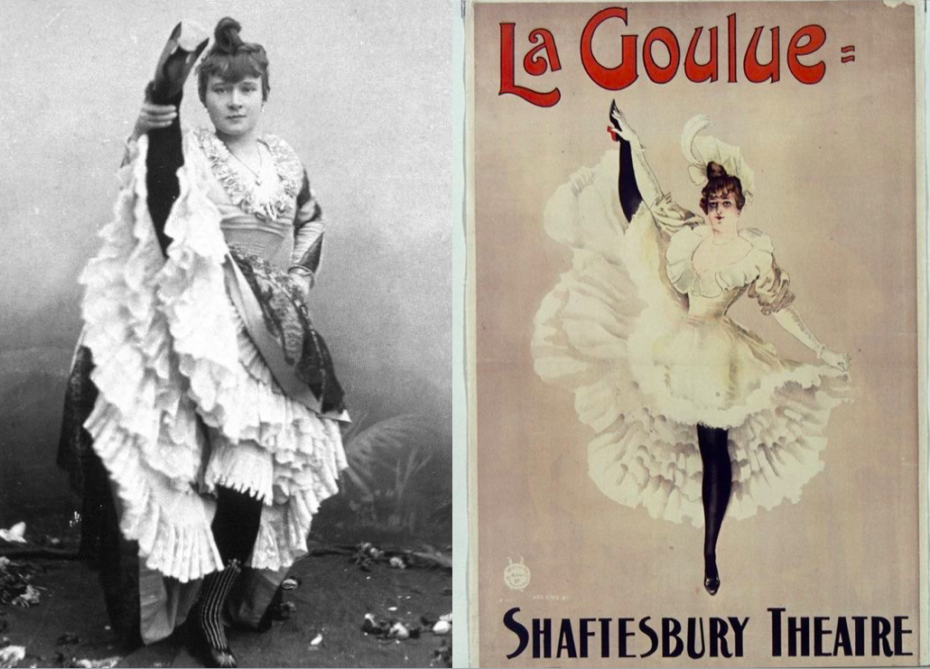

The world knew her as la Goulue — literally, “the Glutton” — because her appetite for mischief was bar-none in Belle Epoque Paris. It was a nickname she earned in high-kicks and unmatched can-can skills, but it was won at a high price. Today, her rise to the top as “the Queen of Montmartre” has become a legendary, albeit cautionary tale of the glory days at the Moulin Rouge, as well the fickle nature of fame. So let’s trace her footsteps across the 18th arrondissement of Paris, shall we?

Before she was la Goulue, she was simply Louise Weber: a girl from Alsace who liked to play dress-up in the lacey delicates of her mother’s laundro-mat clients. By her teens they’d relocated to Paris, where she’d graduating to sneaking out in their borrowed gowns to get her first taste of cabaret life.

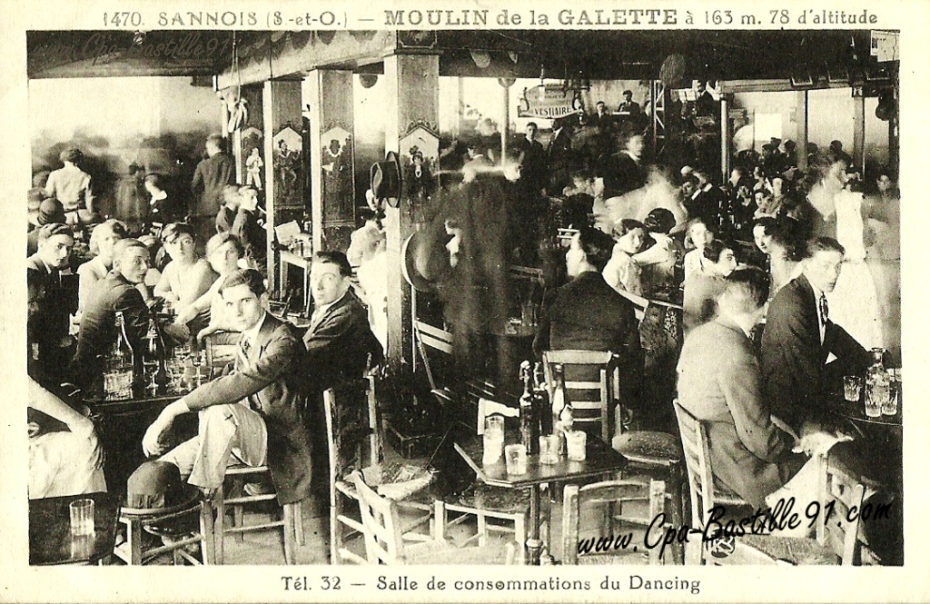

She first honed her dancing chops at le Moulin de la Galette (which is still in business as a restaurant today) and began doing the rounds at small clubs in Pigalle, quickly becaming a popular personality.

