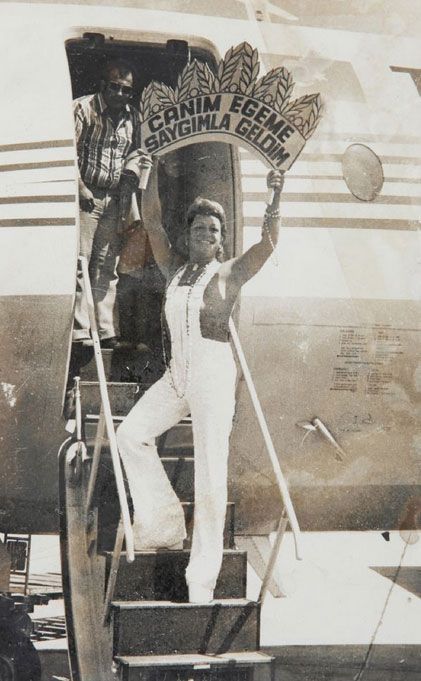

It’s 1977, and Mick Jagger is sitting down for an intimate dinner in the port city of Bodrum, Turkey. He’s vacationing on the coast with Atlantic Records president Ahmet Ertegun, and about to meet the evening’s final — and most anticipated — guest: Turkey’s bedazzled, belly-dancing answer to Liberace; a man whose platform heels paved the way for everyone from Bowie to the Spice Girls: Zeki Müren.

The 20th century actor, singer, and poet became a cultural icon in Turkey not only for the queer community, but anyone who’d ever felt fabulously different. “Müren [told him] that he was going to teach Frank Sinatra [his song] “alaturca” on his USA trip in ’63,”says pop historian Murat Meriç. But for whatever reason it never happened, so “he taught Jagger instead” that night. Müren may not have made a name for himself in America, but to those in the industry, the clarity and range of his voice was bar none.

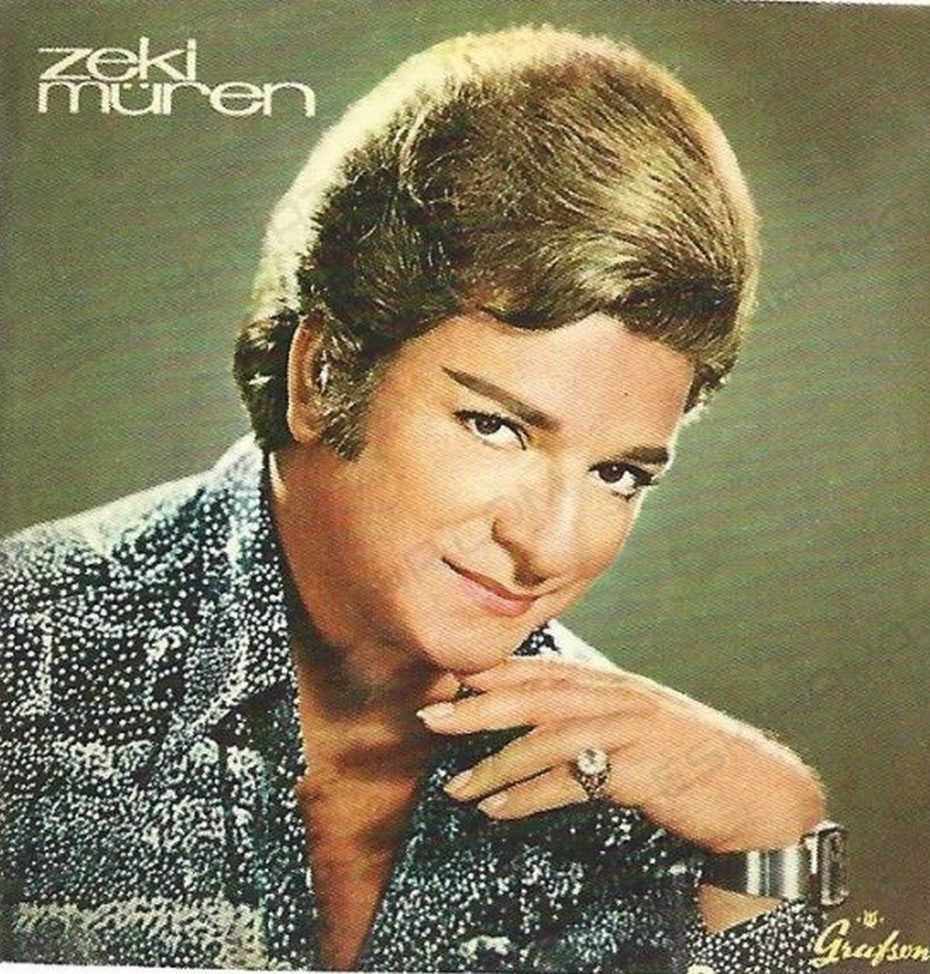

Of course, Müren’s glitzy persona took time to grow, and early photos show a sheepish boy with a mousy pompadour in lieu of the platinum-haired man we remember today. “His father was a lumber merchant,” says Bodrum’s Cultural Centre, and his family didn’t understand his artistic hopes. He was heartbroken when, one day, he came home from school to find his mother fanning herself with one of his drawings.

Müren’s artwork

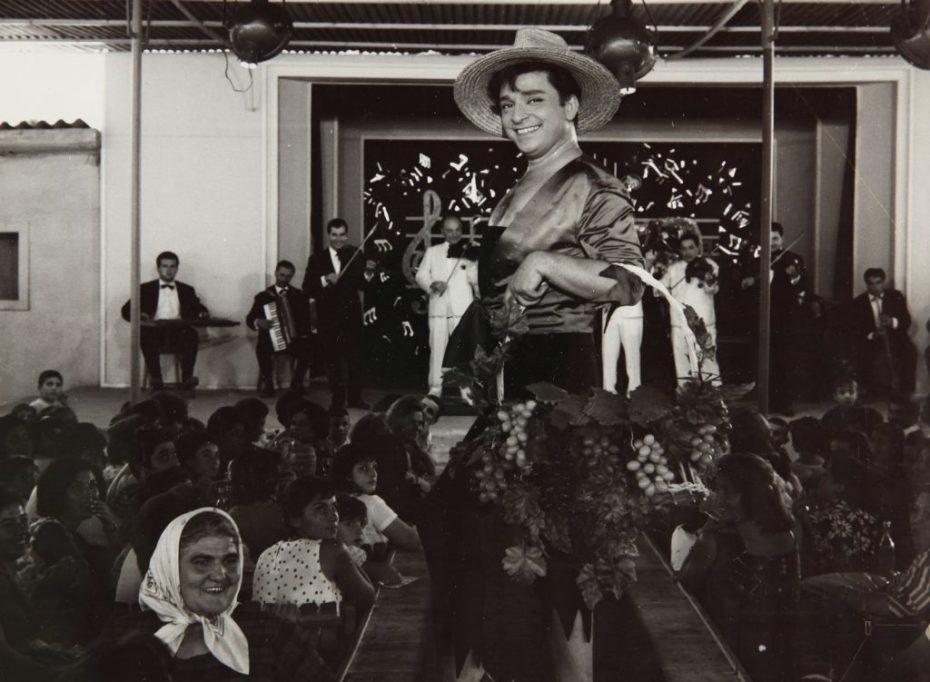

“In his university years, he joined Istanbul Radio as a regular singer,” says the Centre, “In 1951, his first concert brought him a great fame. One of his songs, Manolyam, won the Gold Record .” He jumped into a wholesome, Mickey Rooney-type persona for various modeling, acting, and singing gigs, and all the while his true colours (and sexual orientation) sat under the radar…

