Note: portions of this article contain graphic text.

You couldn’t have concocted an eerier murder mystery if you tried. Yet, history seems to have bookmarked the case of the Missing Women of Perpignan — “Les disparues de Perpignan”, as the French say — with dwindling media attention; a shocker due not only to the case’s bizarre nature, but the fact that it implicated Salvador Dali as a driving factor behind the four, grisly deaths of four young women in France in the 1990-2000s.

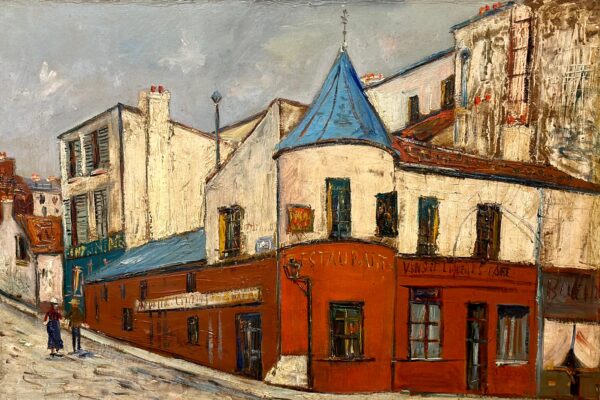

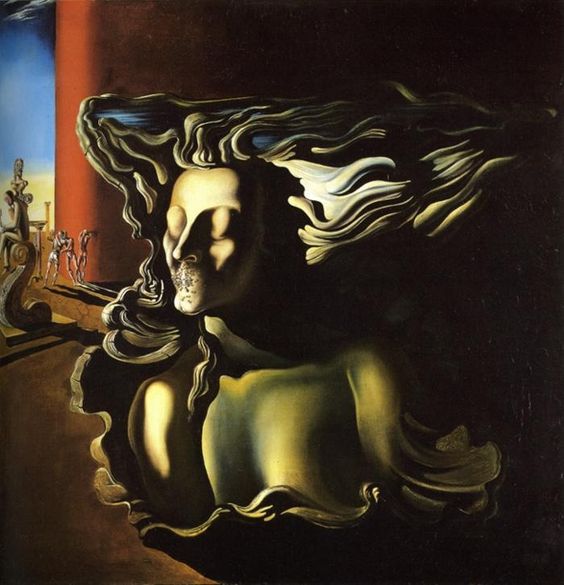

Ballerina in a Death’s Head by Salvador Dali, 1939.

At the heart of the case is Perpignan, a sun-soaked city in the Languedoc-Roussillon region by the French-Spanish bordeer, whose main claim to fame is thanks to the famous Surrealist artist. In August of 1963, Dali stepped off the train, and, in complete ecstasy, declared its station “the centre of the universe”.

The train station.

“Dali’s curiosity for the train station stemmed from his belief in the philosophy of cosmogony,” says a representative of the city’s Tourism Department, “Cosmogony is the theory there is a single universal origin from which all existence and reality emerged…arriving at La Gare de Perpignan is like entering the centre of (his) psyche.”

