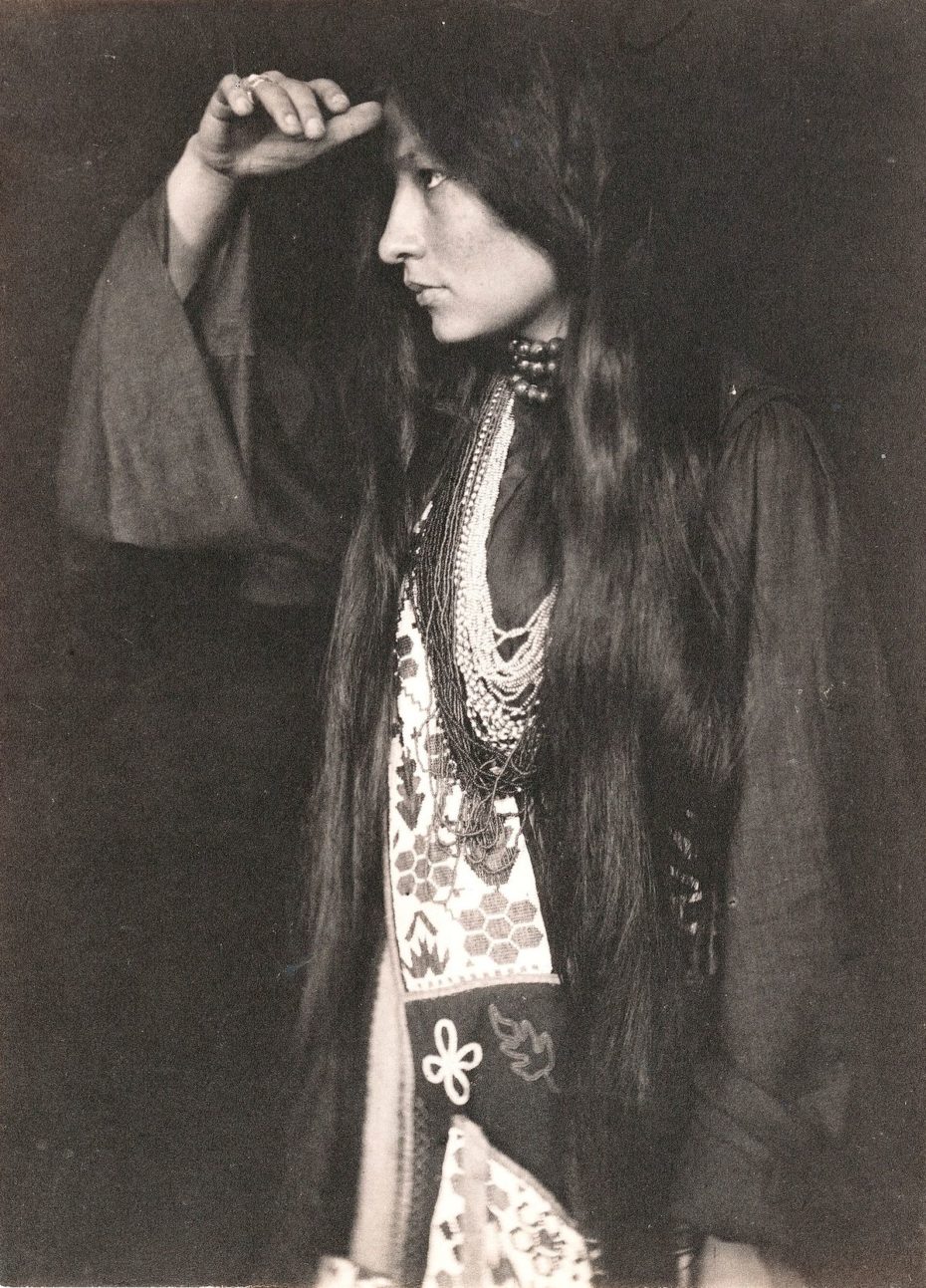

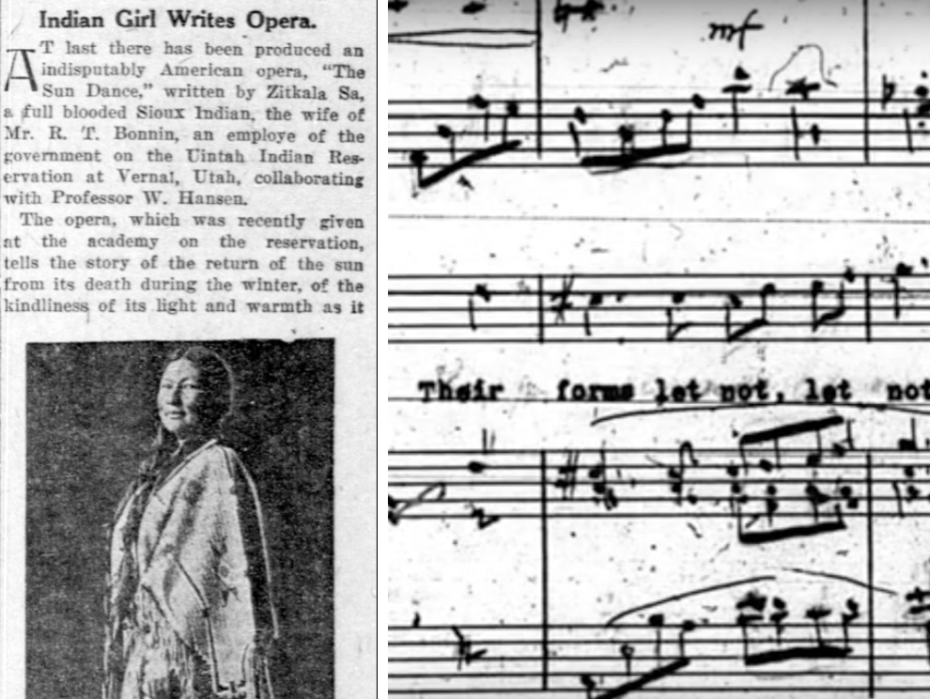

Zitkála-Šá was a woman divided. Torn between her Sioux and caucasian roots, she constantly battled with her own sense of identity. But rather than succumb to that division, she used it as a tool for some seriously creative activism. To this day, one of her greatest feats remains unparalleled: the creation of “The Sun Dance Opera,” a politically-charged musical about the glory of her Sioux kin.

She grew up happily on the plains of the Yankton Reservation with her mother; “a wild little girl of seven,” she explains in autobiographical accounts, “Loosely clad in a slip of brown buckskin, and light-footed with a pair of soft moccasins on my feet, I was as free as the wind that blew my hair.”

