The first thing to know when walking around Levittown, PA, is that it is very easy to get lost. The leafy winding streets often double back on themselves, and confusingly, the street names in the different parts of town not only all begin with the same letter, but have similar sounding, idyllic names; Shadetree Lane, Silverbirch Lane, Strawberry Lane and Sweetbriar Lane. Venture a few minutes north and Magnolia Drive leads into Marigold Lane, Maple Lane, Mistletoe Lane and Meadow Lane, laid out in a pattern not unlike gently undulating waves on a beach.

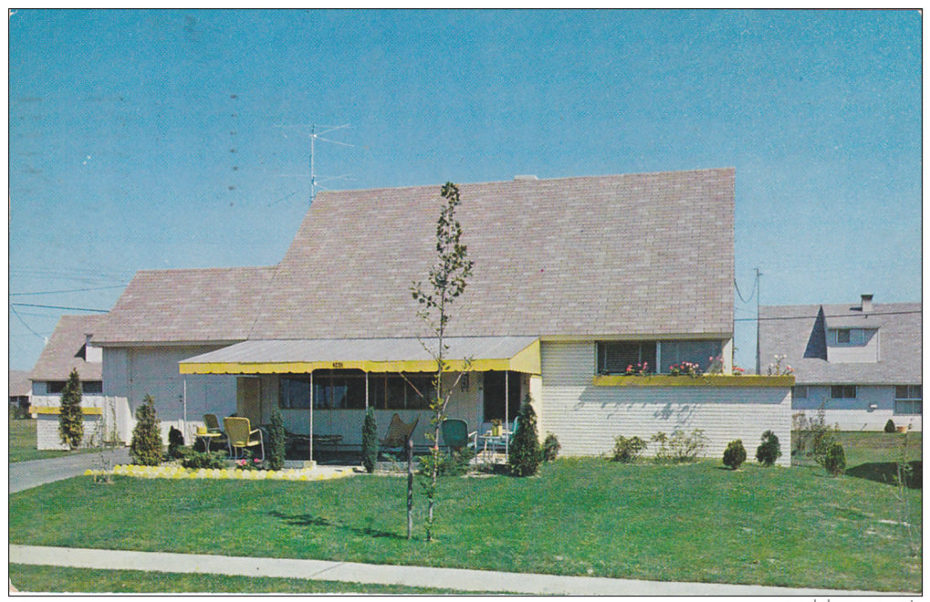

But even more confusingly, the eagle eyed will begin to notice something slightly peculiar– for all the houses in Levittown look almost the same. You might begin to think you’ve stepped into an episode of the Twilight Zone or The Stepford Wives, set in a picture perfect, well-manicured American suburb. Welcome to Levittown!

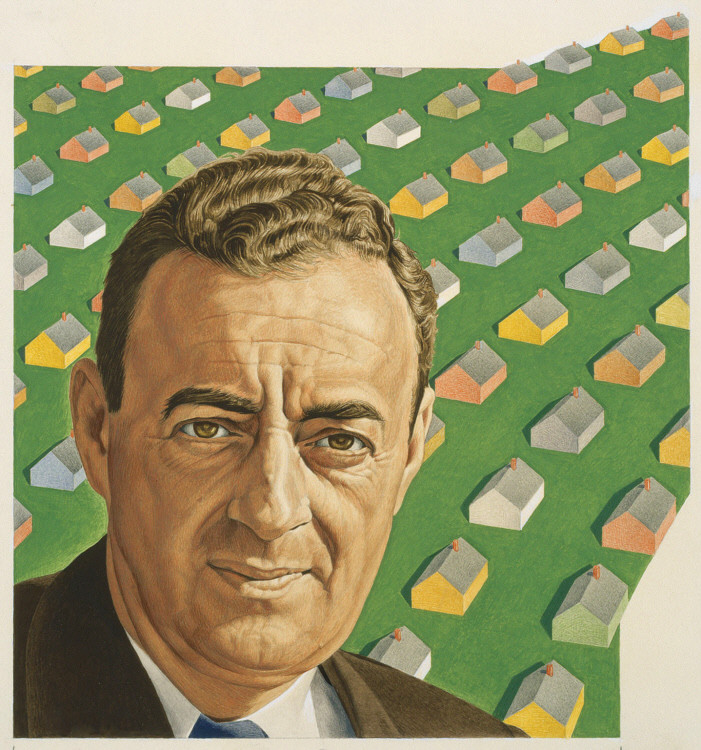

Levittown is located about 25 miles north east of Philadelphia. You won’t find it on any maps made before World War II because it didn’t exist. Levittown was the brainchild of William Levitt. It was to be a utopian, American suburb, created out of nothing; a fully planned, complete town for about 70,000, living in pre-designed homes that came out of a catalogue.

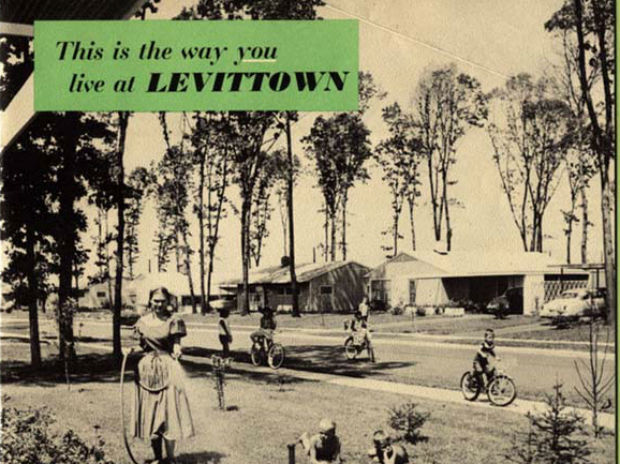

Levitt had pioneered his suburban dream in Long Island after World War II. It was the first truly mass-produced suburb, regarded as the archetype for postwar American suburbia. Advertising enthusiastically promised potential buyers that it was “the most perfectly planned community in America!”

William Levitt drew inspiration from the way Ford made his motorcars along an assembly line process. During his service in the Navy in the war, Levitt saw the way mass manufacturing was harnessed to rapidly produce ships. Why not use the same techniques to build modest suburban homes?

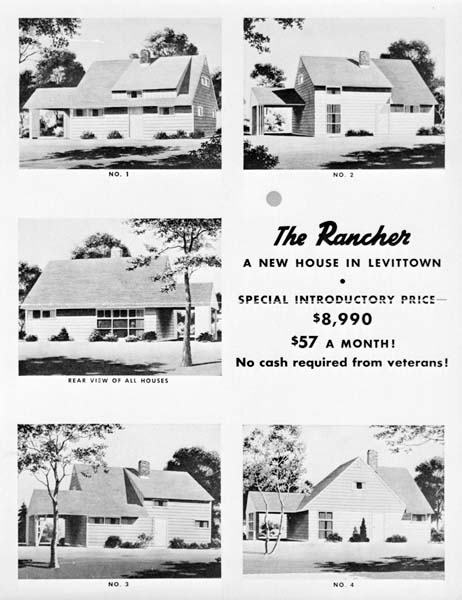

Long Island proved to be a successful start. You could buy a Levitt home for as little as $57 a month, with around $100 as a downpayment. If you were a returning veteran, the downpayment was free.

