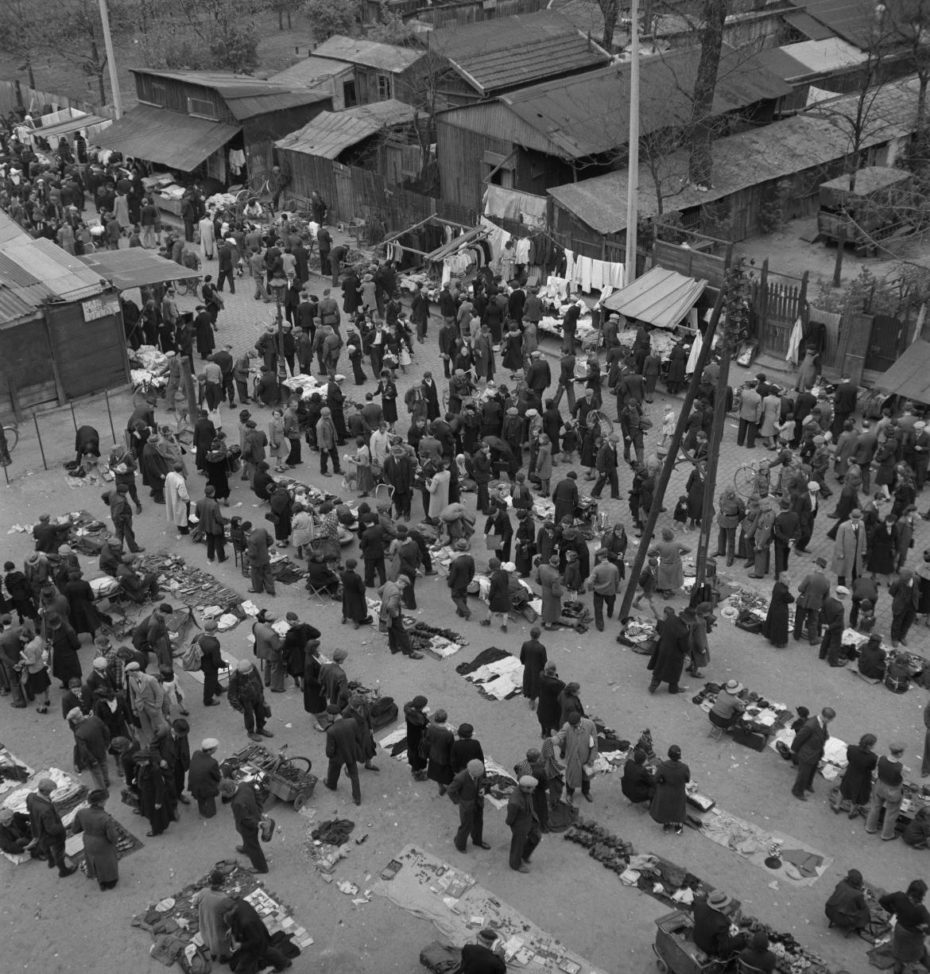

In 1941, Paris was under the heel of the Hitler’s army during the occupation of World War II. The photographer behind the lens is André Zucca, a French photojournalist and Nazi collaborator. It was the year he’d been contracted by the Germans to work as a correspondent for Signal, a propaganda magazine of the German Wehrmacht. His assignment: to support a positive, seemingly-carefree image of the life in occupied France.

Capturing the weekend scenes of the Marché aux Puces de St-Ouen, Zucca delivers a portrait of Paris’ iconic flea market not so different to the one today .

(Minus the German officers browsing for antiques ↑).

That’s the thing about the Paris flea market. It’s a place unlike any other, frozen in time. It’s the same curious bric-a-brac laid out on the cobblestones and the same faces trading timeworn objects. Even the streets and the make-shift infrastructure of the market appear unchanged.

(Side note: interesting ladies’ footwear ↑)

Our wartime flea market guide began his career as a photographer after he was wounded in WWI during his service in the French army, for which he received the Croix de Guerre honor. It’s disputed whether or not Zucca’s work during WWII for the Germans had anything to do with him actually sympathising with the ideals of Nazism– or if he was just betting on what he thought was the winning side.

Of course, he ultimately chose the wrong army to work for. Following the liberation of Paris, he was put on trial and permanently stripped of his journalistic privileges. He got off lightly compared to other Nazi collaborators thanks to the credentials of a French resistance member who spoke out on his behalf. With his journalism career finished, Zucca changed his name to André Piernic and moved to northern France, where he opened a small photo boutique in the town of Dreux, and did portrait work for weddings and communions. He died in 1973.

I found Zucca’s photographs buried in the archives of Municipal Library of Paris. His photo collections were purchased by the Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris in 1986, consisting primarily of his work on Paris taken during World War II. He is better known for his colour photographs, as he was one of the few photographers in occupied-Europe with access to Agfacolor film, a rare and expensive piece of color film at the time, thanks to his relationship with the Germans.

Ten years ago, a major French publishing house worked with the city of Paris to organize an exhibition of Zucca’s wartime photographs. News of the exhibition was controversial from the start. Both organisers and even Zucca’s relatives were accused of minimising André’s collaboration with the Nazis. The photographer had been so successful at portraying a seemingly-carefree Paris during wartime, the deputy mayor of Paris went as far as to call the exhibition “indecent” and “revisionist”. In the end, the city had the exhibition taken down.

What to do with the beautiful work of a corrupted artist? Leave it buried in the archives? I couldn’t.