Madame Ganna Walska

“Don’t touch. And don’t eat what you touch unless you want to die” are the first words you’ll hear upon entering Lotusland, the exotic, 37-acre kingdom of plants tucked away in the quiet town of Montecito, California. Its roots run three owners and 135 years deep, but it’s the touch of its final, failed opera singer patroness, Madame Ganna Walska, that makes the legacy behind its pink walls so magical…

©Lotusland

Our story starts when “Madame” was just 19, and plucked from a crowd by the Czar and declared the most beautiful girl at a ball. Back then she was just Hanna Puacz, your run-of-the-mill Polish gal from a humble family. But when she caught the Czar’s eye, he immortalised her beauty in a commissioned portrait:

She was the perfect cocktail of charisma, beauty, and wit, and quickly rose to the top of society with a new name: Madame Ganna Walska. “Madame” in reference to her budding opera career, “Ganna” as a variation of “Hanna,” and “Walska” because, well, it sounded like “waltz” and she just loved to dance.

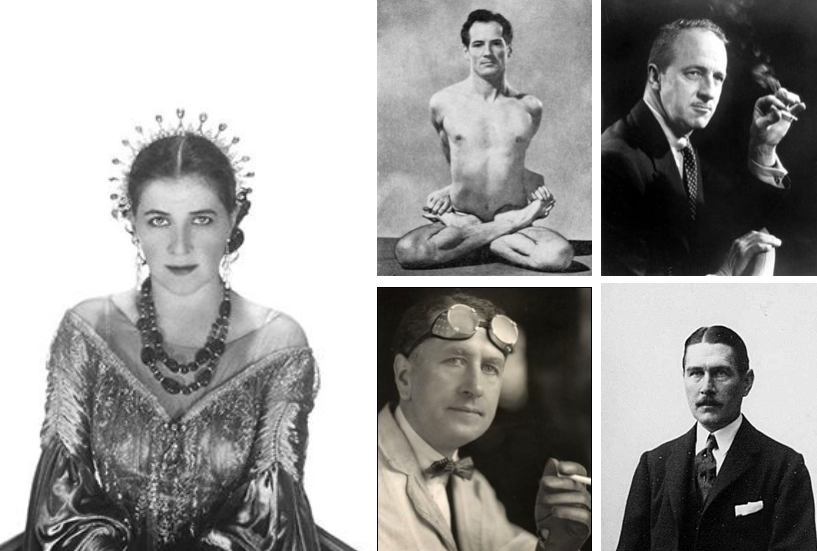

A handful of Madame’s men.

“She collected plants, and husbands. You could say the plants stuck around longer,” explains Christine Gress, our guide through the green labyrinth of Lotusland. Madame accepted numerous marriage proposals and in total had six husbands, including a Russian count, a yogi, a playboy conman and the inventor of an electromagnetic “death ray”.

When she wasn’t playing ‘femme fatale’ and enjoying the high life that her first marriage had introduced her to, a good chunk of her time was spent in pursuit of a career as an opera singer.

The only problem was– Madame Walska couldn’t sing– or at least, if she could, no one was aware of her talent due to a crippling case of stage fright. In 1918, she performed in the Italian opera Fedora before an audience in Havana, Cuba which included fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli. The reception of the performance is described in the designer’s biography:

(…) Cuban audiences were notorious for letting their feelings be known right away. Walska soldiered on. The catcalls and jeers became well-aimed ammunition. Was it flowers or rotten tomatoes? We shall never know. (…) Then act two began, the audience was making so much noise Walska could not be heard. People were standing up and shouting, about to storm the stage.

In 1925, The New York Times headlines of the day read, “Ganna Walska Fails as Butterfly: Voice Deserts Her Again When She Essays Role of Puccini’s Heroine” (January 29, 1925).

Ganna’s fourth husband, Harold McCormick played a vital role in continuing to promote her career, and his promotion was so adament, in fact, that it inspired much of the screenplay for Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, in which the mysterious tycoon loses all his power and instead focuses his energies on his wife’s hopeless opera career.

While she might not have had the “X Factor”, Ganna’s attentions (and wallet) were always oriented towards supporting the arts, and in 1922, she bought Paris’ Theatre des Champs Elysées following her divorce from McCormick. She claimed she bought the theatre (and a French chateau) with the fruits of her own investments, as opposed to those of her ex-husband’s.

“Love comes and goes on its own accord, like a fever,” Madame once said, “Nothing can stop it, nothing can prolong it either…My reputation was entirely my own creation for self-defense… I was considered to be an exceptionally level-headed woman, a thousand-headed monster, a hard working machine.”

