Born in the darkness of South African gold mines during Apartheid, “gumboot dancing” sprung from the basic need for exploited miners to communicate in what was a harrowing environment, where they were forbidden to even speak to one another. Workers decided to let their boots do the talking for them, and developed a kind of “morse code” from the noises made by the stomping of their rubber “Gumboots” or “Wellingtons.” What became their form of communication in the underground took “body language” to whole new level and inspired an entirely new form of dance…

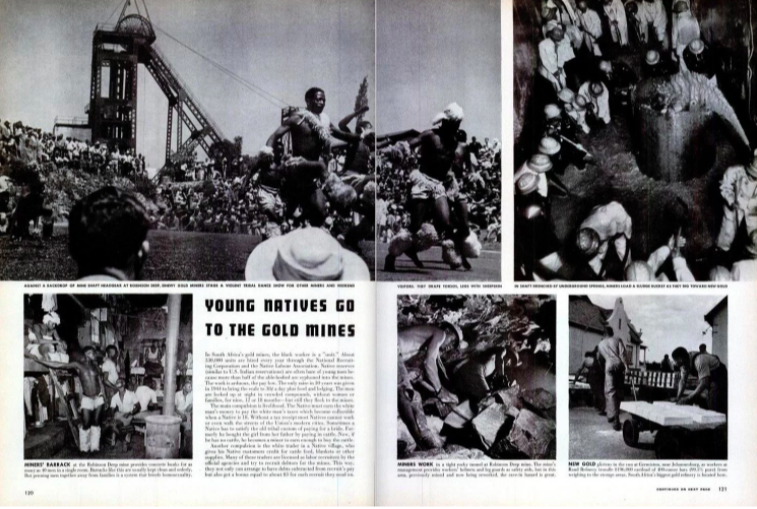

It all started with the discovery of gold in Johannesburg in 1886 – a major chance for economic growth, no doubt, but at a very steep environmental and humanitarian cost. The government realised it could exploit black workers by offering them work in the mines, and paying them far less than white Afrikaners.

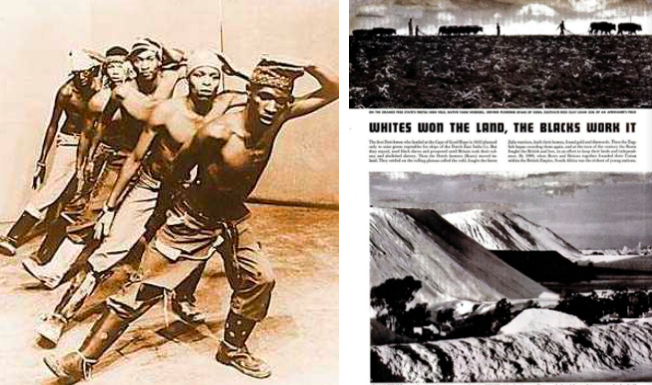

Tribesmen on their way to the mines.

The government also introduced new taxes that, quite simply, left the tribesmen with no choice other than to leave their villages to work in the city. Needless to say, decades of Apartheid perpetuated the discrimination and abuse.

“It was very, very frightening to go there,” former miner Nicolson Mkananda told the Financial Times in 2014, recalling the blatant mistreatment and humiliating conditions imposed upon the miners in the ’60 and ‘70s.

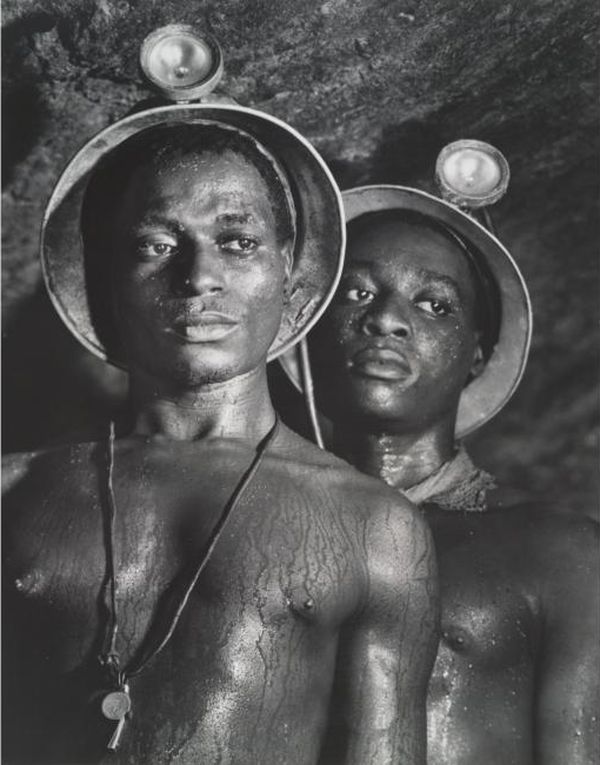

Johannesburg miners (1950).

