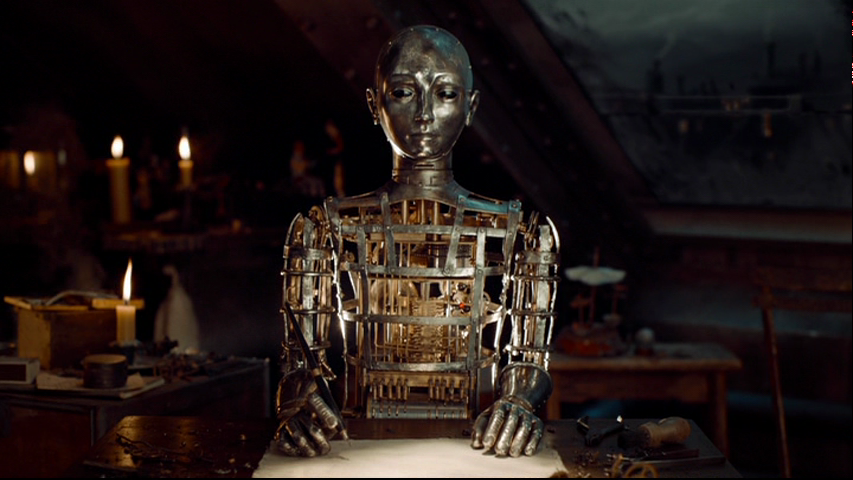

It’s hard to imagine that before the United States of America even became a country, a Swiss watchmaker had already created a machine with the capabilities of a modern programmable computer– in the form of a small boy. The 70cm-tall automaton known as “The Writer”, is an extraordinary but often forgotten anomaly of its age. So impossibly ahead of its time, even the creator, Pierre Jaquet-Droz, was fearful he might be arrested for sorcery when he presented his masterpieces of engineering to the royal courts of Europe. The most complex of his self-moving androids is now nearly 250 years-old; a machine that simulates human actions without electricity, controlled by a complex programming system disk fitted inside the carved wooden body of an extraordinary little child.

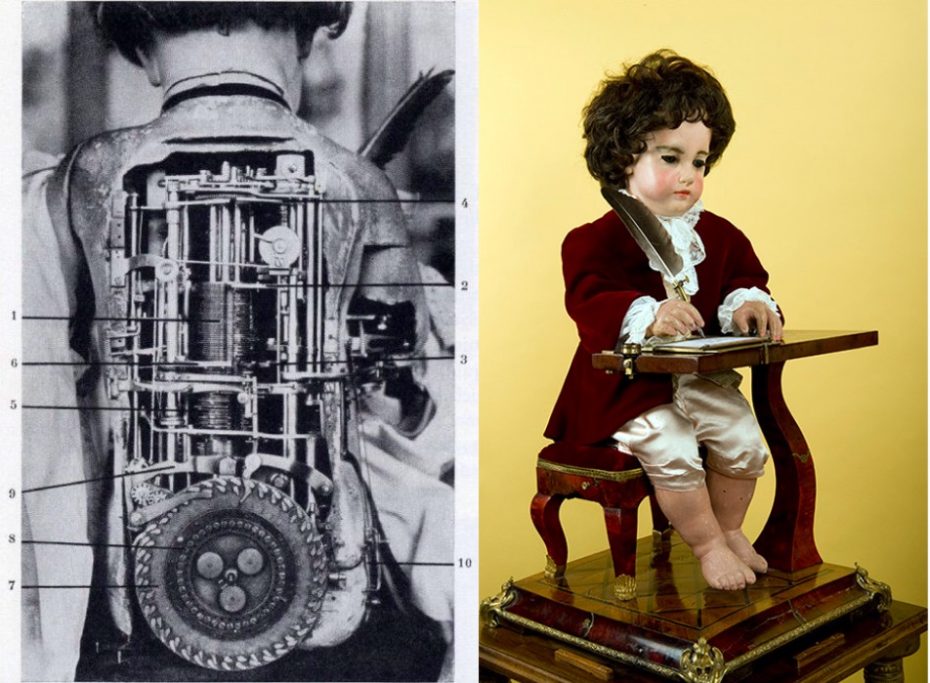

The first modern printer? The first true artificial intelligence? The Writer has written thousands of notes, using a goose quill pen that he dips in an ink well, then shakes his hand slightly to avoid spots of ink on the paper, before demonstrating his fluid and elegant penmanship as his eyes follow the text. He sits at a Louis-XV mahogany desk, wearing elegant period clothing which disguise a hidden door to his back that reveals a 6000-piece mechanism, computing his ability to trace the letters of the alphabet.

Okay, here’s where you geek out. In order to write any words, letter by letter over four lines, it uses an extraordinary system of 40 rotating cams that essentially work like a Read-only (ROM) data storage, mainly still used to store firmware or application software on computers today. The wheel controlling the cams inside the doll is a programming system disk made up of letters that can be removed, replaced and re-ordered to make any word or any sentence, allowing this 250-year old writer, to be programmed like a robot.

