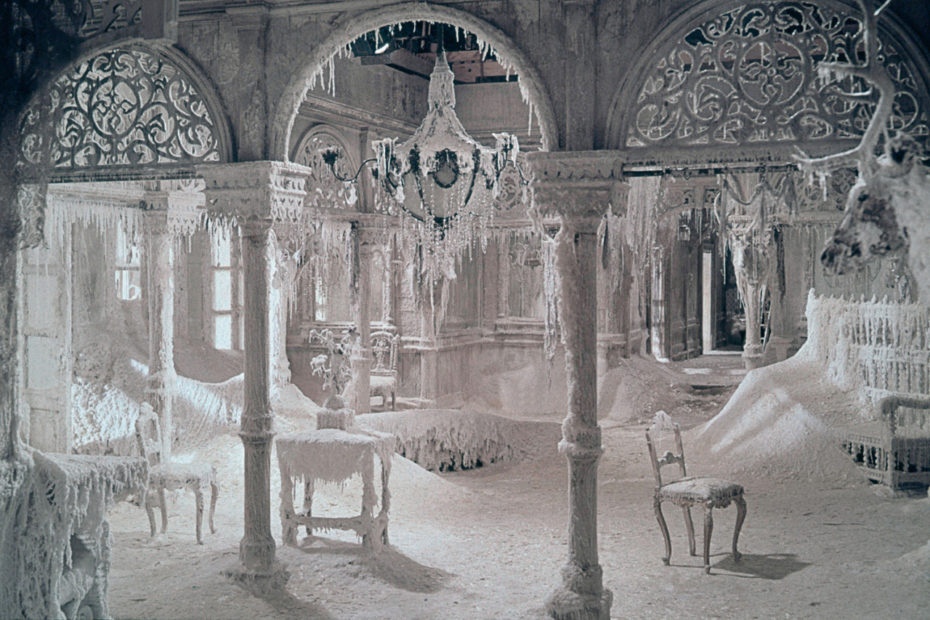

I‘ll never forget the first time I watched Dr. Zhivago and the chills it sent down my spine as Yuri and Lara walked into their abandoned ice palace; the winter dacha of the Varykino estate. I haven’t been to Russia yet, but I dream of it; of boarding the Trans-Siberian Railway, travelling deep into mother Russia, blanketed in snow, and somehow stumbling upon an old abandoned dacha waiting for me in the forest. Until that happens, I’ve been doing my digging, and stumbled upon a few things almost as good…

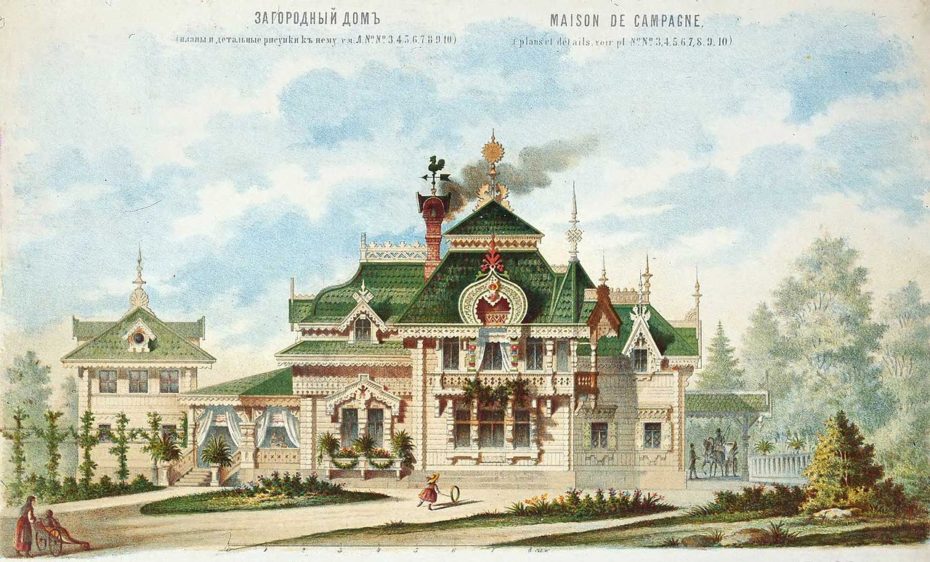

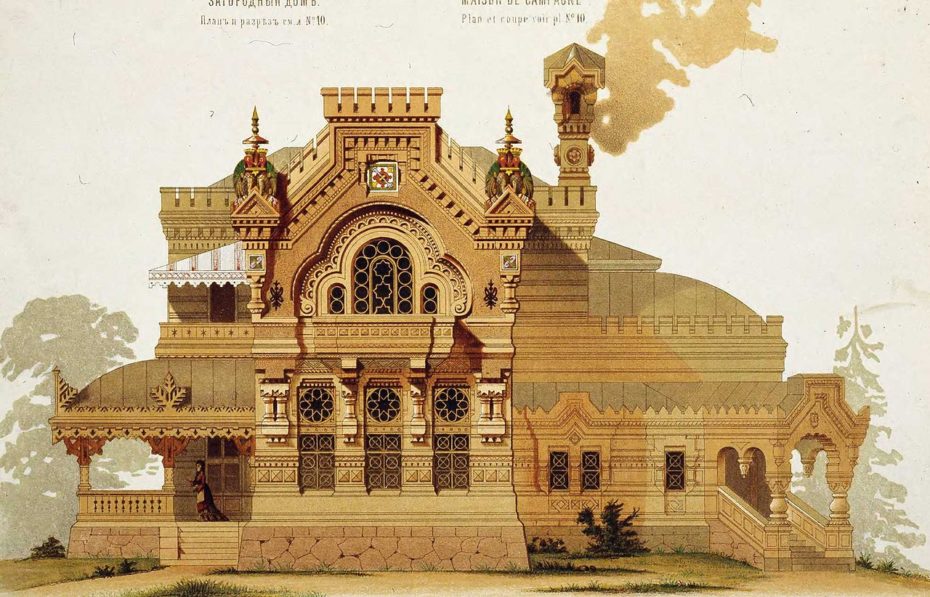

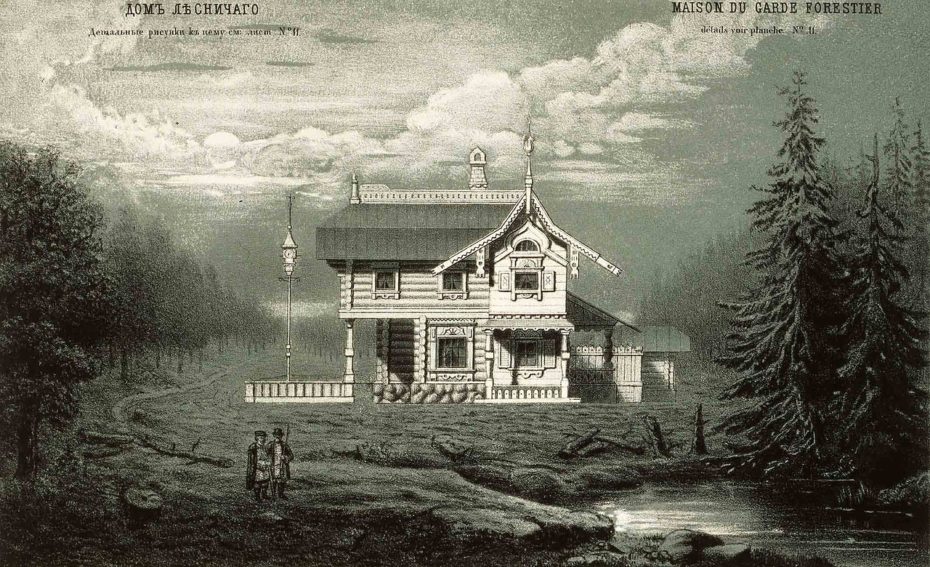

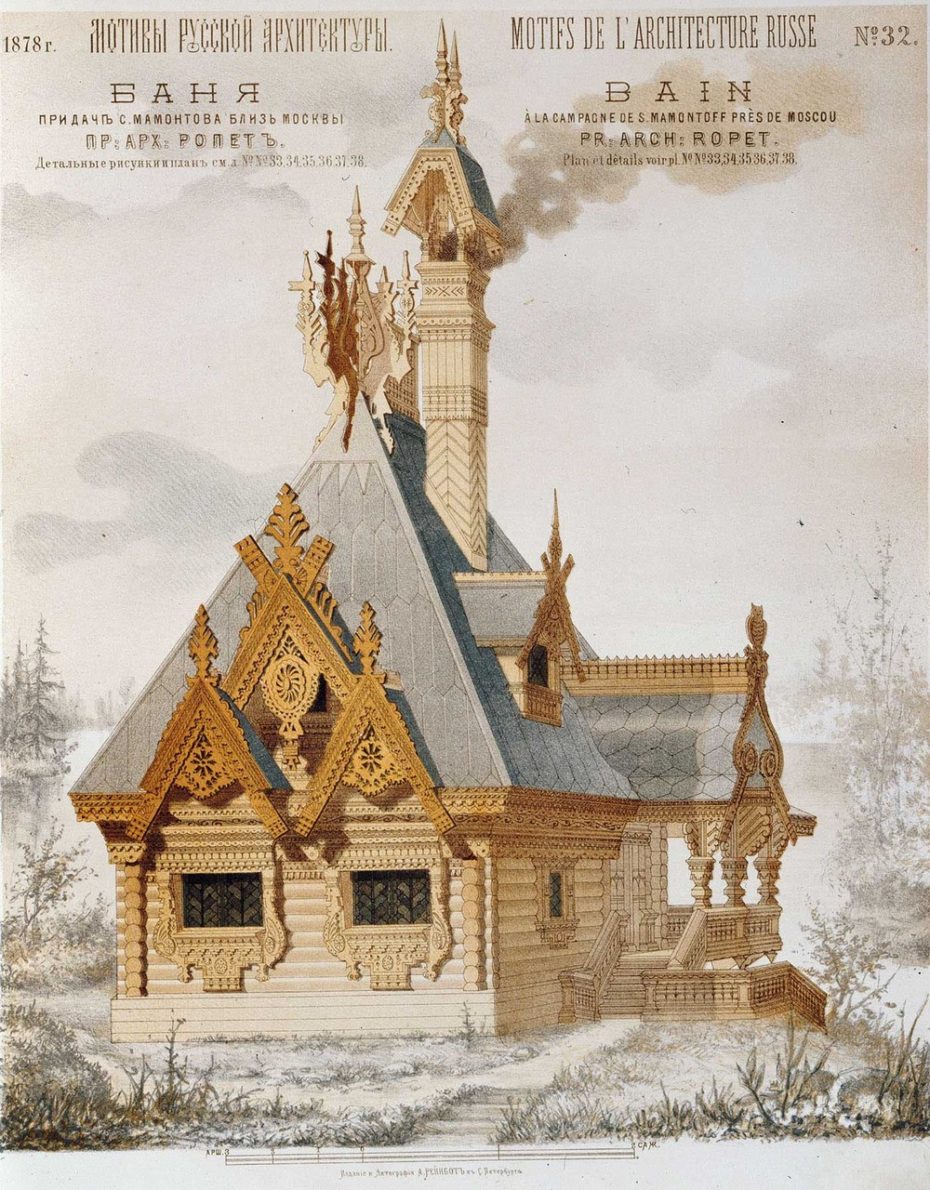

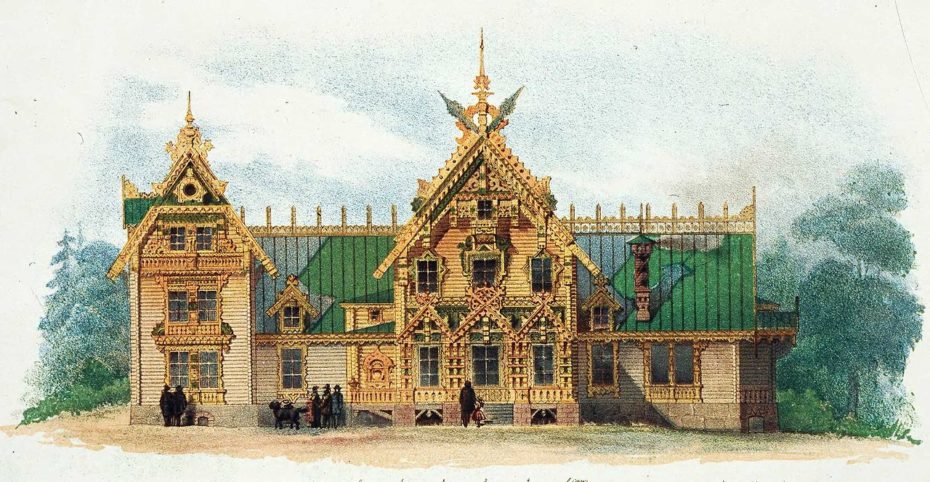

First, these beautiful and intricate drafts and sketches from “The Motives of Russian Architecture“, a famous magazine published between 1873 to 1880, containing works of architects and followers of the traditional “Russian style. It was essentially the bible of Russian architecture. I don’t have much more information on the sketches than that (it’s all in Russian after all), so I’ll let the art do most of the talking…