With limited access to water, the mines’ 95 degree (Fahrenheit) temperatures could prove fatal for the workers, who laboured in chains and under unsanitary, dangerous conditions where basic mobility, passable air quality, and free speech were compromised. That’s where the boots come in.

LIFE, 1950.

At the height of the migrant labour system, by slapping their gumboots to send messages to each other, the enslaved workers were rattling off the very chains that bound them.

Gumboot dancers (left).

Gumboot dancing served a very practical and basic need to communicate, but it was also a testament to the miners’ strength and staunch fight for self-expression. Gumboot dance-offs were a cathartic, community-building tool that mixed traditional forms of dance from the various tribes. In other words, even during the darkest hour, rhythm and joy found a way.

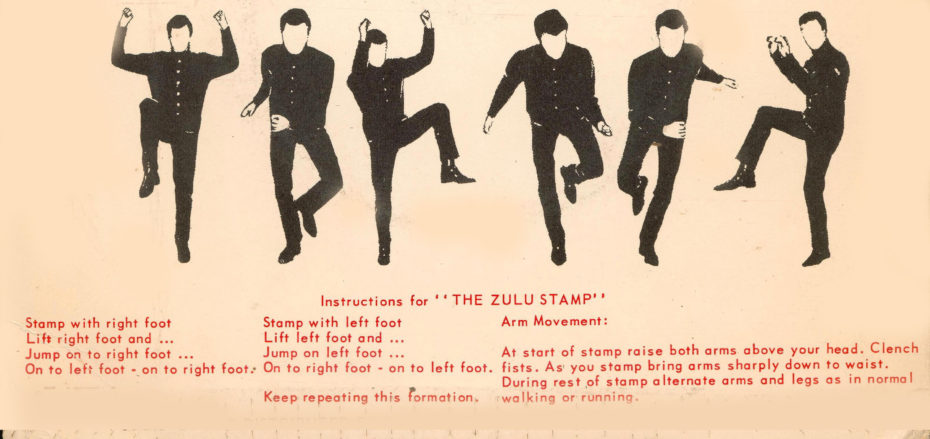

The legacy of gumboot dancing travelled out of the mines and into mainstream culture– for the better, and for the worse. Case in point: Zulu-appropriated dance instructions catering to white occidentals in the 1960s (pictured above).

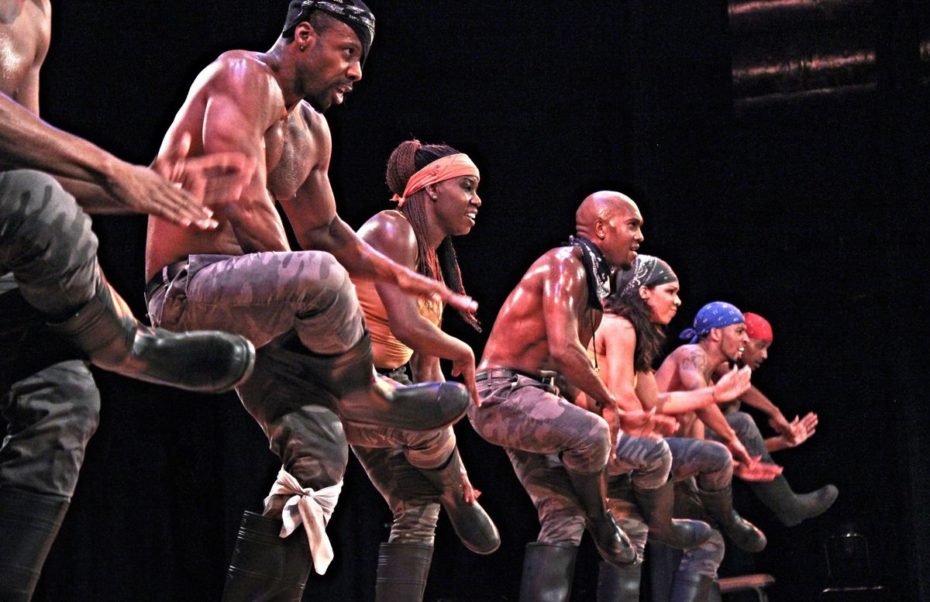

The gumboot-inspired dance moves of contemporary hip hop and breakdance, on the other hand, are a positive example of the dance’s importance and posterity within black communities. South Africa’s government has also recognised the dance as national treasure, and it’s performed by professional and amateur troupes worldwide — always with wellies, and often with a hard-hat to pay homage to the miners preceding them. Have a look for yourself: