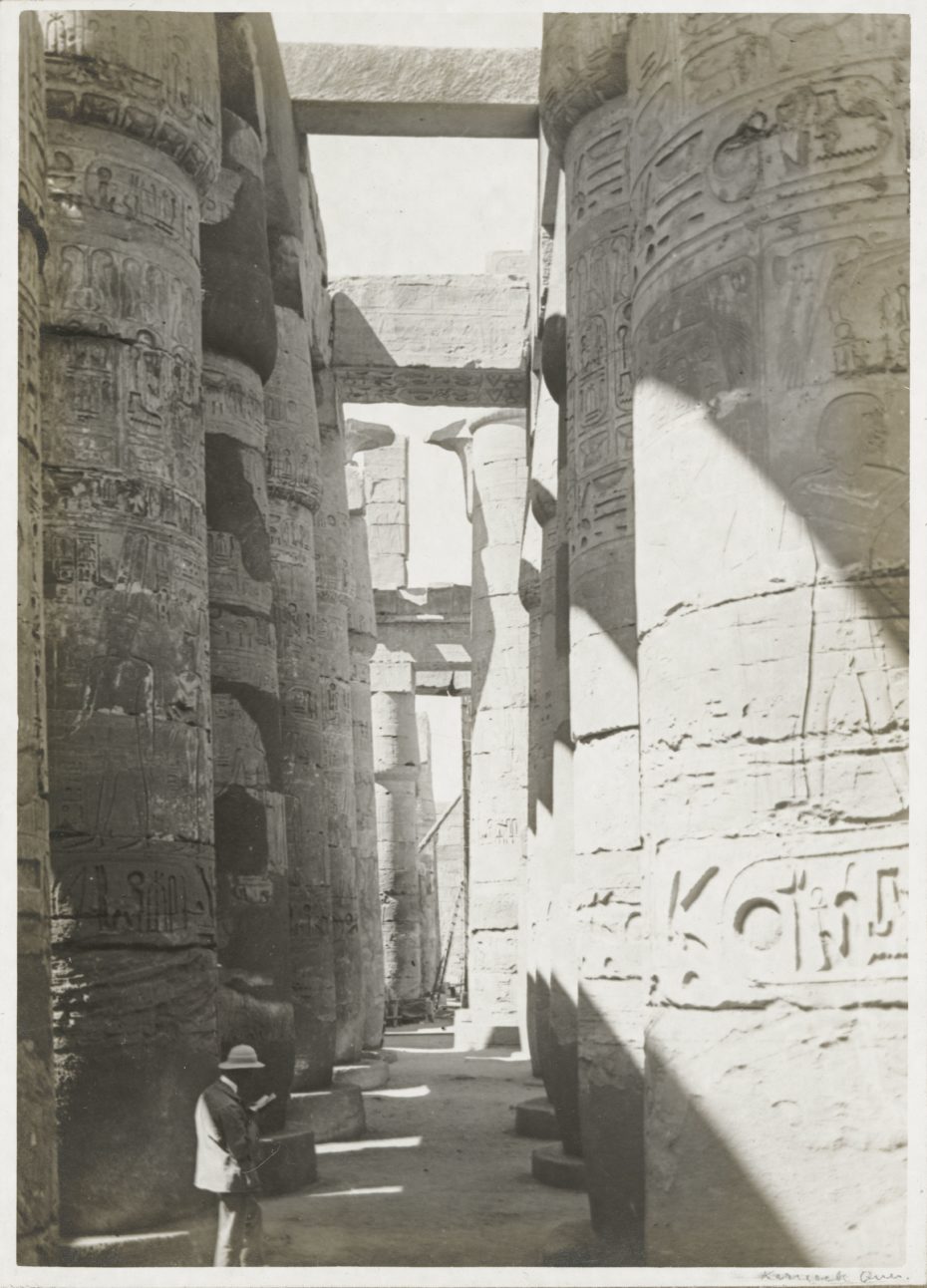

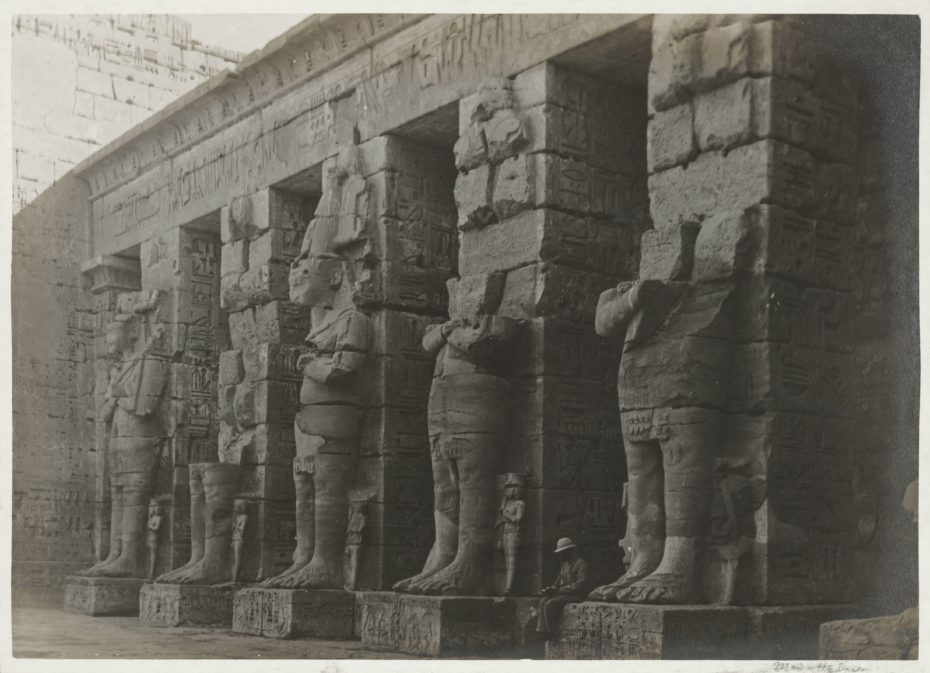

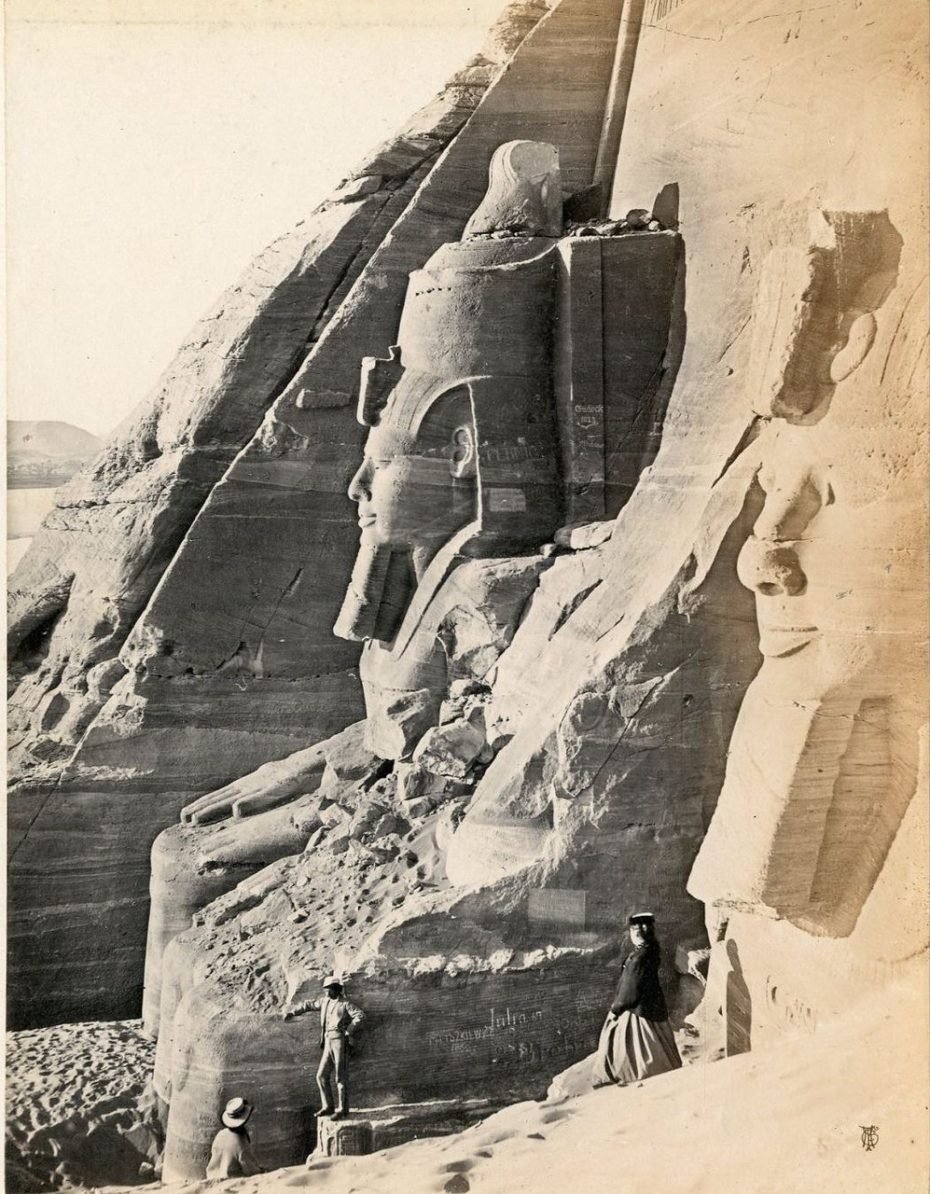

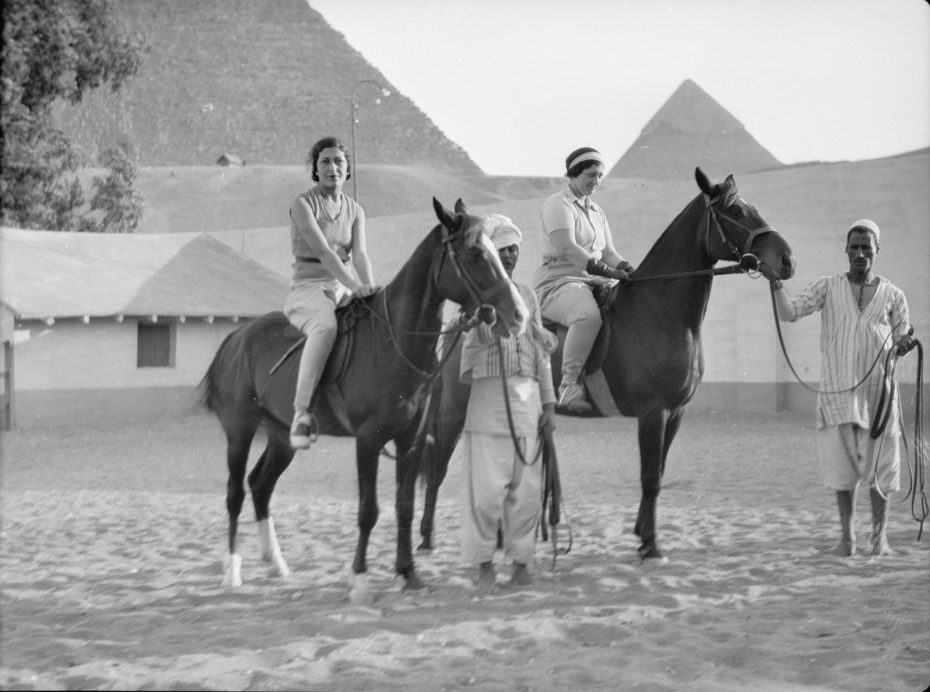

Here at MessyNessyChic, I try to take you on a journey with me every time you visit our corner of the internet. And for today’s journey, I’ve decided we shall go to Egypt– a century back in time, that is. Picnicking in the temples of Luxor, clambering up the pyramids of Giza for afternoon tea and witnessing the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb, we’ll do it all through the camera lens of Egypt’s early-bird tourists.

