For those whose taste in fairytales favours a darker touch, we’re traveling to the far reaches of Eastern Europe, and into the enchanting world of animator Jiří Trnka. The late Czech animator (whose name is pronounced “Yershy Trinka”) created nearly two-dozen films over his lifetime, from folksy gems like Grandfather Planted a Beet (1945) to the gutsy anti-Stalin short, The Hand (1965).

Craftsmanship ran in Trnka’s blood. He was born in Bohemia in 1912, where his grandmother sold toys for a living and his mother worked as a seamstress. “Even as a child he was making puppets,” explained his daughter, Helena, to the Novy Domov journal in 2012, “He had access to fabrics and other such materials and he taught himself to sew. He was also a very skilled self-taught wood carver.”

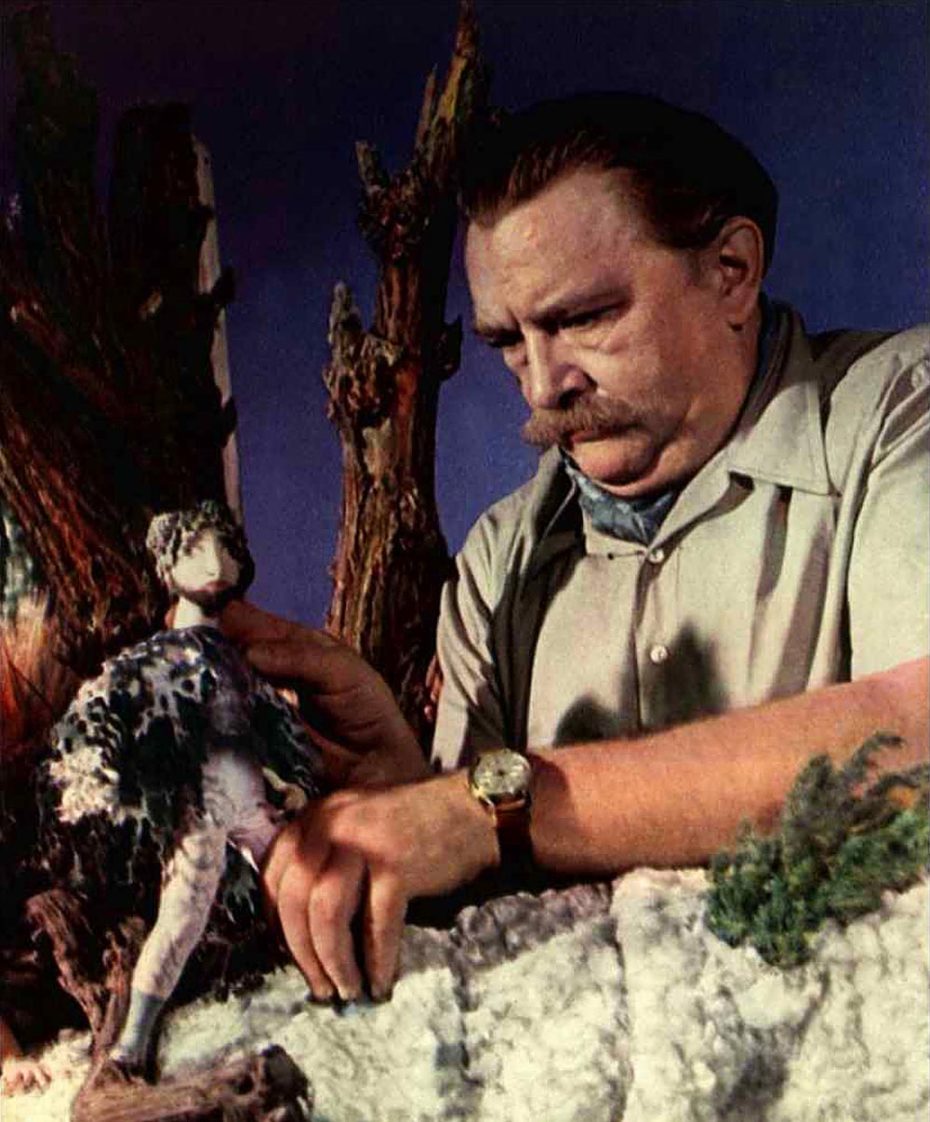

Trnka (left).

