© Doug Dupin/ Flickr

The legendary American architect Frank Lloyd Wright never wore his heart on his sleeve. For better or for worse, he dressed up his blueprints in his feelings, and nowhere is that reflex so painfully clear than in his handful of mysterious, pre-Colombian-inspired houses built in California in the early 1920s. You could call them “the Mayan Revival Wrights,” and you might recognise them as Harrison Ford’s dystopian digs from Blade Runner, but few are aware that their eerie, tomb-like style was in fact the byproduct of Wright’s greatest personal catastrophe: the ax murder of his lover, a woman named Martha, and six other people at the architect’s midwestern hideaway…

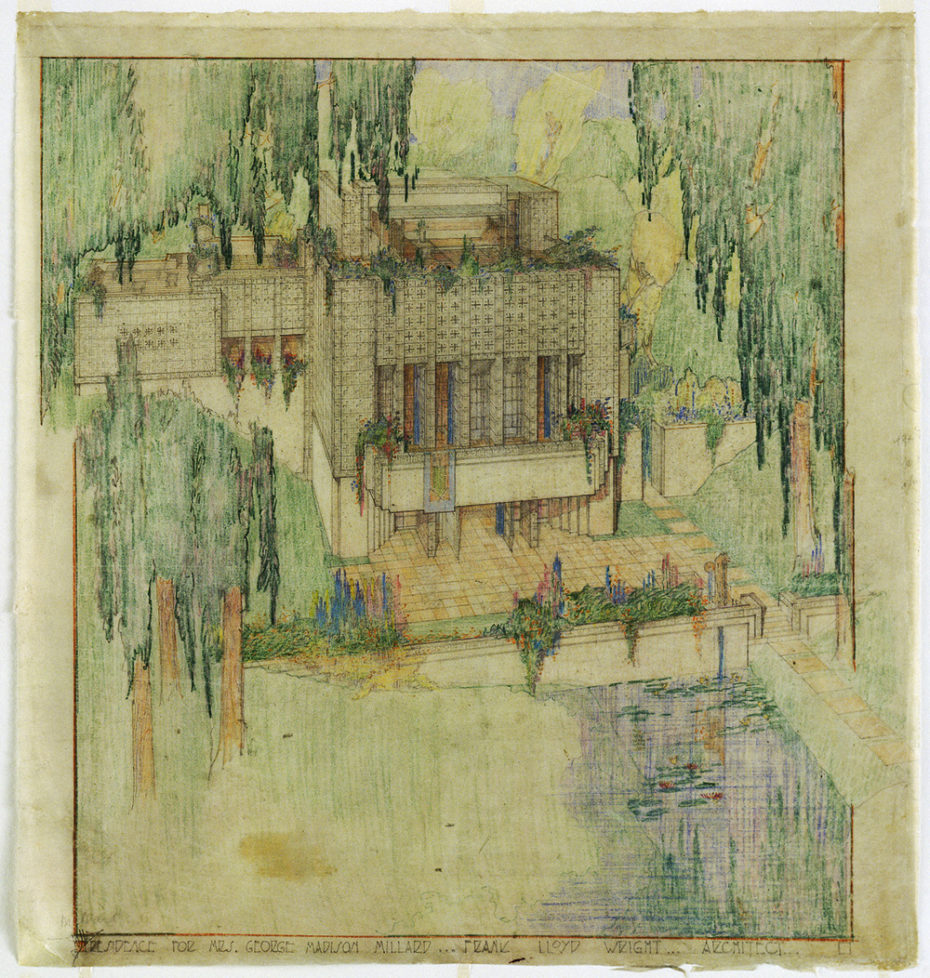

© Frank Lloyd Foundation

The massive Mayan structures of Frank Lloyd Wright look more like ancient tombs than homes, and represent a complete 180 in the architect’s career. For students of design, he’s untouchable; forever the cape-wearing dandy and Goliath of American architecture who imagined over 1,000 structures, including Manhattan’s Guggenheim Museum. But it took a while for historians to connect the dots, and realise that his often-overlooked Mayan Revival houses of the 1920s were manifestations of the ax murder of his beloved mistress…