I can barely jam a USB cable into its port without getting frustrated and this thing was built in the 18th century? (And has better hand-writing).

The late 18th century was a golden age of automata (self-moving machines), and Europe at one time, was full of them. They entertained royalty, became tools of publicity in windows of grand department stores, and raised deep philosophical questions about the future of artificial intelligence even then.

But none were as complex as the little boy. Unlike all commercial automata of the time, his mechanism was placed inside his body and not attached to an external piece of furniture. It required unfathomable precision to miniaturise the mechanical wheels into such a small space while still synchronising the complex movements of the automaton.

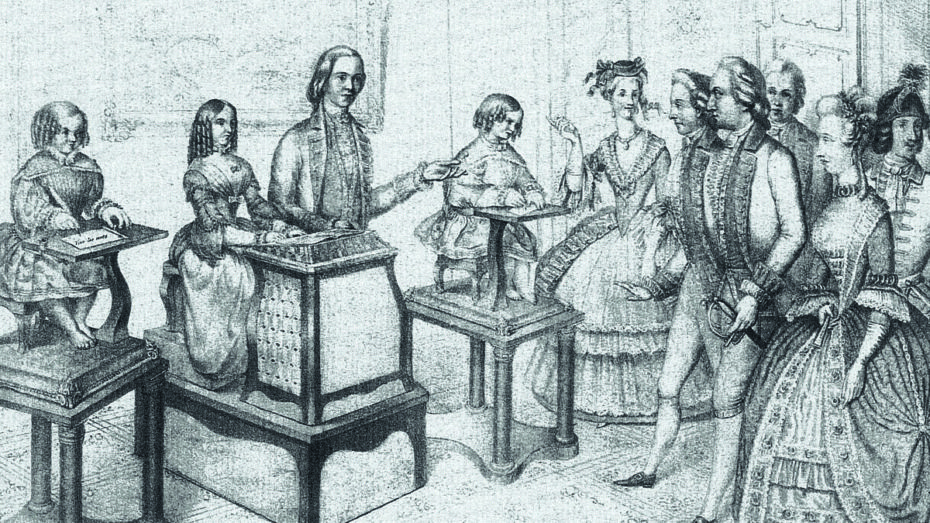

Pierre Jaquet-Droz constructed three highly complex models between 1767 and 1774, including the Writer, the Draftsman and the Lady Musician. He had set up his first watchmaking workshop at a farm in Switzerland and later travelled to Paris, where clockwork automata was in high demand and small family ateliers thrived. In 1758, he presented his earlier works to the King of Spain at his court, where he demonstrated a clock with a shepherd playing on a flute, and a dog guarding a basket of apples. When the King was challenged to take one of the apples, the dog threw himself on his hand, barking so naturally, that a hound present in the room barked back. Spooked courtiers left the room, accusing Jaquet-Droz of witchcraft.

But the engineer continued his demonstration for the King and his minister, the only audience left in the room. He challenged the minister to ask his automaton shepherd for the time. When he asked in Spanish there was no reply from the machine, but when the King addressed the shepherd in French, the shepherd replied with the time immediately. Having frightened everyone out of the room except the king, Pierre feared he would soon face the Catholic Inquisition on accusations of sorcery. He went so far presenting the inner mechanism of his devices to the Grand Inquisitor to prove the mechanism was moved entirely by natural means. Fortunately, his trip to Spain was a success and he returned to France rich and famous. His “Shepherd’s Clock” is still on display in one of the King of Spain’s palace museums.

With the money Jaquet-Droz earned from the Spanish King’s investment, he established a profitable company that would position itself at the forefront of technological advancement, and allow him to get to work on creating the most ambitious automat androids the world had ever seen, arguably still to this day. Come to think of it, he sounds a little bit like Steve Jobs.