As a guest performer at venues such as Pigalle’s Elysée de Montmartre, she was invited to do the equivalent of today’s celebrity club appearances: get free drinks, and charm everyone’s socks off. In a rapidly expanding city where dancers were becoming a dime-a-dozen, the fact that la Goulue stood out from the crowd was a true testament to her charisma…

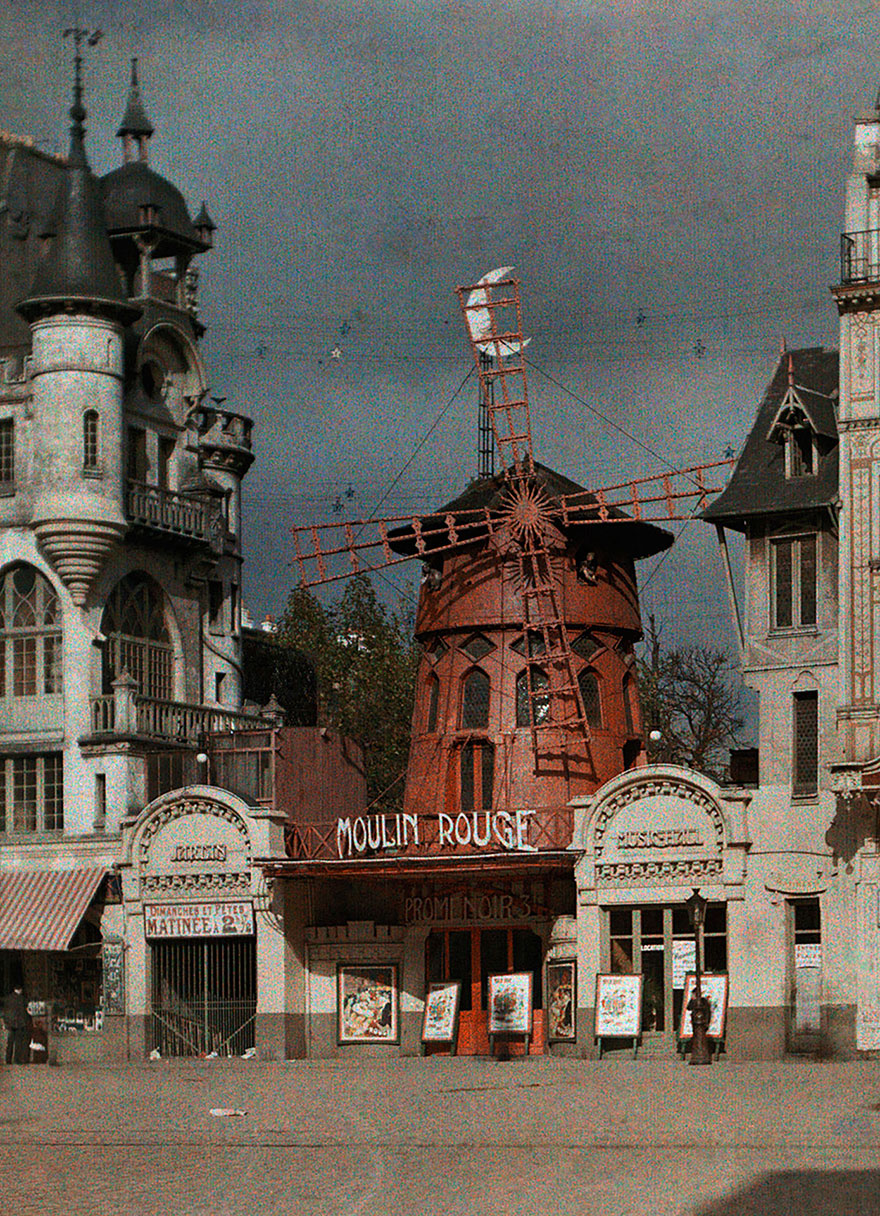

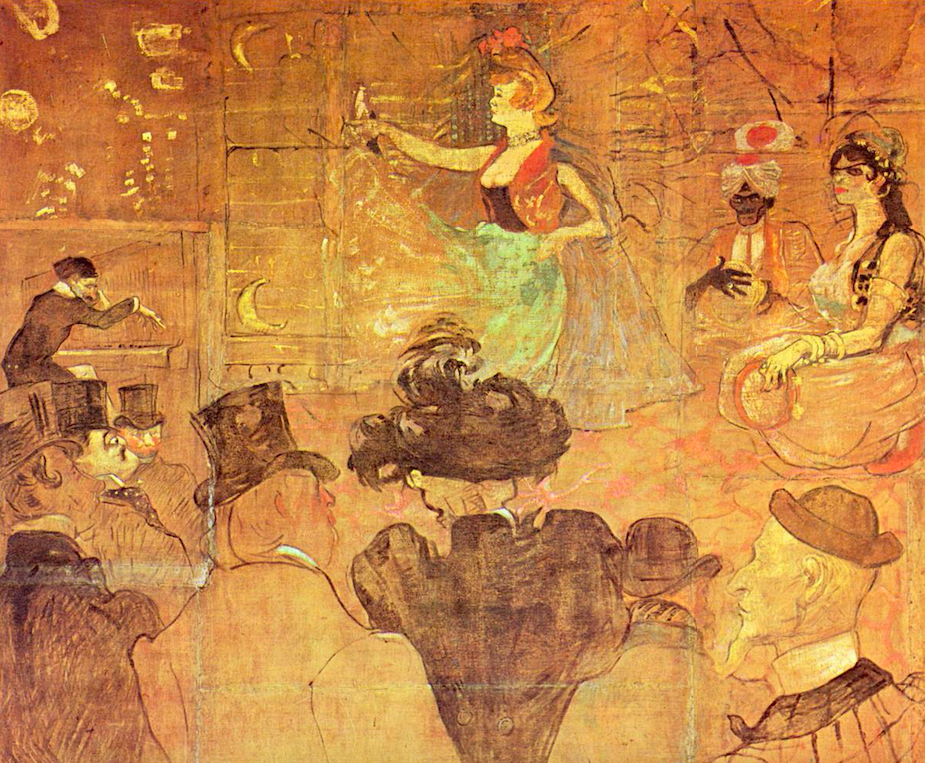

Her success that night earned her a first gig at the Moulin Rouge, which was determined to one-up the Elysée as the first ever electrically lit dance-hall, with clientele of everyone from conmen to princes.