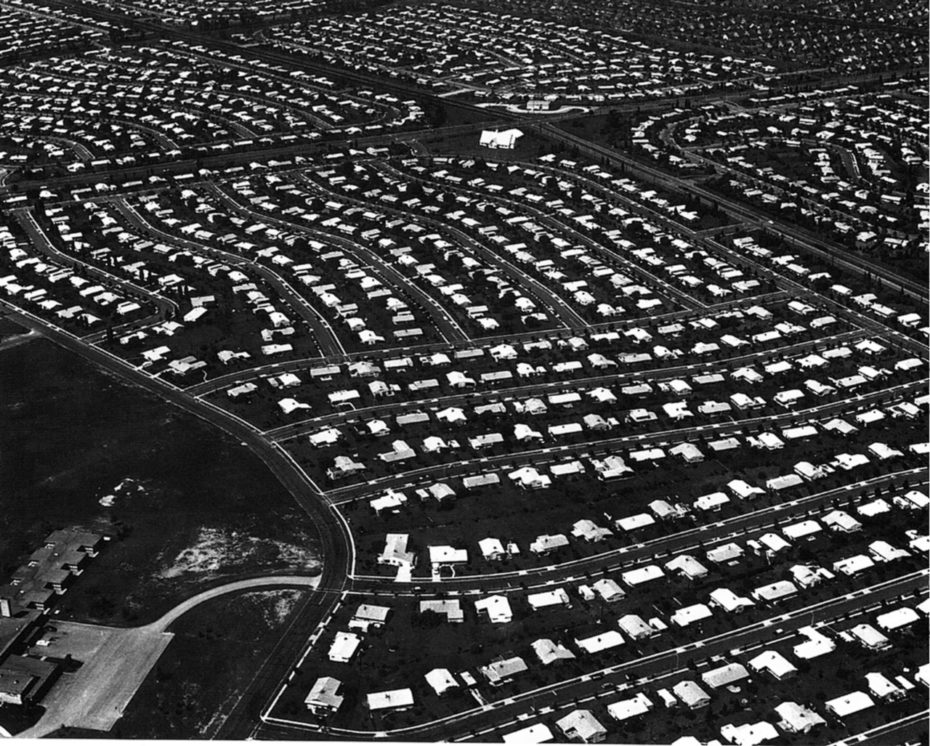

But it was in Pennsylvania that Levitt’s grand dream was realized. Buying nearly 6,000 acres of unused land, Levitt began designing an entire utopian town from scratch. Having honed his assembly line process on Long Island, Levittown, PA bloomed almost overnight. Non-unionized workers were given a specific job– one would install windows, one would wire lights, one would hook up washing machines. They would simply move down the street from house to house, building their one component. If everything went smoothly, in just twenty seven steps, Levitt could build you a home in one day.

Levittown was a roaring success. The chance to afford a nice, family home in a quiet, wholesome town had obvious appeal to those returning from the battlefields of World War II. The first family moved into Levittown on June 23rd, 1952. When Levitt’s town was completed just six years later, he’d made over 17,000 homes in his model suburb. At its height, Levitt and Sons were finishing a home every sixteen seconds.

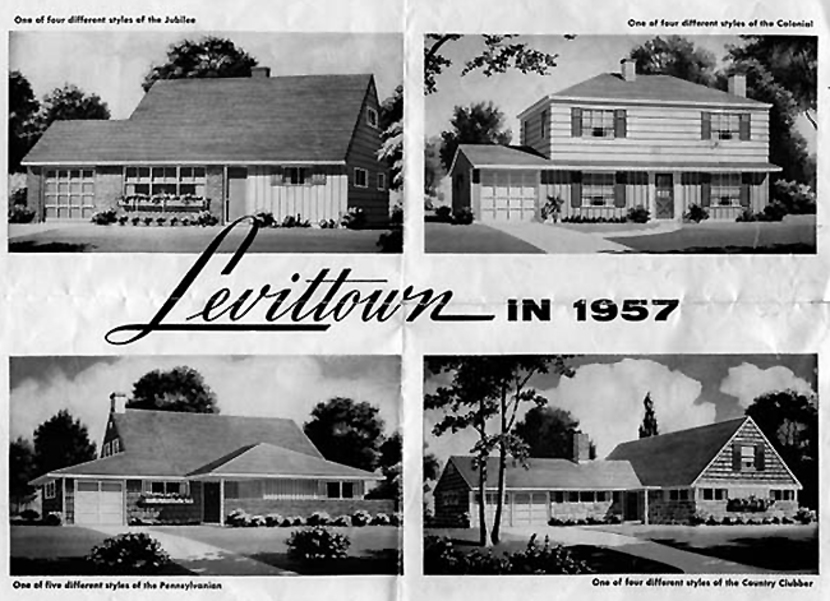

Choosing a Levitt home was a simple process. Stopping in at the showroom you could choose from just six types of home. Starting with the modest Rancher and Jubilee, to the slightly more swankier Levittowner and Pennsylvanian, up to the Colonial and Country Clubber. Your biggest choice was to pick the street you wanted to live on.

But Levitt’s vision stretched beyond just making money through real estate; he wanted to create a perfect, model community. Levittown was subdivided into smaller townships. Each township’s streets would all begin with the same letter. Surrounded by a fence, each township would include their own church, school, park and swimming pool. The curvilinear streets were laid out with no four-way intersections, an attempt to keep traffic peaceful.