We tend to forget that Egypt was one of the first locations tourism expanded to outside Europe. It was the beginning of Egyptomania, a cultural reawakening and appreciation for all things Egyptian that swept the world off its feet.

In 1822, Jean-François Champollion was the first to decipher hieroglyphs using the Rosetta Stone which Napoleon’s troops had found during the French invasion of 1799. The rise of scientific Egyptology gradually drew more adventurous westerners across the Mediterranean and up the Nile, wearing white linens and clutching the earliest guidebooks.

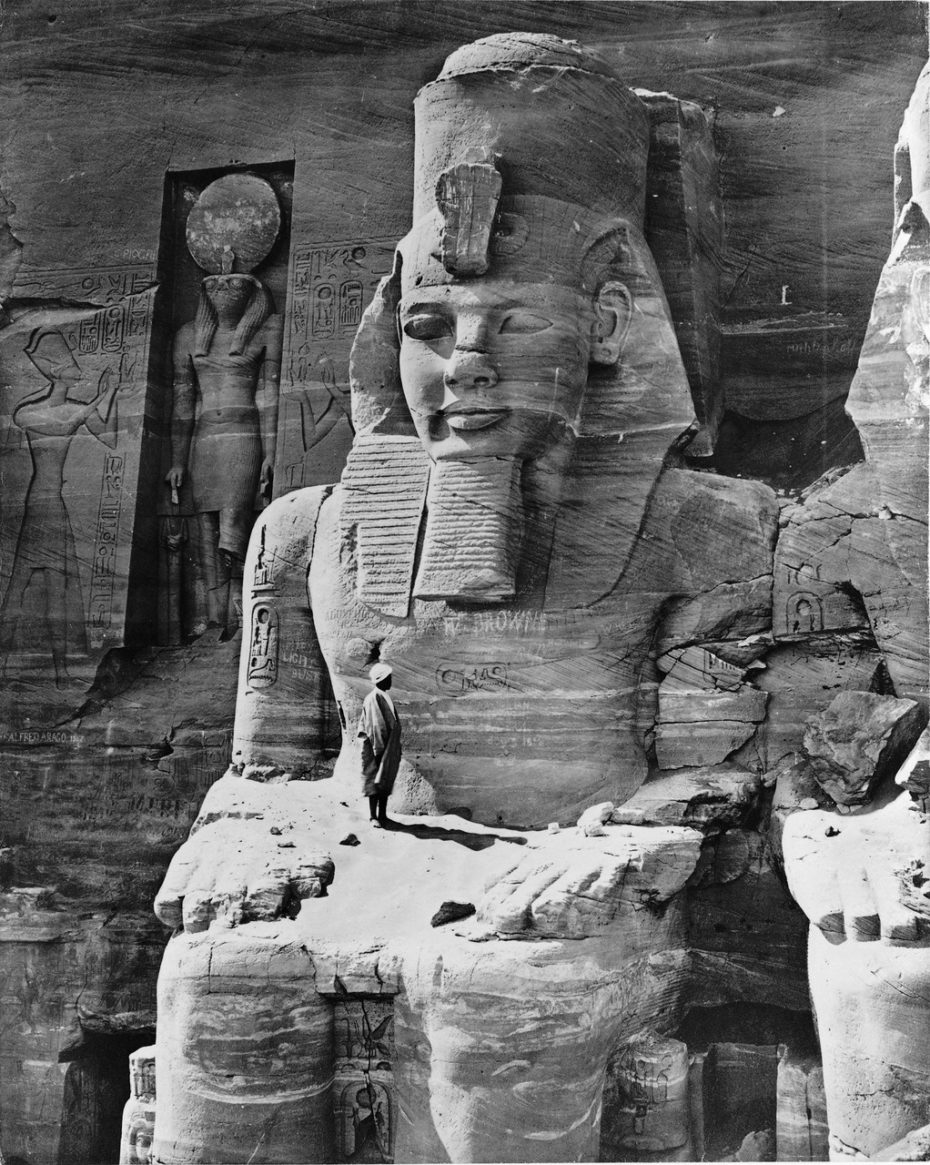

Egypt catered to many different interests and tastes of the 19th century tourist. Romantics no doubt sought the excitement they’d read in popular tales of Ancient Egypt’s mysticism and exoticism while others simply sought better health by wintering in the Middle East with the bonus of visiting some architectural wonders. Until the 1870s, the principal way they traveled around was along the Nile in a dahabiya, a large houseboat with cross-sails. A forty-day round trip from Cairo to Luxor in the 1850s then cost about £110, the equivalent of £12,856 today.