What is there to know about the dacha? In archaic Russian, the word dacha means something given. The first dachas in Russia began to appear during the 17th century and originated as small country estates or ‘second homes’, given as a gift by the tsar. Over generations, they’ve evolved from the fairytale wooden palaces of Tsarist Russia to more modern country retreats, but the tradition of the dacha has survived through revolution and Soviet destruction.

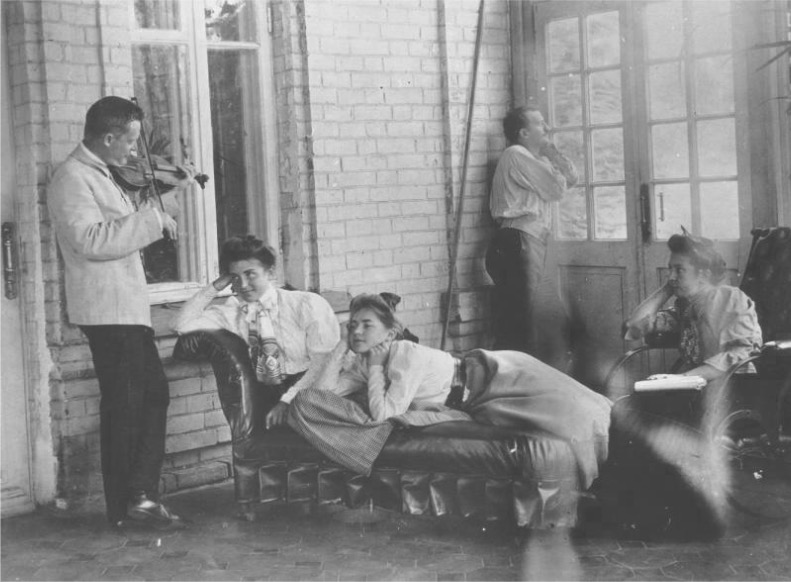

