This was just too interesting to save for Halloween. It all started when I stumbled upon a photograph of a something called a “mortsafe“– mort being the French word for death and safe implying there was something in need of protection from theft. Indeed, these graveyard oddities were once intended to deter body snatchers from stealing the remains of the deceased. But who on earth would need to steal dead bodies from their graves, you ask? Oh, just doctors and qualified professionals of the 19th century medical community, paving the way for pretty much all the modern medicine we benefit from today.

So there was a time, when the trade of stolen bodies was a thriving and lucrative business, powered by a demand from some of the most respected individuals in society. Body snatchers, or resurrectionists, as they were also known, were commonly employed by medical schools and anatomists to advance their knowledge. Bodies were snatched regularly and without consideration and the epidemic resulted in “a harvest” of about 500 bodies per school year in some cities. It was such a problem that a necessity to guard the graves of your loved ones became commonplace across Britain and America. As a new-found interest in anatomy and surgery was on the rise, corpses and their component parts suddenly became a commodity.

19th Century operating theatre, England

The demand was high but the supply of cadavers was low, which sent medical schools on a constant hunt for new bodies. By law, only the corpses of executed criminals could be used for dissection. During the 18th century, hundreds had been executed for trivial crimes, but by the 19th century, only a few dozen a year faced capital punishment in comparison, which made finding recently-deceased bodies for the growing medical community far more difficult.

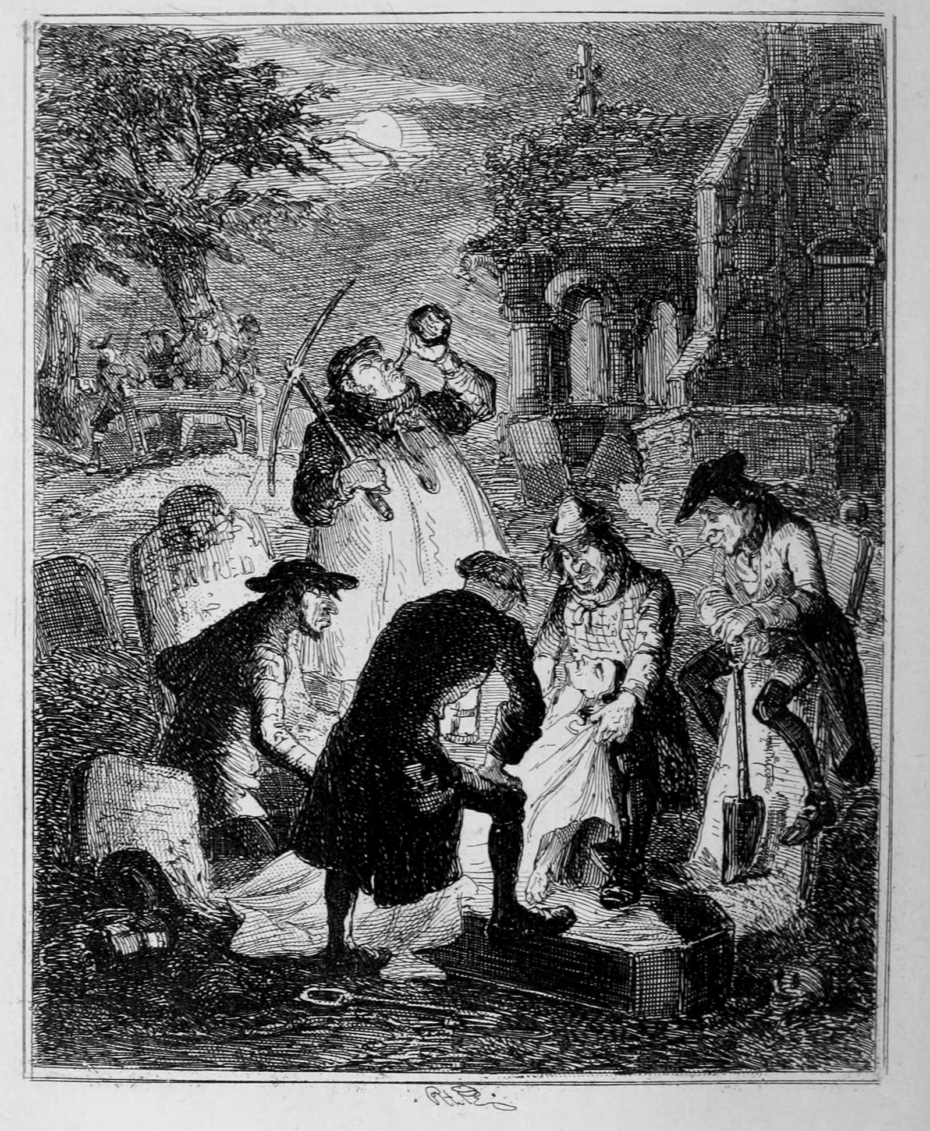

Resurrectionists often worked in gangs, finding corpses through a network of informers who took a cut of the proceeds. They worked at night, and had various methods to dig the graves and hoist bodies out of the ground quickly and quietly. The entire process could be completed within 30 minutes. More enterprising resurrectionists were known to hire women to act the part of grieving relatives and to claim the bodies of dead at poorhouses. They would even attend funerals as grieving mourners to stake out the scene and warn the body snatchers of any problems they might encounter.

