Note: Some of the images below contain disturbing content.

Alphonse Bertillon was bad at a lot of things, but excellent at two: solving crime, and pissing people off. Both were honed during his long career at the Prefecture de Police in mid-19th century Paris, one of the grisliest eras for tracking down criminals in the rapidly growing metropolis.

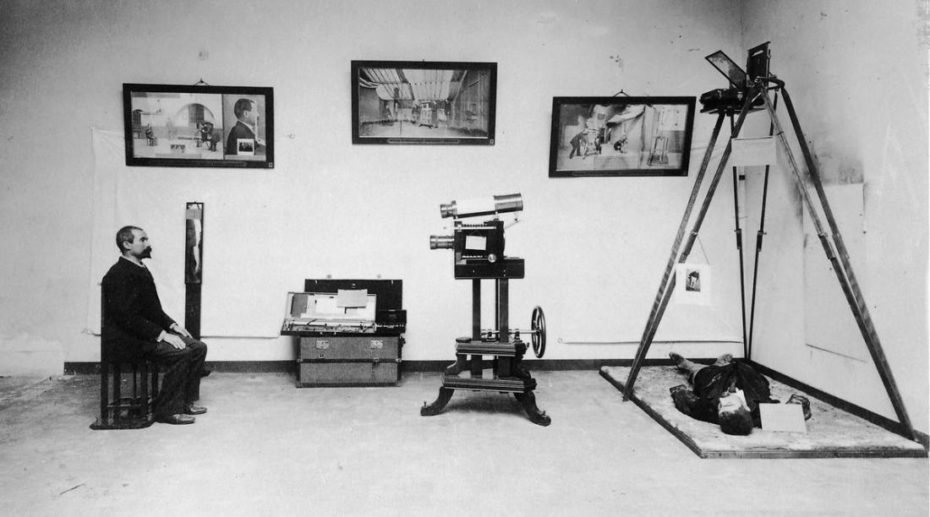

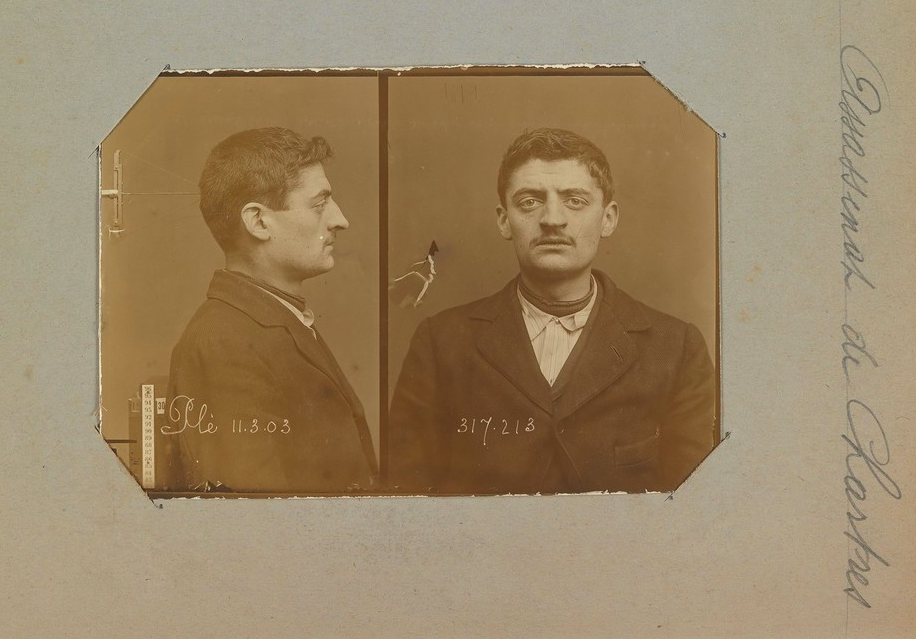