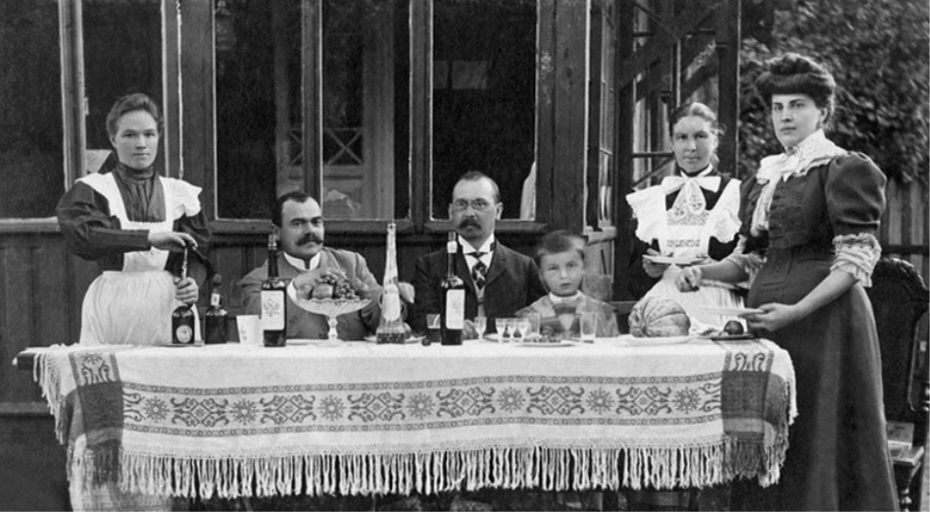

The dacha is as engrained in Russian culture as their vodka, ushanka-hats and bowls of borscht. Their cherished rural retreats are the cause of colossal traffic jams every Friday evening as city-dwellers pile in their cars, headed for the country. In the summer, they decamp en masse, leaving an empty metropolis behind to tend to their gardens, host tea parties on the veranda and enjoy the peace of their dacha. It’s estimated that almost a quarter of families living in large Russian cities have dachas.

