Stepping inside Maison Gatti is like entering Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory for Francophiles and furniture connoisseurs alike. Nestled in the Parisian commune of Fontainebleau, the atelier is the last of its kind — and one of the few surviving sources for authentic Parisian bistro chairs.

As such, Gatti has become the guardian of a long-standing craft; a tradition that has made Paris’ renowned terrace culture what it is today. “They’re as Parisian as the grandes boulevards,” owner Benoît Maugrion explains to us. He’s one of the owners of the nearly 100-year-old business, which “In a way,” he says, “gave us the grandes boulevards.”

He’s not kidding. The chairs’ natural habitat is the inimitable Parisian terrace. They were born when Haussmann built his sprawling boulevards, which would become the new ‘highways’ of Paris and home to the city’s first big brasseries. “They’ve always been made of this rattan material, [an import] from the French colonial presence in Asia,” says Benoît, pointing to an immense pile of the cane-like material, “they’re light, sturdy, and [supple].”

In other words, a match made in heaven for a sidewalk café. “But they need a mild climate, and to be taken inside for the night, at closing hour, to dry. There’s a [misconception] that they’re purely outdoor chairs.” In true French fashion, these babies need a little more pampering and “should absolutely not be stored on a wet lawn.”

The maison’s roots really stretch back to 1909, when Italian furniture maker Joseph Gatti immigrated to Paris. His dream was to make a family business that cherished “craft and connection”, says Benoît, whose own father worked in the atelier and eventually took over once Madame Gatti (the daughter of Joseph) passed away 25 years ago. “We were four people when my father bought it,” he says. Now, they’re nearly two-dozen.

