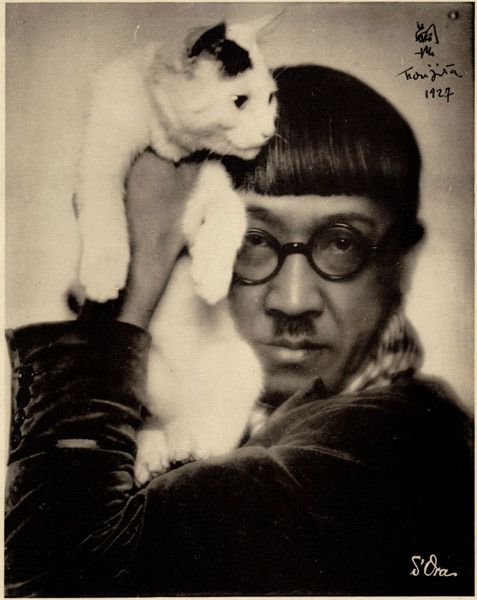

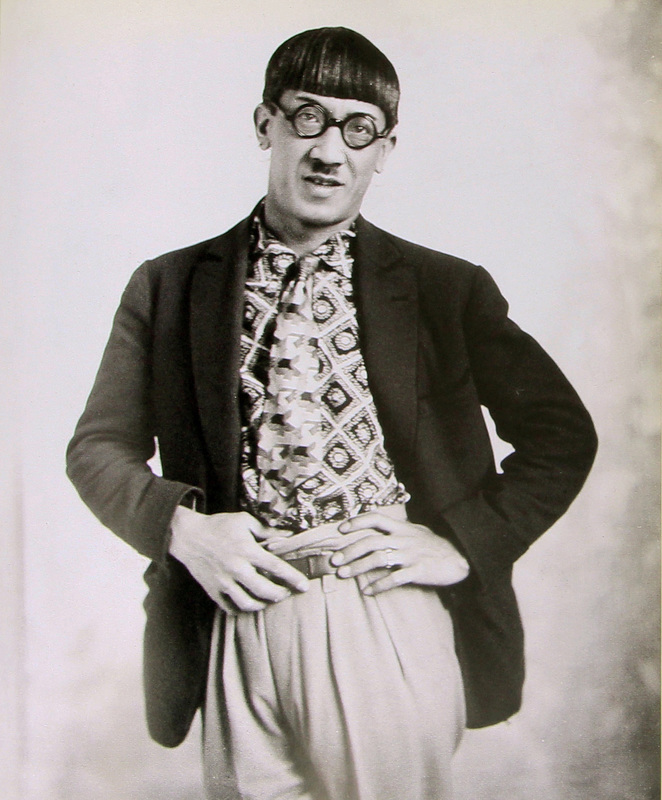

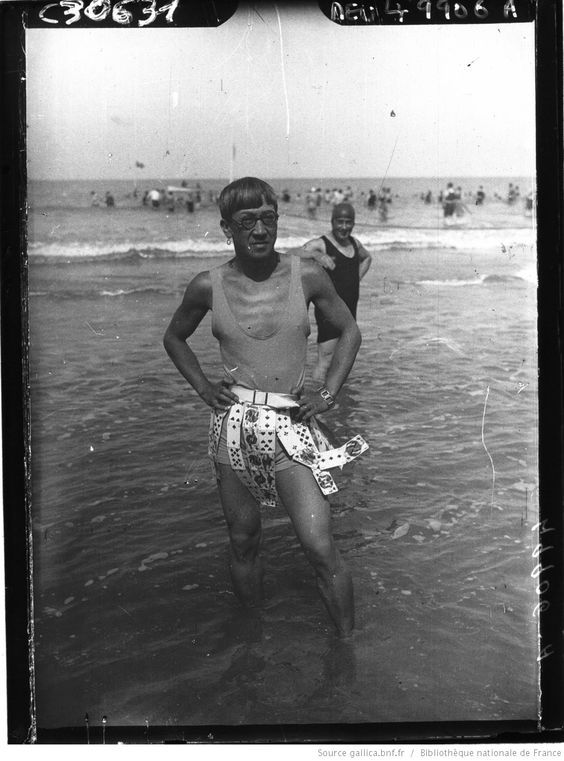

The life of Tsuguharu Foujita reads like a long lost Wes Anderson movie — and looks like one, too. The expat artist arrived in Paris from Japan in the 1920s, and with his prim bowl cut, button-ups, tiny spectacles (and curious passion for cats), his eccentricity made him the crème de la crème of the Montparnasse bohemians. Let us retrace the steps of the man who out-cooled even the Parisians in one of the city’s most colourful periods…