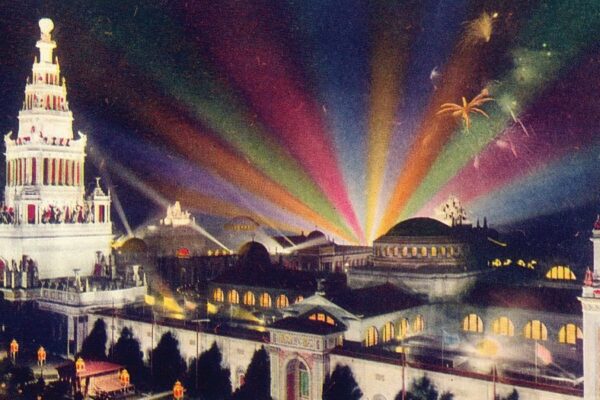

During the Age of Enlightenment, Russian aristocracy built elaborate palatial dachas for social and cultural gatherings, which were usually accompanied by masquerade balls and fireworks displays. With the Industrial Revolution came the railways, a rapid growth in the urban population, and the rise of wealthy middle class urban residents building summer retreats to escape the heavily polluted cities.

After the Russian Revolution, most dachas were nationalised, branded as “bourgeois” and confiscated by the state, some given to the elite of the Communist Party and others converted into vacation homes for factory workers. The more luxurious dachas were reserved for Soviet leaders, like Joseph Stalin‘s numnerous estates throughout the countryside. Strict limitations were imposed of course on any citizen actually owning their own second home, especially one of that showed any sign of personal wealth.

Gardening was always an important aspect of the dacha, particularly when home farming became a lifeline during the failure of the Soviet agricultural program, leaving the country with a serious shortage of fresh produce.

In the 90s, when Russians were finally allowed to own property again, the rich “New Russians” began building bigger and louder country homes that looked more like garish concrete mansions than the traditional wooden houses of the magic Russian folk tales.

I can’t quite answer how many of the original historic Russian dachas still exist– wood not being the most durable of materials– but I did try to find some. One Russian blog found a collection of houses built in the early 1900s in the Kostroma region (picture above).

I came across more dachas in ruins than I would have liked. This one (pictured above) on the Volga River near the town of Tutaev is known as Sorokin’s dacha. It was built in 1868 and once had its own manicured park with a pond, fountains and pavilions.

In Soviet times, the building housed a rest home, according to Russian Trek, and later became a children’s summer camp for a spell after WWII before being abandoned and left to ruin. I can’t imagine it will be standing for much longer. The photos were taken by this LiveJournal site in 2017 (which is packed with photography of old world Russian architecture).

Pinterest had a few examples of semi-restored dachas to show me, which is encouraging, but wasn’t very reliable for answering to their location.

Interestingly, I did learn that there are a number of dachas to be found outside of Russia. They started appearing in regions of North America where a high concentrations of Russian and Ukrainian immigrants settled and built dachas in rural areas to recreate the best part of their lives back in the USSR. Traditional cottages have been spotted in upstate New York and I found this example all the way in Inverness, California.

In my research, I also managed to identify the location of a stunning dacha I’d often seen photographs of, which happens to be located in Shropshire, England of all places. It’s one of the estate follies of Walcot Hall (which has a number of stunning little cottages for rent, but unfortunately not the dacha).

I think I might have just about satiated my appetite for Russian dachas for the day. Perhaps all there is left to do now is book a ticket on the Trans Siberian Railway (there’s a normal train and a the fancy one). And while Russia might be the current topic of a political media frenzy, I just want to dream of my dacha– and watch Dr. Zhivago one more time.