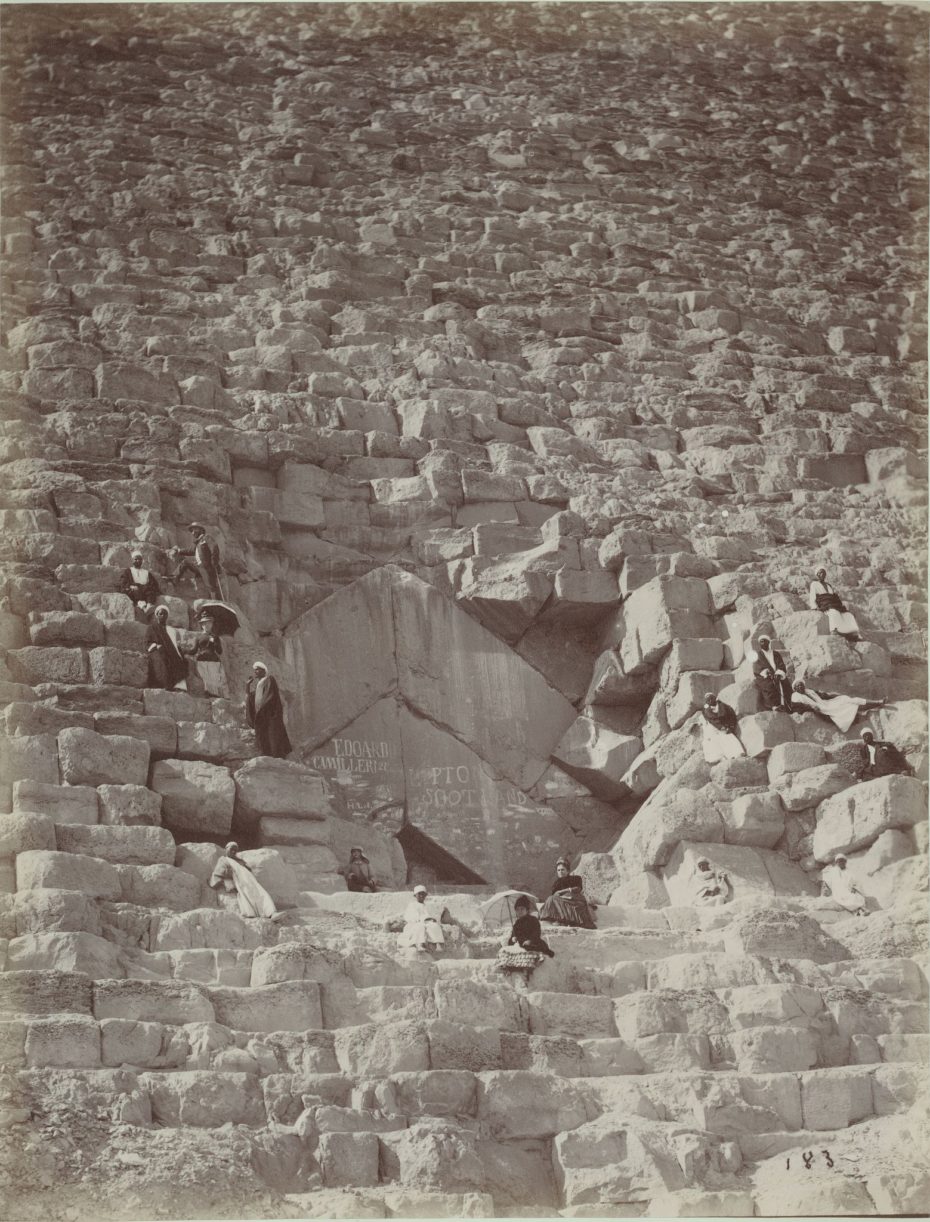

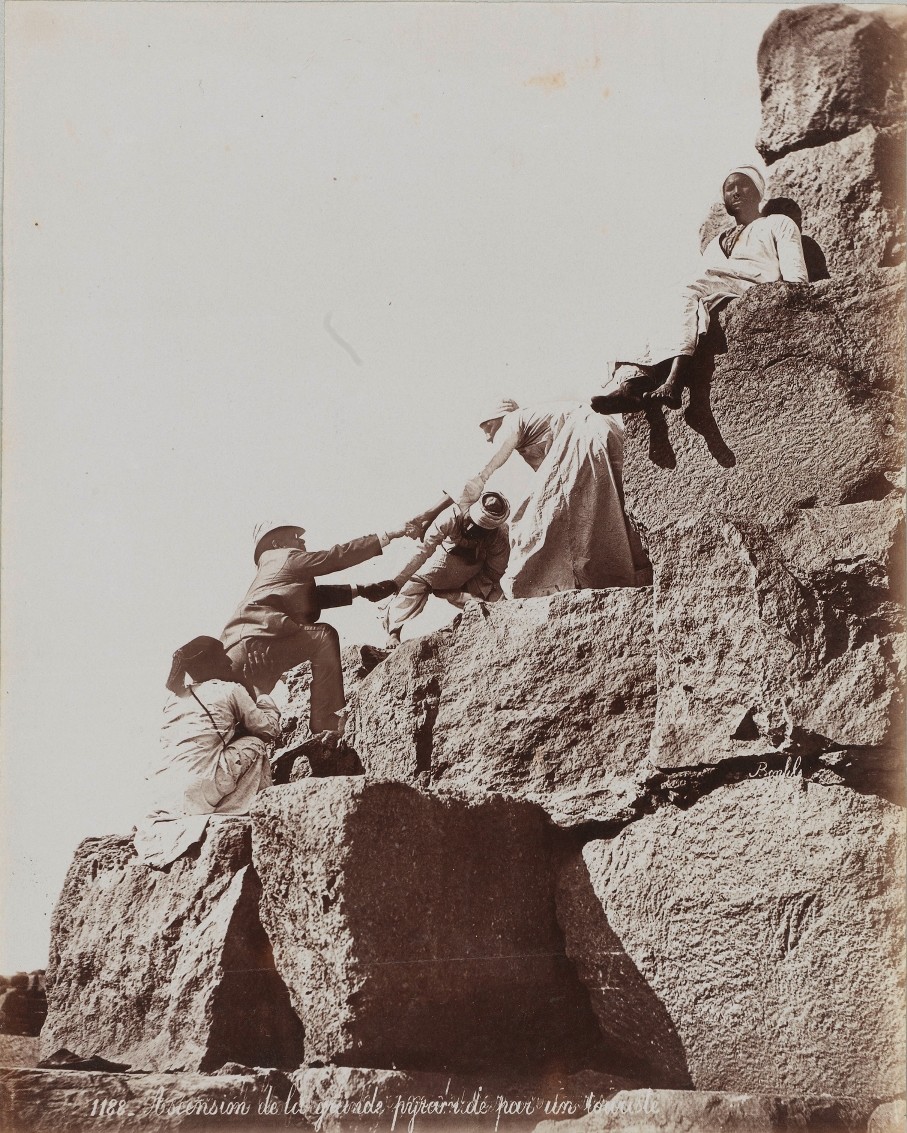

Back then, tourists were able to climb the pyramids, which is no longer permitted. During the winter of 1889, Andrew Dickson White, the first president of Cornell University recounts his experience climbing the ancient edifice:

I went with our whole party to the Great Pyramid, and […] went to the “King’s Chamber,” in the centre and then to the summit. It is hard work, but the excitement kept me up. I had two big Arab guides, Ibrahim and Ali, and behind me a sort of supplementary servant carrying a jar of water and lending a hand now and then. Coming down, this latter personage unrolled his turban and tied the long piece of strong white cloth about me and held the ends, so that no harm would come if I happened to stumble. But no accident occurred of any sort. The view from the top is wonderful. Going into the interior was even more difficult, and much more impressive-though that is saying much. It was hard to realize that the empty royal sarcophagus was placed there long before Abraham and Moses knew anything about Egypt. (White 1888-89: 292)

If they weren’t hauling them up a pyramid or guiding their donkeys across the dunes, the local population had very little contact with the average 19th century tourist. The power dynamic was highly unbalanced and photographs collected by westerners at the time clearly illustrate this fact.

Much of the power in Egypt at this time was held by the French and the British and tourist regulations favoured the interests of European and American travellers, as well as collectors, particularly when it came to the protection of local antiquities. The local governors of Egypt did try in some small way to balance this by requiring passports for entry into Egypt and initiating customs checks.

With the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869, visits by wealthy tourists increased. That same year, travel mogul Thomas Cook, credited with being “the founder of modern tourism,” offered his first tour of Palestine and the Nile. His descendents launched regular steamer trips on the great river in the following years and developed the infrastructure for a vibrant tourism industry in Egypt.

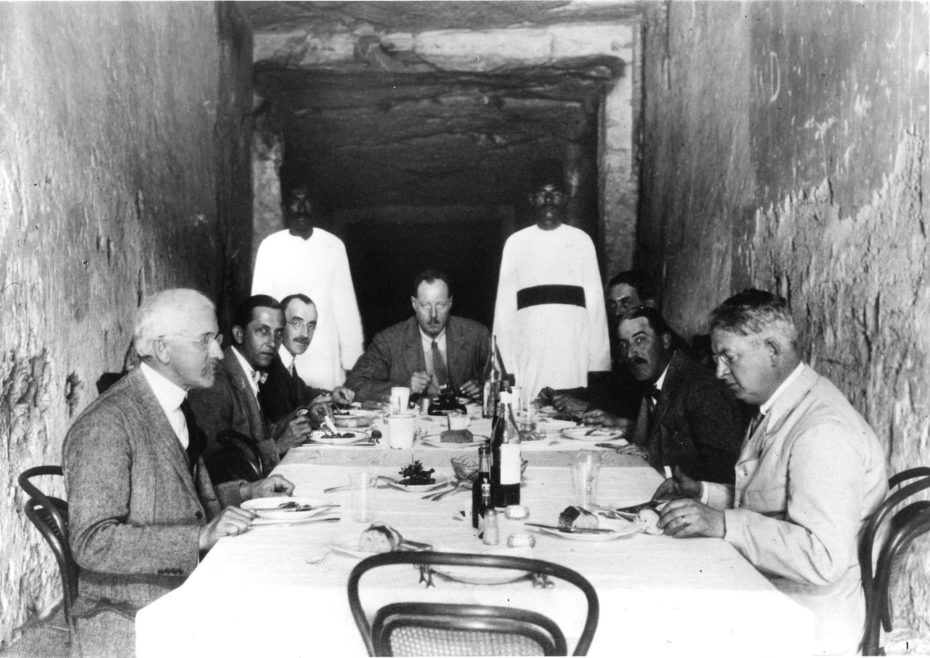

“By the turn of the century, there were two empires on the Nile,” writes historian F. Robert Hunter, “Britain’s military occupation, and Cook’s Egyptian travel. The Nile had become the favourite winter resort of westerners. A traveller could leave his native shores and find the comforts of home aboard a steamship and in luxury hotels bathed in desert sunshine”