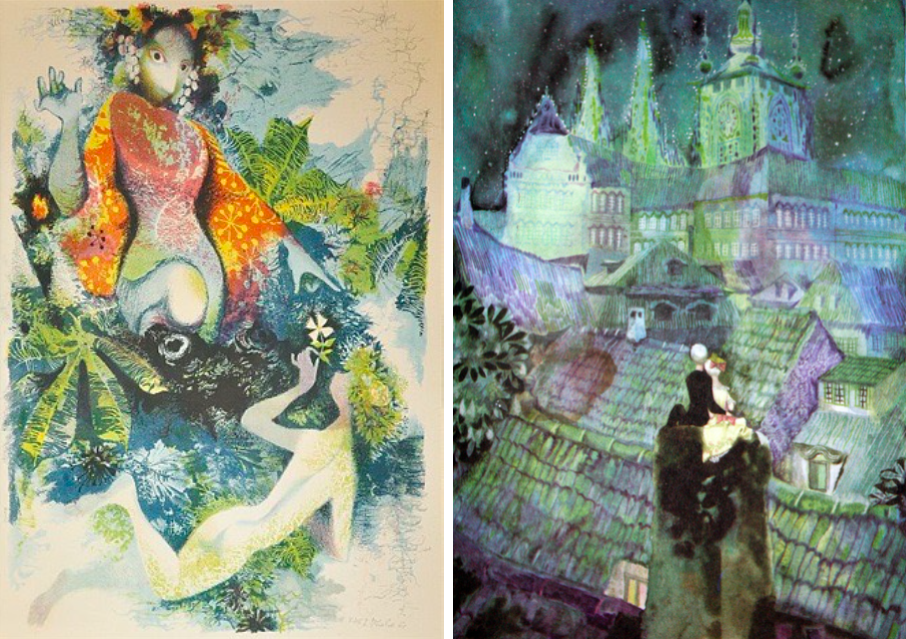

After bouts as a pastry chef and locksmith, he finally began to pursue a full-time career in the arts, and graduated from Prague’s Academy of Art and International Design in 1935. Most of his early work consisted of illustrations for the children’s tales of Hans Christian Anderson and other fairytales, and after WWII, he co-founded the studio Bratři v triku (“Brothers in Tricks”) with animators Eduard Hofman and Jiří Brdečka, which is still in operation today.

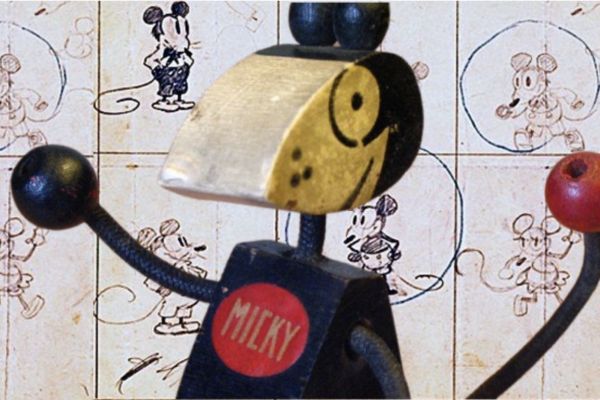

His first puppets were made of wood, and incorporated simple materials like burlap, and found natural objects (i.e. acorn nut hats).

“[He was] the first rebel against Disney’s omnipotence,” explains biographer Jaroslav Bocek in Jiri Trnka: Artist and Puppet Master, “By painting the dreamlike aspects of reality, Trnka was doing the same as the surrealists…his roaming brush reflected a child’s roaming mind, with its inability to concentrate, its tendency to fantasy.” But it was Trnka’s adult-targeted puppetry that really took things to the next level.

A Trnka film was rarely dubbed with voice-over, as the animator found it rather tacky and preferred to incorporate music, odd sounds, and the nuances of lighting to lead his narratives.

The puppets’ heads also never changed, and “[Trnka] gave [their] eyes an [indefinable] look,” explained his colleague, Bretislav Pojar; “This gave one the impression that the puppet hid more than it showed, and its heart of wood stored even more.”

1959’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream remains his greatest masterpiece– at least, in matters of sheer production skill and scale. The stop-motion film runs for over an hour, and eschewed the typical English Renaissance-vibe for a quasi-Mediterranean set. Trnka was a true perfectionist, and sometimes he would end up cutting scenes that took days to film.

“The Hand” (1965).

The results were hypnotic. Flowers blossomed from the puppets’ hems, and intricately sculpted fairies descended from the studio’s ceiling – it was truly a sight to behold, and a big hit with the public.

But there’s also a darker side to Trnka’s work: an undercurrent of anti-Stalin, anti-Big-Brother, anti-communist sentiment. Consider 1962’s “The Cybernetic Grandma,” which is basically an Orwellian bedtime story in which a boy is nearly traumatised by a robotic chair with angel wings that speaks like his grandmother.

By the time the Communist Party had taken control of Czechoslovakia by 1948, Trnka had become quite the local and international animation star. The communists decided to subsidise the artist’s consequent output — but at steep creative cost for the puppet master, who was not a fan of their meddling.

“The Hand” (1965).

Trnka’s last film, “The Hand” (1965), was essentially a parabolic middle-finger to the communists. The story is centered around a humble potter whose life is ruined by the demands of the state; he’s literally snatched from his home, trapped in a giant birdcage, and forced to sculpt. The Potter momentarily escapes the Hand, but eventually it’s the death of him – it even nails his coffin shut in the final, chilling scene.

Trnka passed away in 1969, and his funeral procession in Pilsen drew an impressive public crowd; here was man, so unmistakably Czech, who had broken into the global animation scene with charisma and pride for his culture. As an artist, he used the seemingly infantile medium of puppetry to stress the importance of individuality, free expression, and, above all, of the possibility for beauty to surface in the most unlikely (and often terrifying) of circumstances.

Watch the master at work below: