Gustave Eiffel, the Michelin brothers, the Peugeot family– they were all educated by one of the oldest, most prestigious universities in France– which no longer exists. In its heyday, this ‘Harvard of Paris’ was housed in an extraordinary 17th century Parisian mansion, one that if you’ve been to Paris, you’re most likely very well-acquainted with. You see, I happened upon an album of photographs in the archives of the French National Library, which allows us a glimpse through the windows of perhaps the grandest école in French history. I’d never heard of this École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, but as I began looking closer at the architecture, I realised I’d been here before! Déjà-vu indeed, for these are the same walls of the famous Picasso Museum in Paris, one of the city’s most visited cultural attractions today. And unbeknownst to thousands of tourists that pass through its grand portals, this mansion once nurtured some of the greatest minds in Europe as they examined rare minerals in the attic and tinkered with test tubes where Cubist masterpieces are now hanging for the public…

A tenant of this Parisian palace during the height of the Belle Epoque, the university’s graduates were known as the “Centraliens”, who over generations, went on to become the country’s greatest architects, engineers and CEO’s at some of the world’s largest fortune 500 companies.

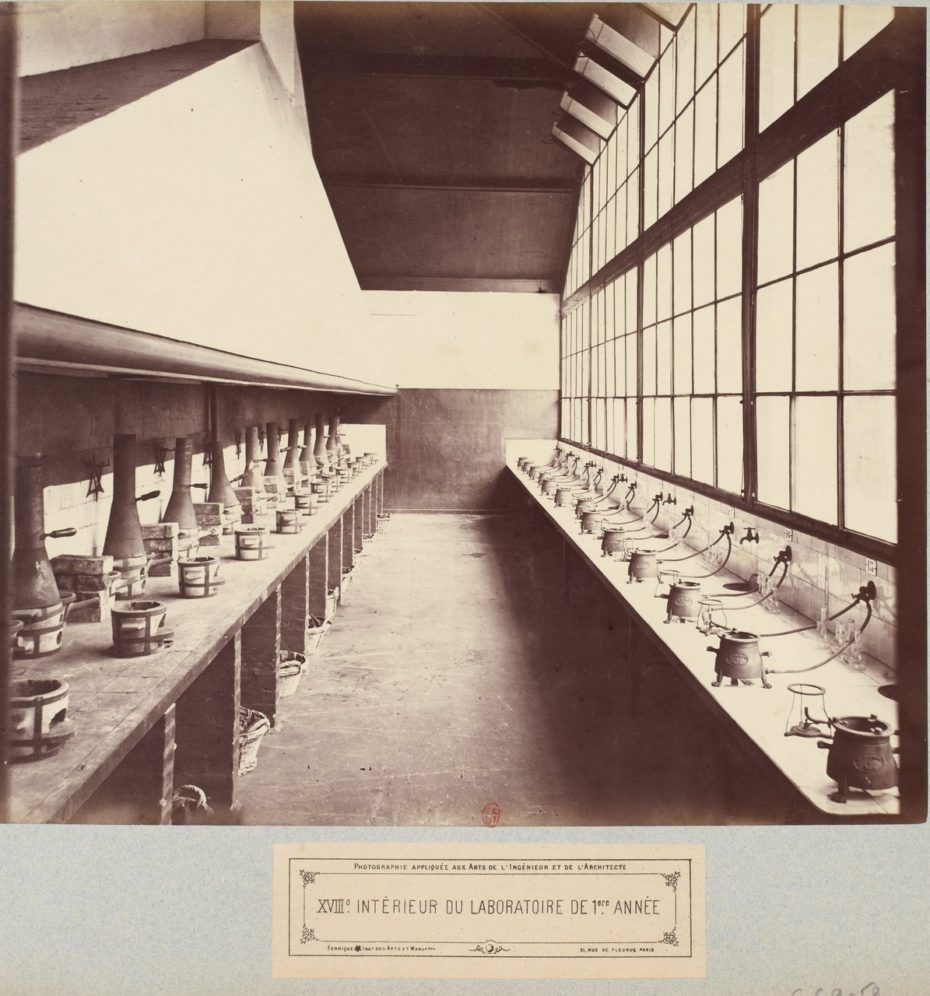

When the school was founded, the steam engine was in its infancy, and first year students were nicknamed the “pistons”, alluding to the mechanical components that essentially powered the steam engine. This grande école had partnerships with the world’s most powerful institutions, including Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Oxford University, Cornell, Dartmouth, Berkeley and the University of Chicago to name a few.

In 1921, the school made history by enrolling its first female students, opening its doors to two teenage pioneers who dreamed of a higher education and a career in engineering; a path virtually unheard of for women prior to the Great War.

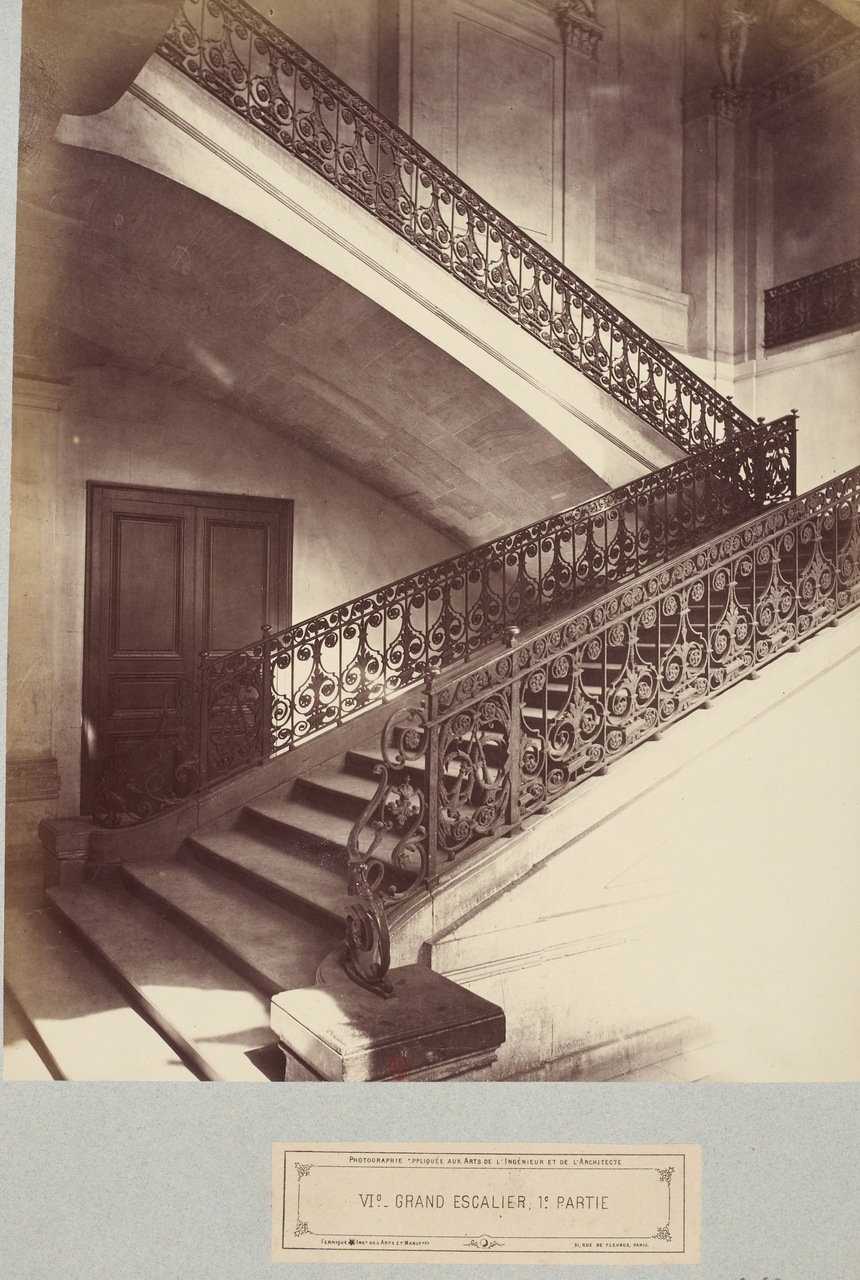

Today, the existence of the Central School of Arts & Manufacturing (École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures) amidst these grand staircases and immense halls, has long been forgotten. Over 185 years after its foundation in 1829, this grand institution of engineering was permanently dissolved into a wider education network to boost international competitiveness as recently as 2015.