A painting on the wall of a pub in Penicuik, Scotland

Meanwhile, authorities conveniently looked the other way. Since corpses were not technically viewed as property, the resurrectionists operated in a grey area and body snatching remained quasi-legal; an open secret, ignored by governments as a necessary evil. There was a pub in in East London, called “The Fortune of War”, famous for its role as a meeting place where resurrectionists would sell cadavers to surgeons. They could be paid up to 20 guineas per corpse. For perspective, a servant working for a wealthy household would earn a single guinea per week. Some surgeons at universities even notably complained of body snatchers hiking up prices during local body shortages.

Many well-known medical schools were notorious for body snatching activity. Harvard had a secret anatomic society called the “Spunkers” (speaking or writing the name was prohibited) and its purpose was to participate in anatomic dissection, using cadavers that they themselves had procured, shovels in hand. One famous American physician, Charles Knowlton was imprisoned for two months for “illegal dissection” after graduating with distinction from Dartmouth Medical School.

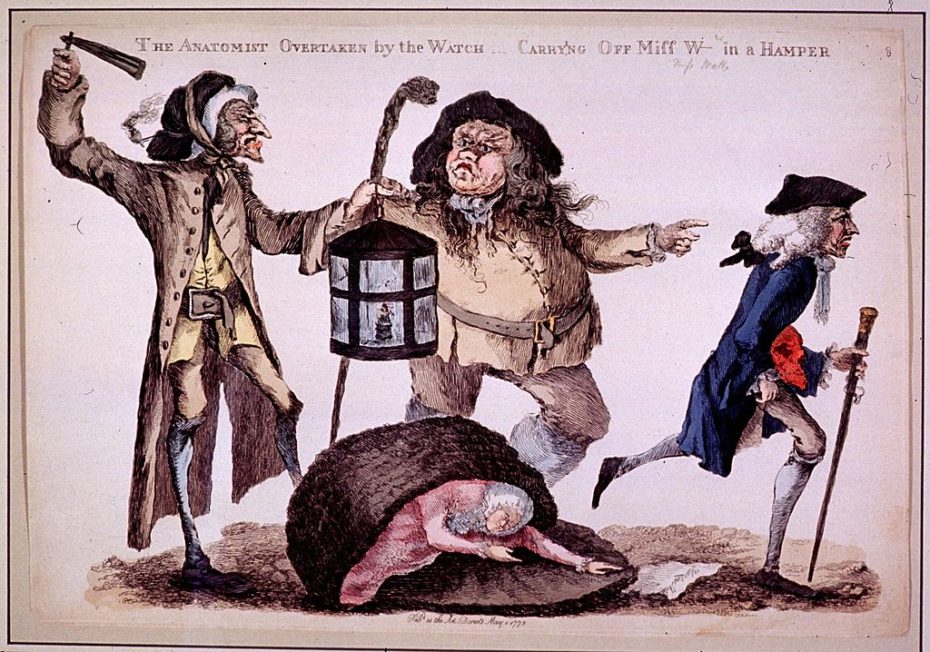

© Wellcome Library

Even the body of an Ohio congressman John Scott Harrison, was snatched in 1878 for the Ohio Medical College. His body was discovered by his son John Harrison (brother of President Benjamin Harrison). John travelled to the college with search warrants to find his father’s naked body hanging from a rope beneath a trap door. A missing body buried next to the congressman was also later found preserved at the medical college of the University of Michigan.

In a high-reaching conspiracy in Philadelphia, it was even found that the mayor of the town was settling disputes between schools over who should receive an allotment of bodies.

Logierait Parish Church, Scotland

The mortsafe was invented in about 1816, a contraption designed to protect graves from disturbance, placed over coffins for the first six weeks after burial (prime picking time for anatomists looking for fresh bodies), then removed for further use. Churches often bought them and hired them out and many notable examples can still be found in Scotland, where grave-robbing was particularly rife, all close medical schools. Edinburgh has a gruesome case of 16 murders that took place in 1828, in which the victims’ bodies were sold to a local doctor for his anatomy lectures.

Watch tower in Dalkeith Cemetery, Scotland

Not everyone could afford a mortsafe. The poor placed flowers and pebbles on graves to detect disturbances or dug heather and branches into the soil to make disinterment more difficult. Communities grouped together to take turns on graveyard watch and watch-houses were sometimes erected in cemeteries. In response to public outcry and revulsion to body snatching, laws were eventually passed that gave freer licence to doctors and medical schools to dissect donated bodies.

Now, if you’re still reading, I’m sure you’ll join me in my relief that our doctors aren’t bodysnatchers anymore. Try that for a dinner table conversation starter.