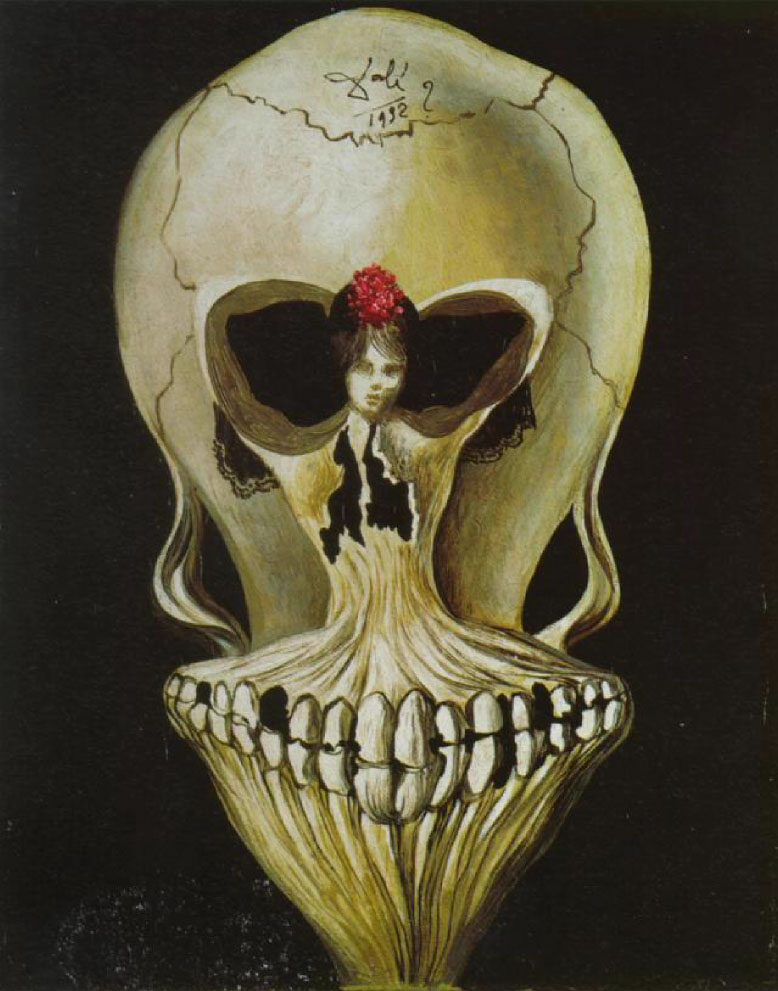

Dali at Perpignan train station

Not everyone is convinced. “It’s open to debate whether the rather drab outpost of France’s SNCF is a mystical edifice in which ‘all parts of the Earth converge,’ contested an LA Times journalist in 2004, “and that, as Dali maintained, the train station predates the pyramids of Egypt and once saved Europe from devastation when the continental plates split apart.”

Regardless, it became the centre of Dali’s universe (and art):

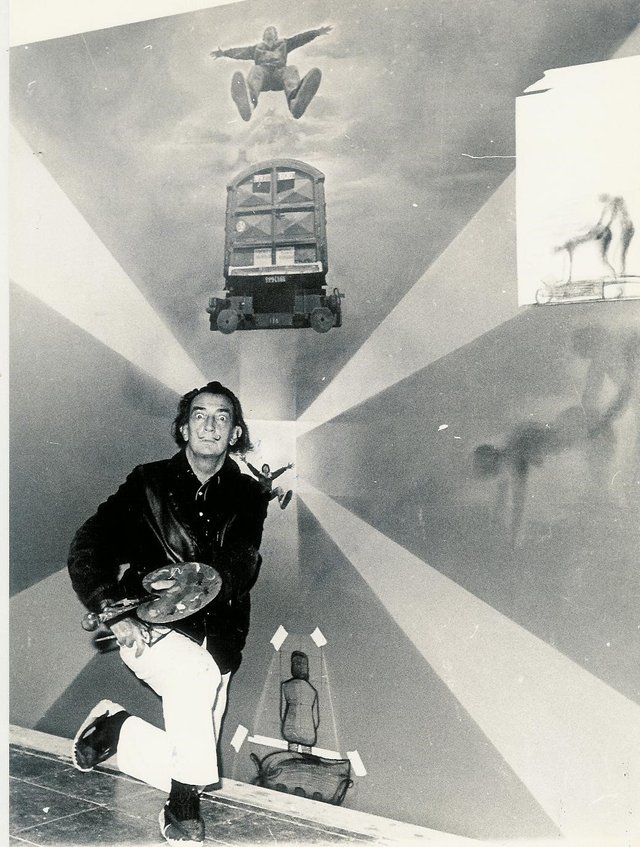

“The Railway Station at Perpignan” includes a depiction of a man preparing to sodomise a young woman.

Then, in the 1990s, the train station’s neighbourhood became the centre of the murders of Tatiana Andujar, Marie-Hélène Gonzales, Mokhtaria Chaïb and Fatima Idrahou (pictured below, respectively).

It all started when police got a call in the middle of the night. “They said they saw the body of a young woman from their window, in an overgrown lot.” The unclothed body was that of 19-year-old Moktaria Chaib. “She was turned on her back,” explained Perpignan officer José Bellemonte, “arms crossed, chest and body heavily mutilated”. There wasn’t a trace of blood on the site.

“La Gare de Perpignan” by Dali, 1965.