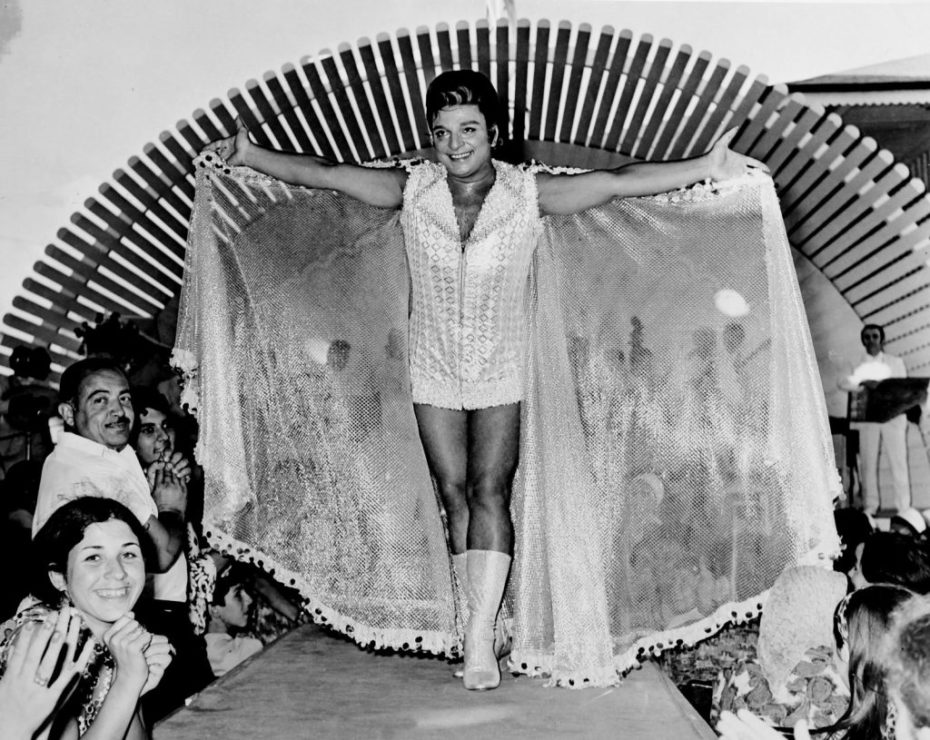

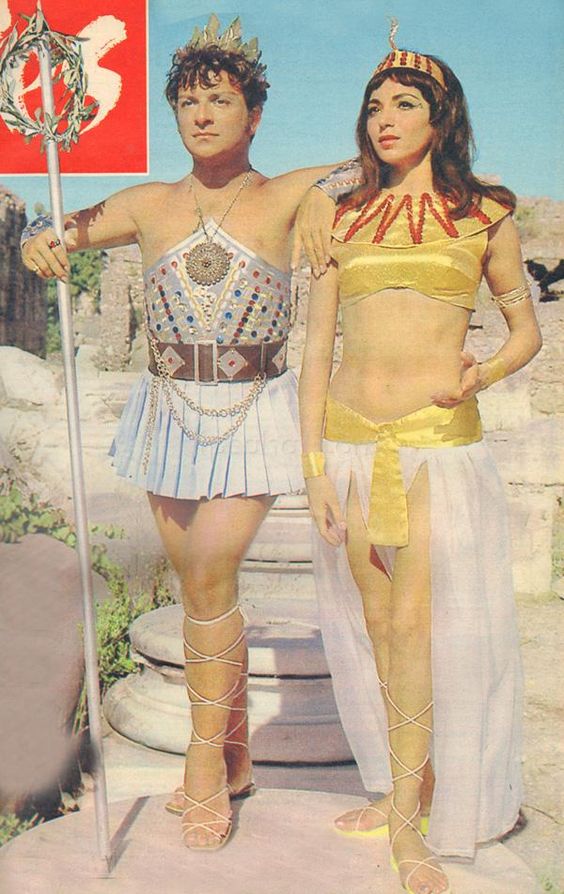

Although, one glance at his editorial work, and it’s clear he was destined for bigger (and sparklier) things:

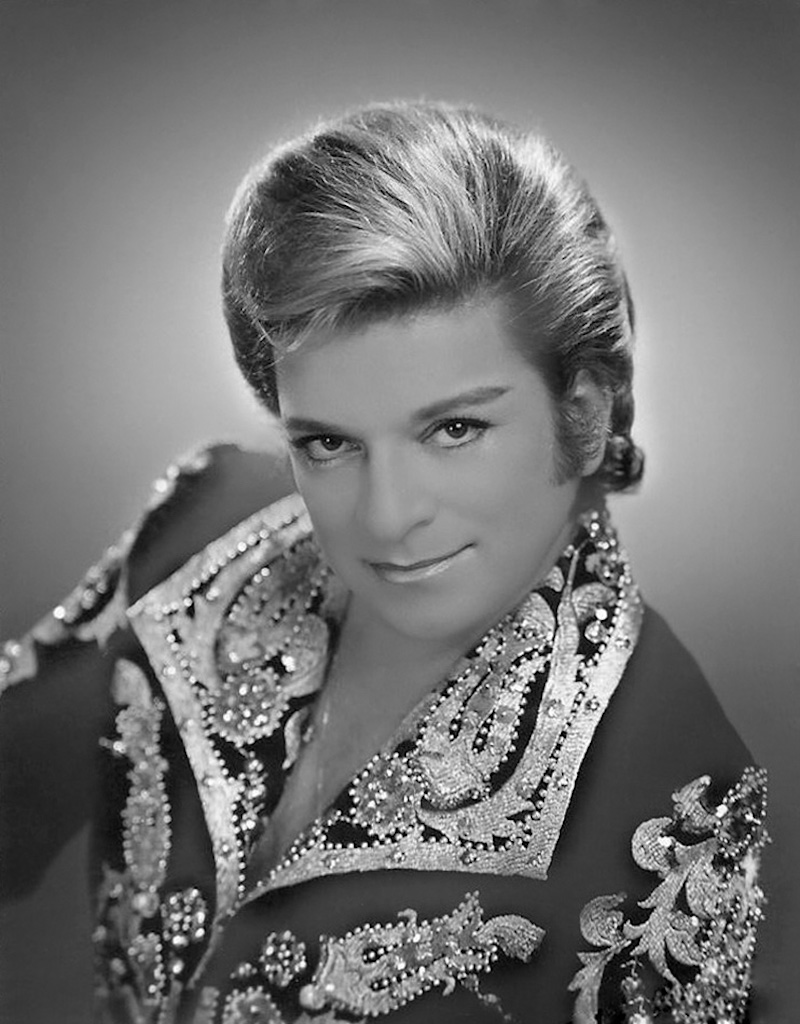

That Müren was able to develop such a flamboyant persona in 1950s Turkey, becoming a queer and conservative icon, is pretty baffling. It was largely thanks to his mastery of Turkish classical music, said the BBC, “which has its roots in the court music of the Ottoman Empire.”

“My parents used to tell me they’d put on some Zeki Müren to ‘get in the mood’,” laughs a young Turkish fan named Hakan Özyilmaz, “Everyone knew he was gay, but no one said anything.”