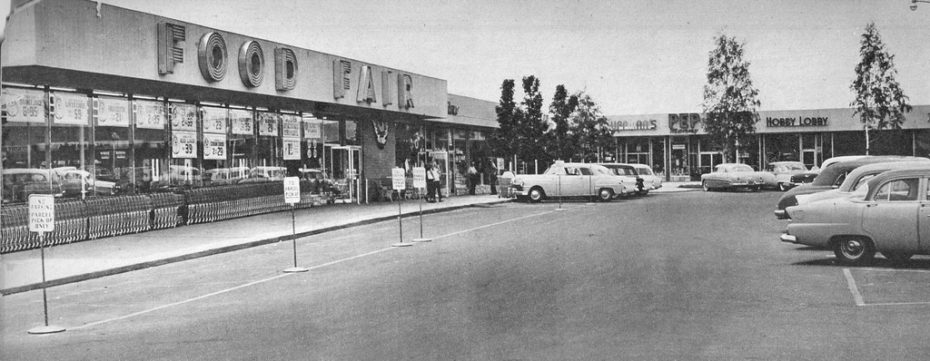

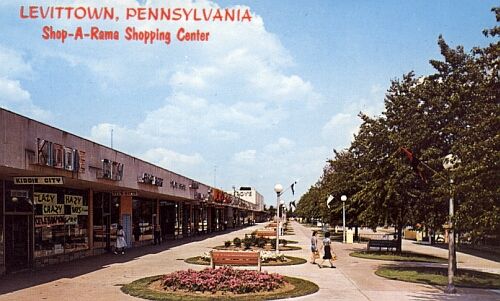

Walking around the suburban streets, one notices that there are no stores, corner shops, bars or restaurants. Levitt designed his town with main thorough fares running between the townships, where he put all his commercial businesses. He built a central shopping precinct, laid out like a baseball diamond, with department stores he called the Shop-O-Rama.

But what was it like to live in Levitt’s planned community? Walking through the townships of Crabtree Hollow (streets include Crabtree Drive, Cherry Lane, Chestnut Lane, Cornflower Lane) through to Holly Hill (Holly Drive, Huckleberry Lane, Hollyhock Lane, Honeysuckle Lane), and onto Apple Tree Hollow (Apricot Lane, Almond Lane, Azalea Lane etc) you notice that there are not many people about, even on a Saturday afternoon. Armed with a 1957 Levittown catalogue, you can quickly begin to notice the six different styles of Levitt home – the long porch of the Levittowner for instance, or the overhanging eave on the Jubilee.

In a bar on one of Levittown’s main streets – New Falls Road, I came across a group of old Levittowners, most of whom have lived there all their lives. One still lives in the original Jubilee his father had bought after World War II. “There was a rule book”, he explained. “It came with the house. You weren’t allowed to hang your laundry in your garden on a Sunday. You couldn’t fence off your yard.” If you broke Levitt’s rules you would be liable for a fine. But the general consensus in the bar was that Levittown was a nice, quiet place to live.

For the same price as renting a cooped up apartment in Philadelphia, you could afford an actual home, that came complete with a television, washing machine, and two trees in your garden– one fruit and one according to your township (Magnolia or Holly etc).

©Luke J SpencerWilliam Levitt was at the forefront of the huge move from the city to a commuter suburbs. A move Levitt hoped would be so wholesome, that one his schools in Levittown was actually named after Walt Disney.

©Luke J SpencerWilliam Levitt was at the forefront of the huge move from the city to a commuter suburbs. A move Levitt hoped would be so wholesome, that one his schools in Levittown was actually named after Walt Disney.

But as with many aspects of 1950’s America, there was a darker undercurrent to his post-war, idyllic town. Whilst Levitt’s rule book – with its ‘no laundry’ on Sundays – seems quaint today, one of his other rules, is far less so. Levitt stipulated that his homes could only be sold to ‘those of the Caucasian Race’.

Levittown was also rooted firmly against the spectre of advancing Communism.“We are not builders”, Levitt once said. “No one who owns his own house and lot can be a Communist. He has too much to do.”

In 1957, Bea and Lew Wechsler sold their Levittown home on Deepgreen Lane in Dogwood Hollow township to an African-American couple, William and Daisy Myers. Ugly newsreel footage shows the shameful race riots that led to police clampdown in the supposed genteel, cookie-cutter small town. William Levitt was taken to court to force integration in his model towns.

Levittown’s mission to create the idyllic, all-white American town would also give rise to the suburban angst found in novels such as Richard Yate’s Revolutionary Road. Yates wrote of, “a blind, desperate clinging to safety and security at any price, as exemplified politically in the Eisenhower administration and the McCarthy witch hunts.”

Urban historian Lewis Mumford was less kind; “the suburb served as an asylum for the preservation of illusion. Here domesticity could prosper, oblivious of the pervasive regimentation beyond. This was not merely a child-centered environment; it was based on a childish view of the world, in which reality was sacrificed to the pleasure principle.

William Levitt would go on to build several more towns, Willingboro in New Jersey, Bowie in Maryland, and another Levittown in Puerto Rico. But Levitt still refused to sell his model homes to non-Caucasians, and in the face of federal court orders, sold his company in 1967.

Today, Levittown, PA, remains a peculiar chapter in post-war American history. The rows and rows of curved, similar sounding streets are matched by the rows and rows of similar looking homes. Still today, the population is almost entirely white, and centered around their pre-fabricated schools, churches and village greens.