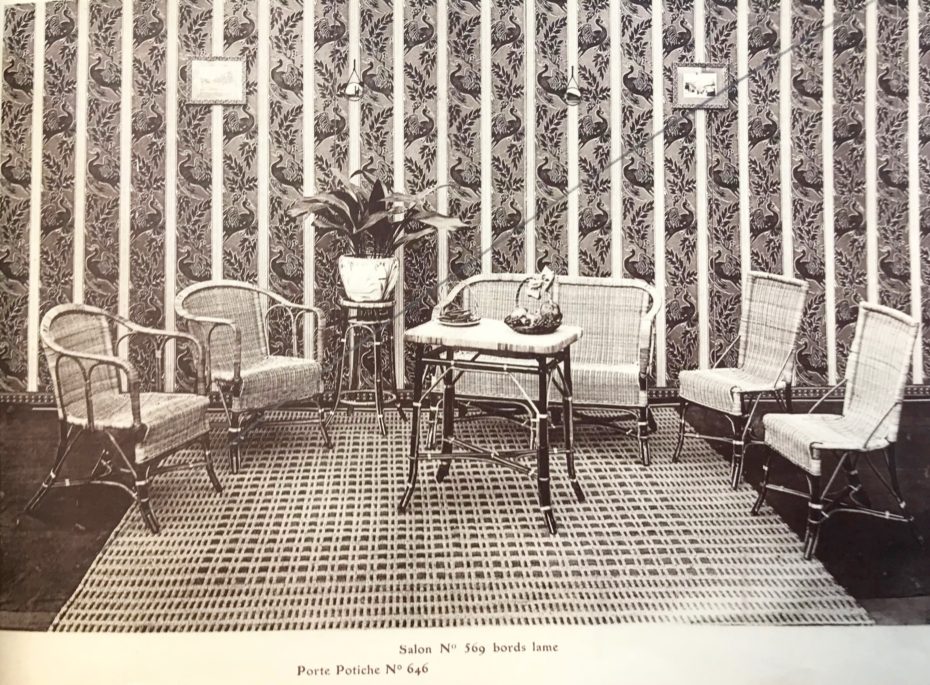

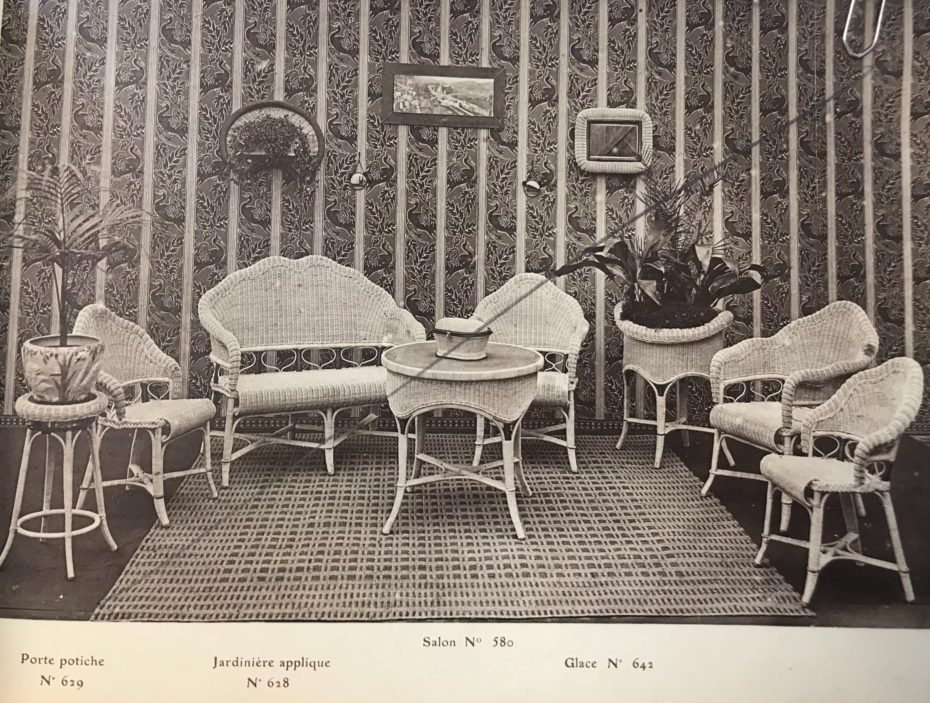

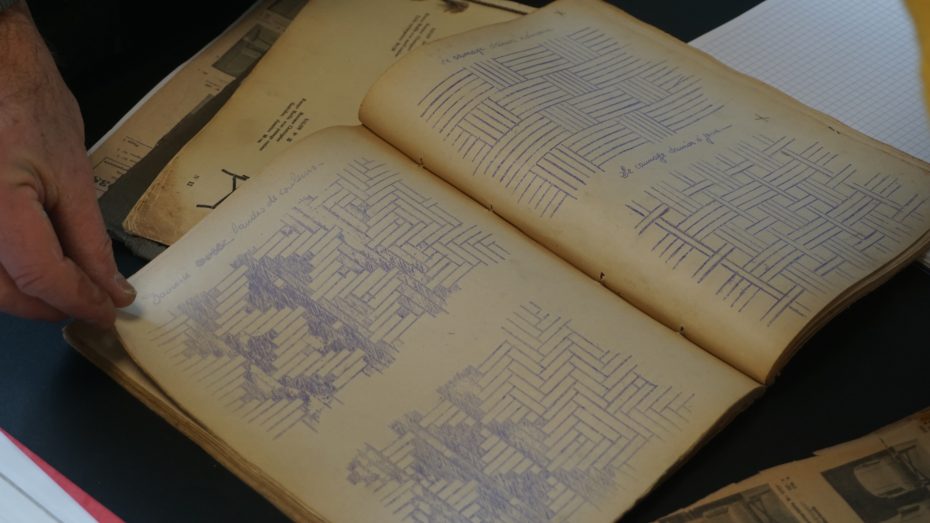

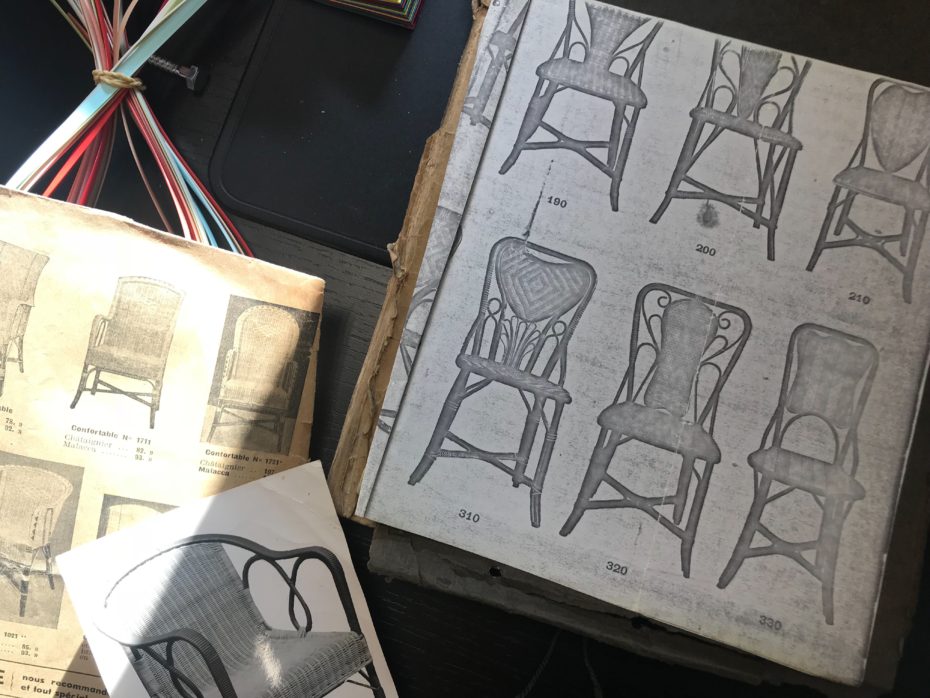

Gatti’s archives.

“In the 1920s, when it was officially founded, there were a hundred furniture makers like us,” says Benoît, who was entrusted to take to over the operation with his brother. “Madame Gatti had no children,” he says, “The chairs were her children, and she treated them well.”

The original atelier was also a child of the Belle Epoque, one of Paris’ most opulent eras. The houses were grand. The parks, vast and meticulous. “You’d order your Gatti recliners in the winter,” he says, “and they’d be ready in about three or four months for the coming season. No part of that process has changed [for us] , even though the times have. We’re still made-to-order.”

Our tour of the production line essentially follows the birth of a Gatti chair – of which there are about 30 models and woven patterns.

When asked where those patterns come from, Benoît says they “can be quite antique, sometimes ancient.” Their names? “Usually chosen for the patron who ordered them,” which sure puts the “Bonaparte” model in a new spotlight…

Above all, the atelier has the ambiance of a place where things are made not just by hand, but with heart and soul. The employees are singing, smiling, and each proudly stationed at his or her own area of expertise.

Coils of rainbow resin are snaked into dollops and stacked high, while towers of chairs pop up around every corner like little Leaning Towers of Pisa. We meet a woman who can weave a seat in 45 minutes, and the charming Juan, who has been an atelier fixture since the reign of Benoît’s father:

Back in the day, there was even a training school for those looking to work in the rattan furniture game. But by the 1950s, the number of flourishing factories had dwindled from 100 to 50, as did the need for a fully-fledged school. The emergence of aluminium was also a blow to the industry.

