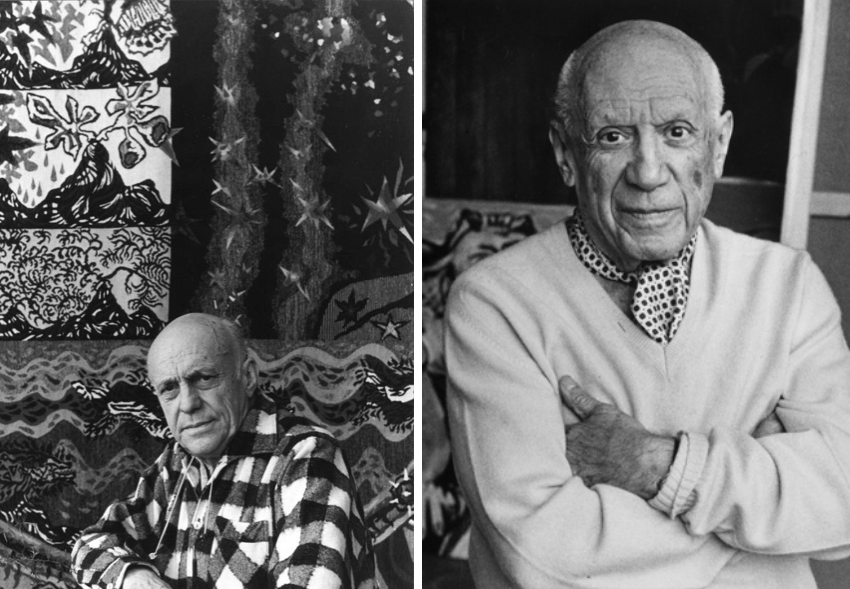

Picasso, is that you? You have to admit, Jean Lurçat (above) is almost a dead ringer for Pablo. Same stocky build, same receding hairline. Just swap the cable-knit sweater for a Breton-striped shirt, and boom. We did a bit of digging to find out who this mysterious dopplegänger was, and realised that Lurçat and Picasso have much more in common than just their looks…

Lurçat (left), Picasso (right).

Jean Lurçat

Jean Lurçat was actually one of France’s most groundbreaking artists during the 20th century, albeit lesser known than Picasso. Like the famous Spanish artist, his career took off with abstract and cubist painting before branching out into ceramics, mosaics, and jewellery making.

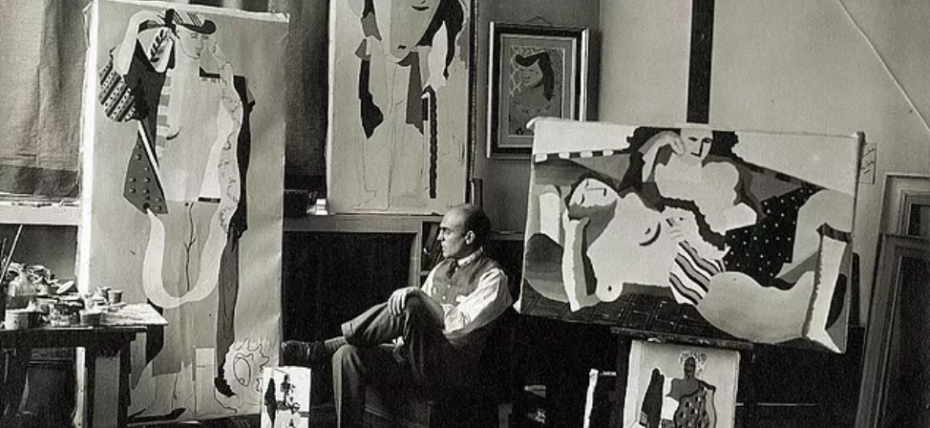

Young Lurçat (1931).

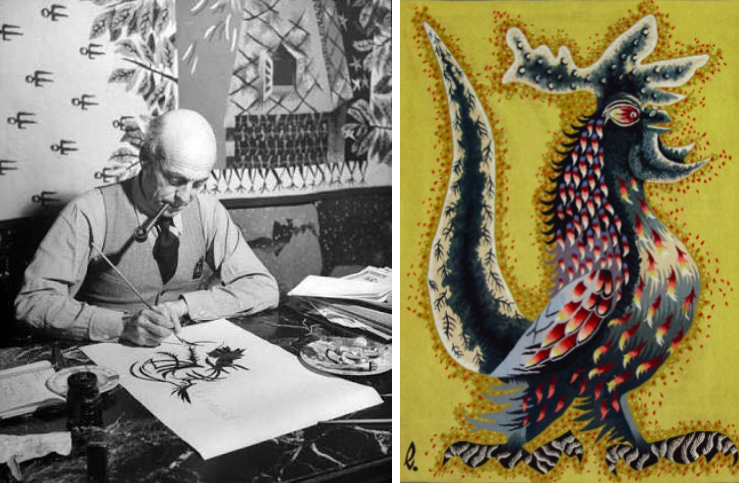

Then, there was Lurçat’s true forté: tapestry. His style was one in a million, at once Fauvist with its dramatic use of colour, Cubist with its jumbled figures, and borderline psychedelic in its imagery of flaming lions and rainbow butterflies. Think Picasso, but on acid.