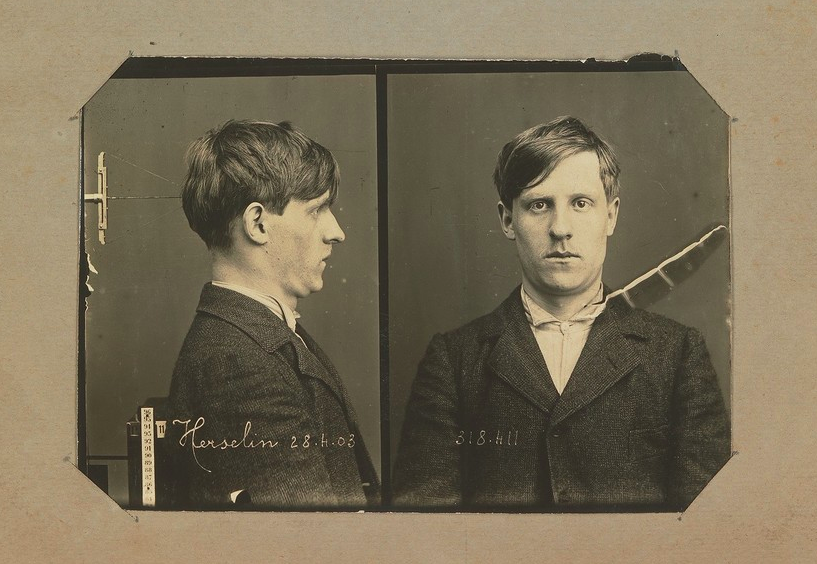

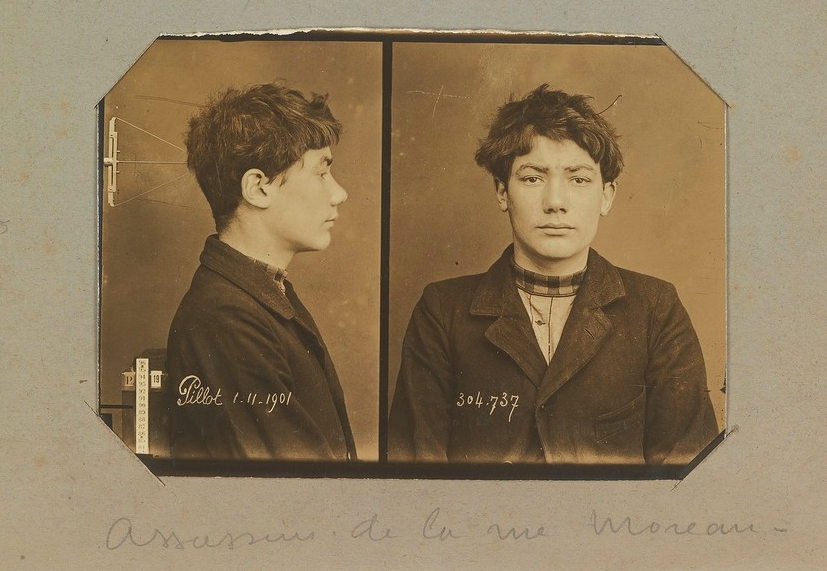

Bertillon, who dropped out of school and started off as a lowly copyist at the Prefecture, relied on wits and grit alone to prove himself to his colleagues. He was the first forensics scientist to use photography as a tool for decrypting murder sites, and the inventor of the mug shot (for which he was his own best guinea pig, as evidenced above).