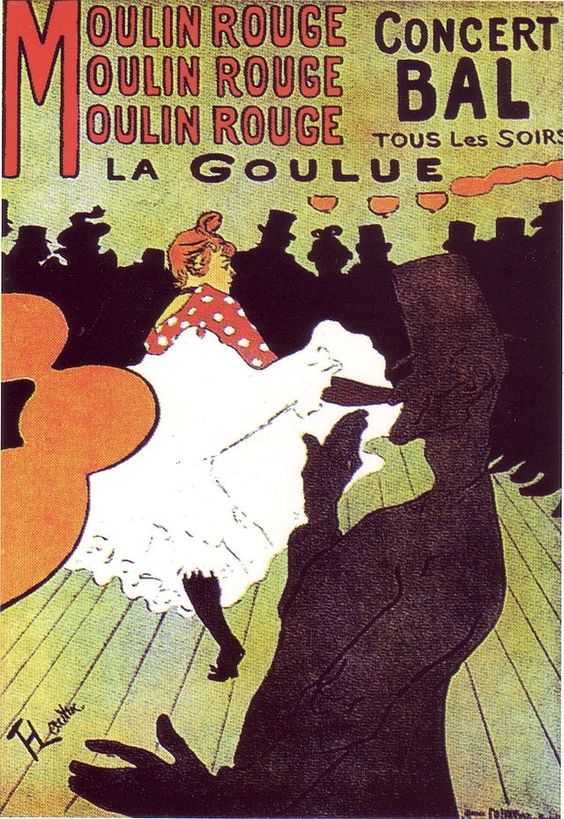

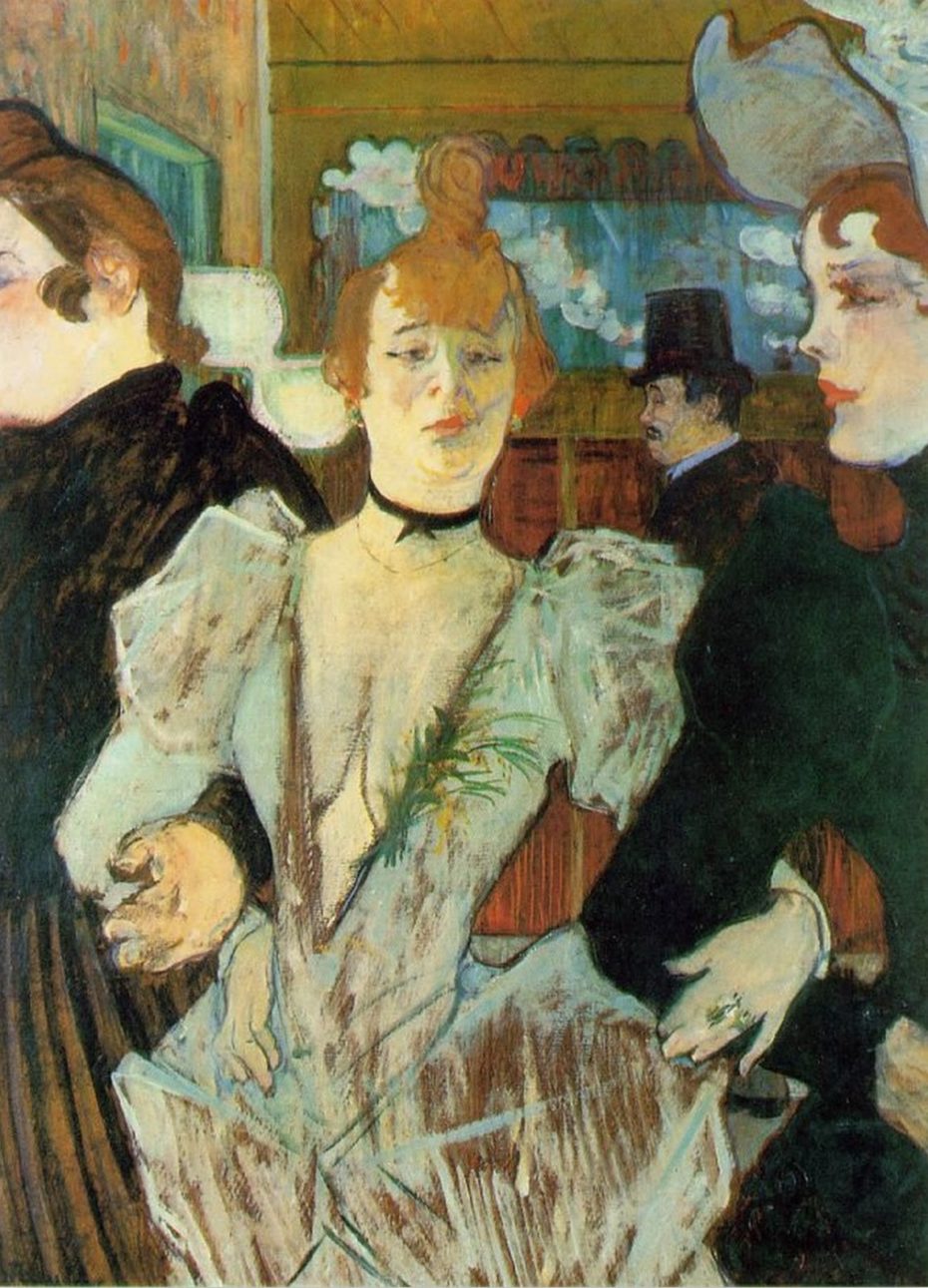

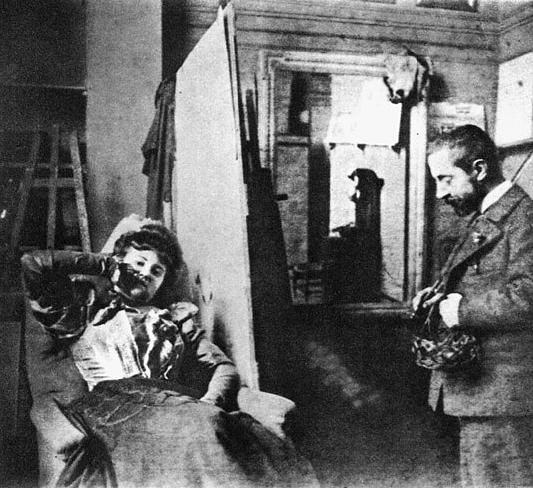

It was the future of cabaret, and Weber (literally) made the perfect poster-child thanks to Toulouse Lautrec. When the Moulin Rouge cabaret opened, Toulouse-Lautrec was commissioned to produce a series of posters. The artist, who was always holed up at one of its dark tables, quickly found a muse, drinking partner, and lifelong friend in Weber; no other dancer was knocking off gentlemen’s top-hats with a single high kick, or showing glimpses of their heart-stitched panties — at least, not like Weber, whose audacious energy was captured in one of Lautrec’s many drawings of her…

