Anaïs Nin

Anaïs Nin is our favorite breed of artist: the kind who just can’t be bound to a single era, movement, or category. Diarist? Definitely. Muse? To many, most notably American novelist Henry Miller. Yet her oeuvre spans a good portion of the 20th century, and includes everything from those notorious diaries (about bohemian Paris in the ‘30s, Miller, etc.), works of creative non-fiction, poetic erotica, and (drumroll) some seriously trippy electro music.

Yup, you read correctly. In 1952, Nin dropped an electro track that could give today’s Coachella-bound DJs a run for their money: the song, “Bells of Atlantis.”

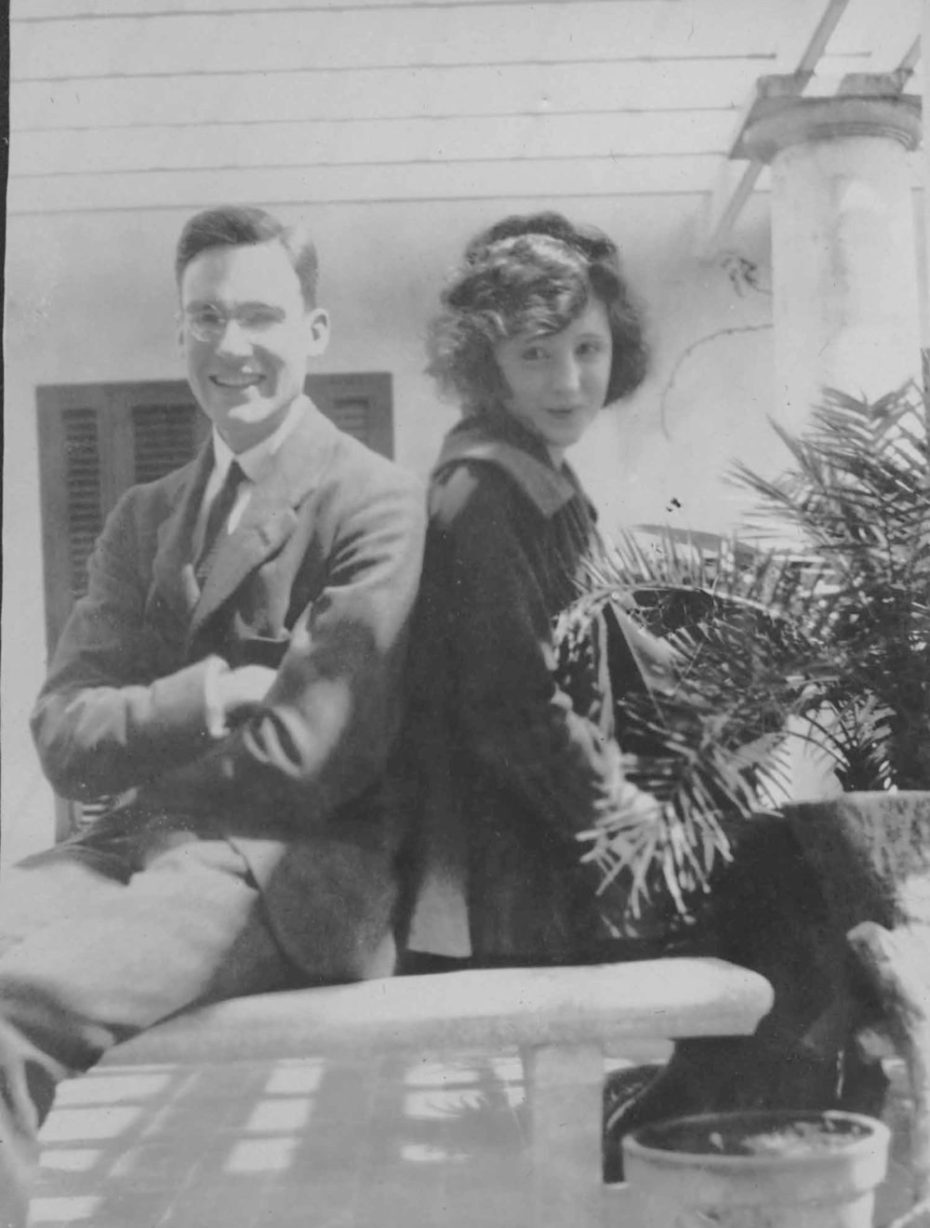

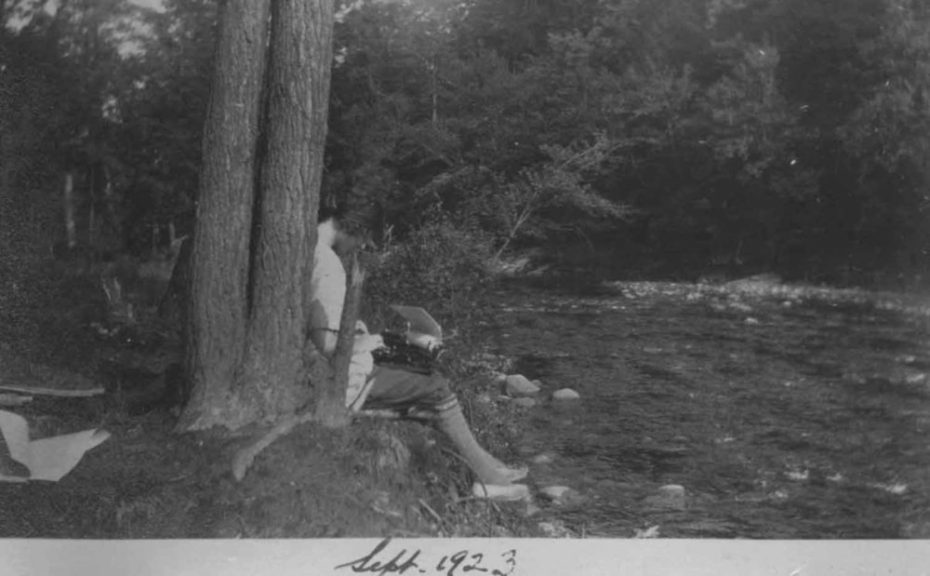

Anaïs and husband Hugo in Havana, 1923

To understand how the heck Nin arrives at the world of what we’ll go ahead and call “Impressionist electro,” it may help to first understand the importance of two crucial fixtures of her life: music and water.

Born in Paris to a Cuban-Spanish father (her mother was Dutch and French) who was himself a talented pianist and composer, Nin grew up to love the the Impressionist compositions of artists like Claude Debussy, whose songs she mentions in her works like A Spy in the House of Love, and whose sinewy, arabesque nature inspired a good deal of her own writing style (as would Jazz in her U.S. years). She was also a pretty good Flamenco dancer.

©AnaisNinFoundation

When afflicted with Cancer, Nin even decided to have speakers installed above the bed in her Silverlake, Los Angeles home specifically so she could listen to Debussy while dying.