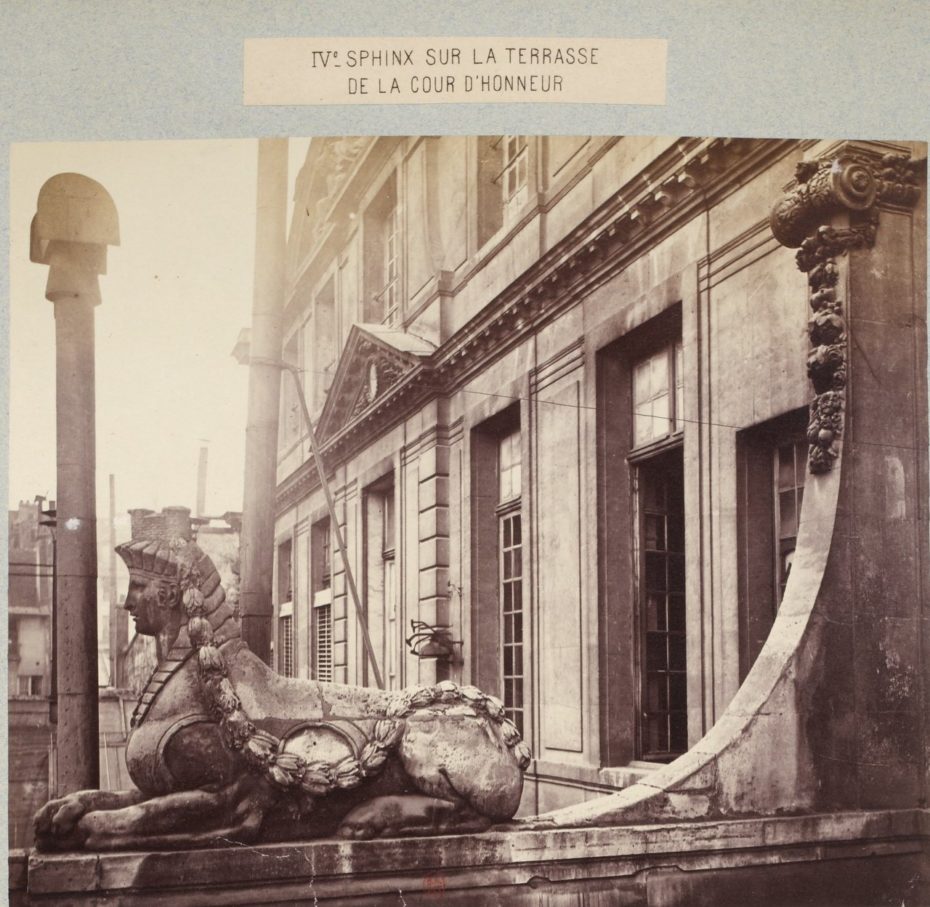

The 17th century palace was built in 1659 by Pierre Aubert, protégé to the architect of Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte. The building’s creator and tenant also happened to be the King’s collector of gabelle, a very unpopular tax on salt that existed in France for nearly six centuries until the 1940s. So in case anyone was wondering why the Picasso Museum is housed in a building called the Hôtel Salé (the salty hotel)– now you know why.

Over the centuries, the hôtel particulier (aka. a grand townhouse) had many tenants. It was rented to the King of Venice as his embassy in the 16th century, before being looted and serving as the “national literary deposit” during the French Revolution to store and inventory priceless books discovered in the local convents. But it was during the height of the Industrial Revolution that our ‘Harvard’ of Paris occupied the site in the historic Marais district, until it was eventually moved further up the Seine to a considerably less glitzy.

After some years in limbo, the city of Paris bought the mansion in the 1960s. Following the death of Picasso in 1973, the artist’s descendants had handed over a large portion of his works to the French government in lieu of paying inheritance tax, and by 1985, the collection was complete and the museum was born.

