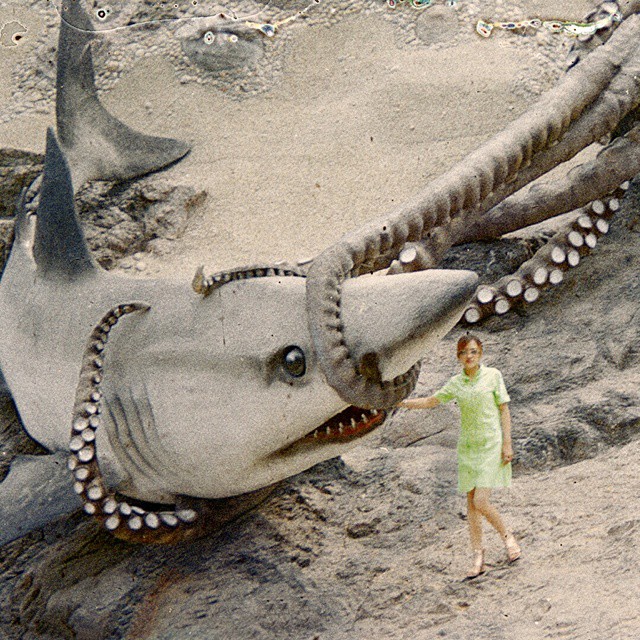

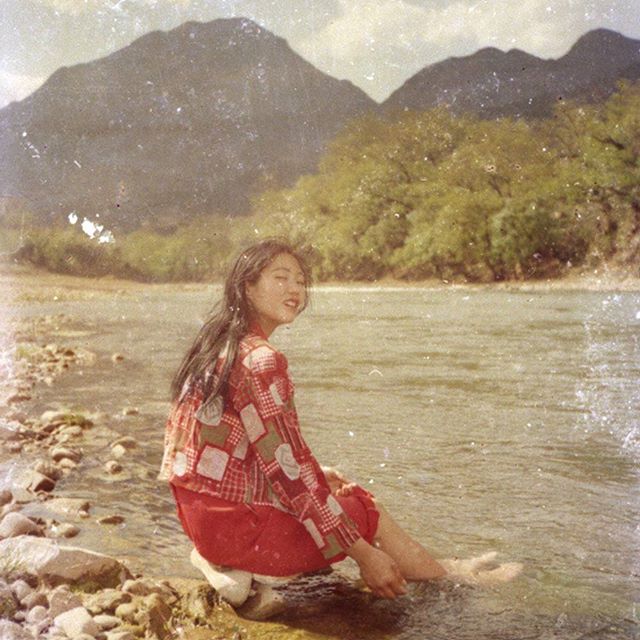

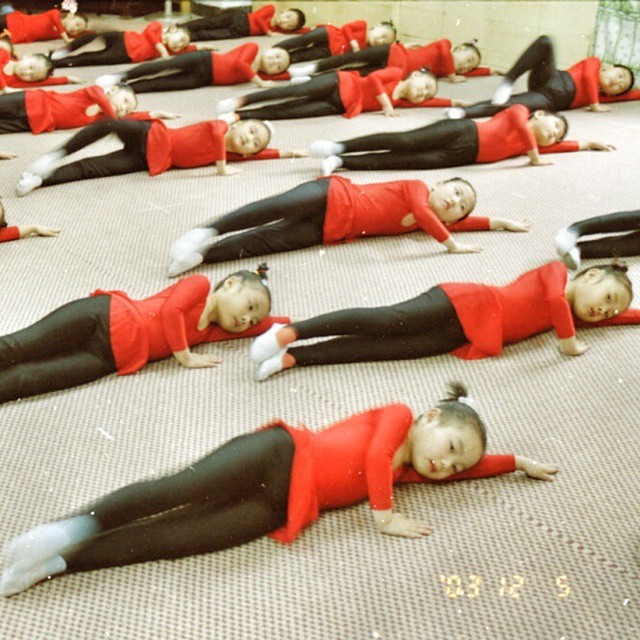

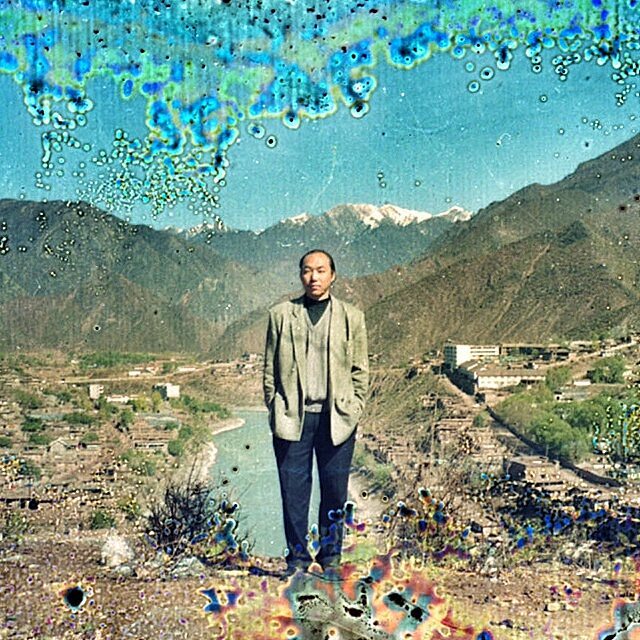

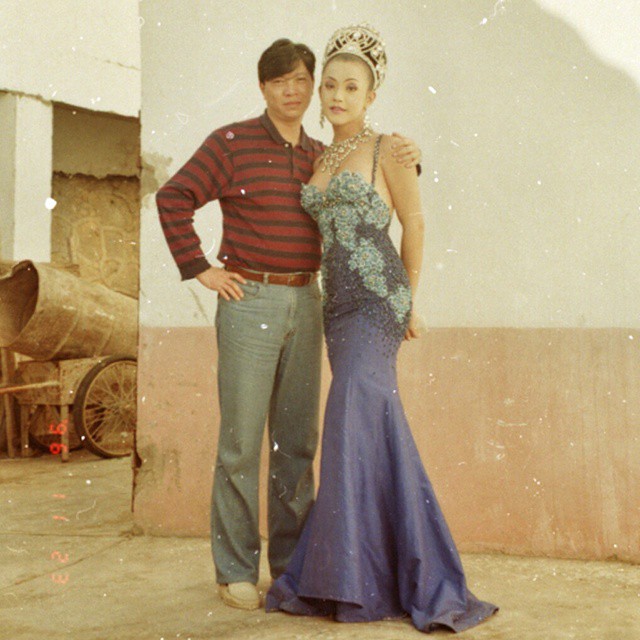

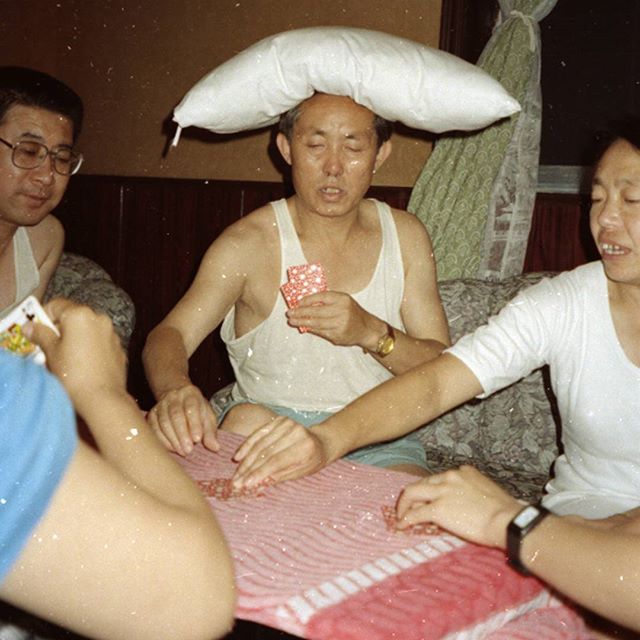

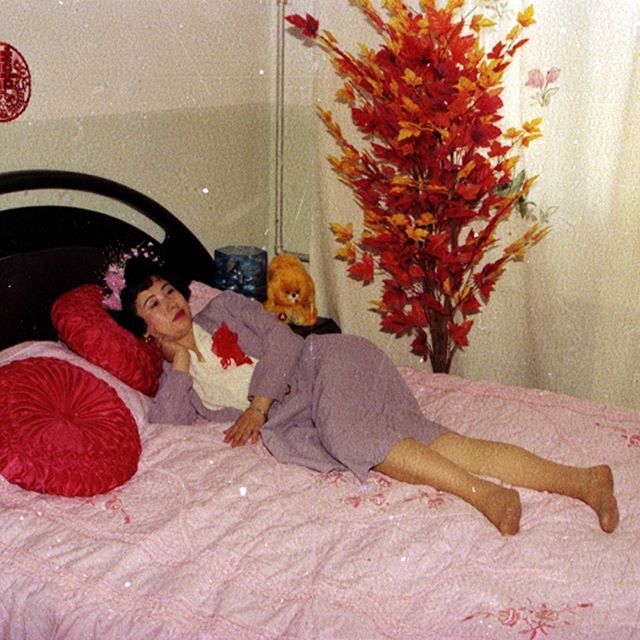

What do giant sharks, gymnastics, and a banana-eating competition have in common? They all inhabit the fantastic world of “Beijing Silvermine.” For almost a decade now, this has been the curious project of French photographer Thomas Sauvin, who has been on a tireless mission to rescue and revive the millions of 35 mm negatives floating around Beijing’s black market recycling plants. And it’s almost impossible not to fall in love with the enigmatic band of characters and places it brings together…

Thomas buys negatives by the kilo from Beijing’s clandestine recyclers who collect trash containing silver nitrate such as x-rays and more interestingly, film negatives. If Sauvin doesn’t rescue them, they’ll simply end up soaking in a tub of acid for a few days before they’re reduced to nothing more than a black powder (silver nitrate), which can then be sold off for cash to laboratories. You could say he’s in a league of his own when it comes to hunting for the treasures, and with the takeover of the digital camera, film negatives are becoming rarer than ever.