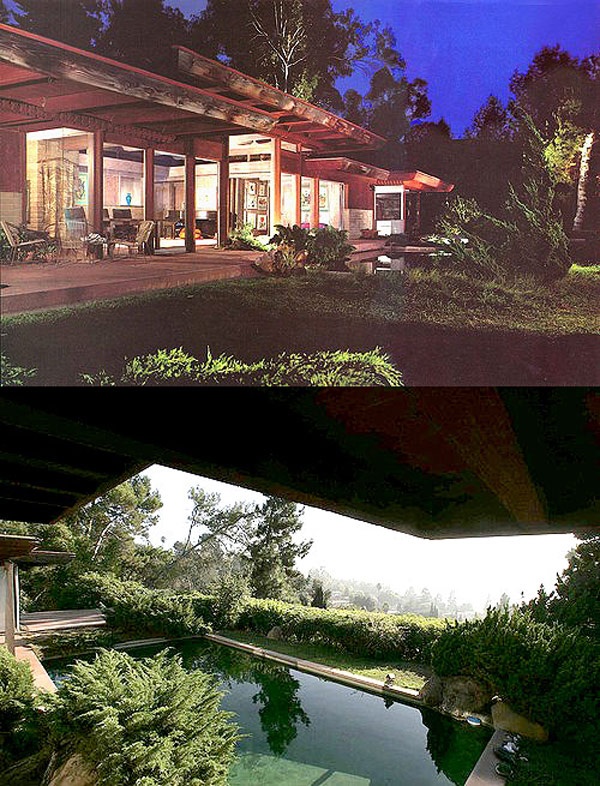

The Silverlake house.

The house in LA brings us to the importance of water in her life. While the artist may be famous for the years spent at her bohemian estate in the Paris suburbs, the Los Angeles home where she spent her final years became an extension of her obsession with water; the house’s pool, for example, was a key element of its overall design (in which Nin has a tremendous role) by architect Eric Lloyd Wright (yes, of that Wright family).

Nin writes by a river, 1923. ©AnaisNinFoundation

“The water makes me think of my first break with my roots,” she says in a ’70s documentary about her life, sitting pool-side, “[It] was taking the ship from Spain to America, which was when the Diary began. That was my first journey…which was also a bridge, and the breaking of a bridge with Europe and my father. I don’t know if I kept from that time the love of water as the most important element in my life, or with travel…I have a great love of journeys.”

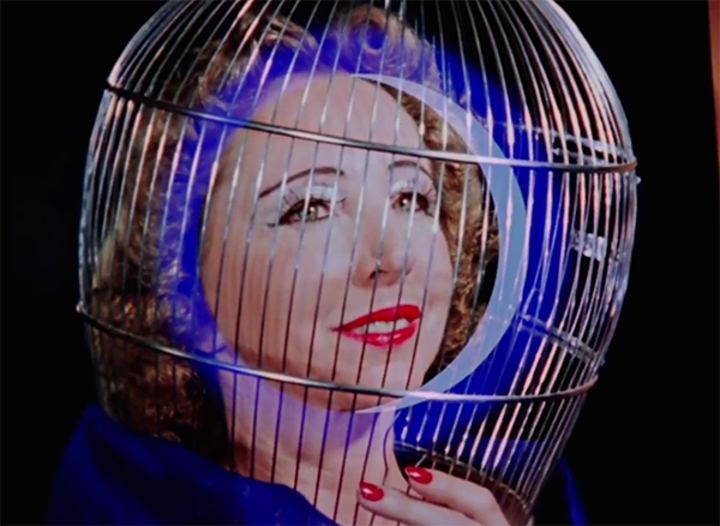

Nin at her Silverlake home in the ’70s.

Enter Bells of Atlantis, which was a collaborative electro-project with Nin, her first husband, Hugo Guiler, and the couple’s friends (also a married couple) Bebe and Louis Barron from Chicago, Illinois.

Hugo, a banker, was devoted to Nin until her death in 1977 and was himself a creative spirit who produced numerous engravings, drawings, and films. He even produced cover art for Nin’s works under the nom de plume, “Ian Hugo,” and when he needed an electronic base for the visuals he created for Bells of Atlantis, the Barrons were a natural fit.

©AnaisNinFoundation

The Barrons were true pioneers of electronic music, and one of the crown jewels of their auditory collection is the soundtrack for the 1956 thriller sci-fi film, Forbidden Planet. “[It] was the first major motion picture to feature an all-electronic film score,” clarified NPR in 2005, “[It] predated synthesizers and samplers.”

Bebe and Louis Barron

Initially, electronic music was nothing more than a hobby for the Barrons, who were gifted a tape recorder for their wedding and proceeded to capture candid moments with friends, at home, and at parties. But one thing led to another, and pretty soon Louis was devouring books on electronic circuits, and hay-wiring his own to create avant-garde sounds; he’d create tubes and oscillators while Bebe modified the loops and funked-up the tapes. Eventually, the couple moved to New York and went on to work with John Cage.