Was the bourgeois palace-turned-cabinet of curiosities suited for Picasso?

“The museum’s 17th-century home, the Hôtel Salé, in the historic Marais district, with its garden, courtyard and two-story, sculpture-encrusted entrance hall, has never been ideal for showing art,” wrote The New York Times upon the re-opening of Musée Picasso after a lengthy renovation period in in 2014. “The interior is choppy, with smallish spaces, dead ends, and illogical connections.”

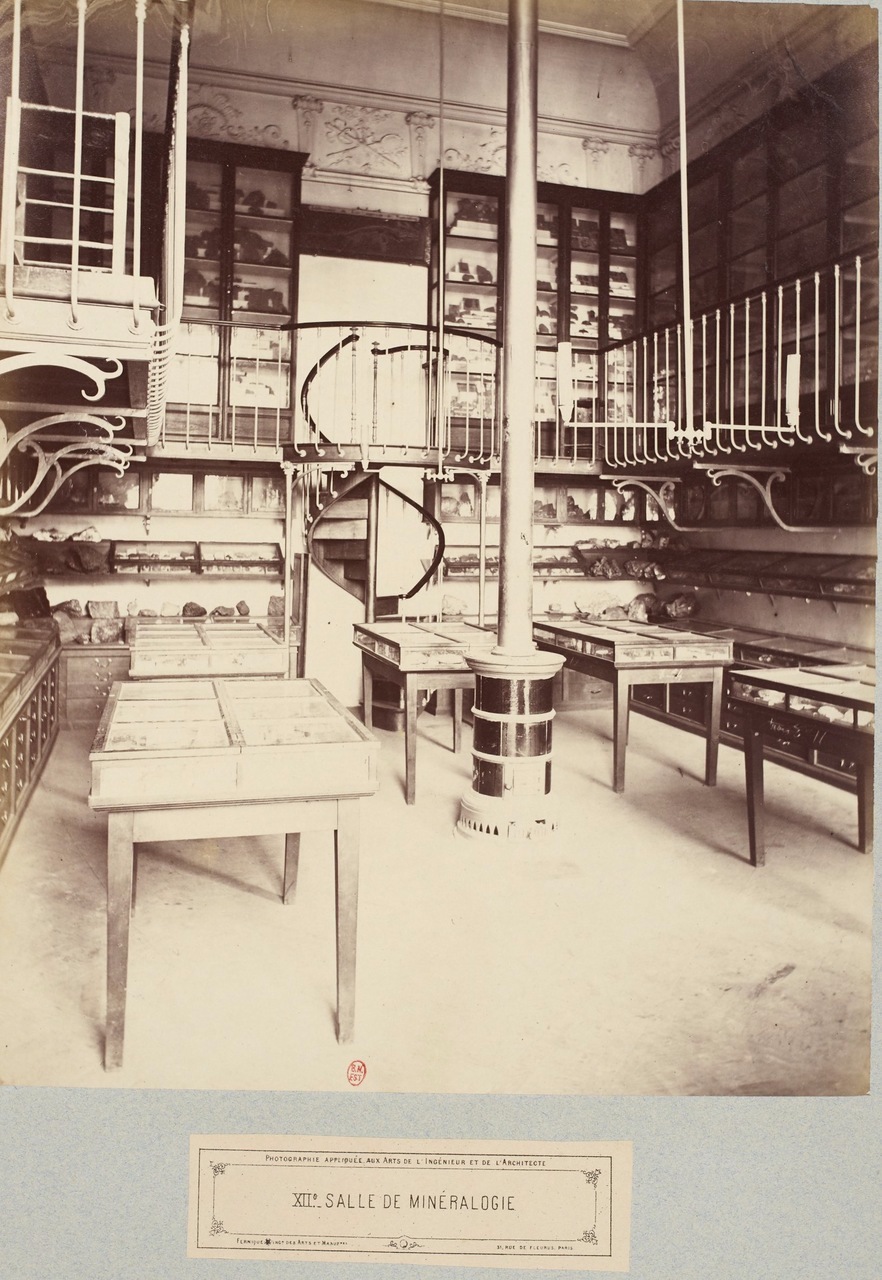

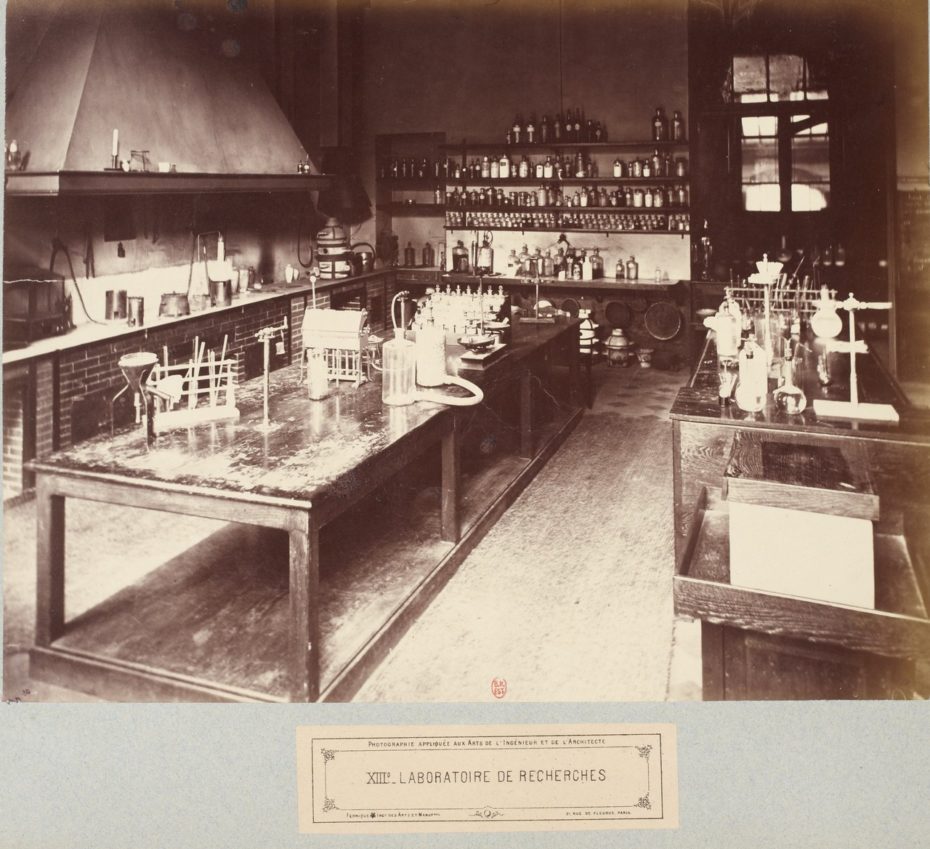

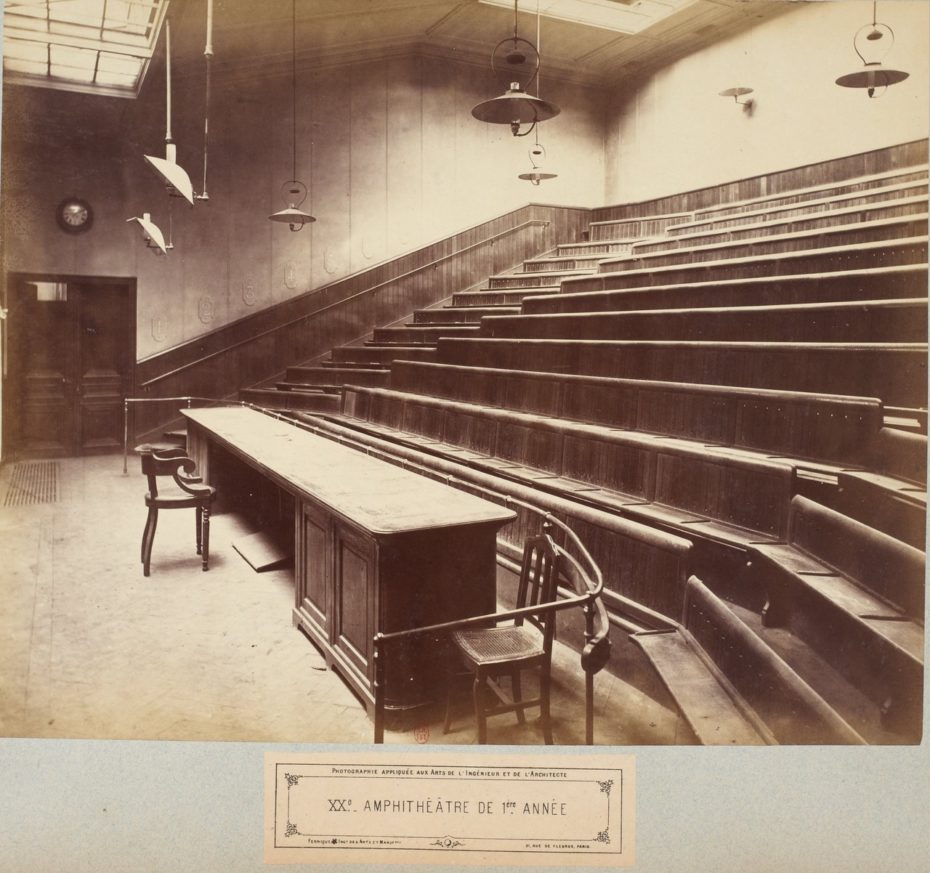