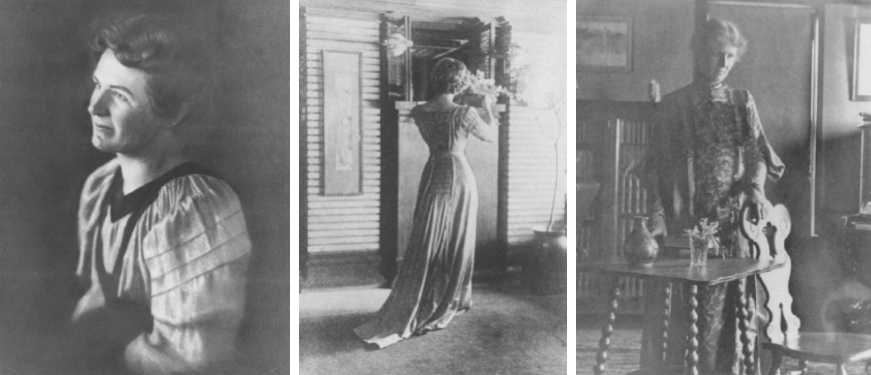

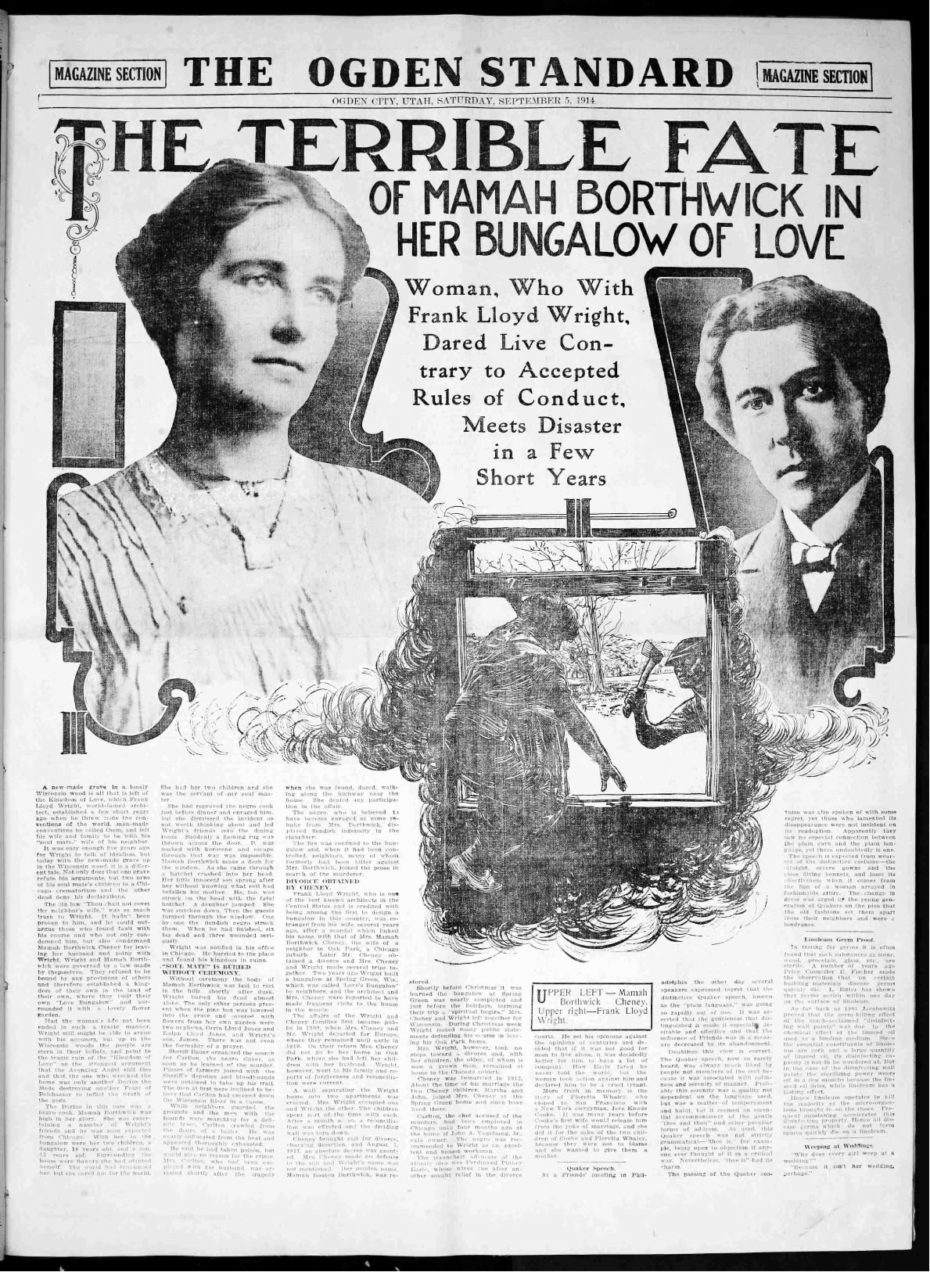

His mistress, Martha, wearing Frank’s own textile fashion designs

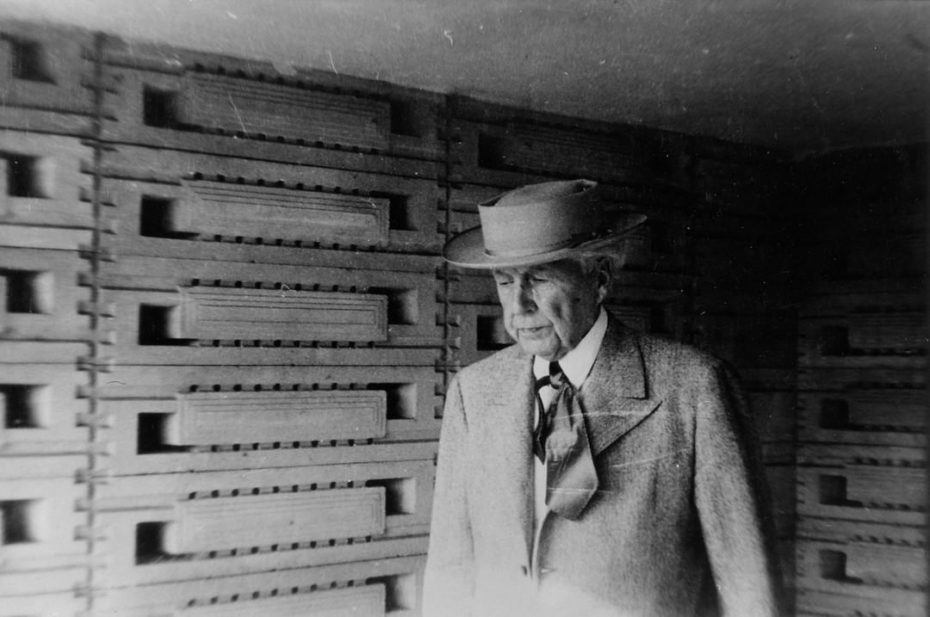

As Wright’s designs became more experimental at the dawn of the 20th century, it was around this time that his appearance and behaviour became a little more “colourful” too. He began to wear a red-lined cape, wear wide-brimmed hats and walk