Toulouse-Lautrec immortalized her in his portraits and posters of her dancing at the Moulin Rouge.

At this point in her career, she was the toast of Paris and the highest paid entertainer of the day. Few ladies of her time enjoyed the independence and freedom Weber did, years before women had the right to vote. She’d been booked as a permanent headliner at the Moulin Rouge, and thanks to her frequent habit of picking up a customer’s glass and quickly downing its contents while dancing past their table, she’d earned her affectionate nickname “la goulue” (the glutton).

But the excess of the Belle Epoque had a pendulum effect for Weber, who was either on top of the world or drinking her weight in absinthe in a lifestyle that was burning a little too brightly. “You had the gramophone, electricity, and these cabarets,” says a historian François Reynaert, “Paris was a place of joy, but also distraction. The working class was growing, but their rights weren’t evolving.”

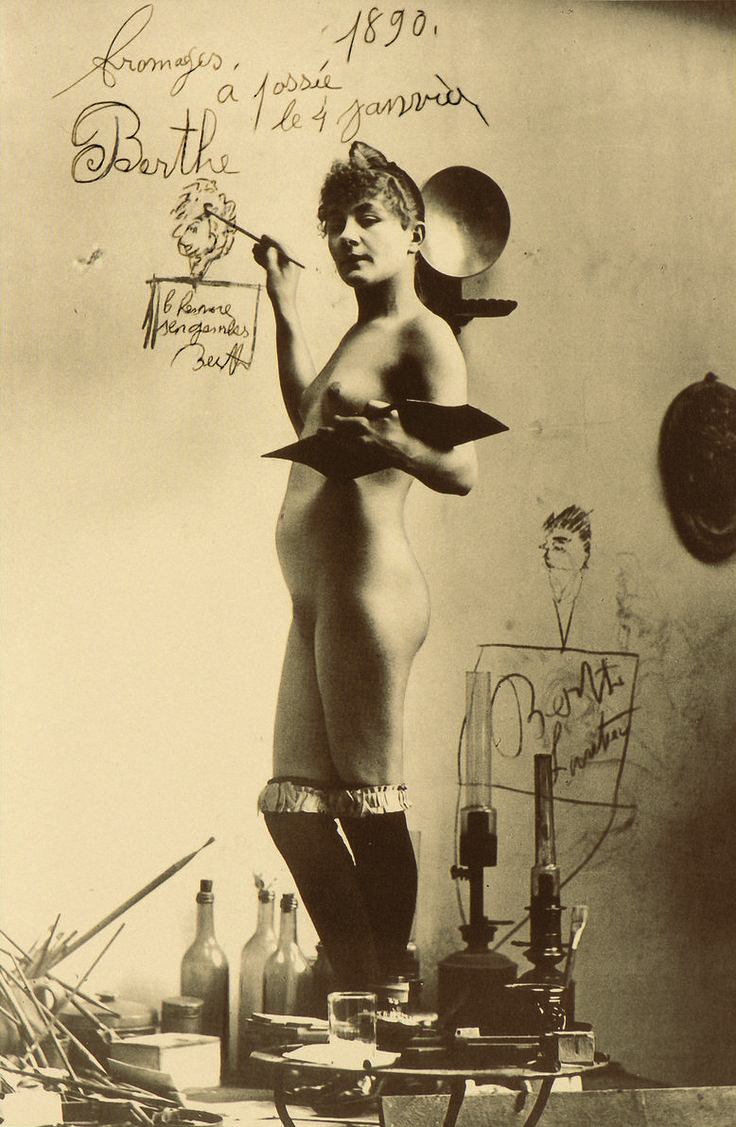

Eventually. she met the Montmartre painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who introduced her to a group of models who earned extra money posing for the community’s artists and photographers. Achille Delmaet would later find fame as the photographer who had taken many nude photographs of la Goulue.