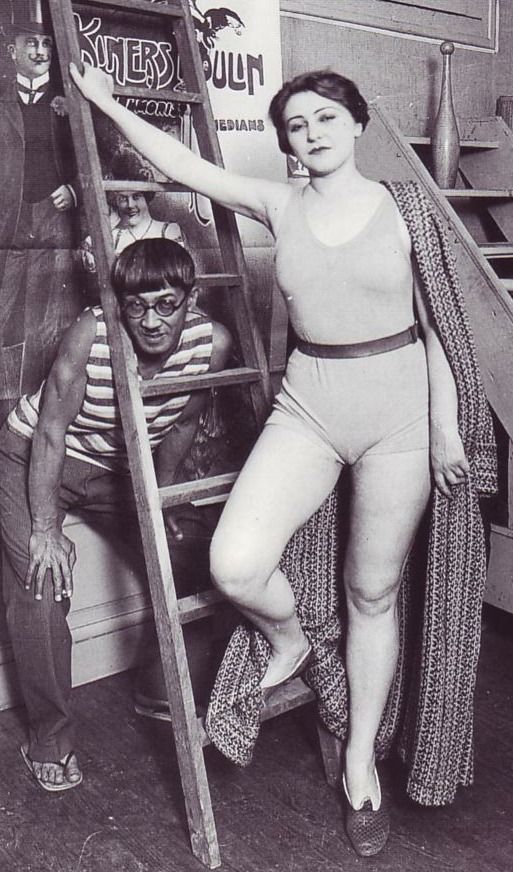

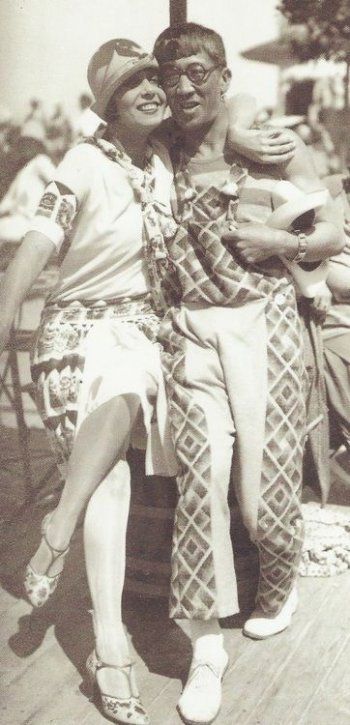

Tsuguharu Foujita & Lucie Badoul (aka Youkie Desnos)

“Based in Paris from 1913 he became Japan’s only painter of international significance at that time,” explained a journalist from Japan Times in 2016. For one, his personal style turned quite a few heads:

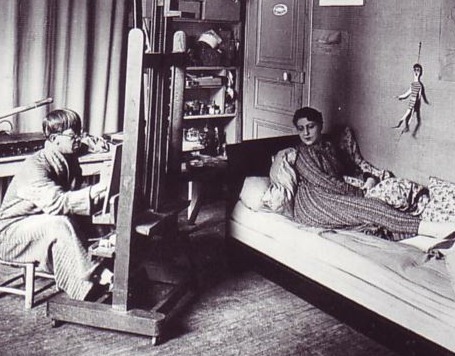

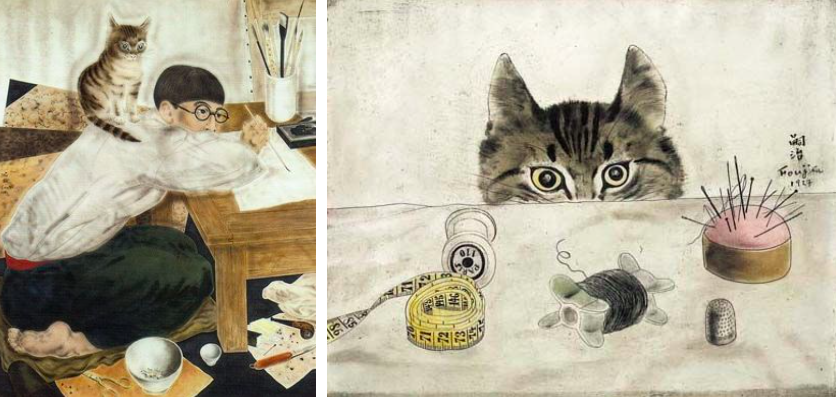

He was a bit of a happy conundrum for the French, combining his knowledge of traditional Japanese painting and French Impressionism to create a minmalist yet whimsical style of painting in his Montparnasse studio at no. 5 rue Delambre. The building still stands today, between a butcher shop and a shoe store.

The courtyard of 5 rue Delambre in the 1920s.

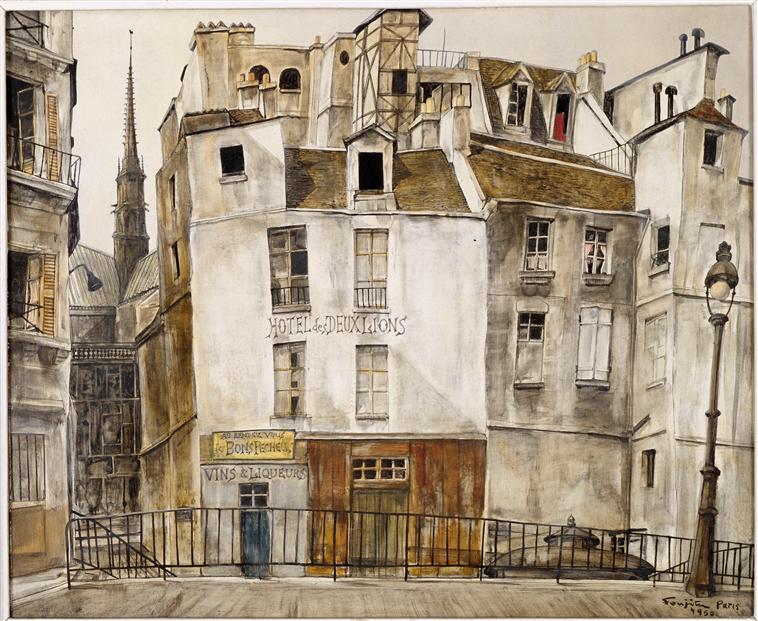

Foujita changed the spelling of his name (originally “Fujita”) to sound a tad more French, and he fell in with all of the greats — Picasso, Modigliani, Matisse, etc. — just a week after arriving, and captured the spirit of Parisian life with a new whimsy:

He earned the nickname “Foufou” (a play on the word foux or “crazy” in French) and became the envy of his peers when he earned enough success to afford installing hot water in his flat. The promise of a steaming bath enticed the greatest models and muses of the day into his studio to pose — he was even able to snatch up Kiki de Montparnasse from Man Ray:

Kiki and Foujita

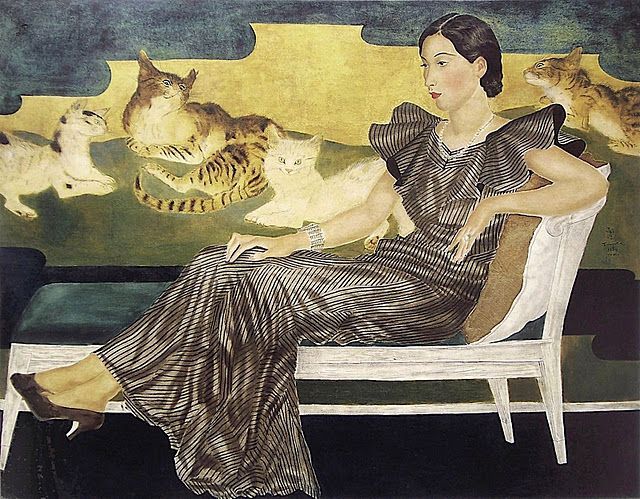

“One of the reasons Foujita was successful in Paris was because he emphasised his nationality, personally and in his art,” said journalist C.B. Liddell in 2006, his painting of Kiki, “Nude with Tapestry,” was hit the perfect note of blending traditional “[Japanese line work] and the muted colors suited to the pale, milky skin then in vogue.” The painting sold for a whopping 8,000 francs back in the day, and runs for upwards of a $1 million today:

Reclining Nude with Toile de Jouy, 1922.