“Our memories are often amassed of hallucinations,” explained Lurçat in the 1965 documentary about the trippy nature of his work, “Le Chant du Monde.” When he returned from war in 1917, the violent memories of the battle at Verdun followed him. “I came out of that darkness, finally, through tapestry. A work of art is an assemblage of scars,” he explained, “working in a group like that is always therapeutic.” That sense of teamwork made Lurçat feel as if he were creating not just a work of art, but a community to live in.

We might mention that his studio wasn’t too shabby, either. Whereas Picasso had to slum it in Montmartre in his early days at the Bateau-Lavoir, Lurçat lived in the “Villa Seurat”; a stunning Art Deco studio designed by his architect brother in 1924. You can still go visit it during France’s Journées du patrimoine (when the cities open up their most exclusive addresses to the public for a week). You’ll notice his burning sun graces the walls:

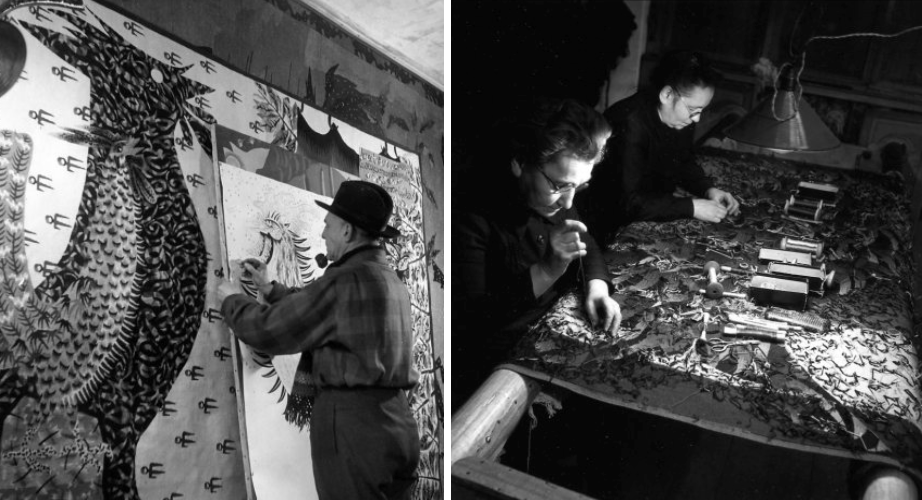

Even more so than his style, what sets Lurçat apart from his contemporaries was his chosen medium. No one was doing tapestry — real, medieval style tapestry — like Lurçat and his team. “There”s nothing more beautiful than creating, say, a giant sun together,” explained the artist, “creating this burning sun that we all already have in common, over us. The tapestry is me, but it’s also all of us.”

Rather than use all of the modern tapestry materials at his fingertips, he decided to do things old school. Instead of pick amongst the 3,000 colours available, he stuck only with the 44 that could’ve existed in the 14th century. He had dozens of specialized helpers, including his (ex) wife, Marthe.

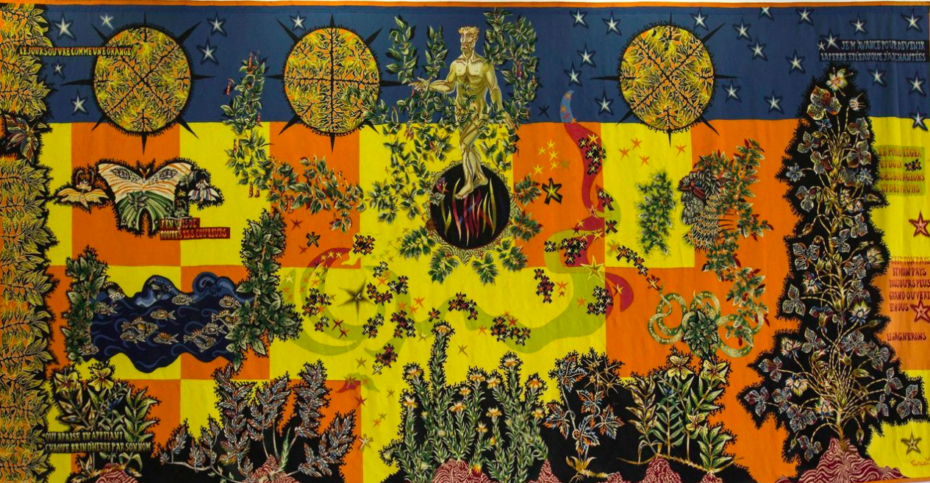

When the artist had seen the medieval Apocalpyse Tapestry in Angers in 1938 — one of the world’s largest at over 100 meters long — he was struck by the vivid depictions of glory and violence, which reminded him of his own experiences in the war. “I was looking at our past, and our tomorrow,” he explained. He never forgot the piece, and 19 years later decided to embark upon a collection of 10 tapestries in homage to Apocalypse, titled “The Song of the World” (Le Chant du Monde). Today, it’s on display at the same museum in Angers as the epic, medieval work:

The Apocalypse Tapestry.©Musée d’Angers

Lurçat’s “Chant du Monde.” ©Musée d’Angers

The piece was a total of 80 metres long, and took over 10 years to create. In fact, it wasn’t even finished when Lurçat died in 1966, and his wife Simone had to take over the project to finish it with their team. “You see everything in this work,” says a representative of the Tapestry Museum of Angers, “The First and Second World Wars. Optimism. Glory. Champagne. Poetry. Death. It’s a testament to the old, and a cautionary tale for future generations.”

You can learn more about visiting the tapestry here.