Aside from Weber’s love of dance, there was always another, more frightening motivating factor: succeed on the stage, or you’ll be sent the streets. “As the daughter of a blanchisseuse (laundry woman),” explains Reynaert, “that would’ve been her path.”

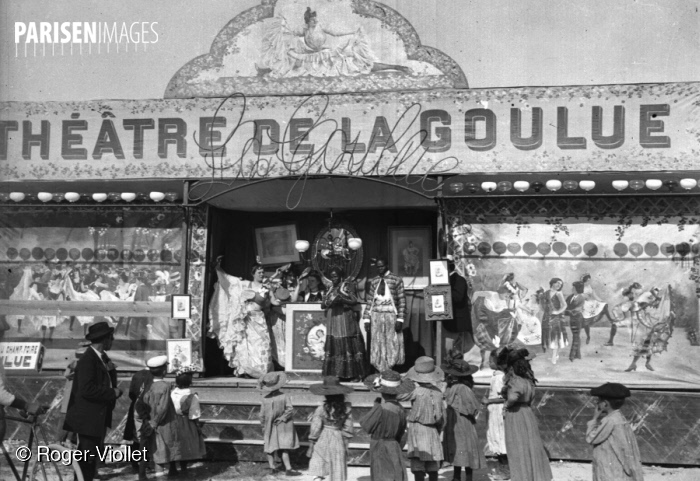

By her late 20s, Weber’s health started to wilt. She’d arrive late and fussy to rehearsals with her pet goat in tow. The boiling point was a brawl with another dancer, Aicha, planned at midnight on the bridge over Montmartre’s cemetery in which Weber would have fallen to her death if a pedestrian hadn’t caught her. Furious, she decided to leave the dance hall behind — but la Goulue without the Moulin Rouge had little appeal for spectators.

Her celebrity crumbled almost overnight, and her alcoholism consumed her much as it did the glory days of the Moulin Rouge, which “were really only a period of five years,” says Reynaert, “at the end of the 19th century. After that, the best party scene gradually moved to Montparnasse.”

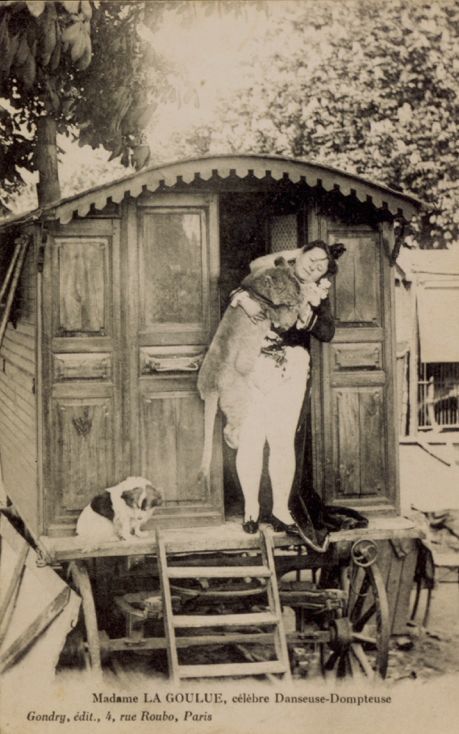

And the fallen Weber? She could be found taming lions in her failed circus act, or selling flowers and cigarettes on the streets of Pigalle. If she made headlines, it was almost always in mockery.

Come the late 1920s, a journalist “couldn’t believe his eyes” when he saw an elderly Goulue emerge from a caravan in the flea market of Sainte-Ouen to give him a dance. To this day, it’s the only footage we have of the woman who took Paris by storm, and the up-turned hem of her can-can skirt…

Pssst! Step into the shoes of La Goulue this summer and stay overnight in the iconic Moulin Rouge Windmill!