On a clear day in 1901, at the height of Paris’ most whimsical era of innovation, a curious one-man vessel in the sky could frequently be spotted flying along Parisian boulevards at rooftop level, circumnavigating the Eiffel Tower and sometimes landing at a café for lunch, much to the delight of hat-waving Parisians. The pilot’s full name was Alberto Santos-Dumont, but for many he was simply “the Flying Poet.” The Brazilian aviation pioneer preceded the Wright brothers’ ingenuity with his advances in both lighter-than-air and heavier-than-air craft, and arguably, in demonstrating the first practical airplane.

An heir to his father’s coffee plant empire, Santos-Dumont could’ve easily picked a practical, button-up profession. He settled in Paris to study engineering as a young man, but became entranced by aviation. Today, there’s a street named after him in the Paris’ 15th arrondissement. But back in Brazil, he is a national hero, with countless roads, plazas, schools, monuments, and airports dedicated to him.

His first invention took to the sky on the fourth of July, 1898: a spherical balloon dubbed the “Brazil” that could hold 114.4 lbs. Then came the “America,” a balloon that stayed the skies for 22 hours.

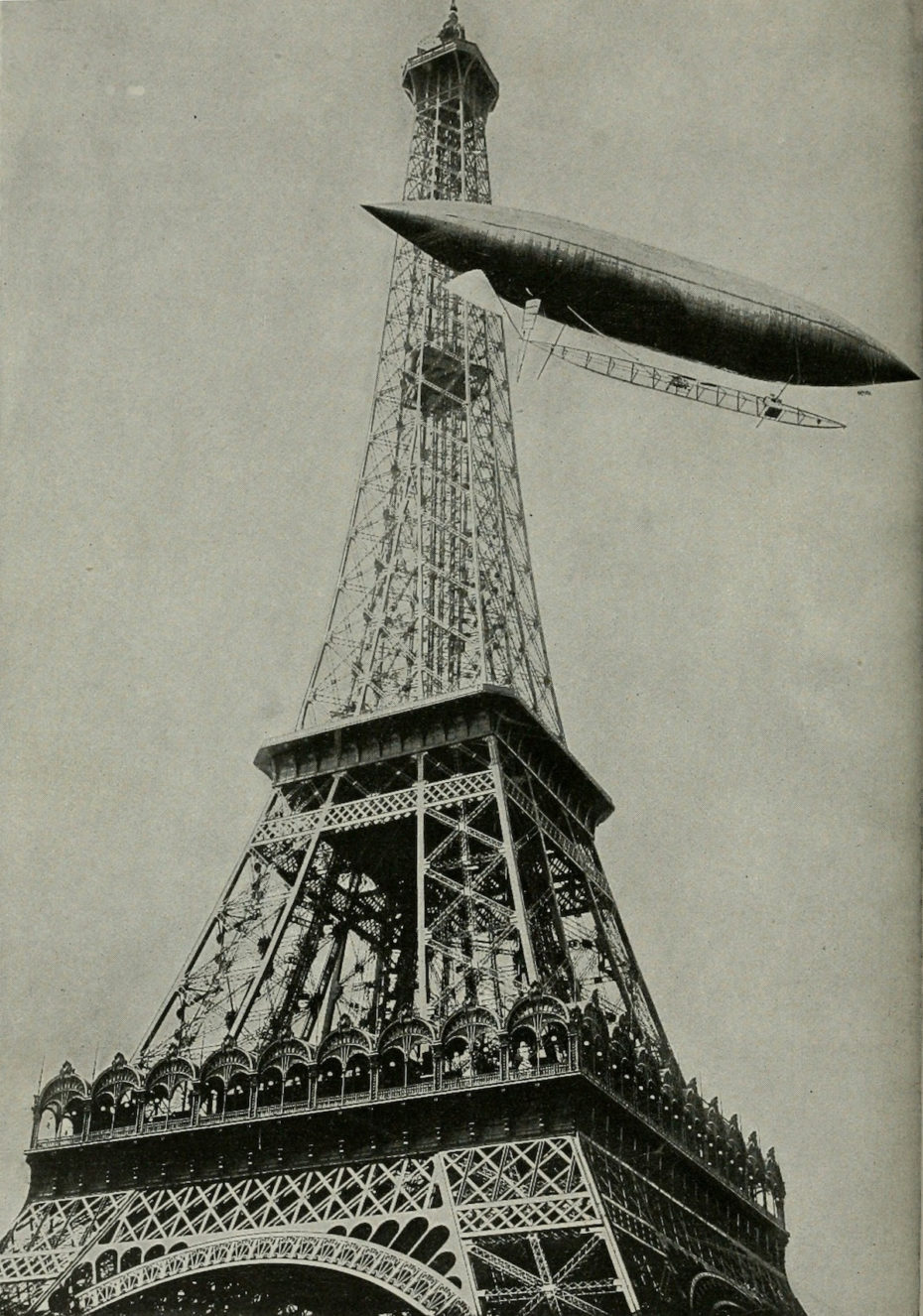

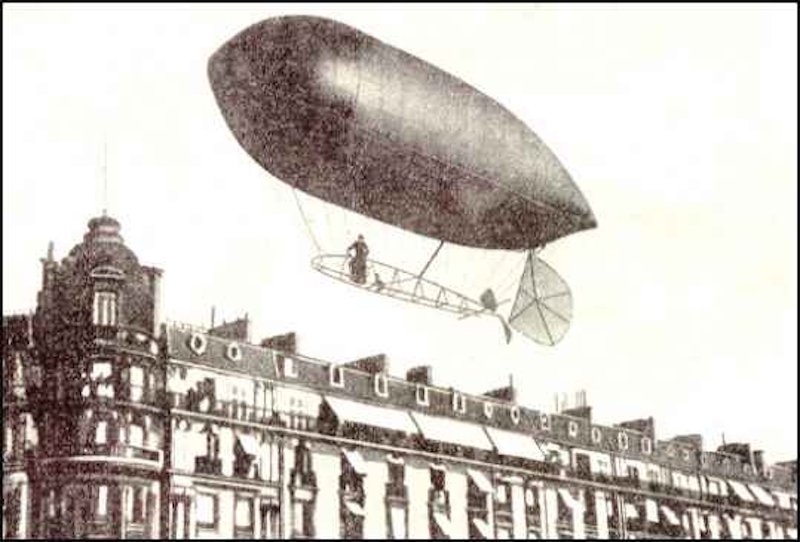

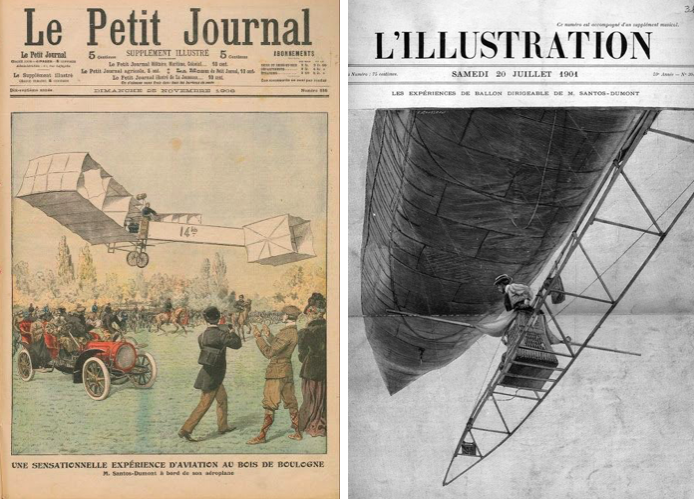

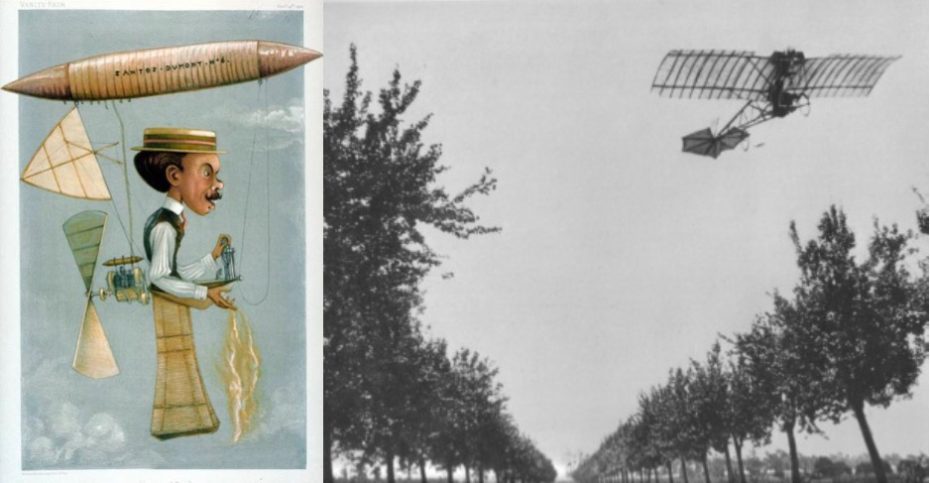

Getting the aircrafts off the ground was one thing — but steering them successfully afterwards? Quite another. It was like “pushing a candle through a brick wall,” he explained. By 1901, his latest, one-man dirigible circumnavigated the Eiffel Tower, and he became an international celebrity overnight. In Paris, they affectionately nicknamed Santos-Dumont le petit Santos and fashionable gentlemen even began copying his style of dress, from his high collared shirts to his signature Panama hat.

The flight was completed in under 30 minutes, and Santos-Dumont was rewarded 100,000 francs for the feat — but he didn’t keep a penny. Instead, he distributed the prize equally amongst the beggars and blue-collar workers of Paris.

Santos-Dumont continued to dazzle with his aircrafts. Especially his heavier-than-air machines like the 14-bis, or the Demoiselle, a high-wing monoplane invented in 1909:

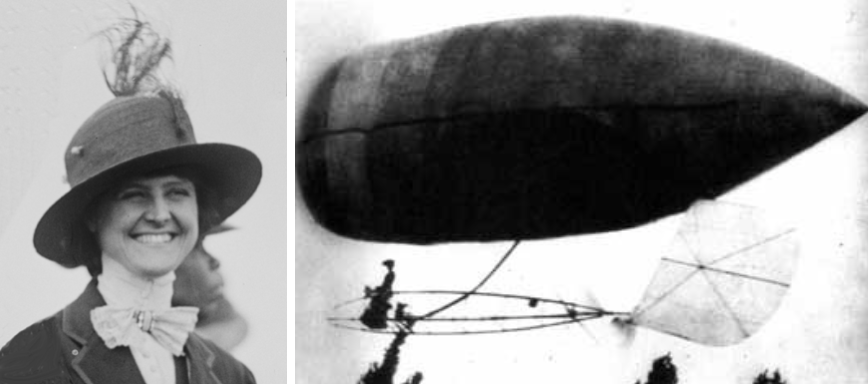

He only let one other person fly his No. 9 airship: Aida de Acosta. The Brazilian was reportedly head-over-heels for the socialite, and with his help she became the first female ever to pilot a plane. She even steered one en route to a polo match in 1903.

Aida de Acosta

Unfortunately, flying the skies didn’t sit well with her parents, who decided to hush-up the event and marry her off. For the rest of his life, Santos-Dumont kept her photo at his desk.

He was a permanent fixture in aeronautical circles up until World War I, but retreated from society due to severe depression. In an attempt to find peace of mind, he moved to the French seaside in 1911, taking up astronomy to calm his nerves. But once again, fate wasn’t kind to Santos-Dumont.

The French police discovered he was using a German-made telescope, and accused him of being a spy. In a panic, he burned his papers and plans, leaving little for historians to understand his original designs today.

Regardless, the legacy he leaves behind continues to soar in his native land, and his home in the Brazilian mountains of Petrépolis is a museum in his honour called “The Encantada.”

PS. Did you ever hear about the 1930s Rooftop Aviation School of Paris?