around with a cane. He even dabbled in fashion and textile design.

Frank Lloyd Wright

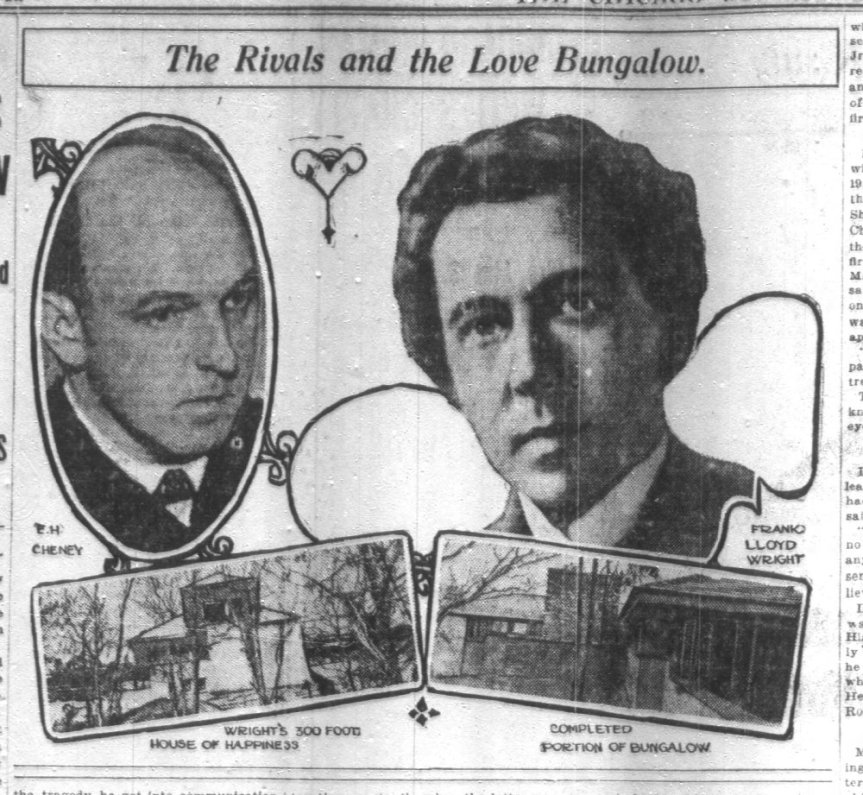

In 1904, Wright’s pioneering “prairie school style” homes, regarded as the antidote to the confined, closed-in architecture of the Victorian era, caught the eye of a Mr. Edward Cheney, who hired the architect to build a home for him and his wife, Martha (or “Mamah”). And that’s when the floodgates opened…