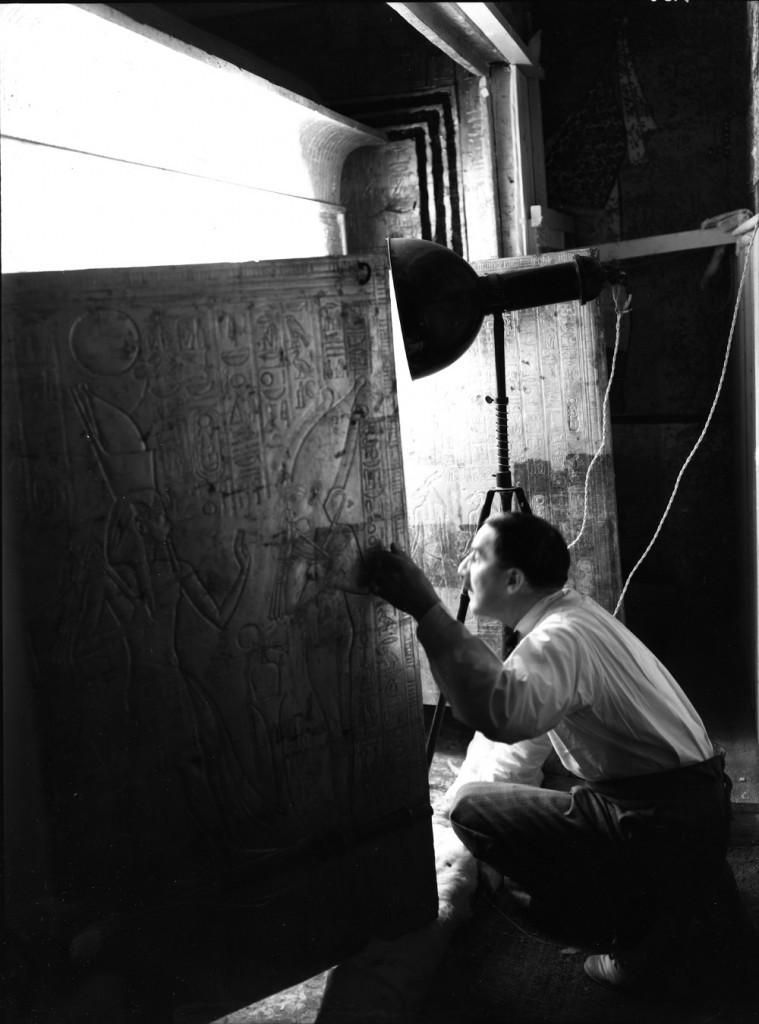

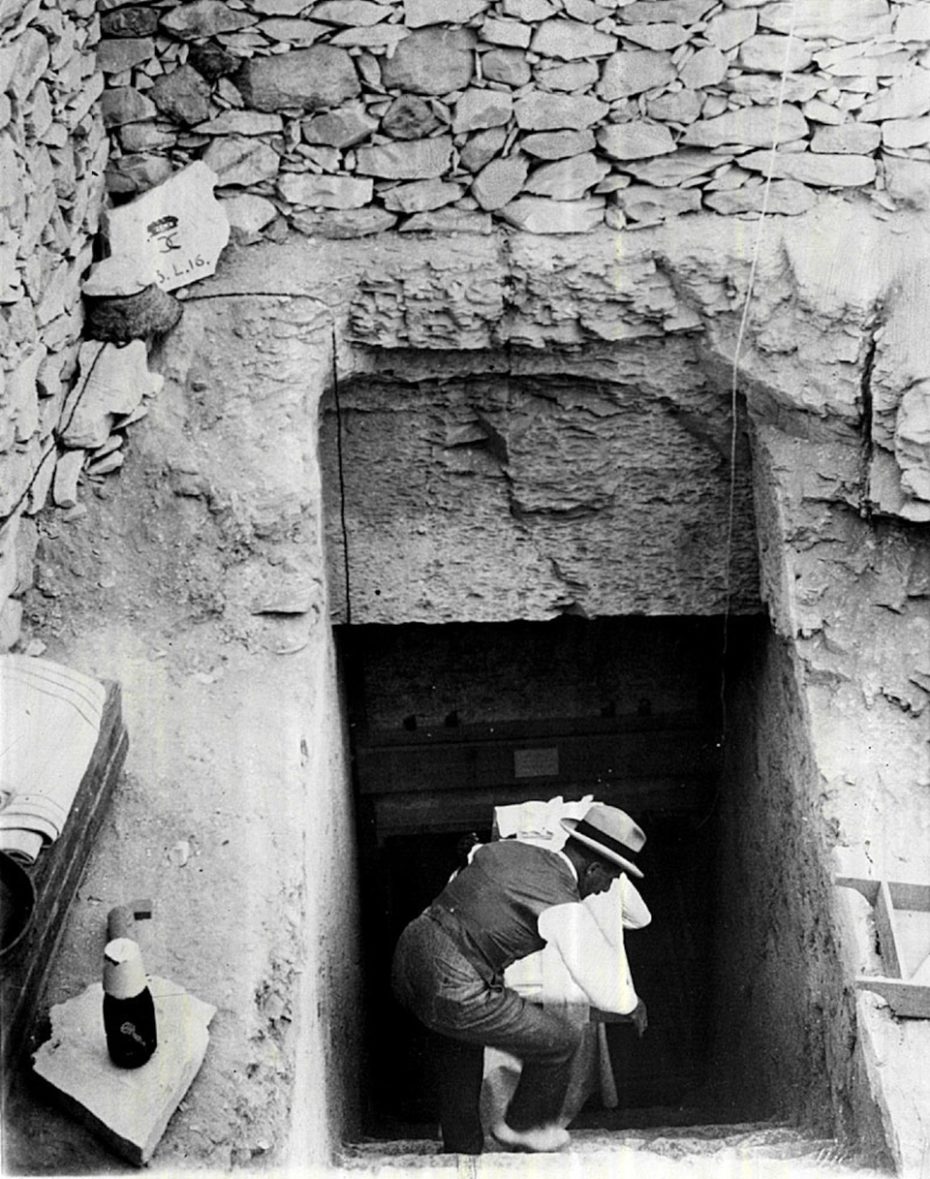

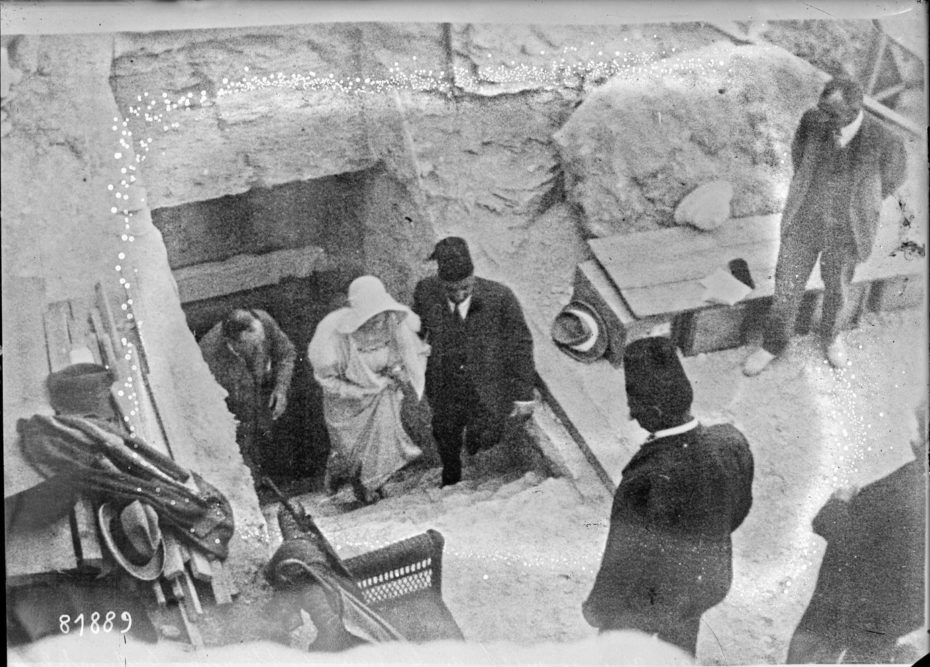

It was of course, the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb however, that changed everything. And Egyptomania became ‘Tutmania’. When Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon discovered the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, ancient Egypt took the world by storm once again and renewed Egyptian fascination among Europeans.

Despite his lack of experience, Carter had managed to land himself the title of chief inspector of antiquities for Upper Egypt by the age of 25. He had a good relationship with the locals and even lost his position as Chief Inspector when he defended some of his Egyptian site guards in an argument with drunk French tourists. Rather than apologize to the tourists, he resigned. It wasn’t until his late 40s that he met the wealthy Lord Carnarvon and convinced