He shuffled between various muses, wooing Modigliani’s go-to gal Fernande Barrey with a blue corsage that he laid on her doorstep in the night, and marrying her a mere 13 days later (although it didn’t last). In 1921, he fell for a Frenchwoman named Lucie, who he nicknamed Youki, or “Rose Snow”:

Youki and Foujita.

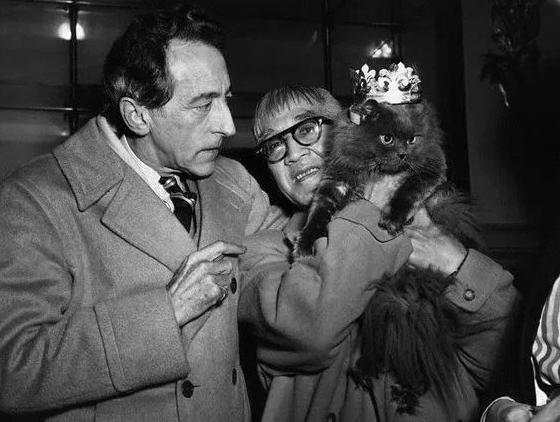

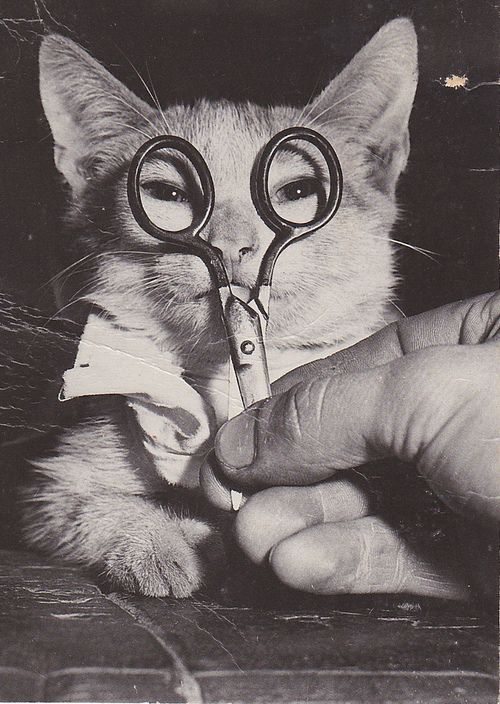

But his greatest loves were indisputably his feline friends — a passion he shared with Jean Cocteau, who went with him to Cat Shows:

Foujita with one of his cats.

They became the subjects of some of his most prized works, and his Book of Cats, a 1930 collection of etched plate cat drawings has become one of the top 500 most expensive and rare books ever sold.

Some art journalists, like Liddell, see Fujita’as obsession with cats as a reflection of a deep seated sense of alienation. By the end of his career, the artist had dazzled Paris’ roaring ’20s crowd, yet he never quite fit in as your archetypical Frenchman. At the same time, he was also seen as too Westernized back home in Japan — even when he began churning out militaristic, propaganda-charged pieces in WWII as his country’s “official war painter.” Cats, however, didn’t care.

Whatever the reason for the fascination, he “landed on his feet as a foreigner in France,” all the while paying homage to his roots while navigating “the backstreets of the Parisian art world” in a way few can boast.

If you happen to be in Paris, there’s a temporary exhibition on his oeuvre at the Maillol Museum. And while we’d love to see Wes have his crack at Foujita’s story, director Kōhei Oguri made a visually stunning biopic on the artist in 2015 (that also delves into Foujita’s move back to Japan in the late ’30s-40s).