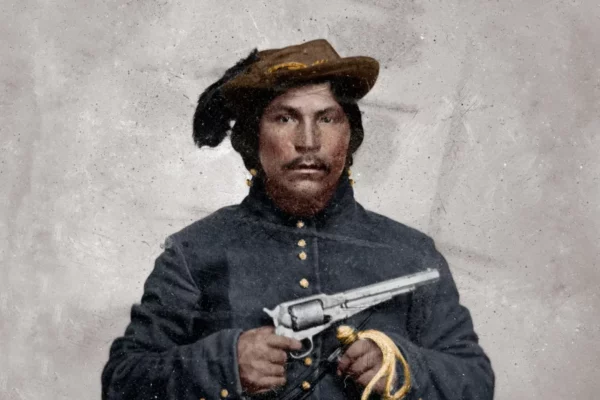

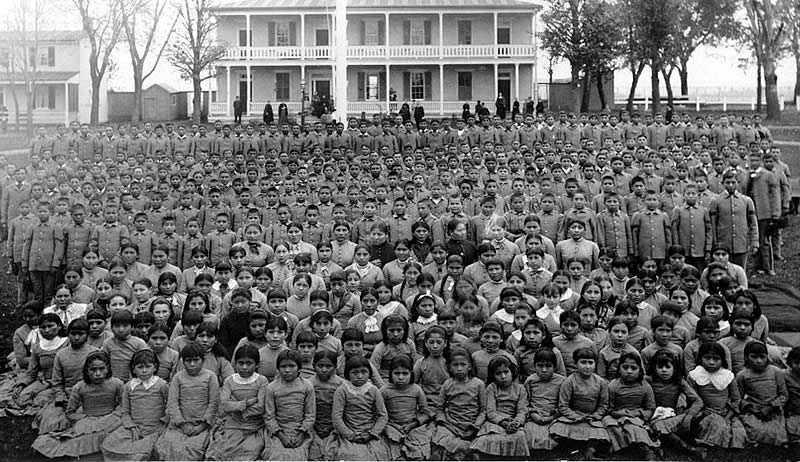

But her father had abandoned their family, and when missionaries came to recruit children for “White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute,” a centre aiming to integrate Native Americans into Quaker society, her mother saw it as a way to give her a leg-up in society. From thereon, they called her by her caucasian birth name: Gertrude Simmons Bonnin.

The assimilation process was a double-edged sword; on the one hand it gave her the means for an education in the arts, and on the other, it taught her to forget her Sioux heritage. When she returned to the Reservation, she didn’t “feel Native American enough”; but when she was with the whites, she still felt like an outcast.

Zitkála was a sharp-tongued writer, and gifted at both piano and violin. She even performed in Paris in 1900), and won a scholarship to the Boston Conservatory of Music. So when she earned a teaching position at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, it was with a staunch Native American rights agenda…

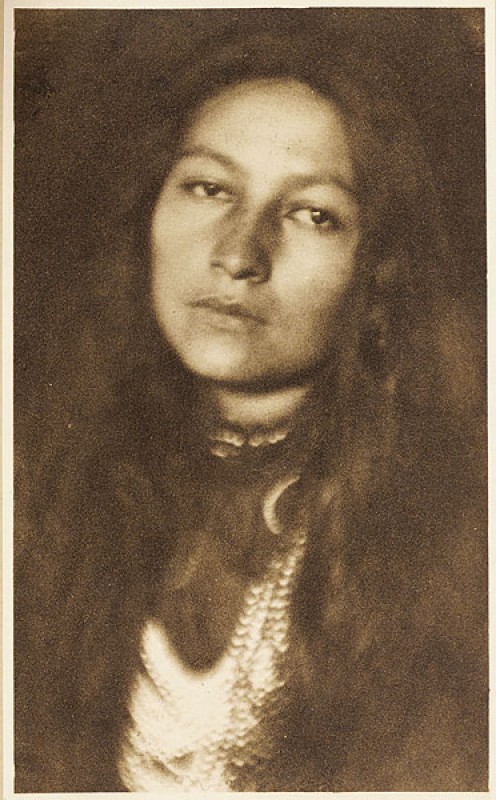

She began penning essays for The Atlantic and Harper’s Weekly in her Siouxpen name, “Red Bird,” to reveal the abusive nature of integration programs. Eventually, it cost her her job. But she took her stories to the printing press with 1901’s Old Indian Legends, and with the eventual production of “The Sun Dance Opera.”

She took Sioux chants that the federal government had banned, and turned them into a libretto and songs. When the opera premiered in Utah 1913, it even employed Native American performers (although the leads were given to white actors) to great critical acclaim. Little by little, she had regained a sense of community and pride in her Native American roots.

The opera was just one aspect of her rich career as an activist (she als0 cofounded the Council of American Indians), but it’s the one that resonates most within her legacy. To this day, no one has brought the beauty of Sioux traditions to the stage quite like her. By the time of her death in 1938, it reached her biggest platform yet: a Broadway run.