him to bankroll his search for the tomb of Tutankhamun. After 5 years of searching the Valley of the Kings, Carter found what he was looking for.

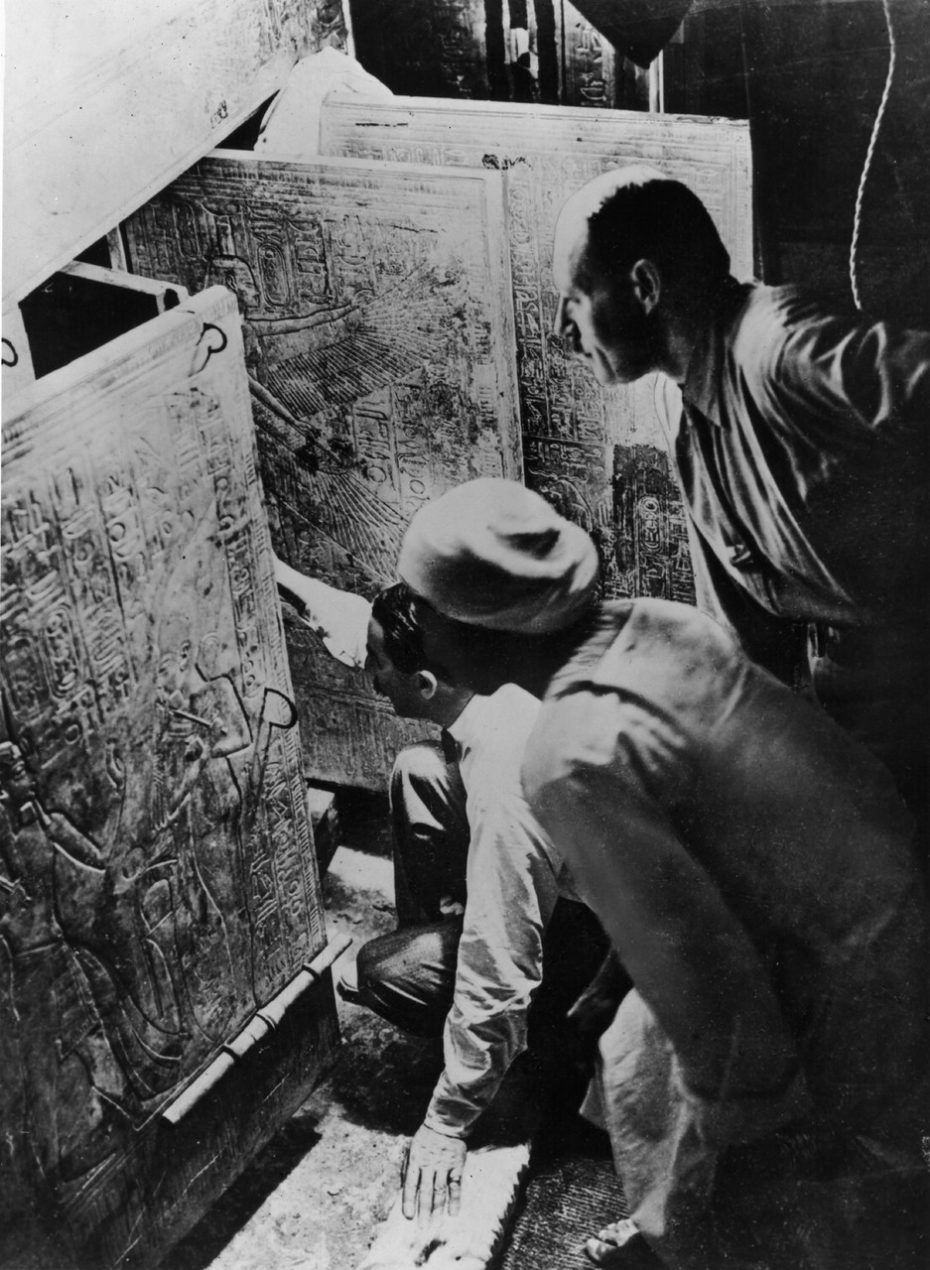

With trembling hands I made a tiny breach in the upper left-hand corner. Darkness and blank space, as far as an iron testing-rod could reach, showed that whatever lay beyond was empty, and not filled like the passage we had just cleared. Candle tests were applied as a precaution against possible foul gases, and then, widening the hold a little, I inserted the candle and peered in, Lord Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Callender standing anxiously beside me to hear the verdict. At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment – an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by – I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, “Can you see anything?” it was all I could do to get out the words, “Yes, wonderful things.