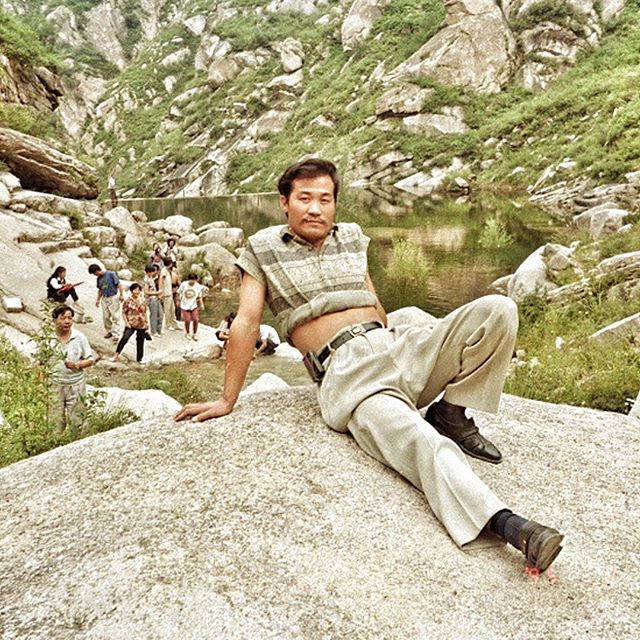

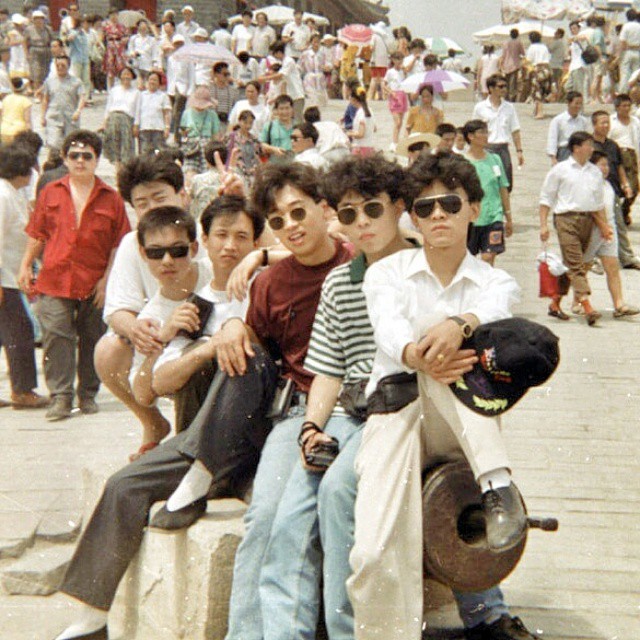

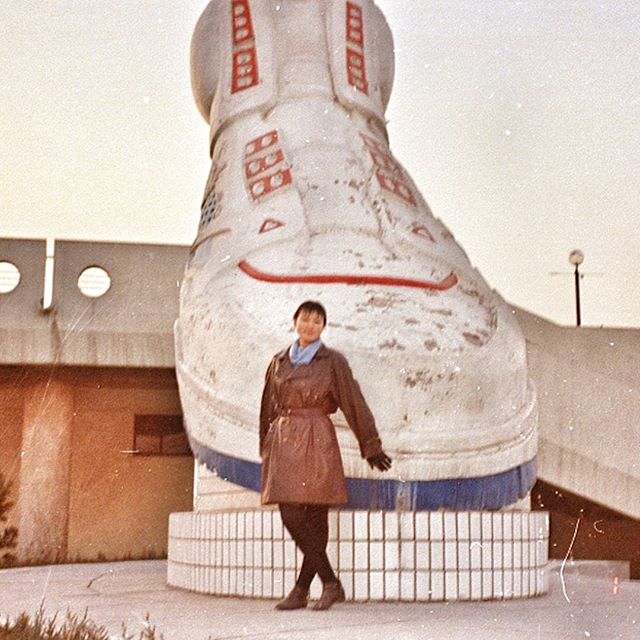

Sauvin’s project now consists of an archive of up to half a million photographs, dating from 1985 (when the first mainstream Kodak camera was produced) to 2005. In other words, they hail from the post-Cultural Revolution years that opened up China’s economy and changed consumption patterns (and saw karaoke bars and giant theme parks flourish).

The photographs (and their photographers) are all anonymous – and in truth, that’s the key to the project’s charm. Beijing Silvermine isn’t about putting faces to names.

“I often hear people saying that these images show a face of China they haven’t seen before,” Sauvin told The New Yorker in 2014, “The quantity of images involved allowed me to tell not individual stories but something more universal.”

Sauvin’s goal? To make sure we don’t forget what those seemingly silly theme parks represent: a hallmark transition for not only China, but the world. Sure, in our memories those years seem only a stone’s throw away, but they’re not, and so much of that period is being thrown out with the trash.

Archives and preservation projects like this tend to focus on much older photography– the black & white and pre-war stuff. If not for projects like Beijing Silvermine, these snapshots of more recent times are destined to become little more than a black powder used for chemical reactions.

Instead, Sauvin has decided to give them a visible, engaging platform– which just so happens to be Instagram. Sauvin has been collecting the images since 2009, but it wasn’t until 2014 that he decided they needed their own Instagram account, where he constantly curates his latest finds.

With a prominent spotlight on China for the future, don’t be surprised if the pertinence of this collection to the current sociopolitical climates becomes more apparent. As we try to further understand a culture that is so rapidly become a part of ours, it’s one of the many reasons we’ll be keeping our eyes on this Insta-gallery, with the primary being a little simpler: don’t throw away the good times.

Visit Beijing Silvermine’s Instagram account here, and learn more about Sauvin’s passionate project on his website and in the video below: