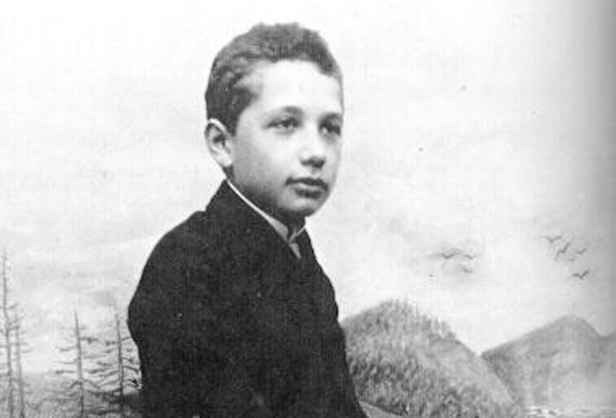

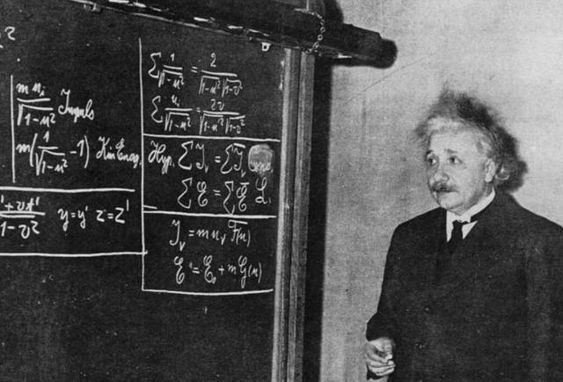

Einstein in 1894.

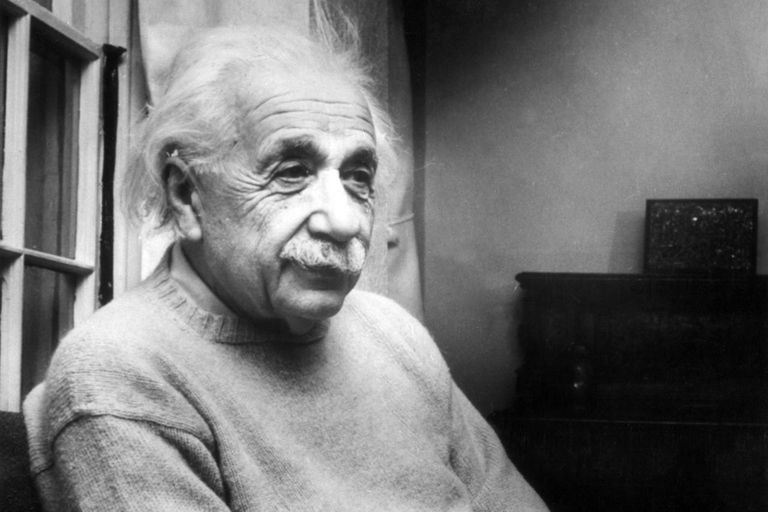

Albert Einstein’s family didn’t think he had a future. He was born in 1879 “with a head shaped like a lopsided medicine ball,” explained journalist Michael Paterniti to Harper’s Magazine over 20 years ago. As we all know, that head became one of the 21st century’s most genius devices. Lesser-known is the fact that it was stolen during Einstein’s autopsy and taken for a 23 year joy ride…

