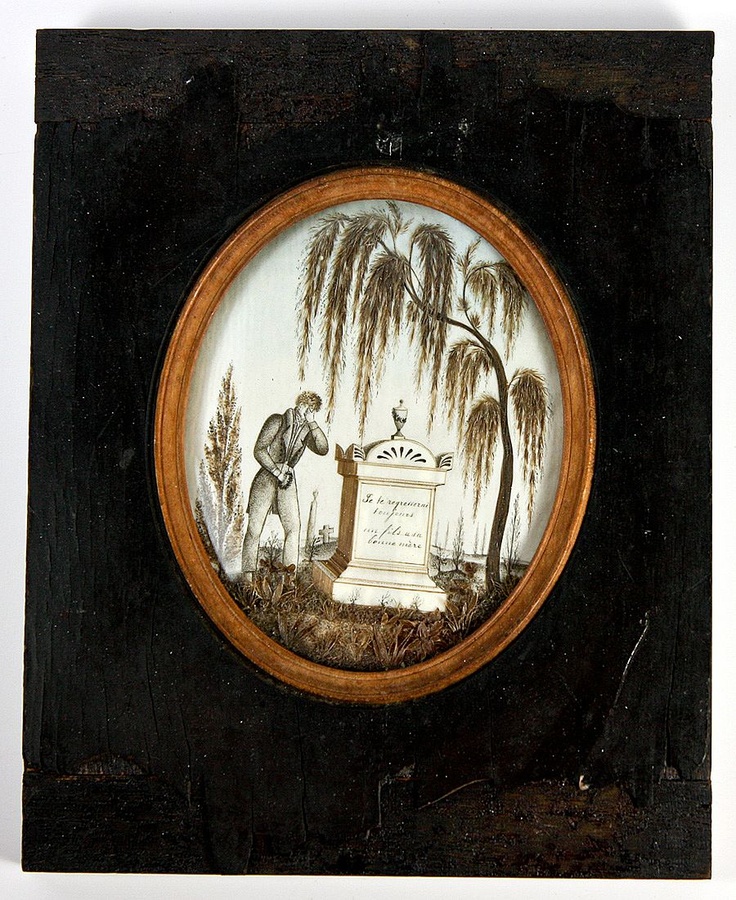

Meander through enough Sunday flea markets, and you’re bound to come across a Victorian grief shrine every now and again. They’re quite hypnotising objects, with their lacquered wood frames and bulbous glass encasing tiny flower-baskets, spindly trees, and elaborate landscapes. Take a closer peak, and you’ll realise you’re looking at a shrine made of someone’s actual hair.

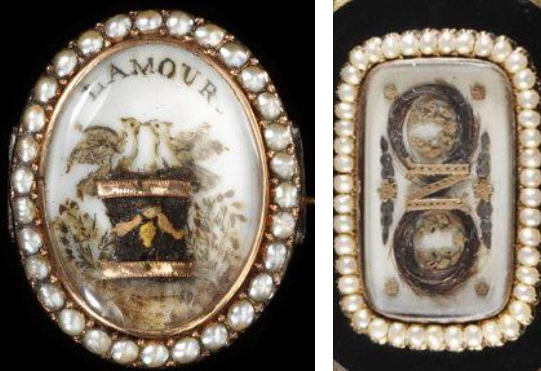

Making shrines and jewellery out of human hair was already a hot hobby in the Victorian age. Exchanging locks of hair with your friend, family member, or lover was as common an act of affection as, say, liking a pal’s Instagram pic today…

Even Napoleon got in on the trend, and requested that his hair be woven into bracelets for his relatives to remember him after his passing. But today, we’re honing-in on the hair jewellery and shrines made in memoriam of loved ones. On that subject, Queen Victoria is a good place to start.

Grief simply set the tone for the final years of the Victorian era in both the present-day European Union and United States. In 1861, the unexpected death of the Queen’s husband, Prince Albert, took an immense toll on the Monarch. Suddenly, grieving the loss of her husband’s death became a second full-time job.