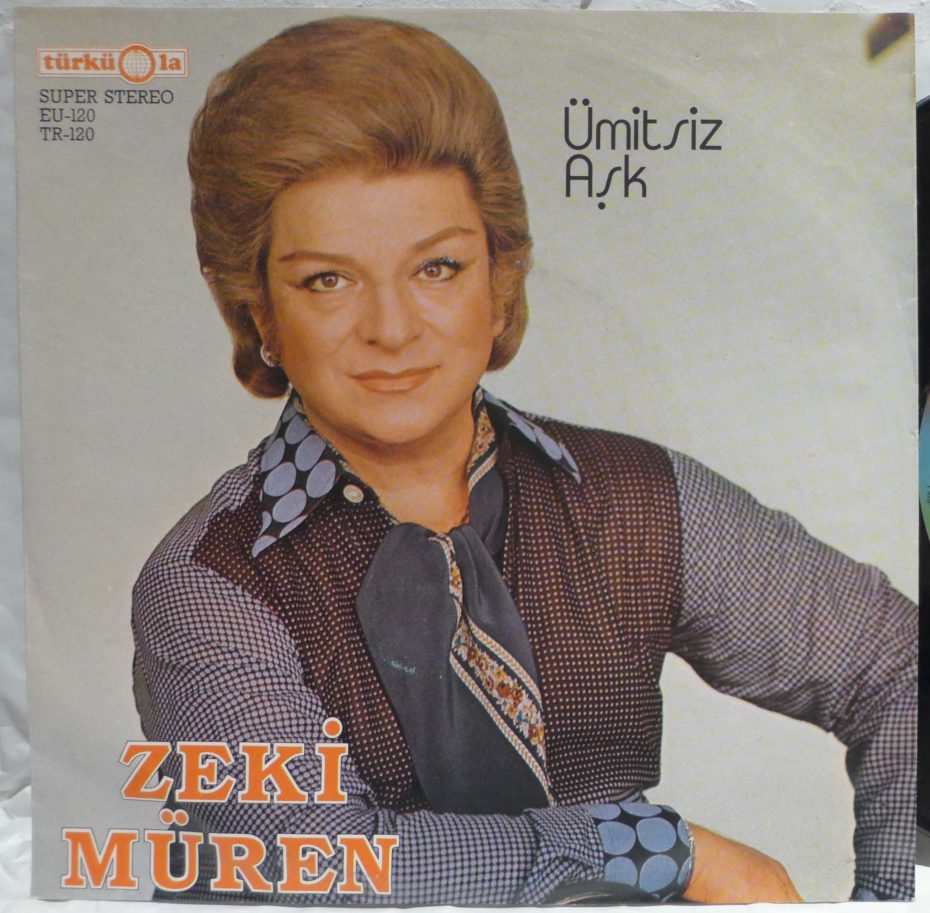

Over the course of his life, Müren composed hundreds of songs (many of which were censored on television), as well as design a seemingly endless array of costumes. “He would even give his costumes affectionate names, such as Mountain Flower, Moon Prince or The Lover of Dr Zhivago,” said the BBC, “he wore one named Veil of Fortune, a glittery super-minidress accompanied by a shiny cape.”

That’s not to say there weren’t some cruel bumps in the road to success. An angry mob once stormed his concert, waiting to beat him with sticks. Instead, he struck a deal with them; “Just have a listen to my songs,” he said, “If you still want to beat me up, you can.” Allegedly, they like what they heard, and the sticks were dropped.

Here’s a performance of his from 1970 (skip to the 1:17 mark to actually hear him start singing)…

The final years of his life were plagued with health complications, and he took a 10-year haitus from the stage before making one final appearance during an awards show in 1996. “I paid my price with my heart, unfortunately,” he said, “my heart is tired and said that this event comes from the stress of the scene that lasts for 25 years; doctors. And I said goodbye to the stage…I gave my heart. I bought a lot but I gave it my heart.”

He spoke the words clutching the stage’s microphone — the same he’d used on his first TV appearance — ready to accept an award for his work, when he fell dead from a heart attack. The country went into a state of shock, with over 90,000 people turning out for his funeral.

To this day, there’s a gaping, Zeki Müren-shaped hole that time can’t seem to heal. At least, that’s one of the reasons for the Zeki Müren Hotline, which was founded in 2016 by filmmaker Beyza Boyacioglu. It “collects everyday people’s memories and stories through a simple telephone hotline,” she says about the experience, which begins as soon as you dial the number, and wait to hear Müren’s recorded, signature cooing (“Hellooo, this is Zeki Müren.”) before callers share their love for the artist.

“When I was four we had many of your albums,” says one 30-year-old woman, “I used to cry and cry because I wished my mother was Zeki Müren. They used to make fun of me. You died when I was in high school. Today I sometimes cry when listening to your songs. I love you very much.”

At present, almost a thousand calls have been made in his memory, and compiled in a documentary about the artist. The hotline has given Müren the fresh, global platform he always deserved, at a time when his story is more relevant than ever.

So what are you waiting for? Call up Zeki for yourself at 0212-988-0208, and learn more about the film here.