– Howard Carter

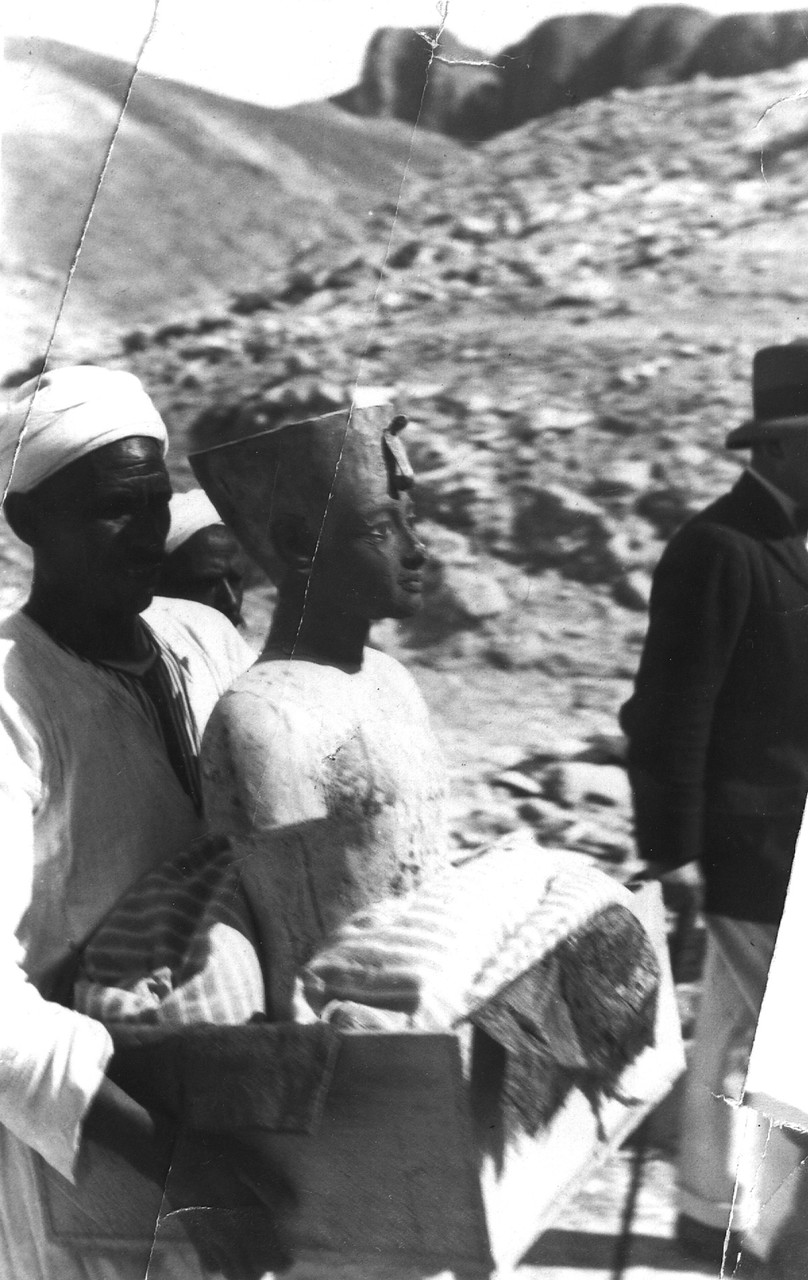

The burial chamber was so small that Carter couldn’t open the shrines on site. Instead, he had to take them apart and move them piece by piece—a process that took 84 days. He even built a rail system to take the pieces of the shrines to the Nile, where they were transported by ship to the museum in Cairo.

It was not only the discovery itself that ignited public curiosity, but also the tale of the mummy’s curse, which supposedly killed Lord Carnarvon (whose castle was used as the house in Downton Abbey) shortly after entering the tomb in 1923. His death was probably caused by blood poisoning from a mosquito bite, but a superstitious world at the time blamed the ‘Mummy’s Curse’.

Howard Carter’s lucky discovery redefined culture during the Roaring Twenties, shaping the visual arts, and creating a prime market for some of the most impactful films of successive decades.

An archaeologist is the best husband a woman can have. The older she gets, the more interested he is in her.

– Agatha Christie

It was the Sudan, the boat gifted to King Fouad in 1885 which carried author Agatha Christie in 1933 and which she used in her famous novel, Death on the Nile. The boat still sails to this day and happens to be firmly at the top of my traveller’s bucket list. One can even stay in the Christie’s suite, where she stayed accompanying her husband on an archaeological mission. If you’re looking to recapture the romanticism of 1920s Tutmania, look no further than a cruise aboard the Sudan.

As tourists have stayed away from Egypt in the current political climate, Egyptology is still alive and well, and much of the ancient civilisation is still being uncovered. In the Valley of the Kings, there is an ongoing search for another tomb hidden behind that of Tutankhamun that may hold similar treasures. At Giza, research suggests there may be hidden rooms inside the largest of the pyramids.

Seeing Egypt’s treasures in museums and books can never truly be put into any kind of context until one decides to make the journey. I only hope these visual journeys alongside yesterday’s pioneers can inspire the adventurer within…