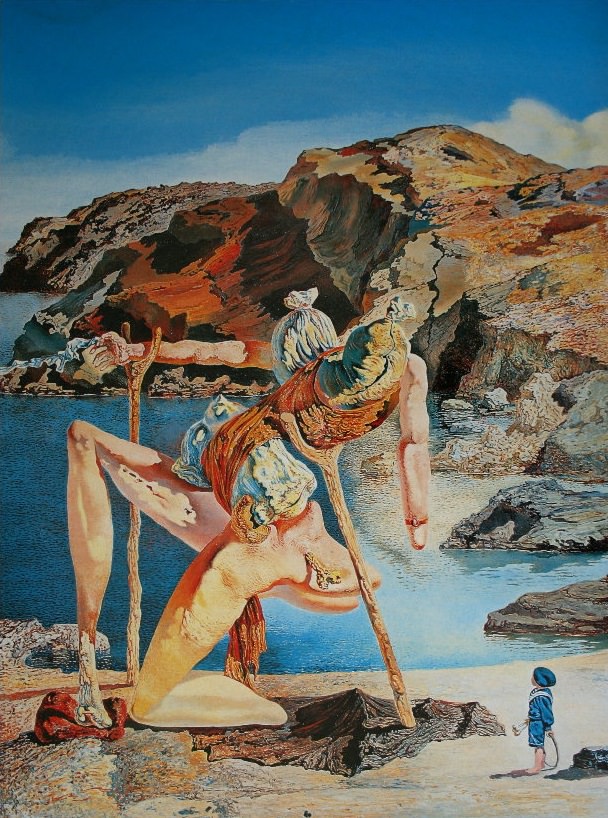

Three more murders occurred in the following years, often revealing a link to the train station quarter and a penchant for ceremonial mutilation done with the precision of a surgeon’s hands. “The Police were stunned,” said journalist Jean-Marc Aubert,”they thought, ‘this must be a kind of sexual, ritualistic crime.”Hélène Gonzales’ head, hands and vagina were removed entirely, and a selection of her internal organs stored in a small box by her side. Dali’s 1932 painting, The Spectre of Sex Appeal, features a female torso with missing head and hands.

The Spectre of Sex Appeal, 1934

For years, the killer remained elusive. But for two detectives, the crime scenes clearly recalled the surreal paintings of Dali, whose complicated relationship with women, death, and sexuality were frequent themes of his work. His obsession with vaginas, says one biographer, stems from a profound “loathing of the female genitalia”.

Dali was transfixed, even traumatised, by female sexual organs. Freud would’ve had a field day with his paintings, whose wasteland settings were filled with dislocated body parts, chicken eggs, and grotesquely erotic symbolism (i.e. unattached genitalia and naked female bodies missing their breasts and womb).

Dali and his wife, Gala.

Dalì himself admitted on several occasions to having sadomasochistic tendencies. As a child, he claimed he enjoyed throwing himself down the stairs. “The pain was insignificant, the pleasure was immense” he said. He also once pushed his childhood friend off of a 15-foot bridge – as his friend lay injured, his mother tending to his bloody wounds, Dali apparently sat there calmly, smiling and eating cherries. In famed collaboration with Luis Buñuel, Un Chien Andalou, the film shows a woman’s eyeball being cut open. In his own biography, “The Secret Life of Dalì,” he even admits that he became interested in necrophilia, but was later cured of it”.

“When it came to Gala, his wife, there was an awe and fear of sexual intimacy,” said a University of Paris art professor, Dr. Chiss.

With their dislocated, floating female body parts, detectives thought Dali’s work might have been a twisted source of inspiration, even blueprint, for the killer. “We’ve looked at it,” one detective told The Guardian in 2000, “It’s improbable. When investigations were reaching a boiling point, police were even commissioning “analytical reports from art experts on the significance of Dali paintings” to look “for anything that could tie in…anything.” In total, over 140 persons were held and released during the hunt for the real killer(s). One lawyer also confirmed that in their attempts to construct a psychological profile of the murderer or murderers, police had examined the extraordinary story of Dali’s obsession with Perpignan.

Then, in 2004, a man named Marc Delpech was finally condemned to 30 years of prison for the death of Idrahou. It wouldn’t be until 2015 that another, Jacques Rançon, admitted to the murder of Gonzalez and Nadjet — and even then, police say the details remain murky. As recent as March 2018, Rançon was in court asking pardon from the victim’s families.

Whether or not Dali’s work can shed some light on the matter isn’t totally out of the question. “I’m not sure what I think,” said the Chaibs’ lawyer at one point, “Maybe it’s madness…But killers are inspired by films, aren’t they? Why not by the painting of the man who made this town famous?”