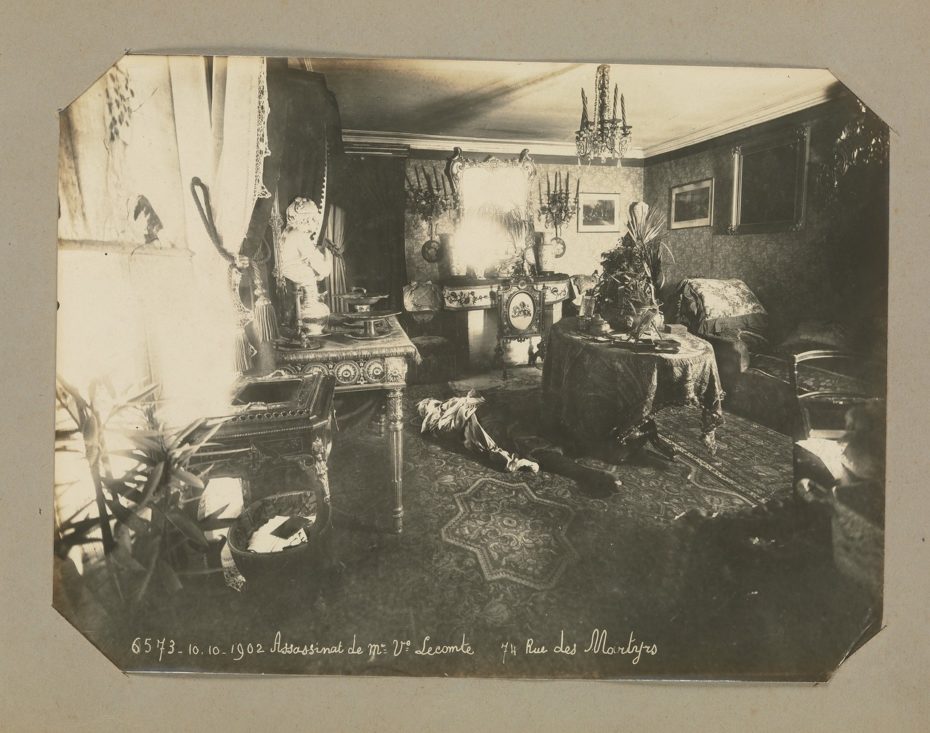

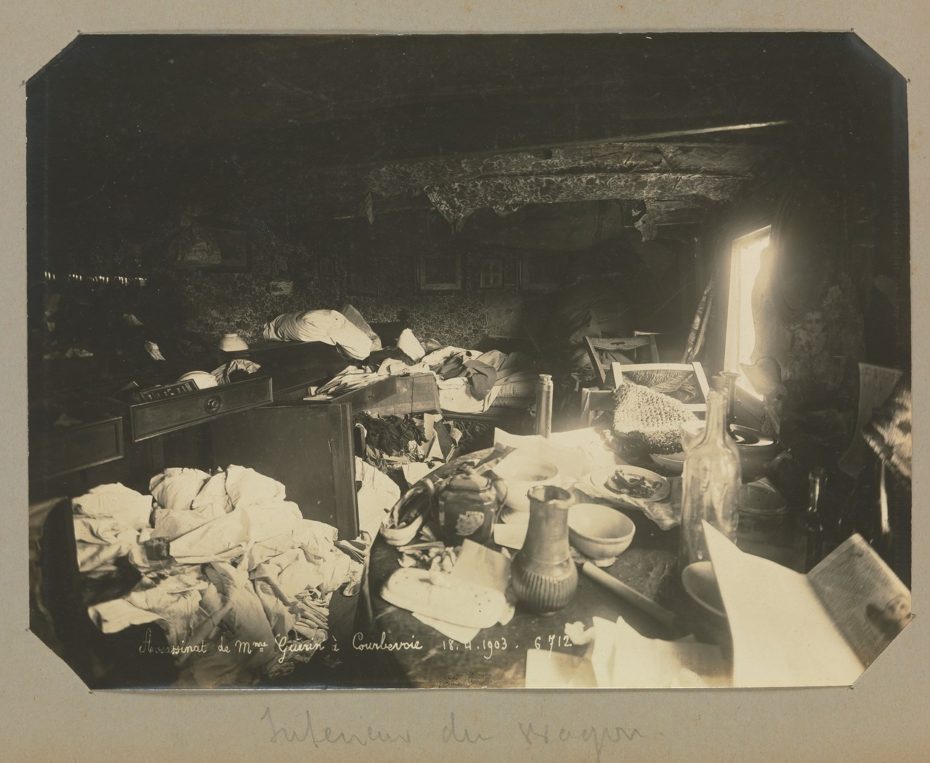

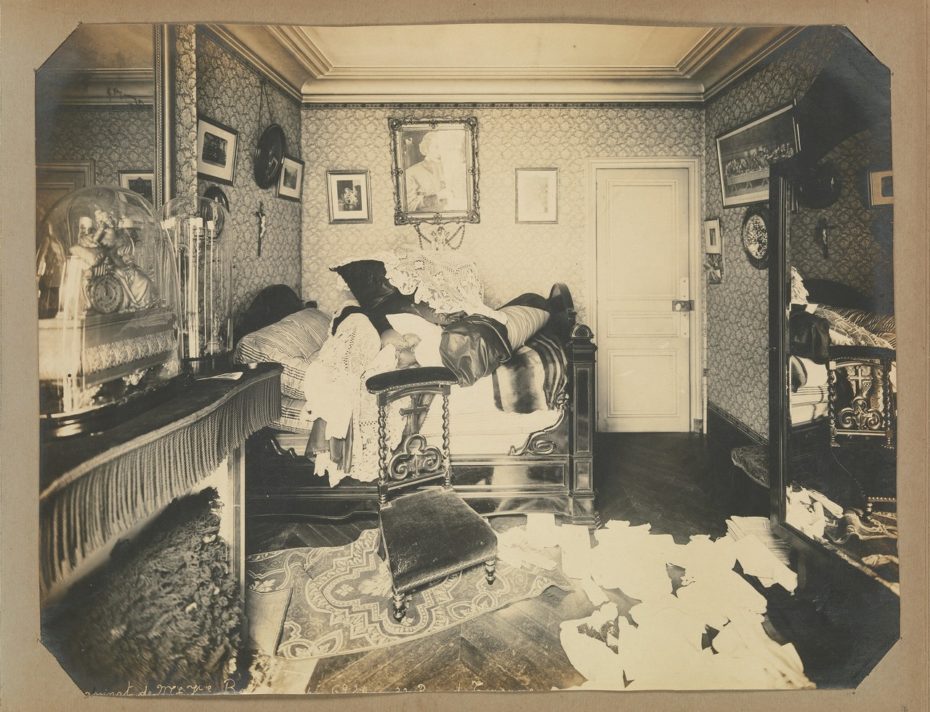

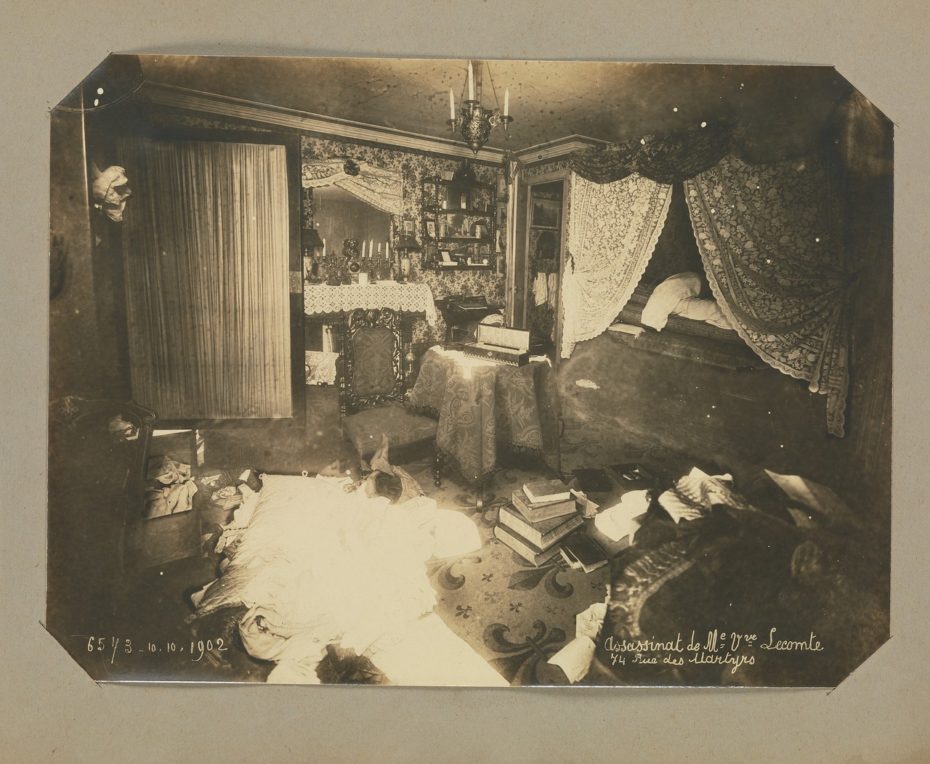

Bertillon believed a crime scene photo could speak volumes about the evils taking place on its premises, and called his new practice, “an acoustic survey”. A dusting off of his case album today makes for a mesmerising, albeit disturbing window into Paris’ past…

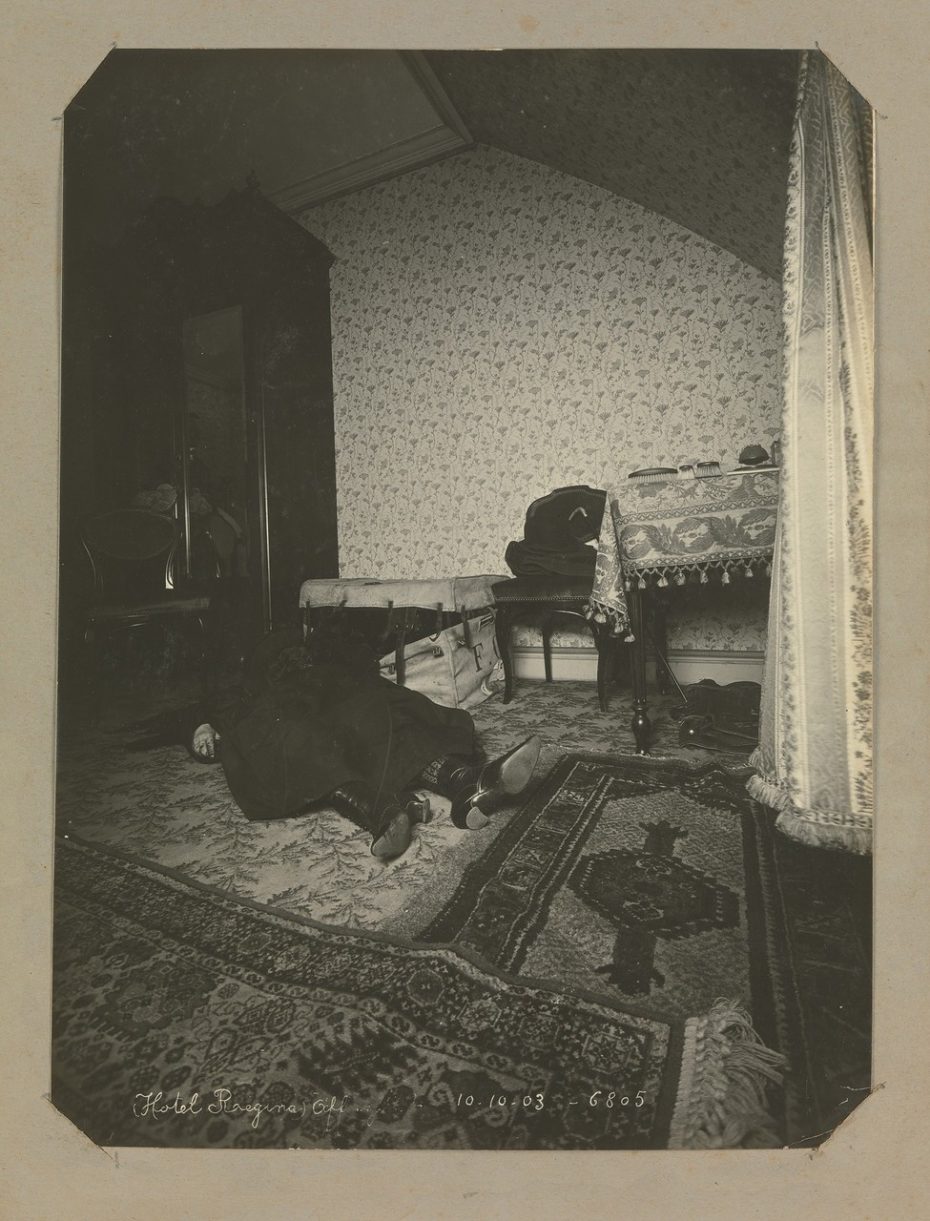

It goes without saying that the scenes, with or without traces of bloodshed, are horrific. Murder just seems to leave a haunting stain on the snapshots, that can’t be washed out with time — even when its only witness is an empty street:

Then there are the glaringly unhinged snapshots, in which every fallen vase and torn sheet tells a story…

Bertillon’s cards were stacked against him in his youth. He dropped out of high school and joined the army, but was discharged in 1875. When his father found him an entry-level gig at the Police Department, it was a chance to prove himself.

France was also trying to pick itself up by its bootstraps after the devastating Franco-German war, a huge economic crash, and the social-fabric-unraveling Paris Commune.

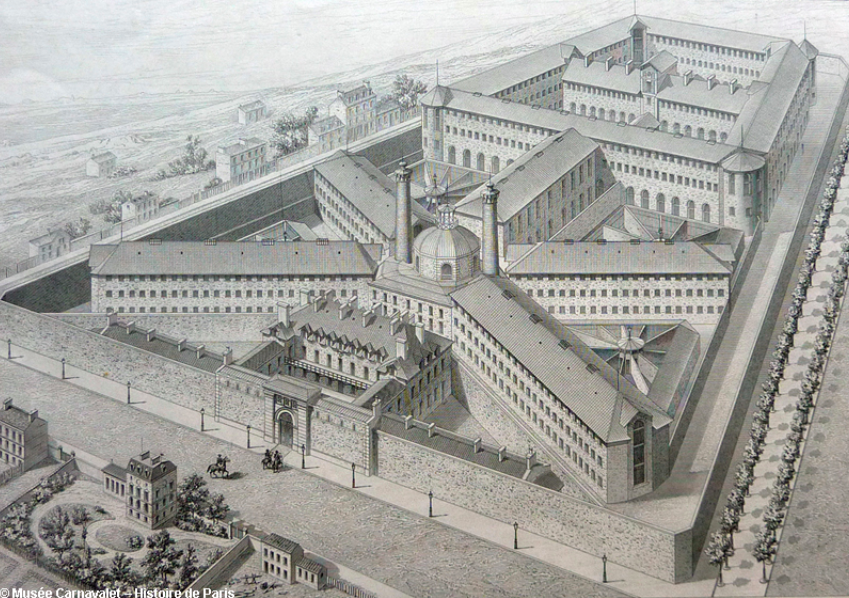

Crime was through the roof, and Bertillon was tired of seeing the same offenders getting dragged in, so he toiled away in secret on his own criminal recognition system at the new La Santé Prison, much to the frustration of his superiors. Today, La Santé Prison is still one of the country’s most infamously secretive, and brutal prisons:

An aerial shot of the prison today shows that it’s every bit the goliath that its antique drawings depict. Weaselling in and out of its premises was a feat within itself for Bertillon:

