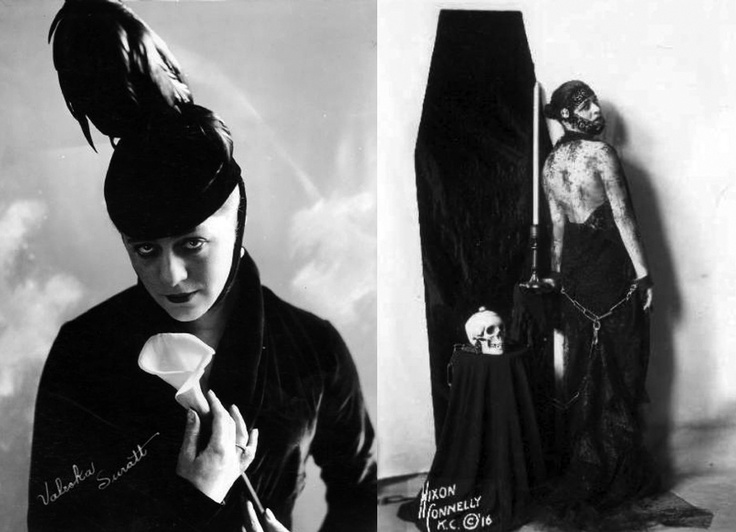

Surrat’s last film.

Suratt died at age 80 in Washington, D.C., and was buried back in Terre Haute, Indiana, and while we may not have her films, the actor left behind a legacy we can still learn from, and that is perhaps best expressed by journalist Esther Linder: “[These] vampire ladies of the screen,” she wrote in June of 1917, “have maintained [themselves ] unbreakable and inscrutable. Quietly and secretly they have gone on their way…successfully evaded all the attempts of prying persons to inquire into the secrets of their power.” In other words, ladies: never forget that wearing the dress and calling the shots aren’t mutually exclusive.