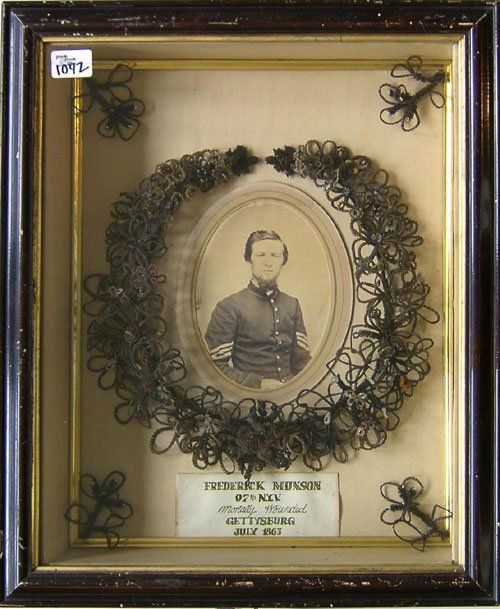

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the American Civil war was under way. To this day, the war remains one of the most intense periods of domestic carnage and loss in the U.S.. The act of crafting a grieving shrine out of the locks of a loved one’s hair was not only cathartic, but created a tangible memory of sorts for loved ones lost in battle.

That delicate weeping willow? Human hair.

Families would go to great lengths to have craftspeople make up intricate scenes paying homage to their kin, creating heirlooms for generations to come. The act even became a rather competitive game, with each member of the community seeing whose shrine could be biggest…

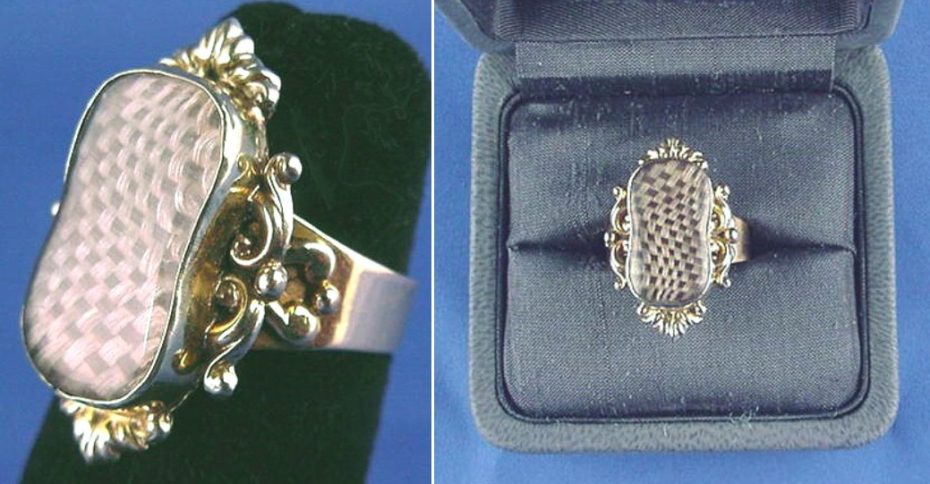

That’s not to say there were’t smaller, more portable efforts made, namely in the form of rings and brooches. According to mourning-jewellery specialist Erica Weiner, “before photography came along, [mourning jewellery] was the main way that people remembered their departed loved ones.

These items weren’t limited to women, either; men could have memorial cufflinks or pocket watch fobs with parts of the deceased person’s hair braided in.”

There was really nothing off-limits when it came to the shape the shrines could take– many of them incorporated crosses, bows, braids, and even took the shape of snakes…

A quick search on eBay and we found a pretty extensive collection of this stuff for sale, ranging from $5 to $500. Some of the hair “craftsmanship” is really quite mind-boggling…

Today, the shrines might strike one as rather macabre, but it helps to contextualise the craft in relation to its time. The tradition thrived in a period when loss was part of one’s everyday life, and in that way, contributed to the normalisation of one of the touchiest topics to date: death.

Who knows, maybe you’ll be inspired to take home your locks from the hairdresser the next time you’re due for a trim…