She was the model and artist turned war correspondent. He was one of Surrealism’s most iconic figures. Together, Lee Miller and Man Ray lived a fiery romance, set to the backdrop of 1930s Paris. So naturally, we’re keen to relive their story…

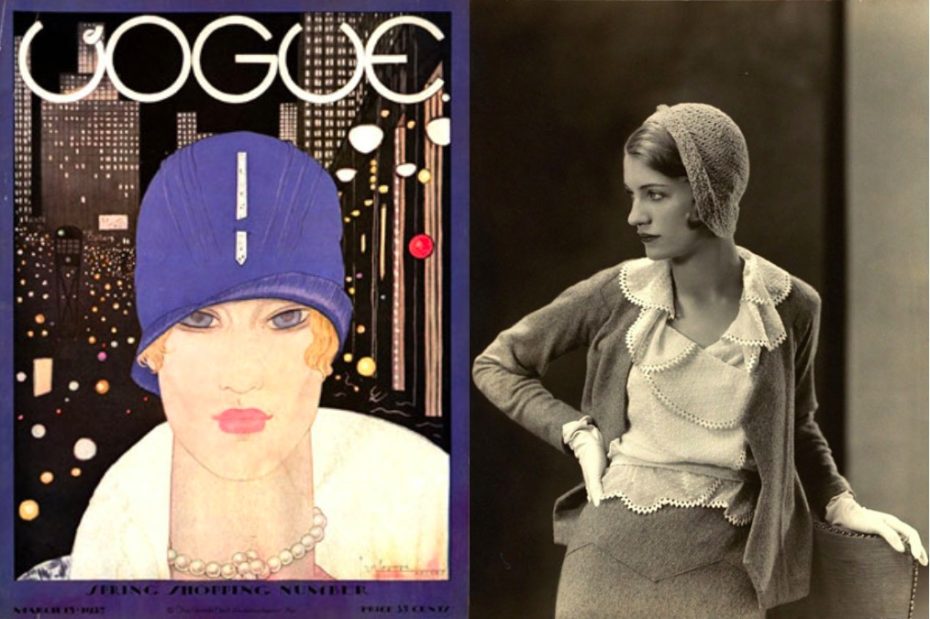

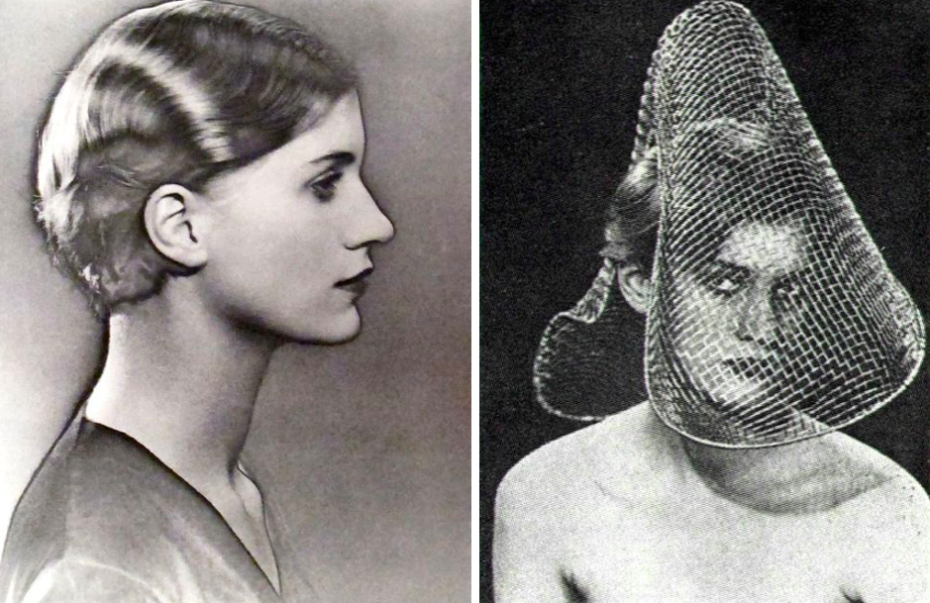

Miller was discovered by Condé Montrose Naste (yes, that Condé Naste) at 19 in New York. She was crossing a street when he plucked her out of traffic and into the pages of Vogue. The Poughkeepsie native’s blonde bob and piercing eyes gave her the look of “a sun-kissed goat boy from the Appian Way,” said Cecil Beaton; she just had that je ne sais quoi, and rose to the top of the game.