“The music by the Barrons seems to perfectly match the mood of the visuals, and the entire film really captures, in my opinion, the essence of the book that inspired it, House of Incest,” explained Nin’s editor, Paul Herron, when we asked for his two-cents on the song.

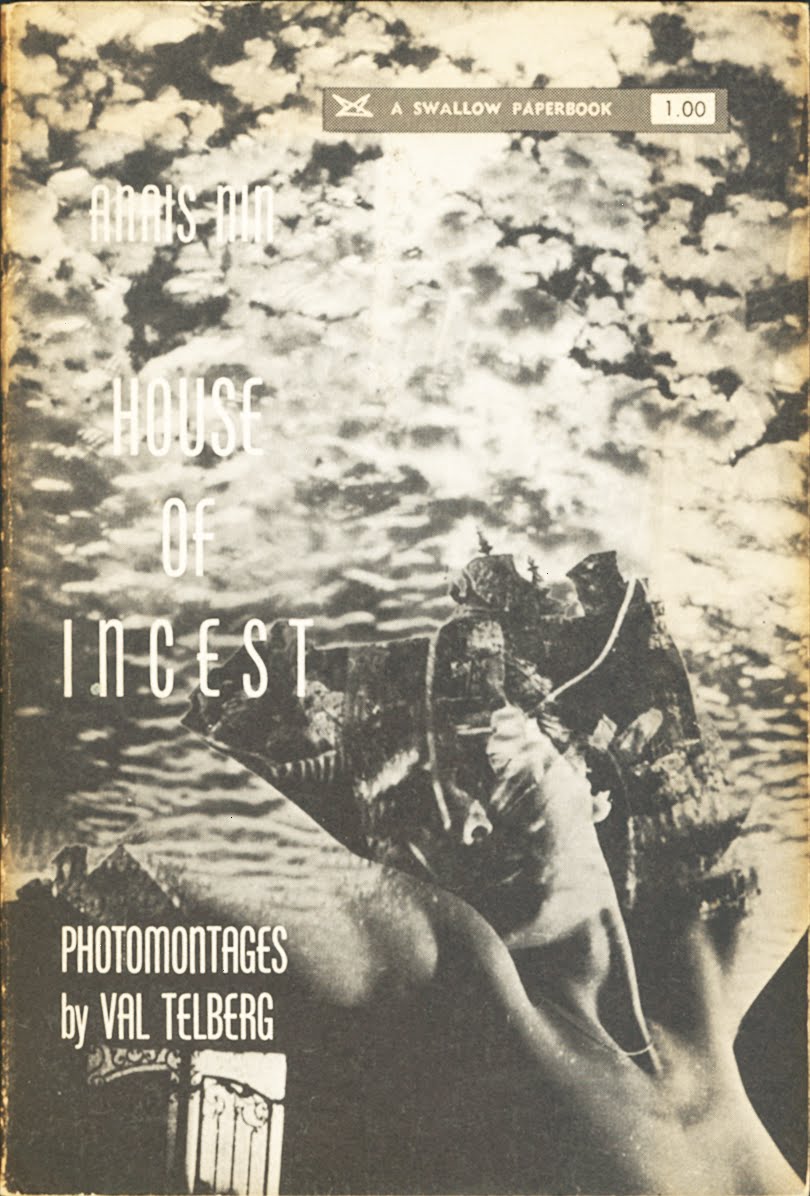

Indeed, Bells of Atlantis was first inspired by Nin’s 1947 prose-poem, House of Incest, which (spoiler) isn’t actually about incest, but rather taking the reader on a surreal, oneiric journey through what Nin describes as the narrator’s “escape from a woman’s season in hell” (sounds fun, right?). In truth, it’s a remarkable artefact from a period in which Nin was honing her psychoanalysis and dream-study skills (cue some tutelage under Freud’s disciple Otto Rank, a Pandora’s Box of daddy-issues, etc.).