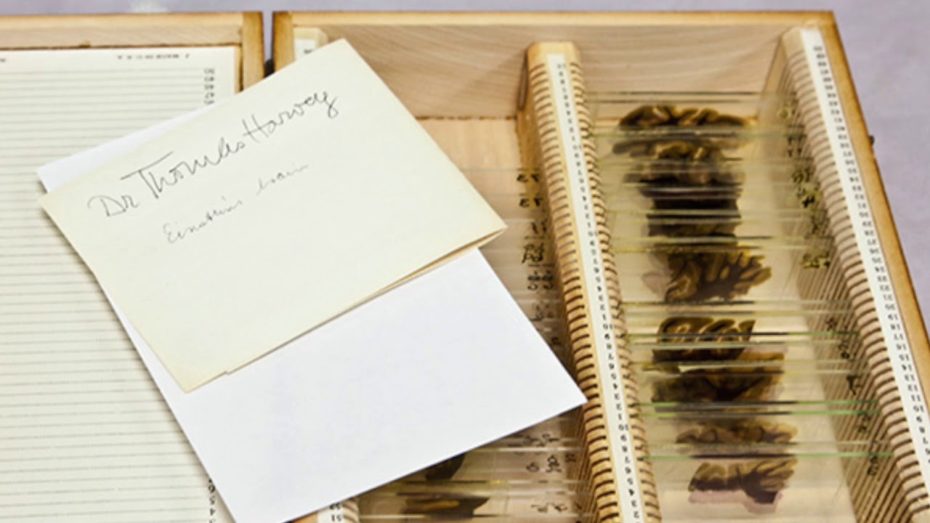

The thief was Thomas Harvey, an on-call pathologist at the Princeton hospital where the father of relativity died in 1955. Einstein had been very clear about wanting to be entirely cremated, but just eight hours after Albert’s death, Harvey snatched his brain and divvied it into 240 pieces over a period of a few months.

Harvey.

For 23 years, he hid the brain from the world in his basement, storing it in beer coolers, cookie jars and Tupperware containers. “What he didn’t count on, however,” said Paterneti, “was that with this one act his whole world would go haywire.”

Einstein’s family were initially furious when they found out. His son, Hans Albert, eventually gave Harvey a reluctant blessing to keep the brain — but only for medical study. And the research just didn’t come in. Years went by. Decades. The U.S. army tried to convince Harvey to give them the brain, thinking it could help them one-up Russia, but to no avail.

Instead, it sat pickled in Mason Jars in Wichita, Kansas. Writer William Burroughs, a friend of Harvey, would brag about driving down south to “have a drink with Einstein” on his pal’s porch. Sometimes Harvey would even shave off slices of it with a kitchen knife and mail them to persons requesting a piece. A 1994 BBC documentary led by Japanese professor Kenji Sugimoto shows Harvey casually slicing off a piece of the brain on a cheeseboard for a visitor to take home as a souvenir.

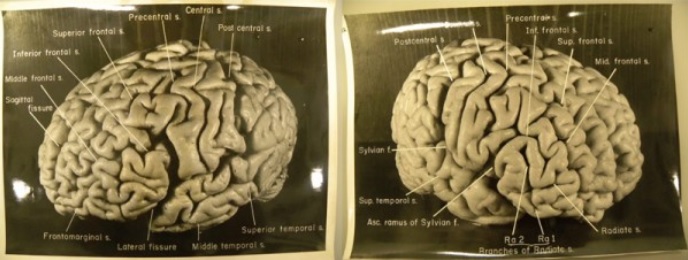

The big game changer was when journalist Steven Levy finagled a visit in 1978. It was “a conch shell-shaped mass of wrinkly material,” he wrote about the brain in a piece for the New Jersey Monthly that shocked the public. “A fist-sized chunk of greyish, lined substance, the apparent consistency of sponge. And in a separate pouch, a mass of pinkish-white strings resembling bloated dental floss.” Other portions of it were preserved in a resin-like material:

© Getty

Harvey wasn’t a neuroscientist — and he was in over his head from the get-go. He knew he would need serious help to unlock the secrets of the brain, and initially he’d partnered up with the late Einstein’s friend, neuropathologist Harry Zimmerman. But Zimmerman just quietly fell off the face of the Earth.

The publication of Levy’s article jump-started a number of studies in ‘80s and ‘90s, but their findings didn’t boast much to write home about. Sure, there were some differences (i.e. an extra ridge on his mid-frontal lobe), but nothing that conclusively revealed itself as the holy grail for decoding his genius.

The thing is, the eyes see what they want to see. “It’s confirmation bias,” Dr. Terrance Hines told NPR in 2014, “If you really want to find something, if you look for it long enough, you will…like seeing faces or shapes in clouds. Those shapes really aren’t in the clouds. They’re in your mind.” Perhaps that’s why Harvey grew so reclusive when it came to the studies on the brain; he just couldn’t bear to let go of the fantasy.

“His [Einstein’s] theories predicted the origin, nature, and destiny of the universe,” explained Paterneti, “he toppled Newton and nearly three hundred years of science.”

Harvey in later years with “the brain.” ©Gizmodo

Harvey passed away in 2004, and today, you can see the brain for yourself at the Mütter Medical Museum in Pennsylvania. Oh, and did we mention Einstein’s eyes were also stolen, and remain hidden in a safe box in New York? But that’s another tale entirely…