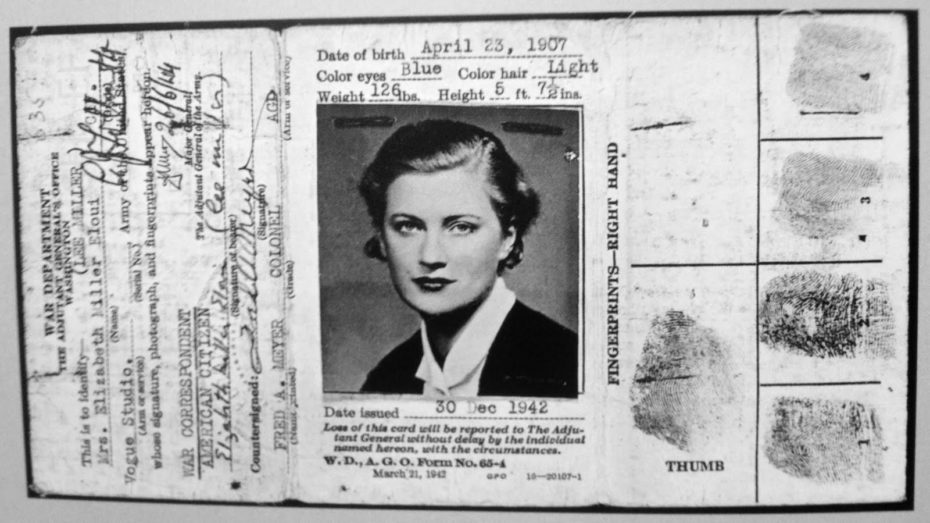

Lee Mille © Condé Nast Archive/Corbis

When she set sail for Paris in 1929, her lovers had to flip a coin to decide who got to see her off. The broken-hearted loser even swooped beside the boat in a biplane to shower her in roses, so you could say she had a powerful effect on her men — but she met her match in Man Ray.