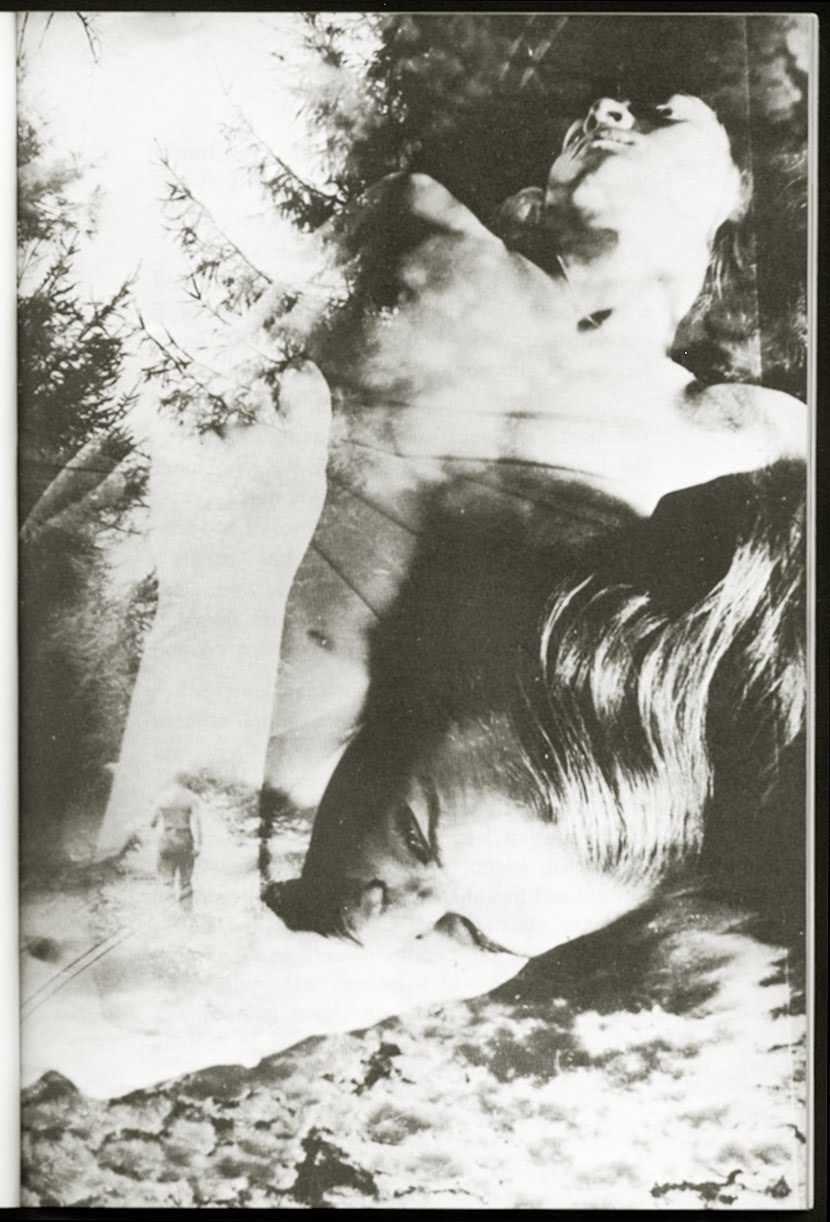

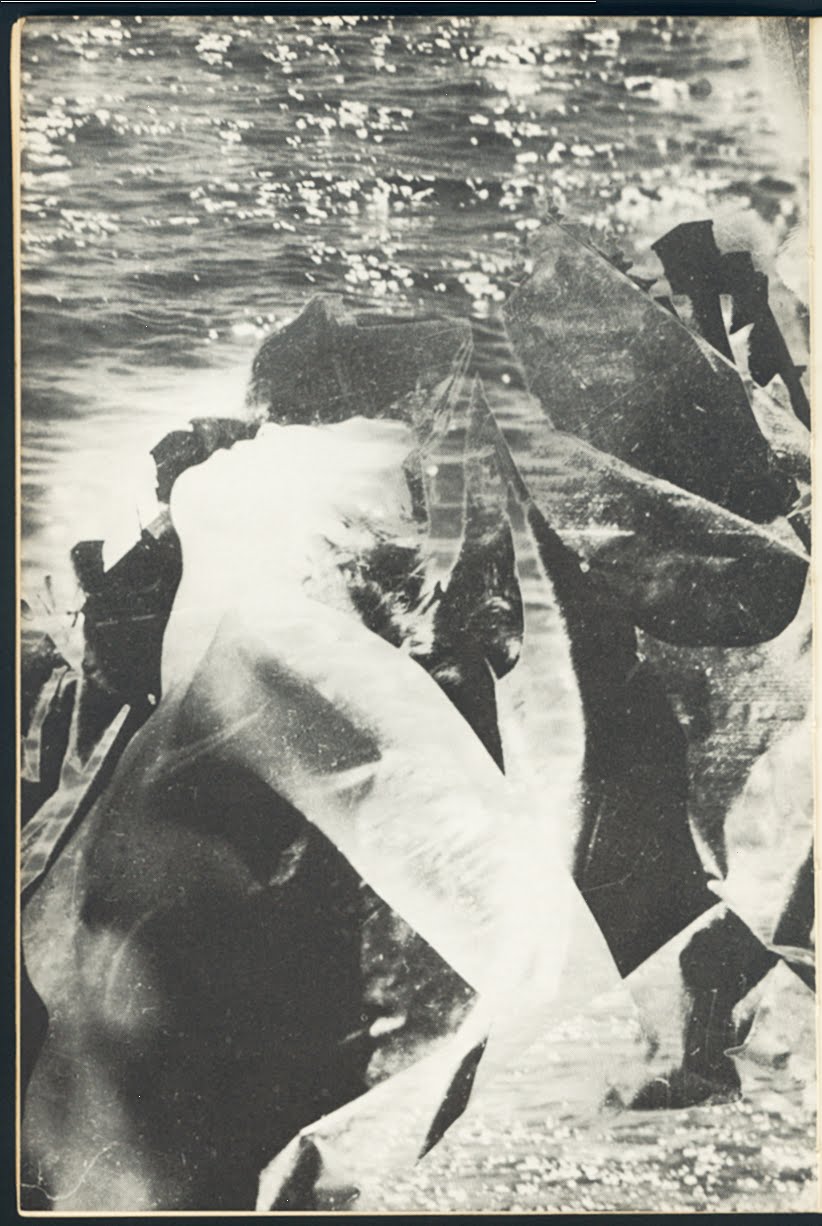

In other words, Nin channeled her courage and creativity to put her what she called her interior, “feminine” journey to the page. For the author, it was liberating. For critics, scandalous. Naturally, the the collages accompanying her book were fabulously out-there:

When Nin lent her voice to Hugo’s images and the Barron’s background music, the result was a poignant, perfectly psychedelic trifecta. A few minutes into the film, one starts to see shadowy figures flash together while electronic sounds — that could just as easily belong to a space alien as they could a submarine — provide the perfect backdrop for Nin to recite excerpts of her book with a vibrating, aquatic timbre.

“There is a lot of [Nin’s spirit] in there,” concludes Herron. “She is the figure Hugo captured with his camera on a Mexican beach, where they found a boat’s skeleton.” It’s a beautiful slice of an exciting creative period for the couple, not to mention the fact that, says Herron, “Hugo used superimposed films manually—which is practically a superhuman feat.”

Any traces of linear narrative, plot, or logic fall by the wayside in this visual song, and our only job as listeners and viewers (absorbers, let’s say) is to let Nin’s words guide us on a spatial journey into this recesses of her mind — and eventually, our own. Dive in yourself by checking out the track:

By Mary Frances Knapp, our Californian in Paris & beatnik at heart.