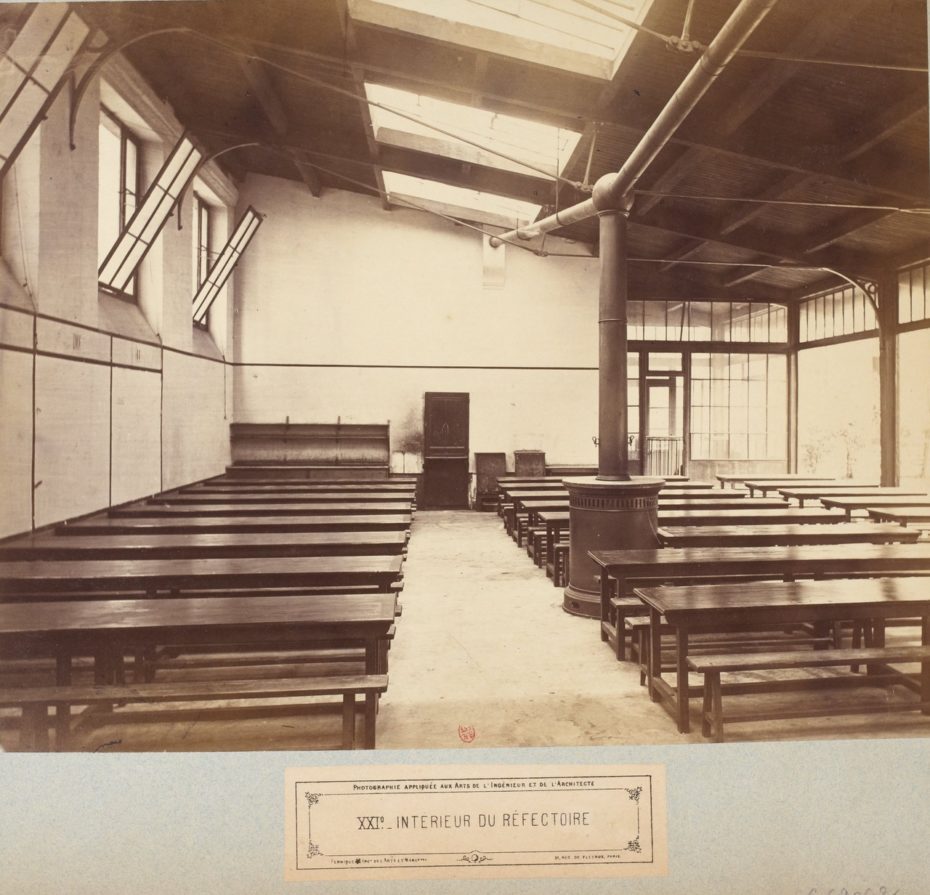

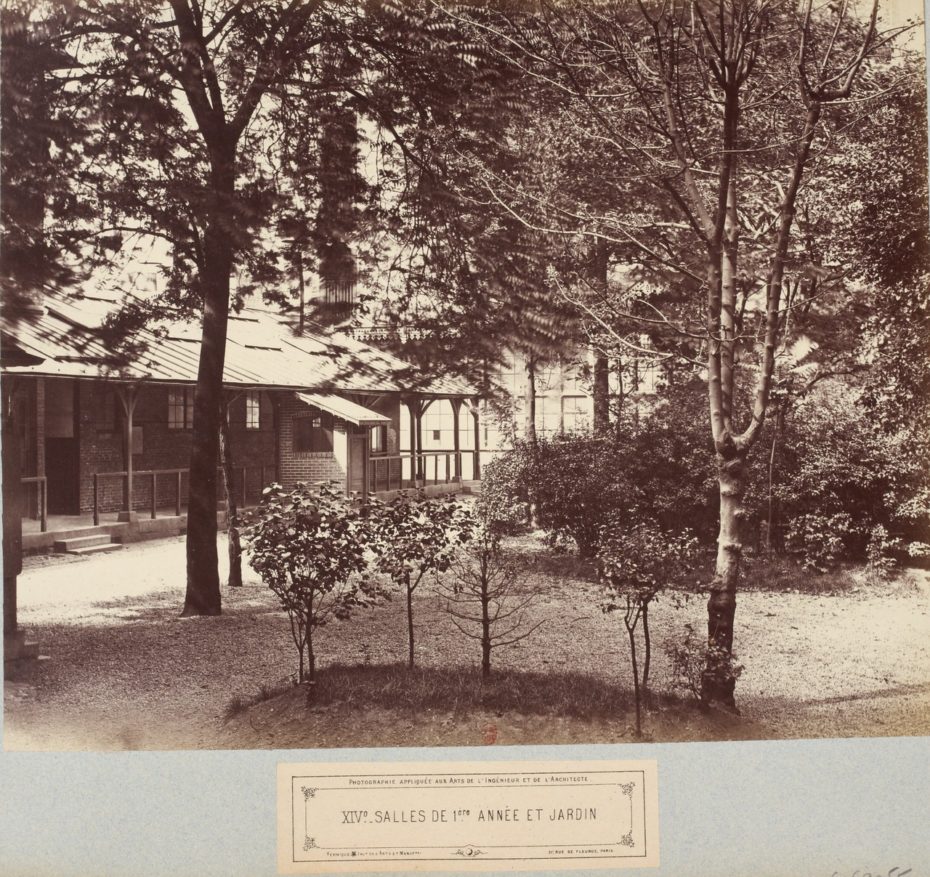

Nothing remains of the school’s footprint at the Hotel Salé, which is what I find makes these photographs so special, tucked away in the archives of the National Library. The laboratories and lecture halls where the likes of Gustave Eiffel mastered his métier; the collections and various courtyard outbuildings where students once huddled around the era’s most important thinkers; have all vanished from the site, as if they were never there.

If you want to get a feel for what might have been there, the closest you’ll get is of course the historic lecture halls of the famous Sorbonne University, but you’d need a hall pass for that. Alternatively, I’d recommend paying a visit to one of Paris’ least-known museums, a jewel box of curiosities called the Musée de Minéralogie. As you’ve seen in the first photograph of this article, the engineering school at the Hôtel Salé once housed its own mineralogy museum on the top floor– and I wouldn’t be surprised if much of the same collection is now housed in the antique wooden cabinets of this little museum, within the Luxembourg gardens.

And while you’re sitting on the café terrace of Musée de Picasso this summer, having just completed a dizzying art tour, remember that you’ve seen this building as a not many other museum visitors have…

Archive photographs (public domain) courtesy of the French National Library.

Hungry for more Paris? The updated edition of Don’t Be a Tourist in Paris is now available. Or become a MessyNessy Keyholder to gain access to our Travel eBook library and a direct line to our Keyholder Travel Concierge to plan your perfect trip. Need help planning a weekend in France? Need some restaurant recommendations for a remote village in the North Pole? We’re here to help.