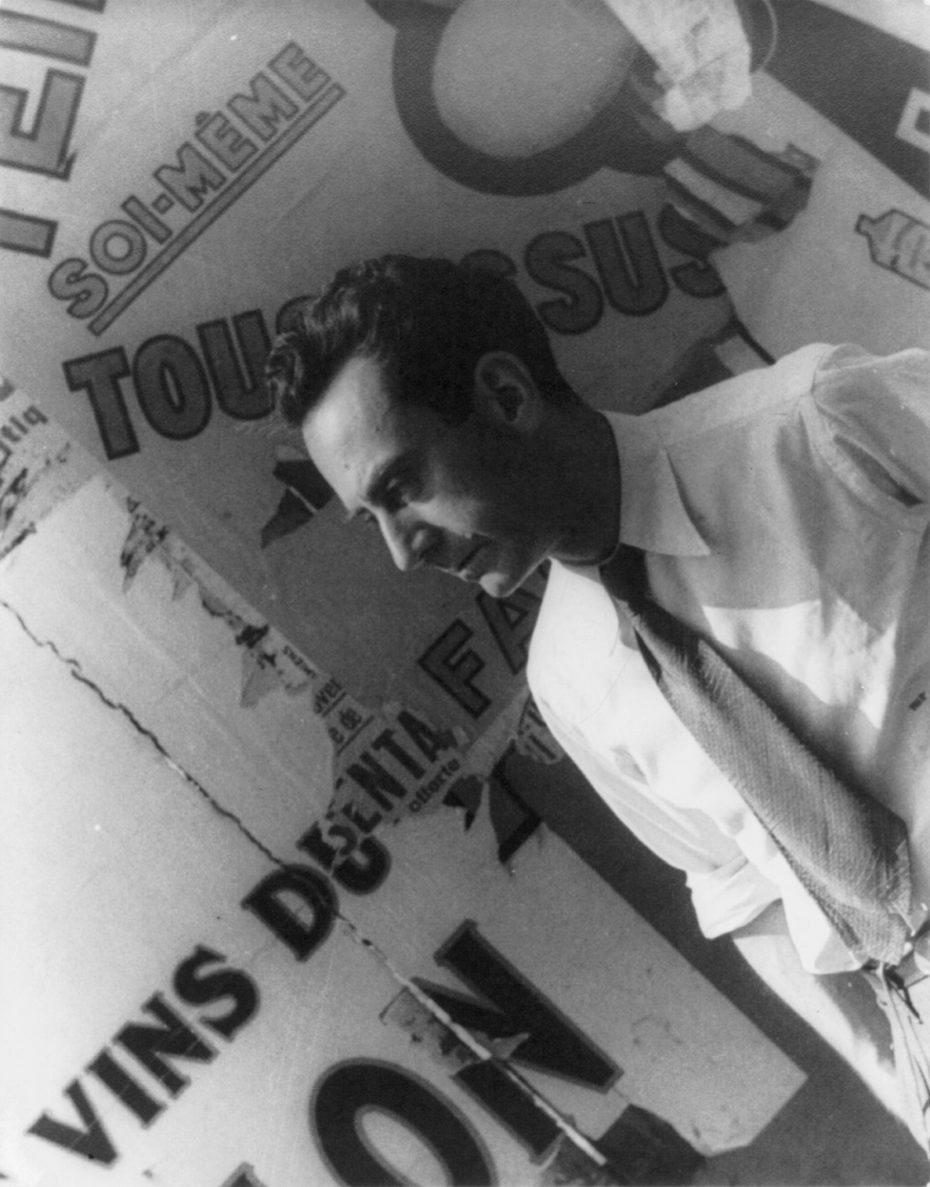

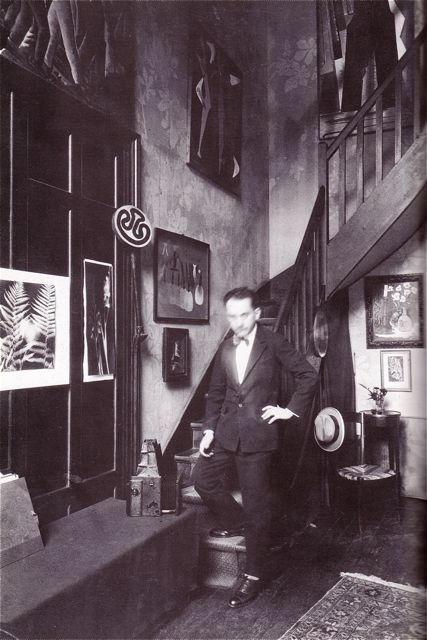

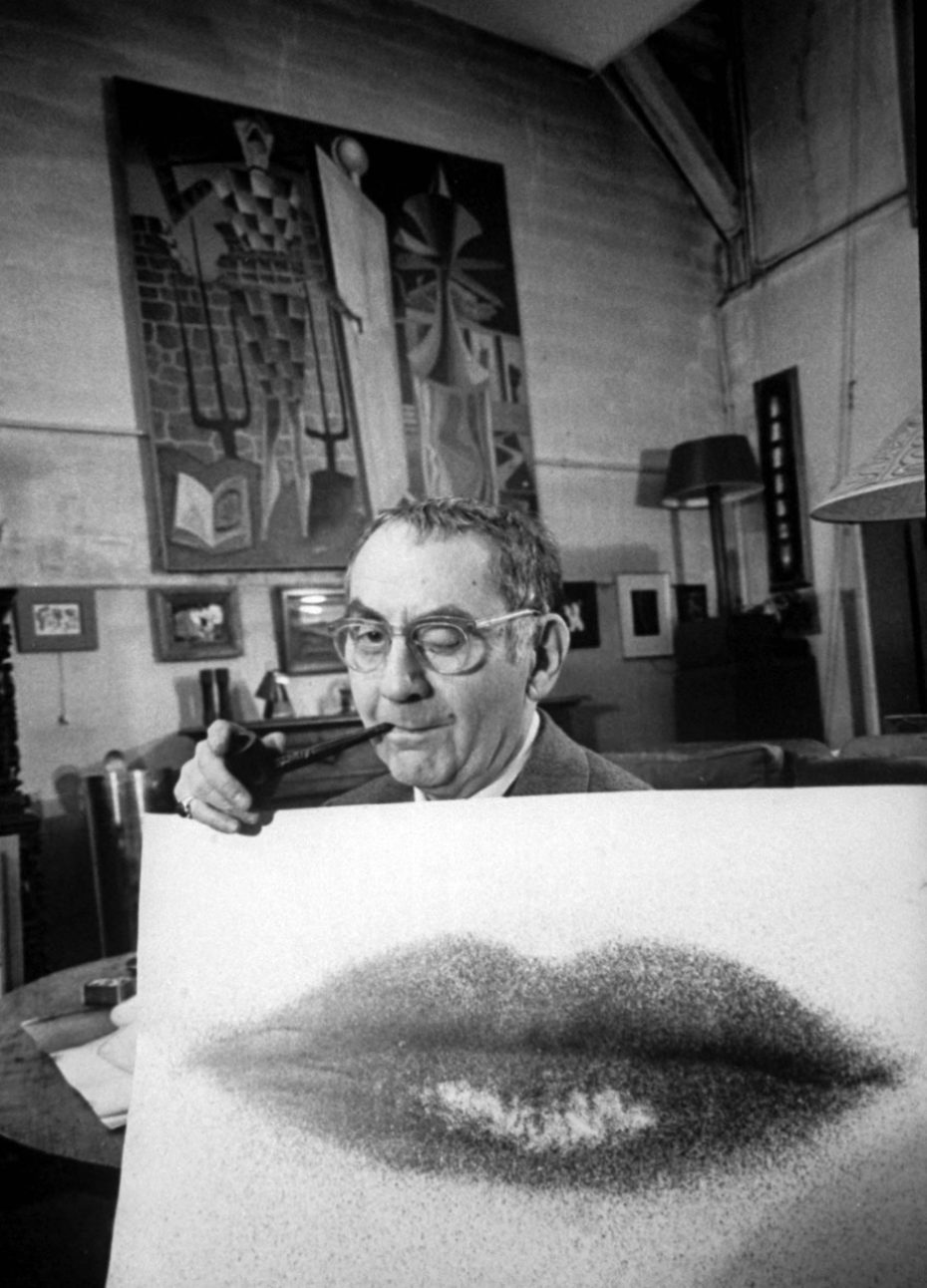

Man Ray in 1934 © Carl Van Vechten Photographs/ Library of Congress

The South Philly-born, Paris ex-pat was a fixture of the French Dada and Surrealist scene, moving in circles with Dali, Cocteau, Marcel Duchamp, and the like. His photography was electrifying, from his portraits of local prostitutes to eerie snapshots of everyday objects.