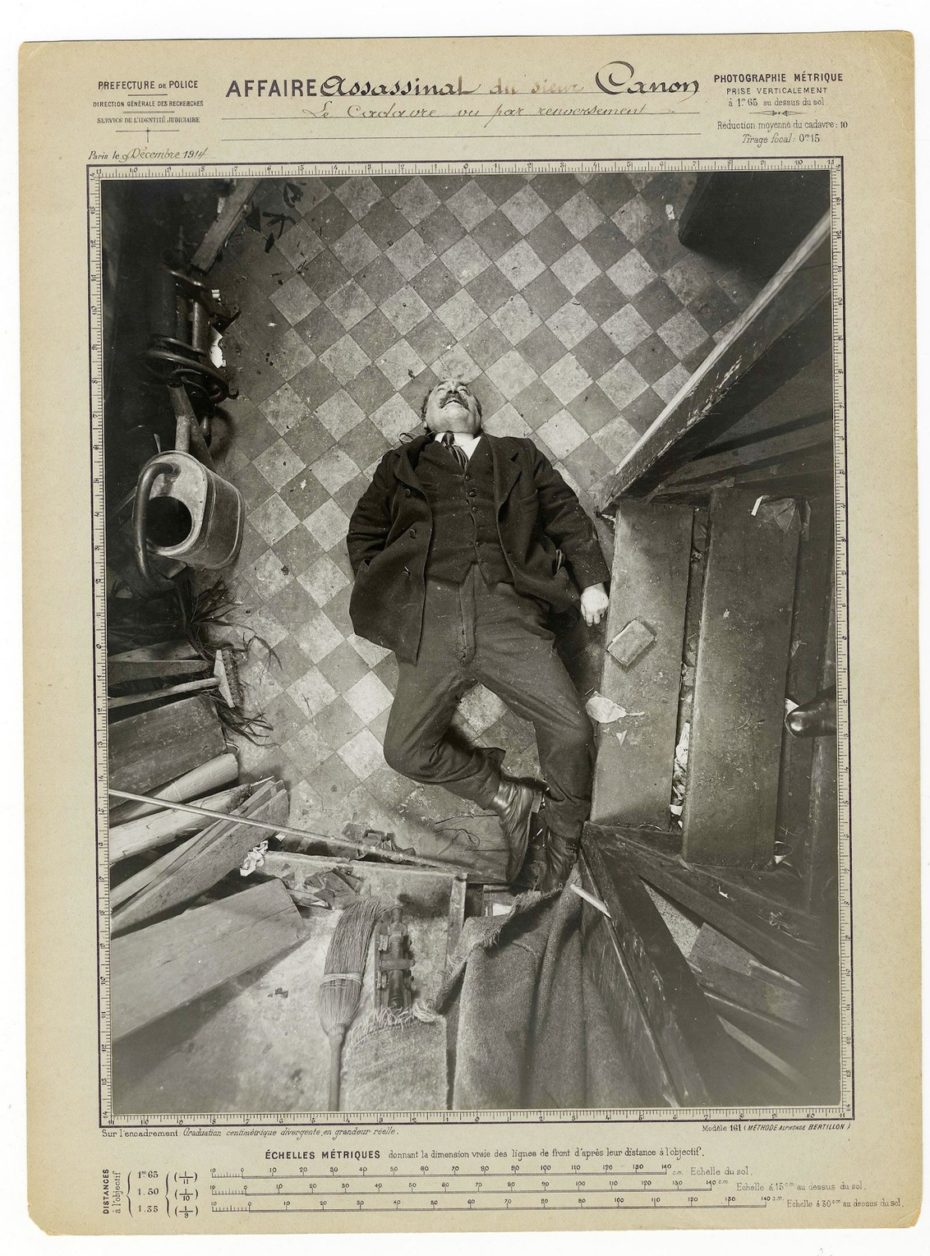

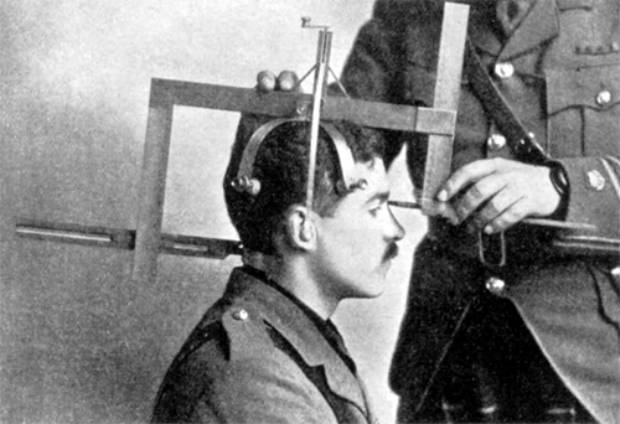

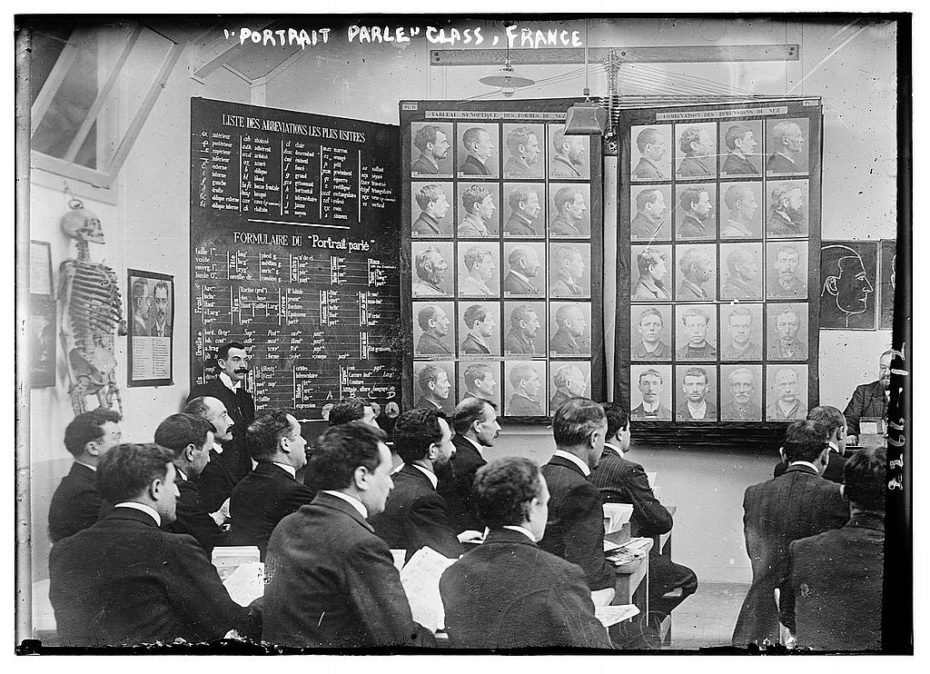

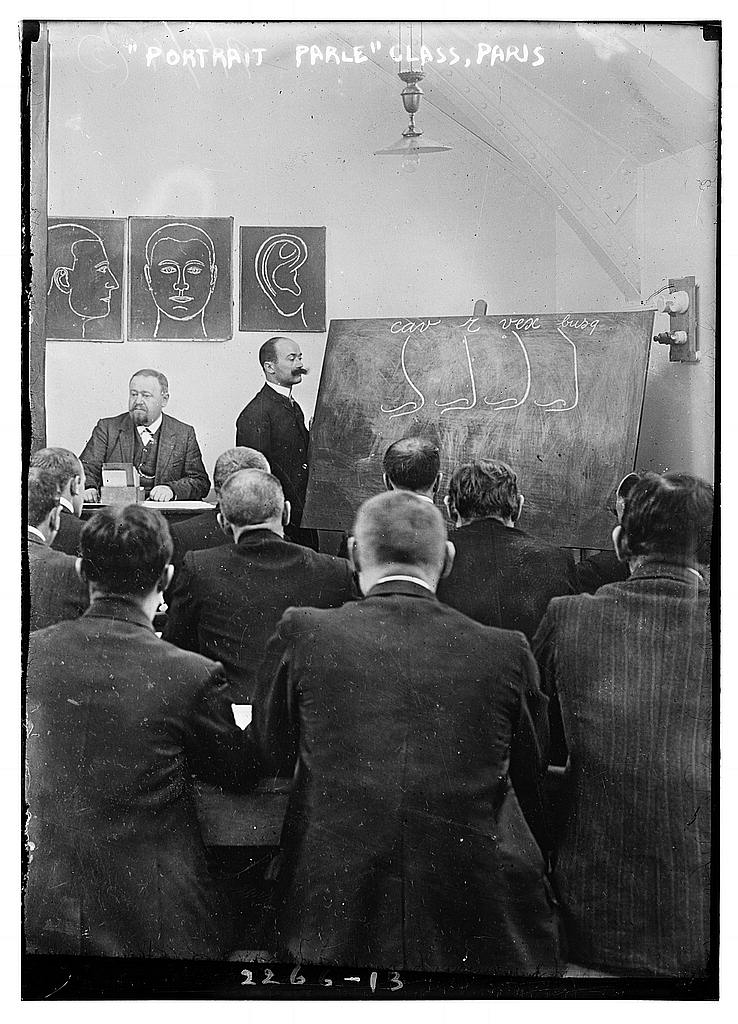

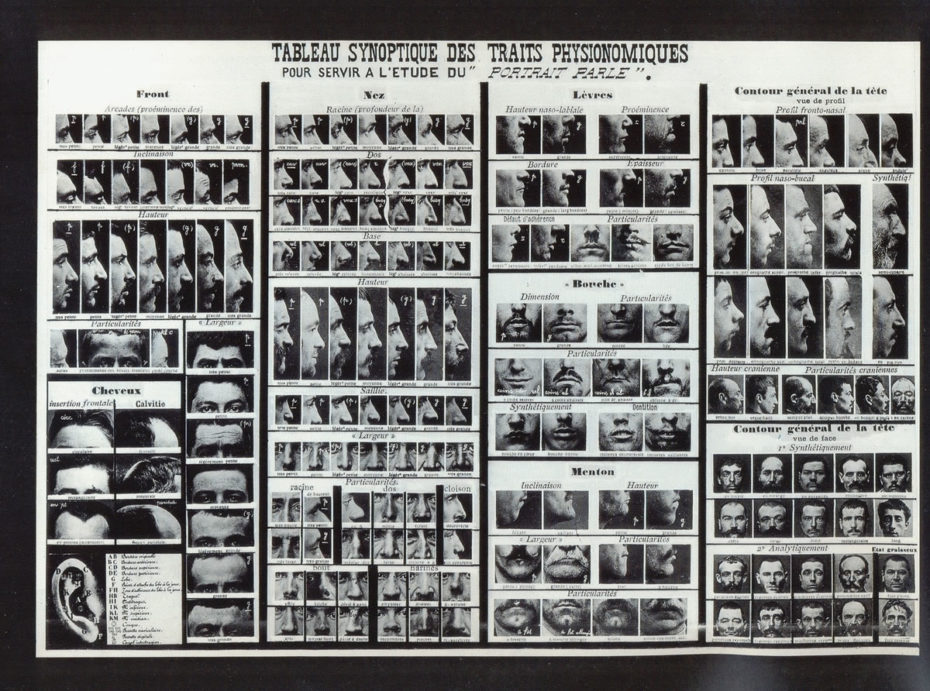

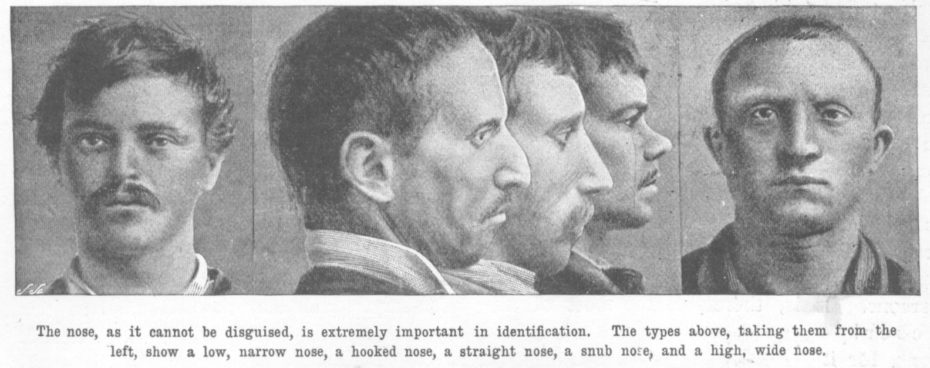

The idea was to measure offender’s bodies and study their features, creating a kind of anthropometric “criminal” standard.

It did help France capture 241 recidivists, but such physical profiling had inherently disturbing undertones; the nefarious cliché of being “a born criminal” was a direct byproduct of the Bertillon System.

He measured things like the length and width of a person’s head, middle finger, and left foot, which is precisely why mugshots became so key to his practice. The cadaver in the photo below shows Bertillon’s first moves towards the standardisation of the practice:

The Bertillon System was far from perfect, but it did create a sense of unprecedented categorisation. You can imagine how strange it must have been to be amongst the very first humans to get their mug shot snapped, especially during a time when photography itself felt a bit like science fiction…

Such impeccable attention to detail sealed his fate in history as the only man, wrote Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, whose services could possibly be more in-demand than his own fictitious sleuth; “To the man of precisely scientific mind,” he says, “the work of Monsieur Bertillon must always appeal strongly.”

A Paris Crime Museum of Note

The morbidity continues at a century-old little museum run by the French police, inside a police station in the Latin Quarter of Paris. Two thousand objects evoke the history of crime in Paris, including glass-encased murder weapons with suspicious stains, a gruesome archive of police photography, and even skeletal remains. La Musée de la Préfecture de Police is open everyday from 9am-5pm. (4 rue de la Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, 5ème).

Hungry for more Paris? The updated edition of Don’t Be a Tourist in Paris is now available.Or become a MessyNessy Keyholder to gain access to our Travel eBook library and a direct line to our Keyholder Travel Concierge to plan your perfect trip. Need help planning a weekend in France? Need some restaurant recommendations for a remote village in the North Pole? We’re here to help.