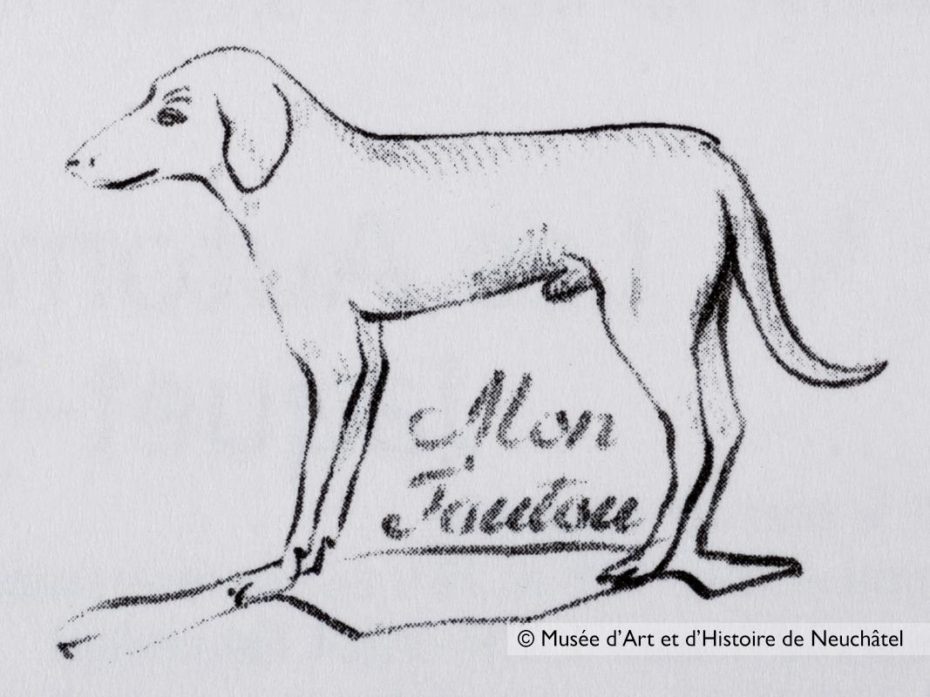

The Draftsman was his first automaton, similar, but slightly simpler, made of only 2000 pieces. Instead of writing letters, he used a pencil to draw four different portraits– one of the french King—Louis XV, a drawing of a dog with the inscription, a Cupid in a chariot pulled by a butterfly, and a portrait of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI.

A small device with an air bag, like a miniature pair of fireplace bellows concealed in his head, allowed him to blow the dust off his paper. The Draftsman was able also to raise his hand to examine his work with admiration or to correct a defect.

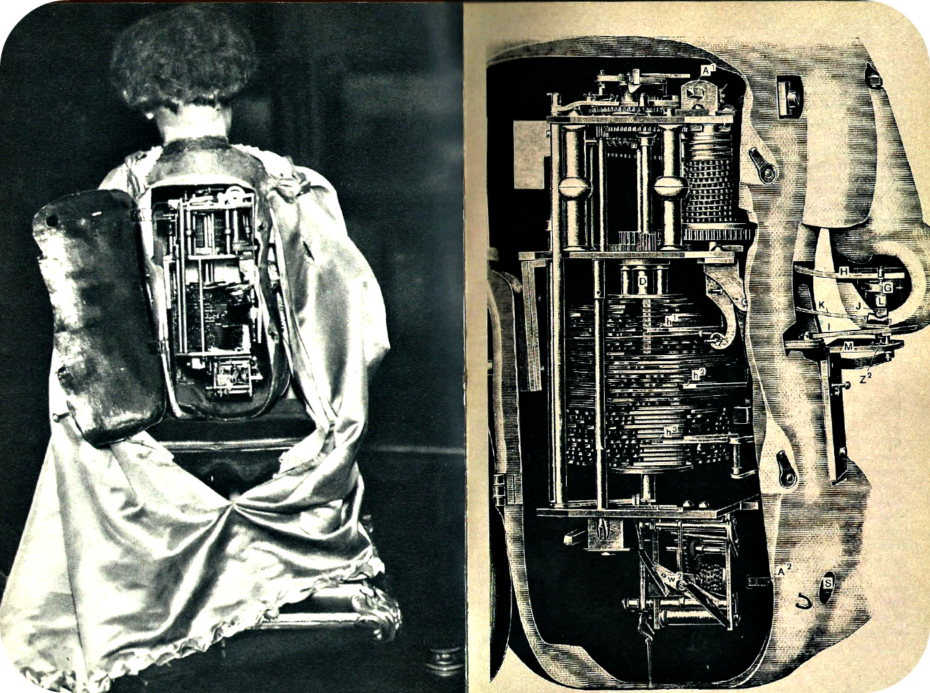

The Lady Musician played the organ– but not like a music box. The music is created by the automaton itself, which is programmed to press the keys of an actual organ. Her torso and her eyes replicate the movement of a human organ player.

All three masterpieces are housed at the Museum of Art and History of Neuchâtel, where they remain in virtually the same working condition as when they were first made.

After the Jaquet Droz company peaked in 1788 and was liquidated, remaining dormant for over 200 years until it was acquired by the Swatch Group in 2000. Rather than forgetting its roots, the company was returned to its origins and set up in Droz’ hometown and moved into its new Atelier in 2010.

Paying homage to the expertise and craftsmanship, the brand offers some truly unique timepieces, incorporating miniature painting, sculpture and engraving and even authentic automatons. In 2012, The Bird Repeater model was launched in the memory of Pierre’s popular 18th century singing birds. Having discovered the story of his automatons, I’m now lusting after a Jaquet-Droz watch and wouldn’t hesitate choose these timepieces over the latest technology on an Apple watch.

From the bestselling children’s novel ”The Invention of Hugo Cabret” and the Oscar nominated film ”Hugo” (both I highly recommend) to the computer device that you have at your fingertips this very instant, Jaquet Droz’ real-life mechanical marvels have inspired more than we probably realise. To imagine what he could have achieved in the 21st century, particularly in the world of artificial intelligence, is both intriguing and slightly unnerving (if you weren’t already creeped out by the inner-workings of his automaton dolls). Mostly, it leaves me wondering what other innovate masteries are being lost to time or hidden in obscurity? I’ll let you know…