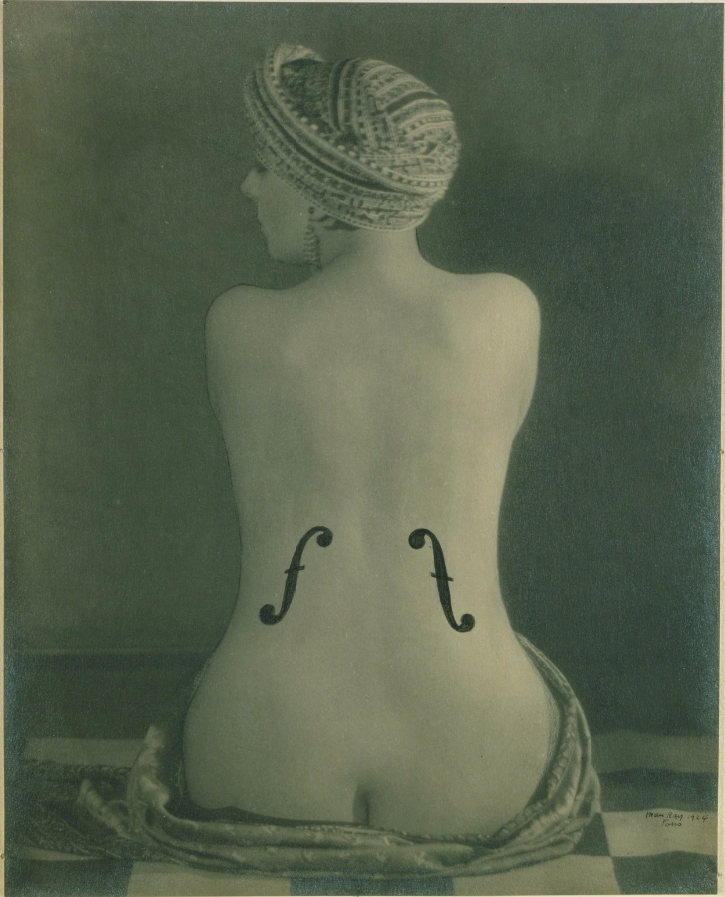

Man Ray’s famous portrait of Kiki de Montparnasse “Le Violon d’Ingres”, 1924

He’d even made a name for himself in fashion photography, and was famous for a kind of irreverent charm. “If he took your hand or touched you,” said Miller, “you felt an almost magnetic heat.” When Miller spotted him at a bar on Paris’ Left Bank, the Bateau Ivre, she was instantly smitten.

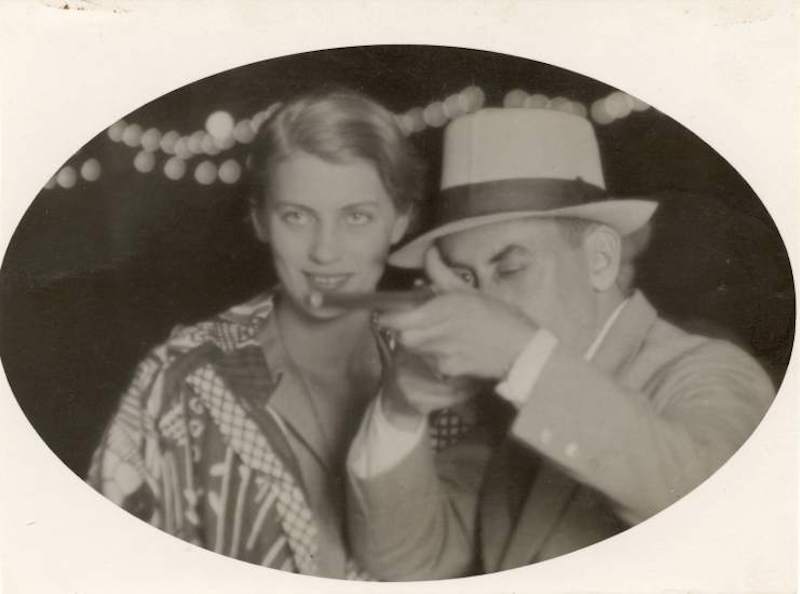

Miller + Ray © Lee Miller Archives

“I was chasing him,” she told a Home Journal interviewer in 1975, “He looked like a bull with an extraordinary torso and very dark eyebrows and dark hair. I said, ‘My name is Lee Miller, and I’m your new student.’ Man said, ‘I don’t have students.’ He was leaving for Biarritz the next day, and I said, ‘So am I.’ I never looked back!”