Mamah wasn’t like many women Wright had met. She was an intellectual, a feminist, and could hold her own with the intimidating architect. As Wright entered what seemed to be a midlife crisis, they began a passionate romance that scandalised both parties in the tabloids.

They were both married, both had kids, but both agreed that none of it mattered. They fled to Florence to draw up their own dream home: an ambitious estate they called “Taliesin,” (Welsh for “shining ground”) that was built on heritage land from Wright’s mother in Wisconsin.

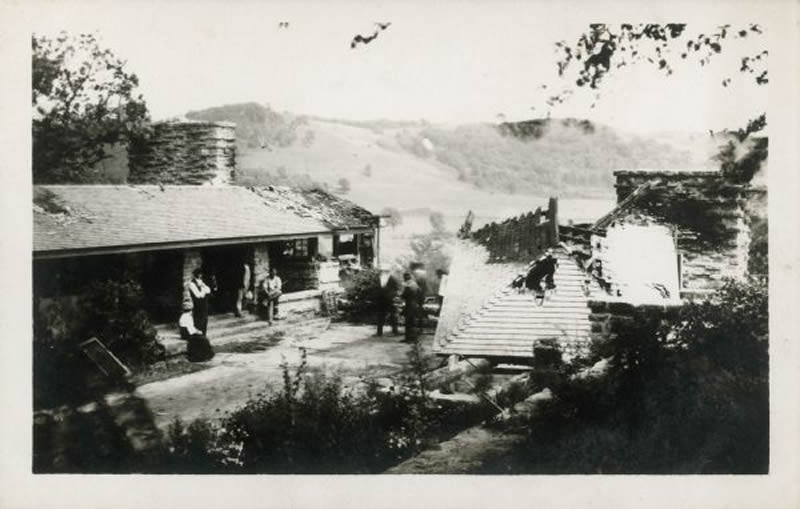

The house was completed in 1911, and doubled as a studio space for Wright. The building materials came mainly from the surrounding area, and it was truly a love letter from Wright to Mamah, who lived there peacefully until the unthinkable happened…

The couple’s cook, a man named Julian Carlton, started lingering in front of their window with a butcher knife (repeatedly). On August 15th, 1914, he was given his notice — but he wasn’t done with Wright and his entourage. That afternoon, Carlton drenched the house in gasoline and broke in to kill Wright and his entourage during lunch. He set fire to the home and murdered seven persons with an ax, including Mamah and her two children, before leaving Taliesin to burn:

Wright, however, happened to be out of town. When he came back, he was broken.

“All I had left to show for the struggle for freedom of the past,” he later wrote, “that had swept most of my former life away, had now been swept away.” To this day, the Taliesin massacre remains the greatest mass murder in Wisconsin history.

He buried Mamah with his own two hands, and then buried himself in his own work. Less than six months after the murders, Wright travelled to Southern California and visited the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego and its gallery of pre-Columbian architecture. It was at this time that something changed in him and began to reshape his own architecture.

Frank’s mid-1920s designs in California suddenly began looking more and more like Mesoamerican temples than groovy prairie pads of his past. “The walls are not so much covered with the Mayan patterns as [they are] made of them,” says LA Times journalist Christopher Hawthorne of Lloyd’s revivals. “They were places for Wright to bury the grief he’d been shouldering for nearly a decade, since Mamah Borthwick, the woman he’d abandoned his family and career for, was brutally murdered in 1914.

Franck Lloyd Wright Mayan revival sketch

La Miniatura, the Millard House in Pasadena, is the earliest in a series known as the “Textile Block houses”, designed by Wright in the 1920s. Their funereal character, Hawthorne believes, were the architect’s attempt “to put a definitive end to — to bury for good — a deeply troubled decade in his personal and professional lives”.

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

“The architect must be the master in the interior sense, not only of his tools, not only of his materials, but also of the human spirit. The soul of humanity is in his charge, really.”

Frank Lloyd Wright.