Nessy sizes-up the rattan.

Today, the Gatti factory doubles as the only school for aspiring artisans, who are trained for three to five years before joining the storied team. The requirements? “Only a passion to work with your hands,” says Benoît, “for the craft.” In truth, he says, it’s getting harder to find new talent – if only for the simple reason that folks assume they don’t have what it takes. “Our doors are open to absolutely everyone who wants to learn.” Benoît mentions that he has a son, but he’s not sure if he’ll follow in his footsteps.

In 2013, a fire tragically destroyed the building and most of its treasured stock– and at the end of our visit, Benoît agrees to pull out the atelier’s Crown Jewels: the oldest remaining Gatti chair in existence (circa 1920), and the only archival documents they could save:

The oldest Gatti chair.

Gatti’s archives.

“Well, we’re a respectful, serious company” he concludes when we ask how Gatti continues to hold its own. Today their only competition is Asian manufacturers, he explains, who pose a real threat with their “low-cost imitations” of the Parisian bistro chair. “We know they’re not making true Gatti chairs,” he says, “We know the difference in craftsmanship.” So do Benoît’s clients, who hail from every corner of the world.

In front of the break-room.

Ask any Parisian where their best memories have been made, and it’s likely they’ll say en terrasse over (one too many) bottles of wine at a dimly-lit brasserie. Be it Hemingway’s Left Bank staple, la Palette, or Simone-de-Beauvoir’s Café de Flore, Gatti has always been there – literally, and figuratively – for support.

If you’re keen on owning a piece of Parisian history yourself, you can custom order a chair on Maison Gatti’s website. If you happen to be in Paris proper, you can also pick up a (rare) collection they created for the staple Pigalle boutique, Philippe Model maison at 65 Rue Condorcet.

And before you go, take a virtual tour with MessyNessy…