Miller (far left) and Ray (right) with another muse, Ady Fidelin.

She became his muse, and when Miller started asserting her own talents with her lover it was creative kismet.

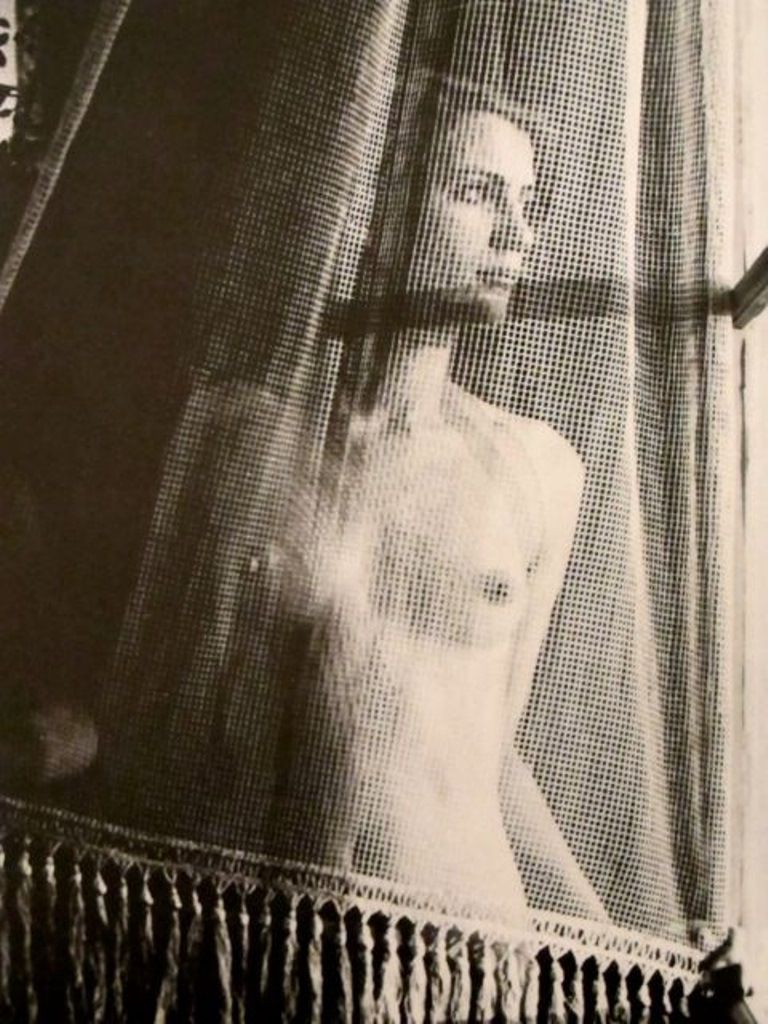

© Lee Miller Portrait, 1930 by Man Ray

Together (although some historians credit Miller completely) they discovered how to solarize photos to give them a ghostly, glowing look:

Lee Miller Archives

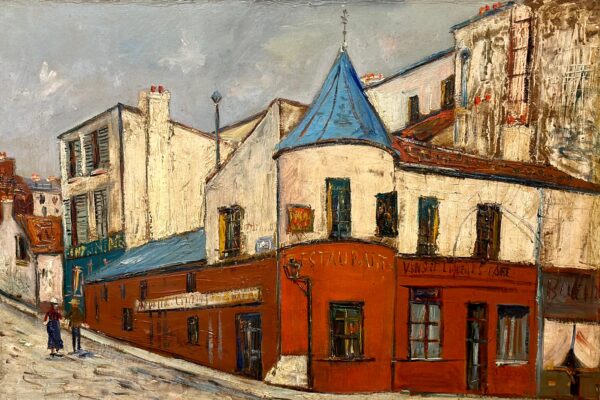

They were one of Paris’ bohemian It-Couples, playing house in Ray’s atelier in Montparnasse. Ray encouraged Miller’s interest in photography, giving her a camera and the confidence she needed to take the streets of Paris and capture its rhythm…

Man Ray’s atelier.