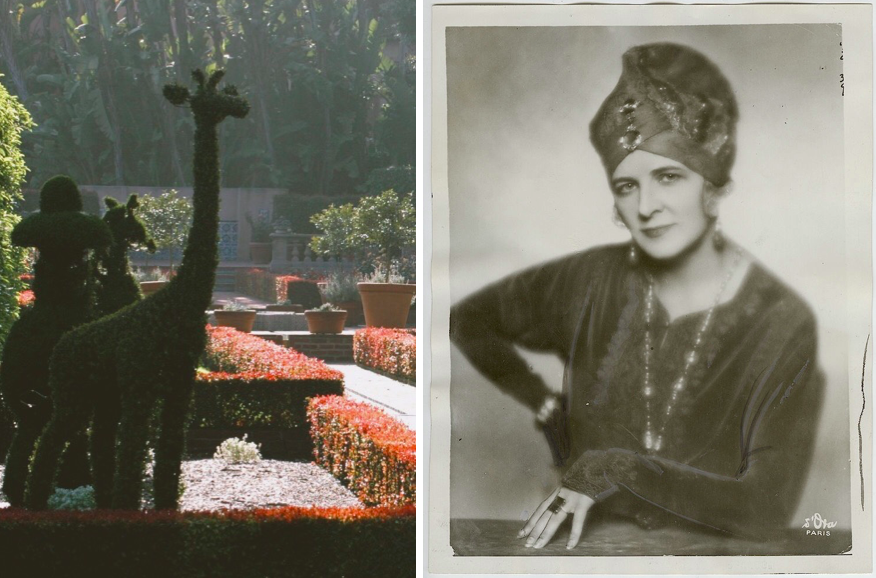

©Lotusland. Madame at home on rue de Lübeck, in the affluent 16th arrondissement:

Madame became quite a fixture on the Parisian society scene, and for a brief spell, had a go at launching her own Parisian cosmetics line. She was heartbroken when the impending First World War forced her to leave Paris for America.

But it was in America that she would find would finally find her calling and begin to shift herself out of the media spotlight that left her exposed to public ridicule and tabloid punchlines.

“I am an enemy of the average” – Ganna Walska.

©Lotusland (left).

In 1941, she bought her Santa Barbara estate from the herbology-obsessed Gavits family, who paved the way for her whimsical embellishments with their dramatic, Italianite landscaping. With the encouragement of her last husband, a yogi known as “White Lama,” she put her energy into what would soon be known as Lotusland, her true creative chef d’oeuvre…

©Lotusland

Ever the francophile, she installed a number of the statues brought over from her French chateau, but it was also important for her to weave in elements of her Buddhist religion into the garden. Upon purchase she actually intended to turn it into a monastery called, “Tibetland,” but in the wake of WWII, the US government refused visas to the mountain monks she had hoped to bring over.

©Messynessychic

One of the gardens is dedicated to lily pads and lotuses, the latter of which give the estate its namesake. The aquatic flower symbolises personal growth and strength in Buddhist tradition, two qualities that would prove very important to Madame.

©Lotusland

The areas are often referred to as “garden rooms,” and categorised rather eclectically; some by country (the Australian), some by plant (Bromeliad) others by colour (i.e. the Blue Garden). This wasn’t just landscaping, but the creation of living, breathing stages.

©Lotusland

Madame took many cues from the park “follies” structures popular during Paris’ Belle Epoque, like the tremendous astrological clock surrounded by topiary beasts. She proudly dabbled in telepathy, the zodiac, and was also a big fan of Ouija boards. (For what it’s worth, her sign was Cancer.)

Then there’s the Water Garden, with its aquamarine pool and giant clam fountains of her own design:

©messynessychic

Later, when she smuggled her Polish family members out of Europe during the Second World War, she would dedicate an entirely new pool to her niece (complete with a faux beach and dangling pelican sculpture).

There’s also a formal theatre garden made up of rows of hedges and populated by a collection of 17th century stone figures called “grotesques.” They’re dwarfish characters from plays by the likes of Molière, and carved by the French artist Jacques Callot. They also tend to pop up out of no where…

©Messynessychic

Tremendous shards of blue-green glass emerge from the paths like emeralds, which Madame called jewellery for her garden and salvaged from an LA glass manufacturer. “She was wealthy,” says Gress, “but she was always thrifty, no matter how successful she became.”

©MessyNessyChic

The Japanese garden is currently under renovation, but its periphery teases you with stone lanterns called “Ishi-Dōrō” for as far as the eyes can see…

©MessyNessyChic

The Insectary Garden is home to butterflies, a tremendous copper cage with doves, and a far-reaching trellis of lemons that Madame called her “Victory Garden,” which was planted for the veterans of WWII. Today, its harvest serves certain food banks of Southern California.