Frank’s Hollyhock House in 1927

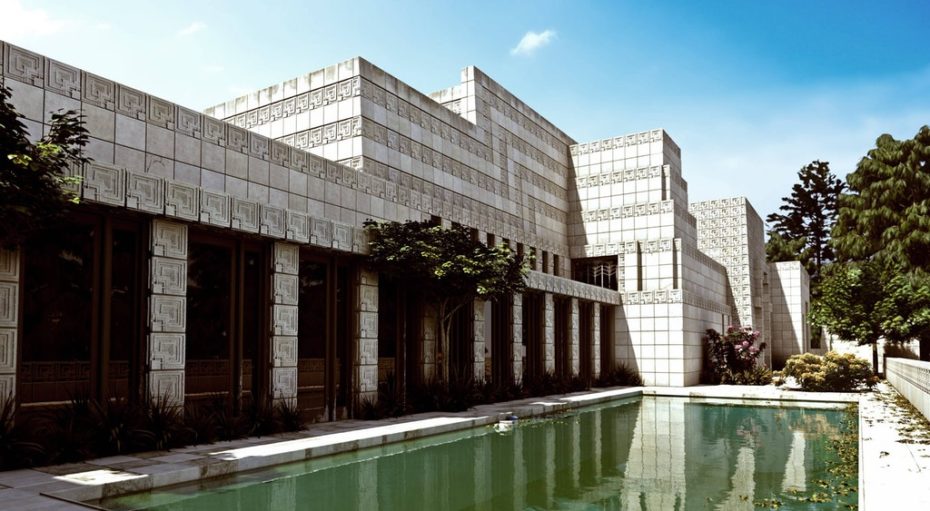

The largest, most emblematic and best-preserved of all Wright’s Mayans is unquestionably the 1924 house commissioned by Mabel Ennis in Los Feliz:

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

“It’s better suited to sheltering a Mayan god than an American family,” wrote critic Brendan Gill of the Ennis estate. It’s austere, concrete blocks were like nothing else in Los Angeles at the time (this was Spanish Revival heyday). “I don’t think I’ve ever come across a building quite as inscrutable, as strikingly mysterious as this one…What I remember more than anything is how much of a temple it seemed… even how crypt-like.” says Hawthorne about another of the pre-Colombian fortresses, the Millard House of Pasadena:

Milard House of Pasadena ©anna_lisa.sharar

In his autobiography, Wright wrote: “The concrete block? The cheapest (and ugliest) thing in the building world. . . . Why not see what could be done with that gutter-rat?”

The Hollywood movie industry immortalised Lloyd’s Mayan concrete houses on film as a lair for the mysteriously sordid and villainous…

The Los Feliz Mayan revival has played in everything from the mansion in “The House on Haunted Hill” in 1958 to Harrison Ford’s dystopian apartment in 1982’s “Blade Runner”.

Filmmakers recreated original elements of the Ennis House on sound stage sets or vaguely imitated these as in Predator 2 and several episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

Ennis House ©evdropkick

Exterior scenes of the house were shot on location for Blade Runner but interior of Deckard’s apartment was painstakingly recreated at Warner Brothers studios. David Lynch also used Ennis House for a few segments of the show Twin Peaks.

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

During these years, Wright and his assistants were living on a 1920s proto-hippy community in Taliesin, the tragic site of the murders that took place a decade earlier. Having returned and rebuilt it soon after the catastrophe, this had become his desert laboratory. The architect and his apprentices grew their own vegetables and made music together in the evenings. Frank would marry a bohemian clairvoyant and fantasist, with whom he had a volatile, drug-fuelled and erratic relationship. Soon after he fathered a child to a mystic dancer from Montenegro called Olgivanna, who would eventually be his third wife. In 1925, tragedy struck yet again however at Taliesin when an electrical a fire burnt the house to the ground, sparing the lives of its occupants but destroying Wright’s art collection, valued at around half a million dollars.

Sowden House © Elizabeth Daniels via Curbed

In need of work again, a year later, Wright’s son, who was also an architect and seemed to have inherited his father’s taste for the temple like structures, completed the enigmatic Sowden House. It’s been called “cultic”, nicknamed the “Jaws house,” and in recent years it even gained a new, much darker notoriety—as the alleged murderous lair of the Black Dahlia’s killer.

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

The name, Frank Lloyd Wright, and architecture has, for many Americans, become synonymous. But how many of us know the darker side to the most famous architect in American history? His private life was as unforgettable as his architecture and deeply intertwined; unfit for American families and the perfect place to take shelter from one’s inner demons. And if you’re wondering why you’ve never heard about the details of Wright’s personal life? Well, tales of ax murders generally don’t help sell houses.