But the more Miller flourished, the more the relationship became strained. “Miller was not necessarily any less gifted than Ray,” explained a 7×7 journalist in 2012, “She was as much caged by her relationship with him as she was stimulated by it.” Ray had been begging her to settle down, and become his wife. She wouldn’t have it.

Miller and Ray

The turning point was in 1932, when Ray found her trying to repurpose negatives that he’d thrown away. In a rage, he threw her out on the street. She retaliated by buying a ticket home to the Big Apple. When the reality of what he’d done sunk in, Ray went into a deep depression. For two years, he worked tirelessly on a painting of his lost love’s lips:

The finished piece was crowned “Les Amoureux — A L’Heure De L’Observatoire” (The Lovers – Observatory Time). “This famous image of Lee lips floating over the Paris observatory against the morning sky, remains one of the most haunting expressions of his nostalgic despair, and the enduring scar that she inflicted on him,” writes one art magazine. A sharp eye can spot the Paris Observatory in the distance (which is still in use to this day).

Miller had taken up permanent residency in Ray’s heart and creative vision. The only way he could break his grieving cycle, he explained, was to create work after work in her honour.

When the agony was more than he could bear, he decided to create a piece that would force him to symbolically crush his love for Miller. Enter the metronome.

“Cut out the eye from the photograph of one who has been loved but is seen no more,” he explained, “Attach the eye…and regulate the weight to suit the tempo desired. Keep going to the limit of endurance. With a hammer well-aimed, try to destroy the whole at a single blow.”

He followed Miller’s gaze, day after day, before smashing it to pieces. Ironically (and with a hefty dash of Ray’s signature black humour) he entitled the piece “Indestructible Object.” (The work we have today is a reproduction.)

Meanwhile, Miller went off to become a remarkable WWII photojournalist, and was the only female photographer given permission to travel independently in the European war zones. She ventured onto battle beaten beaches, and into the Dachau concentration camp. Just hours before Hitler committed suicide, she broke into his apartment and took a bath in his tub.

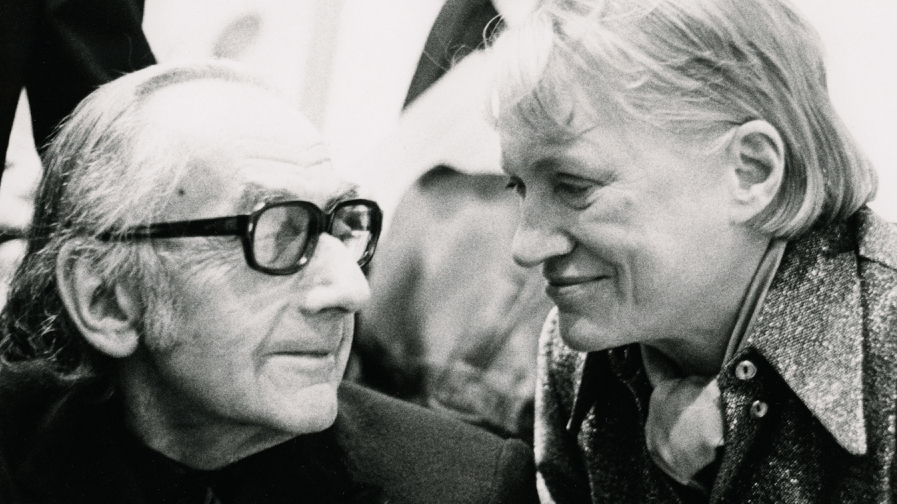

They are pictured together in London in 1975.

Eventually, the two reconciled when they ran into each other at a party. Years had passed, and civility grew into a sincere friendship. They’d found new countries, and new lovers. Still, it was still Miller who pushed a frail Ray in his wheelchair at one of his final exhibits — a mad love that calmed, and stayed the course.