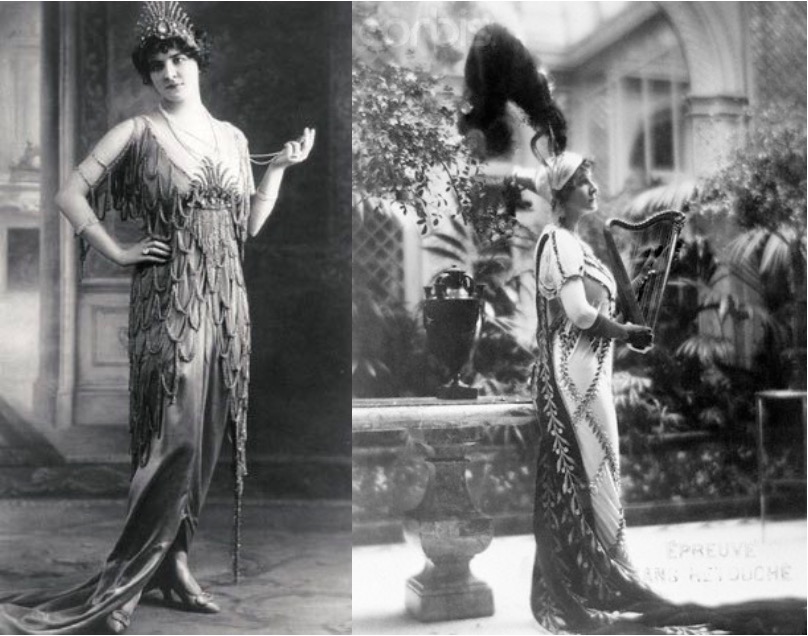

For the most part, her elegant wardrobe, from her costumes to self-titled “Ganna Walska” perfume, are stored in Los Angeles. She had an excellent eye for both costume design (although the talents of Erté and Lanvin helped a lot).

But every once in a while her treasures make an appearance at the old Montecito estate…

©MessyNessyChic

“She loved grand entrances,” says Gress, “Each pathway was meant to feel dramatic, with its rows of agave or palms…her motto was the French phrase malgré tout, “in spite of everything,” because she’d been through so much in love, death, and war over the years.”

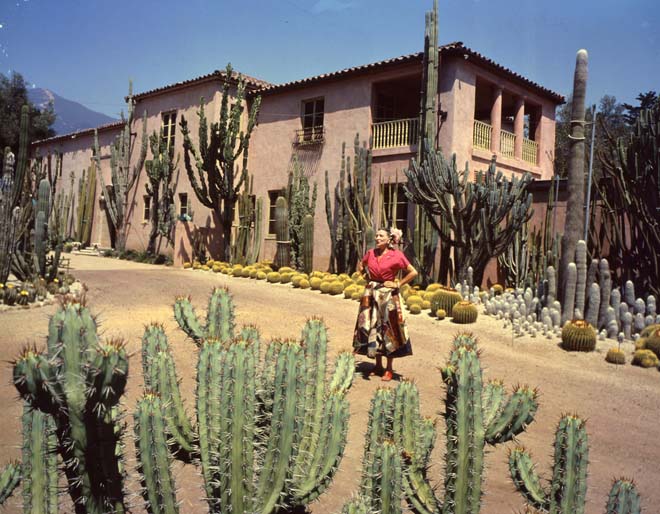

And just as you begin to feel lost in what feels like a very chic Jumanji, you’ll reach the pink main house. It’s at the heart of the garden, and meant to transport you to the sun-baked hills of Mexico…

©MessyNessyChic

Not much has changed today, and one type of cactus at its feet is actually extinct in its native Mexico. But that story isn’t uncommon at Lotusland, which has become one of the world’s most precious sanctuaries for rare plants.

Gress shows the scale of the plant life by the main house. ©MessyNessyChic.

In fact, it’s one of the only places in the world where so many dangerous breeds can be at home. “The U.S. federal government,” says Gress, “has made it one of few holding grounds for plant contraband” (yes, that’s a thing). It’s a kingdom of exotic misfits, with the spirit of the most colourful and resilient of them all, Madame, at its helm.

©MessyNessyChic

When all was said and done, you could say that Lotusland was the true love of Madame’s life, and she lived until the age of 96 in the company of her 3000 darlings (aka plant varieties). One of her last grand gestures to the estate was the auctioning off of $1 million worth of her jewellery in the 1970s in order to finance the installation of (you guessed it) a garden of 500 cycads.

Luckily for us, Madame bequeathed the gardens to the public upon her death, and you can make a reservation to visit it here